![]()

Chapter 1: Too young to die

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

(Dylan Thomas, 1914–1953)

Nothing causes more public anger than when young people’s lives are cut short by carelessness or negligence.

The Marine cadets marching disaster, Chatham, England, 1951

I shall always remember the first civilian disaster that came close to me as a nine-year-old, growing up in the Medway Towns. I had often cycled down Dock Road to Chatham Naval Dockyard and was familiar with the site of the horrific road accident that occurred on the evening of 4 December 1951.

What happened?

A troop of 52 young people aged from 10 to 13, all members of the Royal Marines Volunteer Cadet Corps, led by a regular Royal Marines officer, were marching three abreast from Gillingham down Dock Road towards Chatham Dockyard where they were to attend a boxing tournament. They never made it. A local service double-decker bus ran them down in the dark, killing 24 and injuring 18. The driver realised something was wrong and pulled up some yards down the road, still unaware of what he had done.

Why?

The street lighting was very dim. The troop was marching on the left-hand side of the road with their backs towards following traffic, all wearing smart dark blue uniforms, but with no lights. It was dark and as they passed an even darker section where the street lamp was out, in spite of their wearing white belts and lanyards, the bus driver failed to pick out the marchers.

He had worked for the bus company for 40 years, 25 as a driver. The speed of the bus was later the subject of some dispute – he claimed only 15–20 mph but the officer (who had seen him coming and moved the column in towards the kerb) estimated much more. He was driving on side lights only, as was common practice at the time and not against the law, though in those conditions it would seem sensible to have used headlights too.

What happened next?

Investigations tended to be finished a lot faster than today in those immediate post-war years. An inquest was held on 14 December and the jury returned a verdict of ‘accidental death’. The coroner found that neither the driver nor the officer leading the troop had been negligent, but the driver was charged by the police with dangerous driving, convicted and banned for three years and fined £20. The bus company accepted liability and paid the parents of the dead and injured compensation totalling £10,000.

The graves and memorial to the victims of the Chatham bus crash in Woodlands Cemetery, Gillingham.

© Jason Ross/www.historicmedwayco.uk.

Lessons

It was obvious that the street lighting in Dock Road was inadequate. As a direct consequence of the tragedy, local councils embarked on a programme to improve street lighting throughout the Medway Towns. From then on, the armed services would always display a red light at the rear of any columns marching anywhere at night.

Aberfan coal tip disaster, South Wales, 1966

For 50 years, millions of tons of colliery waste from Merthyr Vale coal mine had been accumulating in several massive tips on the mountainside above the village of Aberfan in Wales. This was an accident waiting to happen.

What happened and why?

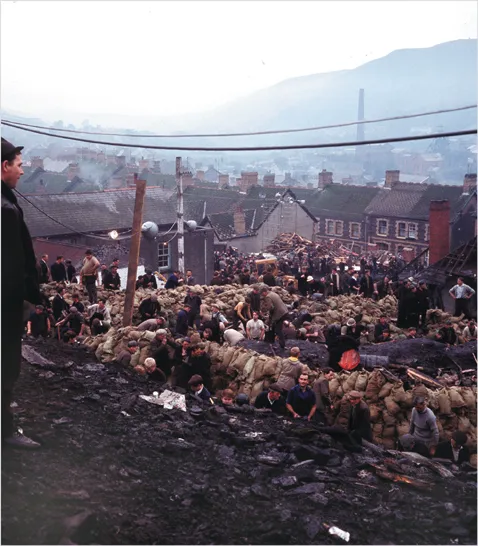

On Friday 21 October 1966, at 9.15 in the morning, an unbelievably horrific catastrophe occurred. A roaring avalanche of black slurry, trees, boulders and muck surged down from a man-made mountain of colliery waste, engulfing the junior school, part of the separate senior school, a farmhouse and 20 houses.

A deathly silence then descended, until miners hurrying from their shift change arrived and began desperately searching for survivors in the rubble. Hardly anyone was found alive. The junior school had been totally wrecked. A hundred and forty-four people, including 116 children between the ages of seven and 10, perished under the muck, among them the children and grandchildren of miners working at Merthyr Vale, tragically the very source of the destruction. Five teachers also died. Only a few minutes earlier the children had been singing ‘All things bright and beautiful’ in assembly.

That October, heavy rain had been falling for several days, saturating the spoil until it became completely waterlogged and unstable. Its collapse was inevitable. Ordnance Survey maps showed that tip number 7 was lying above a stream. Some previous collapses were known to have occurred but without serious consequences, which may well have contributed to the complacent attitude displayed by the colliery’s management towards the safety of the tip, and their failure to foresee and prevent the tragic consequences of the slide that occurred on 21 October.

What happened next?

