![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

Berry Billingsley and Manzoorul Abedin

Most people wonder about the so-called “Big Questions” – such as how did the universe get here? – at various points in their lives and for many reasons. Commonly at such times thoughts turn to what science and religion seem to say.

Research over the years has consistently shown that a majority of children perceive that science and religion conflict. The LASAR (Learning about Science and Religion) project was established in 2009 to find out more about children’s ideas and also to look at how questions and themes bridging science and religion are managed in schools.

Stereotypes, such as that science and religion are mutually exclusive, that someone with a religious faith is not likely to become a scientist and that scientists are typically atheists, are frequently articulated in some parts of the media, popular TV shows and jokes. The impact of these stereotypes each time they recur in popular culture on children’s developing thinking is difficult to estimate but it has been established via large-scale surveys that, by the end of primary school, a significant proportion of children aged 10 already say that science and religion are mutually exclusive. Survey findings (n = 712) with children in this age group found that about one-third (34%) agreed with the statement “Science and religion disagree on so many things that they cannot both be true”, while just under one-third (27%) of the cohort disagreed. Fewer than one in five (16%) of children agreed that “Science and religion work together like friends” while almost half (46%) of those surveyed disagreed (Billingsley & Abedin, 2016). But while the media do influence children’s thinking, it is the way in which schools respond that decides whether these stereotypes can either persist and spread or fail to get a foothold.

The findings from LASAR’s research have highlighted that not only in secondary but also in primary schools, teachers tend to present and discuss questions via compart-mentalised curriculum boxes. While immersing students in the questions, methods and norms of thought of one discipline at a time is an essential and important aspect of education, there are many topics and questions that are missed out by this approach. Further, the research concluded, if teachers don’t create opportunities for questions that go beyond subject silos, children pick up the message that these kinds of questions are unwanted.

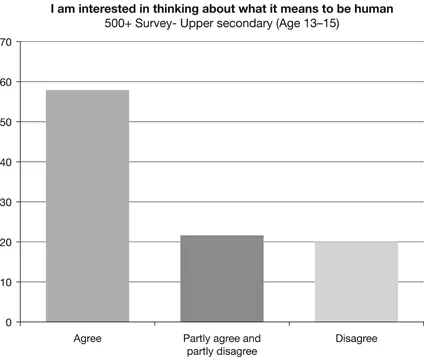

Even so, children’s curiosity and enthusiasm for exploring the so-called Big Questions, such as what does it mean to be human and how did the universe get here are consistently high for all ages (see Figure 1.1).

While enthusiasm to think about the origins of life and the universe remains high across the age groups, studies with secondary school students indicate that in this age group, levels of belief in creation by God fall. A survey of 2613 secondary students by LASAR (Billingsley, 2017) found that just over one-fifth (21%) agreed with the statement “I believe that God created the universe”, while 45% disagreed. The proportion of students in each year group who believe that God created the universe decreases for children in older age groups (from about a quarter – 26% in Year 7 down to 17% in Year 11). The percentages of students who perceive science and religion to conflict on the questions of why life and the universe exist rise from younger to older age groups. Comparing students in Year 7 through to Year 11, for the origins of the universe the level of disagreement with the idea that science and religion fit together rises from 45% to 60% and for the statement relating to how life began, the percentages and changes in percentages are very similar. In the light of the conflict that many students perceive to exist, some choose sides depending on where they feel they belong – as one 14-year-old girl explained: “I think God created the universe, but if you don’t have a religion, then you might think that it was the Big Bang. Because I have a religion, I think it was God who created it.” Another group of children say they are confused and within this group some say they hold onto both, even though they see them as competing. While filling in our survey, one student noted that she had struggled with many of the questions because “There’s the science part of me that says ‘no, it’s the big bang’, and then there’s the religious part of me that said ‘it was God’, so it was quite confusing.” A significant proportion of children say they take the side of science, saying “it has more evidence” or “it is certain”.

Interviews with primary and secondary school students show that there are common challenges for both age groups. One of these challenges is that most children have no one who seems like the right person to ask about these types of questions. Very few, in particular, have someone they can talk to about science and religion at the same time. Comments by children aged 10 who participated in a survey included: “I ask my teacher about science and our reverend about religion.” Children perceive the people they know to be committed either to science or to religion, such as: “Our dean believes that God created the beginning of the universe … [the other children in my class] would think that maybe the Big Bang created it and not God” (10-year-old boy). For secondary school students, the scarcity of opportunities to learn about how science and religion relate is reinforced by the allocation of science and religious education to different subject specialists. The RE teacher is generally perceived by children not to be a science specialist and as one student explained: “No one really asks the science questions because you’d really more ask your science teacher about that instead of asking your RE teacher.” At the same time children perceived that it would be “off topic” and/or culturally sensitive to ask questions that touch on religion in their science lessons. One student explained: “We don’t ask science teachers questions any more at the moment, because we don’t think that they’d answer them … they won’t answer that because it’s not on their topic” (Billingsley & Chappell, 2016; Billingsley, Nassaji & Abedin, 2016; Billingsley, Taber, Riga & Newdick, 2016).

