eBook - ePub

Prehistoric Woodworking

The Analysis and Interpretation of Bronze and Iron Age Toolmakers

- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Rob Sands explores the evidence left by the use of axes on wooden beams and tools found in waterlogged archaeological sites dating over 2000 years old. A toolmark can not only inform the archaeologist about the implement used, but also provides evidence of building and artifact construction methods and labor patterns. Examples come from the author's work at Oakbank Crannog in Scotland. The volume examines the methods of recording, techniques of analysis and implications of this unusual form of evidence.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Prehistoric Woodworking by Rob Sands in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

The Potential of Toolmark Signatures

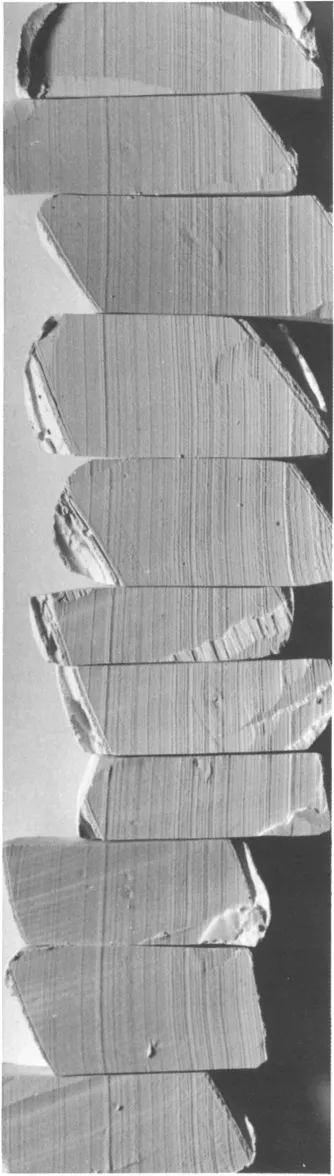

Toolmark studies have been emotively likened to the detective in search of : ‘le tour de main de l’assassin’ (Noel and Bocquet 1987 p.88). There is a degree of truth in this simile; when a tool is used on a piece of wood it leaves a mark and if the tool used has any form of damage in its edge then this too will be recorded on the surface of the wood. Damage in the edge of the tool will be registered as a series of ridges or grooves running down the long axis of the toolmark or facet (Fig. 1). Each ridge or groove in the pattern can be shown to correspond to: ‘an irregularity on the blade, perhaps a chip or bending of metal’ (Coles and Orme 1978a p.79). Coles and Orme described the pattern observed as a ‘signature’ as it could be considered to be unique to a particular tool. These features have also been referred to as ‘fingerprints’ (Orme and Coles 1983 p.25) but as fingerprints are themselves a focus of archaeological examination (Åström and Eriksson 1980) the term will be avoided in this volume.

Toolmark signatures enable the archaeologist to associate timbers worked by the same tool, although this does not necessarily infer that the same person carried out the work. Crucially, the associations established are anthropogenically formed and produce links between timbers that are independent of the natural tree ring cycles that indicate contemporaneous felling.

It has been commented that identical signatures need not imply exact contemporaneity (Coles and Orme 1985 p.44). A comment such as this arises from the fact that it is difficult to establish how long an axe might retain its signature. Signatures will alter through time as a result of resharpening of, and extra damage to, the edge of the tool. Experimentation is the obvious route into this question but the rate at which tool signatures alter will be dependent on a number of factors that make precise figures difficult to establish. There are a considerable number of variables to take into account when setting up such an experiment. Blade edge hardness, for example, varies from one axe to another and consequently different axes would probably wear, and therefore need resharpening, at different rates. Expertise and fitness will also have a bearing on the rate of resharpening. An unfit or inexperienced person can increase the number of blows required to produce a particular object and also the amount of damage that occurs to a tool. Personal preference may also be a factor, with some workers maintaining a keener edge than others.

While exact rates of edge change are difficult to establish reliably, it is clear from experimental work, using both replica bronze and modern axes, that signatures do alter with resharpening, although not necessarily completely during any single episode. Consequently, it is certainly true to say that links between signatures indicate associations that are: ‘even closer in time than the year or half-year deduced by tree-ring analysis’ (Coles et al. 1988 p.15)

Figure 1 Casts of signatures left by a modern axe.

During episodes of intensive work it is not far fetched to suggest that exact matches between signatures are at most a few hours apart. However, it could be argued that axes may be left unused for a period and consequently matches could be found which represented a longer interval of time. While this is theoretically valid it is clear that the axe is not the type of tool that is set aside for long periods of time without use. The axe would have been regularly used both for general wood collection and in the early stages of timber preparation (Earwood 1993 p.203). It would seem reasonable to say that during later prehistoric times it was very much a multi-purpose and widely used tool. An axe would not just be used for larger tasks its use would also include the production of smaller artefacts. At the site of Fiavé, Italy, for example, a neatly executed wooden bowl is clearly produced largely with the use of a typical Bronze Age axe of the area (Perini 1988 p.74 Figs.15-17).

