![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

Introduction

The idea for this book emerged from a three-year research project into the implications of digital technologies for book publishing in Australia (Martin and Tian 2008). In the event we realized that any such volume would be more meaningful if set in a wider context than that of Australian book publishing. Consequently, our treatment of the process of digitization in book publishing is set within the context of a global networked economy in which knowledge-intensive organizations have acquired an increasingly significant profile. Within the global markets that characterize this networked economy, the interplay between books, bytes and business is growing in both scale and complexity.

Book Publishing

The North American Industrial Classification System (NAICS) describes the publishing industry as a whole as one that produces a variety of publications, including magazines, books, newspapers and directories (NAICS 2007). It also produces greeting cards, databases, calendars and other publishing material, excluding software. The production of printed material continues to dominate the industry, although the marketplace now reflects the emergence of material in other formats, such as audio, CD-ROM, or other electronic media. Book publishing is different from other media sectors such as magazines, newspapers and journals. In dynamic markets characterized by great multiplicity in output, books are uncertain products that are also dependent on a high degree of creativity and individual attention. Understanding today’s book publishing industry involves acknowledging the growing concentration of resources, the effects of globalization, the changing structure of markets and of channels to these markets and the potential impact of new technologies (Thompson 2005).

Industry structure

The structure of book publishing can be variously perceived depending on the number and type of categories into which it is divided. Cheng (2004) categorized production according to consumer (or general) book publishing, covering a wide range of general interests; educational book publishing, covering schools and higher education; and professional book publishing, covering the areas of finance, legal, medical, scientific and technical publishing. All categories are dominated by large conglomerates that are responsible for a significant proportion of sales (Encyclopaedia of Global Industries 2007). At the time of writing (late 2009) there are 20 global publishing companies with revenues of over US$ 250 million. Allowing for various alliances and interconnections, some two-thirds of these conglomerates are located in Europe and the United States, with the remaining (Asian) third comprised mainly of three Japanese publishers (Wischenbart 2009).

Although the power and significance of such conglomerations are facts of life, this is not quite the whole story so far as book publishing is concerned. Even at the global level, there is still a place for numerous smaller and independent publishers that survive and, indeed, remain profitable by focusing their efforts on niche markets (IBISWorld 2010, Pira International 2002). An excellent example is the Lonely Planet Company, founded in Australia but now owned by the British Broadcasting Corporation, and which in many ways has set the benchmark for publishing guidebooks for travellers.

The nature of book publishing

In order to understand what is happening in book publishing today, it is important to take account both of change and of continuity. The effects of change are all around us and are exemplified by conglomeration, the restructuring of markets and channels, rising costs and competition and the all-pervasive impact of technology. Continuity can be seen in the continued role and perception of book publishing as being somehow different from the general run of commerce and, notably, as regards the cultural significance of its products and services (Thompson 2005).

In seeking to fund and profit from the production of these cultural artefacts, book publishers are especially vulnerable to changes in the demographics of the customer base and to increasing competition for time between the activity of reading and other, mainly electronic-based activities. To some, the sheer social and cultural significance of books, another dimension to their special status among consumer goods, renders their demise unthinkable. However, it is clear that books and the practice of reading face serious and immediate challenges, and it is less clear that the industry is capable of responding in the necessary manner.

One area of concern involves the perceived tardiness of the industry’s response to change in general, and to change involving digital technologies in particular. While it may still be too early to gauge the impact of the so-called ‘digital revolution’ on book publishing, it is also the case that much of the industry is involved to some degree with digital processes, whether the content is hard copy or electronic. There is, however, no substantial uniformity in approach, as each individual publisher has different requirements, characteristics and target markets, and hence they exhibit various levels of take-up of and involvement with digitization. What is clear, however, is that in the emerging digital environment, traditional ways of doing things will no longer be appropriate and radical changes will be required to ensure a viable, ongoing competitive future. Above all, publishers must now accept that theirs is an industry dependent upon the ability to produce what the end-user wants rather than what the publisher can give to them.

The role of publishers

Book publishing is the process of commissioning, producing and distributing books for sale. Traditionally the key players in the production channel have been authors, agents, publishers and printers. The key players in the distribution channel can be separated into distributors (sometimes the publishers), wholesalers, retail stores and book clubs, libraries and printers (Keh 1998). The range of players in both channels has increased even in the context of traditional print-based publishing, and it continues to expand with the onset of digitization. In both these channels, the publishing company still serves as the centre of gravity and plays a pivotal role in moulding the process. This is despite continued predictions that the uptake of digital technologies would result in disintermediation of the value chain for book publishing, given that authors could potentially perform all the roles involved, from creating the content to marketing and selling the finished product. In other words, authors would have the ability to become publishers. As with many technology-related predictions however, this one has not eventuated to any serious extent, and for good reason.