What all of this means is that children in school struggle to find opportunities to ask questions and talk about big questions that bridge science and religion. This is unfortunate because exploring these questions can help young people to form a deeper understanding of both science and religion and encourage them to become more thoughtful and questioning about what they learn in school. The implications of this conflict for teaching and learning have been reported in the United States (Smith, 2010), the United Kingdom (Fulljames, Gibson & Francis, 1991; Taber, Billingsley, Riga & Newdick, 2011), Australia (Billingsley & Fraser, in press) and other places around the world (Deniz, Donnelly & Yilmaz, 2008; Ha, Haury & Nehm, 2012; Hansson & Redfors, 2007). Children’s attitudes to science and to careers in science can be affected by their perceptions of how science relates to their religious beliefs (Esbenshade, 1993). Although the conflict view is widespread, it is not a necessary position. Unless students receive effective teaching, they are unlikely to develop the epistemic insights needed to understand why science and religion are not necessarily competing (Billingsley, Taber, Riga & Newdick, 2016; Reich, 1991). Also, whether or not students have a religious faith, it is important that all students appreciate the diversity of metaphysical stances that can be compatible with science (Hokayem & BouJaoude, 2008). The need for children to have access to positive views of how science and religion relate is therefore becoming a higher priority in schools. This follows a growing appreciation by the public, by church education authorities and by teachers that children need to have effective teaching if they are to appreciate why the conflict view of the relationship between science and faith is not the only position available to them.

Chapters in this book together emphasise the need for children to see the value and significance of questions that do not sit neatly in one subject or another. Primary and secondary students need frameworks and bridges to enable them to move successfully between their subject compartments – and this book provides a number of lesson plans and pedagogic strategies towards that goal. For many decades the practice at almost every level of education has been to teach students about scholarship and knowledge via a compartmentalised system of individual curriculum boxes. The compartments are sustained by subject-specific curriculum documents, examinations, teacher education and – in secondary schools – specialist teacher recruitment and subject specific classrooms (Cloud, 1992; Ratcliffe, 2009). In this way pedagogy can squeeze students’ curiosity and channel their thinking away from creative activities such as identifying good questions to ask and devising ways to address them. Taken together, various chapters in this book provide a cohesive framework to help students make sense of words and ideas such as “evidence” that are referred to in many subjects and modules.

Addressing these Gaps – Where to Start

Children’s perception of science and religion as conflicting depends on many things. It depends in part on what they are hearing from the media, in the playground and at home. If children repeatedly encounter the message that science and religion are mutually exclusive, then, with no reason to suppose otherwise, it seems reasonable to say that most will accept this position unquestioningly as true. But this is not the only factor at work. One of the key steps on the journey towards appreciating why science and religion are not necessarily incompatible is to consider the idea that science and religion are mostly concerned with different types of question. This matters because it explains why they are not necessarily rivals – even when they appear to be discussing the same topic. The idea that different disciplines can work together is not something that children very often consider. In school, the questions that children meet are categorised into different subjects. So in science children look at science questions, in history they look at history questions etc., but children do not often meet a question that is presented as one that could be addressed by more than one of those disciplines. One way to help build up these ideas with children in primary school is to give them a question that has multiple answers so that they can pick out which one or ones may be scientific. You could say to children: “Yesterday, I was sitting at home and suddenly the doorbell rang. Why do you think the doorbell rang?” and then invite them to think of as many answers as they can. Once children have generated a number of suggestions, tell them that the answer you were looking for is that a little clapper struck it several times, vibrated the bell and made a sound.

This answer is likely to be different to the ones the children thought of but is also likely to be compatible with them. It would be compatible for example with: “My friend was at the door.” This activity can be a stimulus for noticing that if a question is to be investigated using science, it means it must be possible to investigate it by making observations of the physical universe. To try another example for themselves, children could generate multiple answers to the question: “Why did the book fall off the table?” More able children might be able to explain what type of answer each one is and whether it is testable scientifically. In other words, does their explanation describe the “the physical processes that made it happen” or “a human story which fills in a bigger picture”? The point is that both types of explanation can be true at the same time – and, indeed, we might find it useful to have both together. This kind of thinking can be described as building up an answer that has many layers of explanation. Each layer is another discipline (scientific, historical). Children could be asked, for example, to research an answer that has several layers of explanation to address the question. “Why did the Titanic sink?” In the chapters that follow, there are examples of questions that bridge science and religion and also examples of questions that bridge science and other disciplines.

Does it Make a Difference?

In this book, there are teaching ideas for a series of topics on which science and religion both seem to have something to say. These teaching ideas have been developed and refined over many years through workshops with different age groups. Many of the workshops can be adapted for use either in primary or secondary, but, in this book, they are ordered from upper primary to upper secondary. The impact of sharing these teaching points with children can be dramatic. LASAR works with primary and secondary schools to provide children with an off-timetable day with three workshops. Students complete a survey at the beginning and end of the day. Table 1.1 shows “before” and “after” data for primary children, and the impact of the workshops is clearly visible.

■ Table 1.1

| | Agree | Neither Disagr agree nor | Disagree |

|

| Many scientists believe in God (or a Greater Being) | Pre-event | 31 | 41 | 23 |

| Post-event | 66 | 27 | 5 |

| Science and religion work together like friends | Pre-event | 16 | 33 | 49 |

| Post-event | 41 | 35 | 21 |

| The scientific view is that God does not exist | Pre-event | 45 | 33 | 18 |

| Post-event | 26 | 40 | 30 |

The popularity of sessions run by the LASAR project indicates the value that schools place on giving students opportunities to engage with these questions – however arguably – these opportunities should be embedded into the standard education that all students can access. The key challen...