The context of discovery

Toolmarks on wood can only be studied on sites where the conditions are right for their preservation. Fortunately well-preserved waterlogged material has over the years become an increasing part of archaeological discovery and interpretation (e.g. Coles and Lawson 1987; Purdy 1988; Coles and Coles 1989; Coles 1992). Wetland and underwater sites have been discovered across a broad chronological and geographical range; from American Indian sites, such as Hontoon Island in Florida (Purdy 1988 pp.325–35), to many Bronze and Iron Age sites in Europe, such as Cortaillod-Est, in Switzerland (Arnold 1986) or Biskupin, in Poland (Niewiarowski et al. 1992), through Mesolithic sites, such as Tybrind Vig, in Denmark (Andersen 1987), to Palaeolithic and other sites in Japan (e.g. Matsui 1992; Noshiro et al. 1992). All such sites provide the organic preservation that has, until recently, been so often missing from archaeological investigation.

In Britain and Ireland the discovery of waterlogged material is being given a dramatic boost by the establishment of a number of systematic surveys of wetland environments within which waterlogged sites maybe discovered. The North West Wetland Survey, the Humber Wetlands Project and the Irish Archaeological Wetland Unit are all actively discovering new material and building on techniques established during the Somerset Levels Project. A recent survey of known material within Scotland has also begun to identify the enormous potential for future discovery of significant quantities of organic material (Clarke and Finlayson 1995).

In addition to large-scale surveys, new wooden material continues to be found during normal archaeological investigation. Discoveries along the northeastern bank of the river Thames and its tributaries, for example, have revealed a number of wooden trackways and some other constructions located in Bronze Age contexts (Meddens 1996). Recent accidental finds have also demonstrated that major occupation sites still await discovery. At Shinewater Park near Eastbourne in East Sussex, for example, a large Late Bronze Age site, consisting of a number of platforms and posts, has been discovered during the development of a new parkland area by Eastbourne Borough Council (Woodcock 1995).

The survival of wooden material on such sites provides a useful insight into one of the principal materials used by past societies. Examination of this material enables the manner in which it was used to be more fully assessed and the form of wooden objects and structures to be more completely envisaged.

The discovery of wooden elements of house structures has allowed the detail of past construction techniques to be examined. In addition, this has enabled the finds of tools that conducted the work to be placed into a context that extends beyond the merely typological. At a number of sites the discovery of such material has encouraged experimentation into ancient woodworking techniques and tools. At the Late Bronze Age site of Fiavé, Italy, for example, the conditions have preserved not only a considerable number of domestic wooden objects, within an occupation context, but also detailed information on the construction techniques of the housing (Perini 1984). The discoveries on the site have led to a practical consideration of the manner in which the various tools found actually functioned (Perini 1988 pp.48–9; pp.67–77). Such examinations have been conducted at a number of other wetland sites. The Somerset Levels Project, for example, has conducted regular experimentation, references to which can be found throughout their publications (e.g. Coles and Orme 1985). Similar studies at the Late Bronze Age site of Flag Fen, Peterborough, have also led to a more complete understanding of the nature of the construction (Taylor and Pryor 1990; Pryor 1991 pp.77–81). In these and other areas such research has been extended to full scale reconstruction and exhibition (e.g. Ruoff 1992).

The examination of material from such sites not only allows for the reconstruction of additional elements of material culture, it can also allow for the precise determination of site building, repair and abandonment. The recording of tree rings has allowed for both relative and absolute chronologies to be constructed for numerous sites with wooden material. At the Neolithic site of Charavines, in lake Paladru, France, for example, a detailed relative chronology has been built up. This chronology demonstrated the sequence of construction, alteration and abandonment of a series of houses over a period of sixty years (Bocquet et al. 1987 pp.51–4).

Wooden material from the Late Bronze Age settlement of Cortaillod-Est, Lake Neuchâtel, Switzerland has also enabled a construction chronology to be established and at this site absolute dates have been obtained. The site was begun in 1010BC with sporadic repairs continuing until 965BC at which point the entire settlement was rebuilt closer to the present shoreline (Arnold 1986 p.11). It is clear from illustrations of timbers from Cortaillod-Est that the signatures do survive (e.g. Arnold 1986 p.114 Fig.115). Some interesting patterns might be revealed on these and other sites when the dendrochronological conclusions are combined with those that might be established through signature matches.