With their long experience of and considerable expertise in the book trade, publishers continue to add a considerable amount of value to the book publishing business. Publishers are not just another partner in the process. Rather, they are the major risk takers in what not infrequently can turn out to be extremely marginal ventures. They are responsible for everything from commissioning the book, to its design and production, marketing, sales and customer service. Over time the structures of the industry and the relationships between the players have changed as the result of a range of both internal and external forces, which will be explored in Chapter 2.

Key Trends in Book Publishing

Over the past decade, the global book publishing industry has been on a kind of roller-coaster ride, frequently alternating between turmoil and stability. This has brought change and disruption to markets and distribution channels, to products and formats and to business processes and practices. Traditional publishing markets have expanded to include opportunities in niche and specialist areas, such as those involving professional, educational and scholarly communities. New distribution channels and supply chains have emerged with the advent of the internet, and book publishers are using their web pages to communicate with authors and to provide a growing range of products and services directly to end-users.

Internet sales of print books continue to rise, as do sales of eBooks, albeit at a slower pace. Inevitably, such developments will add to fears of channel conflict and potential damage to conventional markets. Over the nine-week-long holiday sales period around Christmas 2009, in-store sales at Barnes & Noble fell by some 5.4 per cent to $1.1 billion, as compared with the same period in 2008. However, over the same time frame, online sales at BN.com increased by 17 per cent, peaking at $134 million. For the same period in 2008, Barnes & Noble had online sales of $114 million. Analysts agree that the increased figures for 2009 were a direct reflection of the launch of the nook reading device in November that year, estimating that nook revenues came to somewhere between $10 million and $20 million (B&N Press release 2010). The experience at Amazon.com was not dissimilar, with the company announcing that over Christmas 2009 customers bought more eBooks than hard copy books, again largely owing to the popularity of the Kindle (Amazon News Release 2010a). The subject of eBooks will be discussed in detail in Chapter 4.

The technology dimension

The most visible technologies in book publishing over the past decade have been the internet and the World Wide Web. However, at the core of technological change is the digitization of everything from content creation and editorial, to printing and distribution. At the most basic level, digitization involves the conversion of images, characters or sounds into digital codes so that the information may be processed or stored by a computer system. In this book, however, the use of the term ‘digitization’ goes beyond consideration of the functionality of individual technologies, to embrace their collective impact on organizational missions, structures, processes, cultures and behaviours. So far as book publishing is concerned, by enabling the conversion of data and information to electronic form, these digital technologies have the potential to transform the entire industry, from the creation of the book in digital form to its marketing, sale and even its use through a range of digital devices.

Today, organizations, including book publishers, typically employ a variety of digital technologies and applications, ranging from document management, workflow and collaborative systems, to enterprise resource planning systems and corporate portals. Digital technology has the capacity to act as an enabler in terms of production and distribution options, and of new products such as eBooks. It is impacting directly upon publishing costs through the provision of viable options in outsourcing and the subcontracting of specific business processes. Further, it is enabling the restructuring of firms and the industry as a whole, and is already transforming everyday marketing and communication practices. Not for the first time, however, there are at least two sides to this story, with technology retaining the capacity to be something of a two-edged sword. Hence, while undoubtedly helping book publishers with regard to competitiveness, costs and strategy, digital technology can also be a source of disintermediation, with the potential to increase the power of authors and readers and to disrupt industry and company value chains. In seeking to address such issues, the successful firms will be those that succeed in balancing the enabling power of technology, on the one hand, with the ability to exploit its potential to leverage the value of intangible resources, on the other.

The importance of intangibles

Within the global networked economy there have been fundamental changes to the organizational resource mix, with a high priority now afforded to acquiring, creating and capturing value from a broad range of intangibles. The acquisition of information and knowledge and their coordination and redeployment while learning from past experience is fundamental not just to continuous innovation, but also to competitive capacity and survival itself. It is obvious that technologies are undoubtedly an enabling force when it comes to facilitating the capture and transfer of information, here defined as data organized to characterize a particular situation, condition, context, challenge or opportunity. However, they are much less effective when it comes to the capture, codification and transfer of knowledge. For present purposes, knowledge is understood to consist of facts, perspectives and concepts, mental reference models, truths and beliefs, judgements and expectations, methodologies and know-how. Critically, it also includes an understanding of how to juxtapose and integrate seemingly isolated information items in order to develop new meaning and create new insights (Wiig 2004).

With knowledge now the predominant business resource, much of the emphasis in strategy today is on the acquisition and maintenance of the knowledge competencies and capabilities that are embedded in the social and physical structure of organizations across the spectrum from for-profit to not-for-profit operations. Whether viewed in terms of disciplinary domains, such as those of strategy or knowledge management, or of theories including, for example, resource-based or organizational learning theories, these developments constitute a significant shift in market and organizational dynamics.

Although information and knowledge have always been important to organizations, the recent shift in resource requirements, emphasizing the value residing in intangible assets, has produced a virtual step change in the level of this importance. The shift in emphasis from information to knowledge has been closely associated with the acquisition of the ability to connect information on networks. This connectivity, and its implications for interactivity, customization and learning, has extended not just to products and processes, but also to organizations, their structure and operations. It has also made a major contribution to the emergence of knowledge-intensive organizations.

