- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The culture an organisation cultivates as an employer is just as important to its success as the brand image of its products or services. A culture that is at odds with the organisation's commercial activities is a very powerful signal to customers, employees and other stakeholders; it is a signal that will impact on the employers' sales, market reputation, share value and their ability to attract and retain the kind of employees that they need. In fact, employer branding is a complex process that involves internal and external customers, marketing and human resource professionals. Helen Rosethorn's book puts the whole topic into context, it explores some of the shortcomings of employer branding initiatives to date and provides a practical guide to the kind of strategy and techniques organisations need to embrace in order to make the most of their employer brand. At the heart of the book is the concept of the strategic employee lifecycle and ways in which an organisation should engage with potential, current and past employees. The Employer Brand focuses on the experiences and perspectives of organisations that have applied employer brand practices. It is a book about marketing - and the relationship of customers and employees; about culture - and the need for fundamental change in the role of the human resources function; about psychology - and the changing aspirations of the next generation of employees; and about hard-nosed business - and the tangible and intangible benefits of a successful employer branding strategy and how to realize them.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Employer Brand by Helen Rosethorn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE DEAL

1

Origins – Two Roots to the Family Tree

Let’s begin by explaining the thinking behind the title, The Employer Brand: Keeping Faith with the Deal. The intention from the outset has always been to avoid another academic explanation of the employer brand concept and to offer organisations working in this area something with a more practical application. The focus of the book is on the experiences and perspectives of organisations that have applied employer brand practices, rather than on academic definitions of the concept. Indeed, we hope that by featuring case studies and first-hand accounts from practitioners, other organisations will learn from these experiences and be prompted to share their own insights.

The real-world experiences of organisations that have begun an employer branding journey is the substance of the book, but it is important to first set the concept in an historical context. The notion of the employer brand is still a relatively young one, but it has its origins in distinct schools of thought. Armed with knowledge of these schools and where the concept began, we shall be in a better position to assess its strengths today.

Where Did the Concept Originate?

The idea of the employer brand emerged in the early 1990s, and a number of people laid claim to its creation. Rather than playing Solomon and sitting in judgement on these competing claims, we are going to use this first chapter to examine the origin of the concept and trace its development.

There are two roots to the family tree of the employer brand. The first lies in recruitment communications linked to the growth of the power of the corporate brand and the second in occupational psychology and, in particular, in the idea of the psychological contract. These two threads go back some way and, for many years, operated in parallel. But in the last decade – influenced by another key factor that we shall discuss later – they have combined to propel the concept of the employer brand into the limelight.

Advertising and the World of Work

Recruitment communications emerged as a specialism within the advertising industry in the 1960s. Recruitment messaging had, of course, existed before then, but the creation of specialist teams and then dedicated businesses to meet the desire of organisations to smarten up their ‘sits vac’ advertising really came to fruition from around 1958 onwards.

In the UK the catalyst was probably the growth of the search and selection industry. This sector had developed a critical mass and, by the early 1960s, executive recruitment firms were queuing up to place advertisements in the broadsheets of the time. The market was not particularly talent-constrained, but the column inches of the newspapers in those days did have limits so there was a sense of competition based on image and brand. In his book, The Employer Brand,1 Simon Barrow speaks about his early years in the advertising industry and the realisation that, as the specialism of recruitment communications matured, this sector could learn a great deal from classical marketing principles.

In the academic world a parallel development was taking place, which was to prove equally significant. Brand management was becoming recognised as a legitimate discipline and, for the first time, the ‘people dimensions’ of an organisation’s brand were being acknowledged and debated. Arguably, Bradford Management School was at the forefront of this breakthrough. At the time, the institution was divided between two schools of thought. Argument and discussion in the Business Strategy faculty was focused on a series of core strategy models which explained organisational behaviour and commercial success but left people out of the equation, relegating them to a footnote in operational logistics. Then, in the opposing camp, sat Philip Kotler and The Principles of Marketing2 Recognising that people are the biggest costs on the profit and loss account for many organisations and therefore that cultural and people-focused forces are powerful organisational drivers, Kotler encourages businesses to look at their people as consumers and to view the relationship between employer and employees – whether past, present or future – in terms of consuming a career or job.