A number of other reports on waterlogged sites also illustrate, or make reference to, tool-marks on the surfaces of the timbers found. In many cases these are merely passing references but occasionally more extensive work has been conducted (see Chapter 2). While comments are sometimes limited it is clear there is considerable potential for toolmark survival. Consequently, it is arguable that the recording and study of toolmarks has a much broader application within archaeology. This is especially true of the type of submerged or wetland settlement sites where in situ structural timbers are still present and spatial relationships are sought.

The archaeological potential of signatures

The central role of signature matches is to provide unambiguous evidence of association between worked pieces of wood. While this is at the core of their archaeological usefulness the possible implications of this may not be immediately apparent. Such associations can, potentially, have a bearing on a number of site related issues that can be summarised as follows.

Spatial and chronological aspects of construction

Identifying structural patterns

Signature associations made between in situ timbers may demonstrate a coherent structure amongst otherwise confused material. By plotting the position of timbers produced by particular tools, patterns of otherwise unsuspected structures may emerge.

Identifying building phases

As an extension to the previous point, it can be argued that a particular building phase will involve the use of a set of axes. It will sometimes be possible to associate groups of different axes, using dendrochronology or by observing areas of coherent structure. These suites of axe signatures can then be plotted together as part of a single phase in areas where the structure may be less coherent and the building pattern confused.

Identifying associations between structure and stratigraphy

The most obvious example of this form of connection might be between woodchip deposits and timber uprights which have been worked, or finished off, on site. This could produce important information, particularly on multiphase sites with deep organic stratigraphy. It might be possible, for example, to apply dendrochronological information from larger uprights to chips in layers which would be too small for dendrochronological analysis.

Identifying subtle aspects of production sequences

A single resharpening may not mask the original signature pattern, merely adapt it. Consequently, it is theoretically possible for an order of production to be established for the manufacture of a set of objects. In practice it is easier to demonstrate sequences when new damage is evident, resulting in an extra nick or bend on the blade edge, as the additional damage causes ridges or grooves to be superimposed on an underlying signature pattern.

Aspects of data verification and extension

Providing independent checks on other evidence such as dendrochronology or stratigraphic relationships

When two lines of inquiry are used in unison the interaction between the two can often provide important additional insights. When the two lines of evidence are in agreement then conclusions have added strength and when they disagree problems are highlighted and may be better understood.

Extending information

Many techniques relating to wooden material require extensive laboratory preparation and analysis. It is possible to use signature information on site, sometimes gaining indications of associations almost as soon as the timber has been uncovered and cast. Such associations will, when used with care, allow for information already established for one timber to be quickly transferred to others.

Technological aspects of construction

Reconstructing blade size and shape

Some studies have illustrated and discussed the shape and size of the blade used to conduct certain woodworking activities (e.g. O’Sullivan 1991; Therkorn et al. 1984). If an axe strike has been unsuccessful, the woodworker having had to pull the axe from the wood, a registration of the tool’s edge shape will be left at the bottom of the facet as a jam curve. Occasionally the tools edge will be completely registered but more often than not only parts of the edge will be resolvable. Traditionally reconstructions have been unable to utilise these partial jam curves and full reconstruction is consequently limited. Using signature matches it is possible to join together the different parts of a jam curve from different facets on the same timber to reconstruct complete blade edges.

Reconstructing the functional types of tools used on a site

Improved blade shape recovery increases the archaeologist’s ability to characterise the tool kits used on the site under investigation.

Typological aspects of toolmarks

Fitting toolmarks to known tool styles

The reconstructed blade widths and edge curvatures from a site could be linked to known stylistic types.

Social aspects of construction

Suggesting the number of axes/people involved in the construction of a particular structure

The number of signature groups combined with blade reconstructions will, to some degree, reflect the demography of the workforce involved in the construction.

Suggesting workforce organisation

The distribution of particular signature groups may reflect the organisation of the workforce undertaking the construction. This aspect has to be approached with extreme caution, the positioning of a structural timber is probably several steps down the line from its initial production.

To obtain the most from this type of information it is important that it is recorded promptly and the need for on-site facilities for the handling and conservation of wooden items is clear (see also Chapter 7).

This volume explores the potential of signatures on wooden material from archaeological sites; it suggests methods of recording and analysis, demonstrating the practical application of these techniques and ideas through a case study. The case study is based on worked wooden material from the Late Bronze Age/Early Iron Age site of Oakbank Crannog, Loch Tay, Perthshire, Scotland.

CHAPTER TWO

Past Commenta...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Foreword

- Abstract

- 1 The Potential of Toolmark Signatures

- 2 Past Commentaries on Toolmarks

- 3 Toolmark Recording

- 4 Computer Analysis

- 5 Oakbank Crannog

- 6 Wooden Material at Oakbank Crannog

- 7 The Toolmarks at Oakbank Crannog

- 8 The Results of the Case Study

- 9 Comparing Axemarks to Known Tool Finds

- 10 The Use of Toolmark Results and Dendrochronology

- 11 The Potential Realised?

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index