![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

Organisations often act in ways that seem irrational or contrary to their interests. In particular they sometimes fail to attend properly to hazards that lead predictably to disaster. A case in point is the petroleum company, BP, which has suffered catastrophic accidents twice in recent years: the Texas City refinery explosion in 2005, and the oil well blowout in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010. These events took a huge human toll: a total of 26 people died, hundreds were injured and countless friends and relatives were bereaved. But it is the economic cost which is relevant here. The Texas City explosion cost the company billions and significantly affected its share price, although it did not threaten the existence of the company. The oil well blowout cost BP even more dearly – in the order of $40 billion. Given that the market value of BP at the time was about $120 billion, this was a body blow that came close to destroying the company. Three years later the share price remained 25% below where it was at the time of the blowout. Given the scale of these economic consequences, BP’s failure to devote more resources to controlling these hazards looks to be economically irrational, at least in hindsight.

Such irrationalities make a lot more sense, however, when we recognise that organisations themselves don’t act – individuals within them do. Behaviour that seems irrational from an organisational point of view may be far more intelligible when seen from the point of view of individual actors. Their failure to spend money on the prevention of major accidents may indeed be quite rational for them. Major accidents are rare, and underinvestment can continue for years without giving rise to disaster. On the other hand, managers are judged on their annual performance, especially with respect to profit and loss. Consequently, spending money on the prevention of major accident events is not necessarily in their short-term interest. On the contrary, cutting expenditure on maintenance, supervision and training may enhance short-term profits, while inexorably increasing the risk of disaster in the longer term. Moreover, business unit leaders tend to think in the short term because they may only be in a particular management position for a couple of years before moving on. They may thus be long gone before the results of their cost-cutting decisions become apparent. At least one commentator, Bergin, has seen this as a root cause of the Texas City explosion: “Managers did not act to prevent Texas City (he says) because every incentive and potential penalty they faced told them not to.”1 The same could be said for the Gulf of Mexico blowout.2

In order to fully understand the way the incentive system worked to distract attention from major hazards at Texas City, and for that matter in the Gulf of Mexico, we need to develop the distinction between personal and process safety. This distinction was highlighted in all of the reports following the Texas City accident, but was given greatest prominence in the Baker Report, which expressed it as follows:

Personal or occupational safety hazards give rise to incidents – such as slips, falls, and vehicle accidents – that primarily affect one individual worker for each occurrence. Process safety hazards give rise to major accidents involving the release of potentially dangerous materials, the release of energy (such as fires and explosions), or both. Process safety incidents can have catastrophic effects and can result in multiple injuries and fatalities, as well as substantial economic, property, and environmental damage. Process safety in a refinery involves the prevention of leaks, spills, equipment malfunctions, over-pressures, excessive temperatures, corrosion, metal fatigue, and other similar conditions.3

In some contexts, process safety hazards are referred to as major hazards or major accident hazards.4 These latter terms are more general: they apply to rail and air transport and underground mining, all of which can experience catastrophic accidents, although they cannot be described as process industries.

Since personal safety and process safety are concerned with different kinds of hazards, it is logically possible to focus on one type of hazard and not the other. This was the essence of the problem at Texas City and in the Gulf of Mexico accident: the focus was on personal safety hazards, not process safety hazards. This was not a conscious choice. Many managers did not understand the distinction or, if they did, they assumed that attention to personal safety hazards would automatically ensure that attention was given to process safety.

Nor was this a personal failing on the part of individuals – it was the result of a deep-seated and widespread organisational failure. Safety is commonly measured using workforce injury statistics (e.g. lost-time injuries, recordable injuries, first aids). A low injury rate is arguably evidence that conventional occupational hazards are being well managed (to be discussed later), but such statistics imply nothing about how well process hazards are being managed. The problem is that catastrophic process incidents are by their nature rare, and even where process hazards are poorly managed, an installation may go for years without the sort of process safety incident that gives rise to multiple fatalities. So, if an organisation is seeking to drive down its injury rate, it will naturally focus on the hazards that are contributing to that rate on an annual basis. These may be vehicle hazards, working at heights, trip hazards and so on. The stronger this focus, the more likely it is that the organisation will become complacent with respect to major hazards, precisely because they do not contribute to the injury rate on an annual basis.