It was a shift in perspective that opened up all sorts of questions and possibilities. If employees are consumers, how should employers create, define and package the product? What sales and marketing strategies should they adopt towards the job and how should product reputation be managed? Clearly, the new insight gave brand a central and defining role in commercial success.

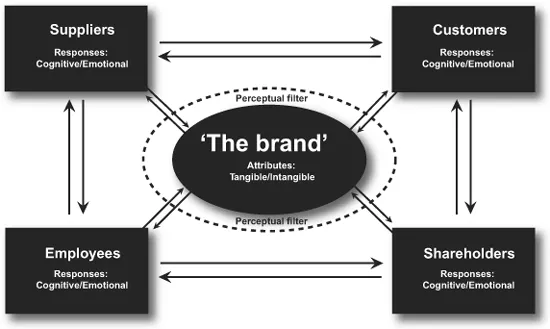

The thought leadership underway at Bradford Management School was crystallised in 1994 with the creation of the UK’s first chair in Brand Management. The first occupant of the new faculty was Professor Marc Uncles, an enlightened marketer who laid many of the academic foundations in this area. Happily, one of his early initiatives was a collaboration with Hodes that resulted in the model shown in Figure 1.1, which remains at the core of Hodes’s thinking today.

Clearly, we do not see the words ‘employer brand’. Rather, the model presents the employer brand as a subset of a central corporate brand, rather than as a standalone element. The brand consists of the perceptions of a number of distinct, but connected, audiences, one of which is employees – past, present and future. The model also emphasises that for many organisations there is one ‘master brand’ and that – as covered later in this chapter and in this book – this overarching brand is gaining in importance and impact in organisational life.

Figure 1.1 The brand and its stakeholders

In later chapters we will return to this model to assess its strengths and shortcomings, but it is worth highlighting its effectiveness at highlighting the relationship between the corporate and employer brand. It’s clear the employer brand can’t be defined, developed or managed in isolation from the corporate brand. Perhaps the relationship is not parent-child, but the two concepts are interconnected and we will examine exactly how once we have traced the development of the concept.

A World of Brands

At the same time as recruitment communications was coming of age the concept of the brand was gaining in momentum in many other ways. One of the best explanations of the journey of brands in recent decades has been written by the brand guru Wally Olins.3 As he explains in On Brand, brands were once a simple assurance of basic quality and consistency for goods and services, whether they were everyday consumer products or a safe place to put your money. The first mass-market brands were patent medicines which flourished by making extravagant claims about the benefits they could bring to their consumers. In particular, they made their mark in the US where patent and proprietary medicines were huge business in post-Civil War America.

Led by household product companies such as Unilever and automobile manufacturers such as Ford, brands began to change, thanks largely to an explosion in consumer advertising. In the wake of this, brand owners and managers introduced a more rigorously scientific approach into their work, and a raft of advertising theories had developed by the 1920s. Perhaps the most high-profile of these was the notion of the USP – unique selling proposition – the characteristic that makes any product or service distinctive and therefore uniquely attractive. Interestingly, Olins pours scorn on this approach: ‘Curiously, even today, among the more credulous and naïve members of the marketing fraternity, the initials USP still apparently possess some kind of credibility.’4

Olins talks about the 1970s as being a turning-point in branding for five main reasons:

1. the shift in power from manufacturer to retailer;

2. the rise of new forms of promotion away from traditional advertising;

3. new distribution systems and new media channels;

4. the emergence of new brands like Nike, Body Shop and Benetton that were not just brands, but new concepts in themselves;

5. an environment of wealth that was changing social, commercial and cultural behaviours.