The mine and tip were managed by the National Coal Board (NCB), all the coal mines in Great Britain having been taken into state ownership by the postwar Labour government. There might have been some expectation that safety would have been high on the NCB’s agenda, yet surprisingly the response of the Chairman of the NCB was to claim that nothing could have been done to prevent the accident.

Politically, it was essential for something to be seen to be done, and quickly. This was one of the first major disasters to be seen on national television and the general public were appalled by the tragedy.

A Tribunal of Inquiry was immediately set up under Lord Justice Edmund Davies, who heard evidence for several months. Men working on the tip said they had seen the slide begin but were unable to give any warning. A telephone line was out of order (though even had it been working, it probably would not have been much help on the day, so rapid was the collapse).

While the inquiry found the immediate cause to have been the saturation of the tip by water, which allowed fine materials to begin to flow down the mountainside, undermining and taking everything else with it, the underlying causes were found to be “ignorance, ineptitude and a failure of communication”, for which the NCB was held to blame.

The NCB was required to pay £500 compensation to the families for every child lost in the disaster but no NCB employee was disciplined.

As is so often the case, an appalled and generous British public donated an enormous sum, about £20 million in today’s money, to the disaster fund, indicative of their great shock at this tragic event and deep sympathy with the families. However, some of this publicly donated money was controversially used to make the tip safe, saving the NCB considerable money. Later, in 1997 the new Labour government repaid the fund some compensation, and in 2007 the Welsh Assembly donated another £2 million.

Rescuers search the slag heap that engulfed Aberfan, 21 October 1966.

Popperfoto/Getty Images

Lessons

There had been a glaring failure to assess risk. No account had been taken of the evidence of previous slips, and geographical information on local Ordnance Survey maps about the presence of the stream beneath the tip had been ignored by a complacent management.

The safety of tips had not been covered by the Mines and Quarries Act 1954 which applied at the time. However, one positive result from this shameful calamity was the Mines and Quarries (Tips) Act 1969, which required regular inspection and maintenance of tips associated with mines and quarries. The regulatory authority, HM Mines Inspectorate (then part of the Department of Energy), began recruiting civil engineering surveyors to monitor how well the NCB complied with its duties under the new Act.

No tip disasters have since occurred in British coalfields. In 1970 Lord Robens, Chairman of the National Coal Board, went on to chair a committee that recommended sweeping changes in the regulation of health and safety at work.

Lyme Bay canoeing tragedy, Dorset, England, 1993

It doesn’t take much negligence to cause a disaster. In 1993 four young people learning to canoe against the beautiful backdrop of the Dorset coast lost their lives due to a company’s shocking neglect of their safety.

What happened?

An ‘adventure activity’ business, OLL Ltd, offered canoeing courses at a centre at Lyme Bay. On 22 March 1993 a school party was on the second day of a week’s course. They were complete beginners, with only one day’s previous experience in a pool in St Albans. A small group of young people, each in a kayak, paddled away from Town Beach, Lyme Regis, accompanied by two instructors. Their short voyage across the bay to Charmouth was expected to take only two hours.

But the teenagers were ill equipped for the worsening sea conditions. By the time they were a little way offshore the waves had become very threatening. One canoe soon capsized and while rescue attempts were being made by the instructors, other canoes were being swamped and swept away by the tide.

Why?

Before this tragic incident occurred, two instructors had complained to the managing director about the centre’s poor safety standards and inadequate safety equipment, including the lack of flares. The instructors felt so strongly about it they resigned, saying: “We think you should take a careful look at your standards of safety, otherwise you may find yourself trying to explain why someone’s son or daughter is not coming home.”

He ignored their warnings.

What happened next?

The alarm was raised when the party failed to arrive at Charmouth but precious time was wasted by the centre’s staff in a fruitless search before the Coastguard was alerted. A helicopter search began when a fishing boat spotted an empty canoe a couple of miles away from Lyme Bay and radioed the Coastguard. By then nearly four hours had elapsed, and while the search had continued close to shore, the survivors had drifted eight miles out to sea.

Four of the youngsters, a teacher and the two instructors managed for a while to cling to a sole remaining canoe until it, too, sank, and they were eventually found and saved, suffering from hypothermia and exhaustion. But by then four teenagers had already drowned, their life jackets waterlogged and unable to support them.

The company was prosecuted for corporate manslaughter and its managing director for manslaughter. He had been warned of the danger and was unable to explain why he had taken no action. The company was convicted and fined; the director was convicted and jailed for three years.

Lessons

In the wake of this tragedy there was strong public feeling that adventure activities needed to be properly regulated and licensed. The Health and Safety at Work etc Act clearly applied and included licensing powers. But the Health and Safety Commission, the obvious authority, was reluctant to take on the licensing of these businesses, arguing that licensing should be reserved for major hazards such as nuclear power stations and explosives factories, not for recreational activities. The government of the day sidestepped their objection and bowed to public pressure by establishing a ...