There is one major hazard industry that has not made this mistake – the airline industry. For the airline industry, major hazard risk refers to the risk of aircraft loss. No airline assumes that having good personal injury statistics implies anything about how well aircraft safety is being managed. The reason, no doubt, is that there is just too much at stake. When a passenger airliner crashes, hundreds of people are killed. The financial and reputational costs to the airline are enormous and there is the real risk that passenger boycotts might threaten the very existence of the business. Moreover, unlike those killed in industrial accidents, many of the victims of airliner crashes are likely to have been influential and/or to have influential relatives, which tends to magnify the costs and other consequences for the airline. For all these reasons, airlines have developed distinctive ways of managing aircraft safety and would never make the mistake of using workforce injury statistics as a measure of aircraft safety. It is just as senseless in process industries as it is in the airline industry to assume that injury statistics tell us anything about how well major hazards are being managed.

Consider now how BP’s incentive system worked at Texas City, and in the Gulf of Mexico. Bonuses were paid to people at all levels of the company largely on the basis of productivity and cost minimisation. There was a safety component, but this was largely determined by injury statistics. There was nothing in the bonus structure to focus attention on how well major hazard risk was being managed. Texas City experienced numerous dangerous gas releases each year. This could easily have been treated as an indicator of how well process safety was being managed and included in bonus calculations. But it wasn’t. It was this that led Bergin to conclude that “Managers did not act to prevent Texas City because every incentive and potential penalty they faced told them not to.”

This problem was identified in various reports following the Texas City accident. The Baker panel report made the following recommendations:5

A significant proportion of total compensation of refining line managers and supervisors [should be] contingent on satisfactorily meeting process safety performance indicators and goals …

A significant proportion of the variable pay plan for non-managerial workers … [should be] contingent on satisfactorily meeting process safety objectives.

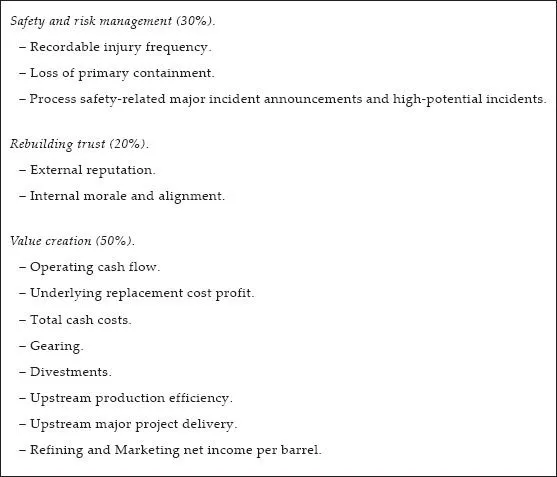

These seem like eminently sensible suggestions. And they have been very influential. In recent years many companies in process industries have recognised that the criticisms levelled at BP applied to them as well, and various companies, including BP, now include some indicators of process safety in their bonus structures. The basis on which BP paid its annual bonus to its most senior executives in 2012 is presented in Figure 1.1. The value placed on rebuilding trust is evidently a response to the Gulf of Mexico disaster. Other than that, the main point to note at this stage is the safety component which, at 30%, is the highest we have seen. Total recordable injury frequency is a measure of personal safety, while loss of containment events – leaks and spills – is a measure of process safety. This is a bonus scheme that, if anything, gives greater weight to process safety than to personal safety. In principle, this will focus company attention on major hazard and environmental risks far more effectively than previously.