We’d like to emphasise the fourth of these drivers because these organisations saw a future for branding that others only caught up with relatively recently. The Body Shop, led by its forward-thinking founder Dame Anita Roddick, was a case in point. The business redefined its sector and became part of a new breed of brands – a category that Olins summed up beautifully: ‘Most of them simply ignored the division between product and retail; they were products and they were retail. The brand wasn’t in the shop; it was the shop. And the brand was also the staff in the shop.’5

Roddick understood people power in building the Body Shop brand. In her book, Body and Soul,6 she spoke candidly about how employees were a vital dimension of her brand:7 ‘How do you ennoble the spirit when you are selling something as inconsequential as a cosmetic cream? You do it by creating a sense of holism, of spiritual development, of feeling connected to the workplace, the environment and relationships with one another. It’s how to make Monday to Friday a sense of being alive rather than slow death.’ Roddick and the people behind these new brands understood that brands were at least partly built from the inside – ‘bonding as much as branding’ to use Olins’ words.8

In the late 1800s and early 1900s this ‘bonding’ was centred on loyalty to a paternalistic or even philanthropic organisation. In the UK, places like Bourneville in York and Saltaire in Yorkshire exemplified this paternalistic form of affiliation, with large businesses providing villages for their workers and attempting to create a corporate family. But, as in every conventional family, there was a shared understanding of place and position. The hierarchy was set and supported by a well-developed command-and-control structure, although this was not a one-way relationship as members received fair treatment and a job for life.

The majority of businesses today don’t operate on these lines, and the consumers of jobs have changed, too. Job security is a thing of the past as companies grow and shrink, hire and fire. ‘Job consumers’ in turn have more choice and less affiliation to a single employer. They vote with their feet, more freely and happily than before, and loyalty to a corporate purpose is much harder to create and sustain. Research shows again and again that employees feel more loyalty to their colleagues than to the organisation, and these priorities are particularly prevalent in the attitudes of Generation Y as discussed in more detail later in this chapter.

Branding has changed, and the focus is now on involvement and association, or ‘the outward and visible demonstration of private and personal affiliation’.9 Olin comments that ‘when a brand gets the mix right it makes us, the people who buy it, feel that it adds something to our idea of ourselves’.10 And, importantly, this is equally true of employees as it is of consumers. Today, this sense of affiliation to a corporate purpose is central to the people power of a brand and is at the heart of a strategic definition for employer branding.

Incorporating the Psychological Contract

Earlier, we referenced a second root to the family tree of the employer brand: occupational psychology.

Another iteration of the idea of ‘bonding’ to a corporate purpose is the more contemporary concept of ‘engagement’. This notion has been at the top of the organisational agenda for some time, as it has a profound influence on corporate performance.

Since 1960, and particularly during the last 20 years, the examination of the psychological deal between employer and employee and its impact in the workplace has gained huge momentum. This has been reflected in the writings of Denise Rousseau and other academics. It’s not clear who first coined the phrase ‘the psychological contract’, but Rousseau has certainly been a leader in exploring and developing the concept in recent times.11 In the UK, Professor David Guest of King’s College, London, and Mike Emmott from the CIPD have also done substantive work12 using the CIPD’s annual employee attitude survey to research the changing impact of the contract for both employers and employees.

According to Rousseau, the psychological contract is the foundation of employees’ beliefs and behaviours in the workplace: ‘From the recruitment stage of an employee’s work life to retirement or resignation, it can have a profound effect on the attitudes and well-being of an individual.’ And she continues: ‘it is commonly understood as an individual’s belief about the terms and conditions of a reciprocal agreement with an employer or manager; a belief that some form of promise has been made and that the terms are accepted by all involved’.13

The issue, of course, is that this is unwritten and, unlike the written employment contract the majority of us are familiar with, highly flexible, not necessarily clearly defined and extremely open to interpretation by both parties. And as Rousseau sets out in her definition, it inevitably has a significant and determining impact on people’s behaviour and their demonstration of engagement or otherwise.

So why has ‘engagement’ grown in importance and apparently overtaken the psychological contract concept? It seems that the HR community has embraced the notion of ‘engagement’ because of its link to driving that elusive discretionary additional effort from employees that results in improved productivity and organisational success. Too few commentators appear to credit the psychological contract con...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Acknowledgements

- About the Author

- About the Contributors

- Foreword

- Preface

- Part I The Development of the Deal

- Part II The Deal in Practice

- Part III Striking the Right Deal

- Index