Figure 1.1 Bonus structure for top BP executives, 20126

A more cautious approach

The preceding account ends on an optimistic note. But before drawing any firm conclusions about these new developments, there are a number of questions we need to ask about whether incentive systems really function as intended. First and perhaps most fundamentally, are we primarily driven by financial incentives, or are we motivated by other kinds of rewards, such as job satisfaction and positive feedback from supervisors, that make financial rewards largely irrelevant? Second, assuming that there are circumstances in which we respond to financial rewards, do these rewards motivate the intended behaviour or do they simply encourage people to manipulate the measures (“game the system” in contemporary jargon) in such a way as to gain the desired reward without achieving the intended ends? In short, do they have unintended and perverse consequences that undermine them? Third, are the indicators that are being used to measure catastrophic risk the right ones? It is incumbent on those who advocate incentive systems to consider these questions carefully and to examine critically the new incentive systems that companies are developing to identify their strengths and weaknesses. This book starts, therefore, with general considerations about human motivation and incentive systems and moves ultimately to an empirical study of particular incentive arrangements in a number of companies operating in industries where there is the potential for disaster. These arrangements turn out to be surprisingly complex. Accordingly, a significant part of the book is devoted to examining the logic of these schemes and the impact they might be expected to have.

Our empirical study is based on 11 companies operating in hazardous industries. We examined documents provided by these companies and carried out multiple interviews with the senior people in each company most able to describe how their systems worked. The companies were drawn from the oil and gas, petrochemical and mining industries. Clearly there are other industries with the potential for catastrophe, for example, aviation, rail, nuclear power and even the finance industry, as the global financial crisis demonstrated. Our study is therefore limited to a subset of industries in which catastrophe can occur. The companies were mostly large multinational concerns, with headquarters in several different countries. A couple of the companies selected were smaller, operating in a single country. Most were publicly listed companies, although a few were wholly owned subsidiaries of larger, multinational operations. Another limitation of the study is that we have no data on national oil companies (NOCs), which are influential players on the world stage. The incentive systems that operate in NOCs may be systematically different from those identified here and a follow-up study on this subset of major hazard firms would be of considerable interest. The companies selected are not a statistically random sample; rather, the sample is purposive: designed to cover the range of possibilities in the industries concerned. Studying these firms therefore gives us a picture of the problems and possible solutions. Finally, we interviewed a number of senior managers in a subset of these companies about just how they responded to these incentive schemes.7

Outline of book

The book falls naturally into two parts. The first part, consisting of Chapters 2 and 3, sets out the issues in more detail, while the second part, consisting of Chapters 4, 5, 6 and 7 sets out our empirical findings in relation to some of these issues.

In Chapter 2 we discuss some research findings on the impact of incentives on human behaviour and their relevance in the present context. The chapter highlights the work of Daniel Pink who argues that in this matter there is “a mismatch between what science knows and what business does”.8 In particular, he says, science knows that people are motivated more by intrinsic rewards (e.g. job satisfaction) than by extrinsic rewards (e.g. money), yet business continues to pay financial bonuses as if economic motivations were all that mattered. Pink has been very influential in his advocacy, to such an extent that at least one company we have studied has decided to abandon aspects of its bonus system and rely on ‘conversations’ initiated by the CEO and propagated down through the organisation. The expectation is that these conversations will engage people’s intrinsic motivations and that this will ensure alignment with company objectives more effectively than paying bonuses. Pink’s argument is a serious challenge to the line of argument we developed earlier in relation to BP and in particular calls into question the Baker panel recommendation that companies should aim to include process safety in their bonus arrangements.

However, as we shall see, the findings on which Pink relies do not apply in any straightforward way to the issue of company bonuses. We can begin to get a glimpse of the difficulty by remembering that bonuses are often paid in the context of performance evaluation. This means that the size of the bonus reflects the opinion of the evaluator on how well the person has performed. In this context a large bonus amounts to a congratulatory handshake while a small bonus is inevitably read as a criticism. In this way the bonus becomes a psychological reward as well as an economic one. Much of the research on the impact of monetary rewards pays no attention to the psychological component of bonuses as actually paid in the corporate world, making the research of dubious relevance, if not totally irrelevant, in the present context.

An important aspect of this question of the impact of incentives is the issue of unintended or perverse consequences. Chapter 2 deals with this as well. It begins by noting that this problem besets policy makers in many fields, such as health care and education. When it comes to safety, one of the unintended consequences of paying bonuses for low injury rates has been the underreporting of incidents. Underreporting may stem directly from pressure not to report. It may also result from sophisticated classification strategies that ensure that injuries do not count as injuries for the purpose of bonus calculations. The problem is so great that various authorities have argued that bonuses should never be paid...