Knowledge-intensive organizations

The rise of knowledge-based economies, and their links to innovation and rapid technological change, continue to have extremely significant implications for all kinds of organizations and their management. Furthermore, in what is a dynamic and often turbulent business environment, concepts such as industries, firms, suppliers, competitors and clients are all much less clearly demarcated than had previously been the case, with flux and fluidity apparent in both meaning and context. As a result, traditional command and control structures and classic bureaucracies are giving way to decentralized structures and to the employment of more flexible, fluid and integrated business processes.

Although the term ‘knowledge-intensive organization’ is socially constructed, there is more at work here than just simple perception. The concept relates to the kind of work performed in organizations and to the characteristics of the people who perform it. It embraces aspects of organizational infrastructure, of technology and human resource systems and structures, and involves a search for crucial synergies between people and work, innovation and creativity (Newell et al. 2002). As with many such popular terms, ‘knowledge-intensive organization’ comes with a level of intuitive plausibility, the most obvious examples coming from within the services sector. This plausibility was reflected in a notable description of service companies as being ‘brain rich’ and ‘asset poor’ (Quinn 1992). Nevertheless, it would be wrong to think of knowledge-intensive organizations as residing entirely in the services sector. Much of the early research into knowledge management occurred in the context of Japanese manufacturing industry, and also in the oil and agricultural chemistry businesses, involving companies such as BP Amoco and the then Buckman Pharmaceuticals (now Bulabs). Later, Heineken NV, the major multinational brewery, underwent a major organizational transformation by recognizing the value of strategic and operational knowledge. The goal was to leverage this knowledge within a horizontal, team-based structure based on soft networks of people, supported by hard networks comprised of personal productivity tools, communication tools and knowledge tools (Tissen, Andriessen and Deprez 2001).

However, within both hard and soft networks, the capture and transfer of knowledge is by no means a straightforward or routine affair. For example, although there are circumstances in which knowledge can be codified through embedding it in systems and structures, this not infrequently results in its becoming ‘sticky’, which is to say, resistant to transfer (Brown and Duguid 2001). In any case, simply codifying knowledge into a system does not necessarily make it usable for people working in a different time and space context (Swan, Robertson and Newell 2002). Consequently, there are other infrastructure elements at play within knowledge-intensive organizations, and specifically, structural and behavioural elements.

The need to create, develop and capture value from knowledge has had a significant impact both upon organizational architectures and on human resource management practices. So far as architectures are concerned, this can be seen in the emergence of everything from flat, flexible and competency-based organizational structures to those that are networked and virtual. To some extent these changes are a reaction to the perceived restrictions imposed by traditional bureaucratic arrangements, and a shift in the direction of structures where control based on professionalism and shared organizational values supplants that based on direct supervision and adherence to rules and procedures, thus providing the necessary environment for employees to enjoy autonomy and engage in creative and innovative behaviour (Newell et al. 2002).

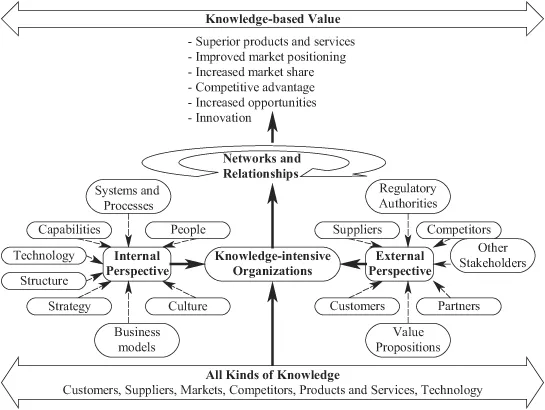

In the sphere of human resource management, there are implications for new roles, accountabilities and relationships, with senior management increasingly readjusting to a role that largely involves supporting and coaching teams of staff newly empowered to be proactive and creative. The basic objective of such adjustments to human resource management practices is to instil in staff the kinds of attitudes and patterns of behaviour that are perceived to be more suitable to the circumstances of knowledge-intensive organizations. These relate largely to recognition of the value of knowledge, and the inculcation of habits of collegiality and openness, leading to expected improvements in organizational climate and, especially, in conditions for the creation and sharing of knowledge. Put differently, this involves a search for organizational cultures that are knowledge based. This wider cultural dimension is captured in Figure 1.1, which presents an overall picture of the nature of knowledge-intensive organizations.

Figure 1.1 The knowledge-intensive organization

Two types of knowledge-intensive organization

Whatever their particular characteristics, or the industries and markets in which they operate, knowledge-intensive organizations can be divided into those for which knowledge is itself a product or service, and those for which it is a key business resource. Those in the former category make money either from creating knowledge and embodying it in new products and services (Nonaka and Takeuchi 1995) or from repackaging and reselling existing knowledge (Botkin 1999). Those in the latter category are skilled at acquiring and transferring knowledge, and at modifying their behaviour to reflect new knowledge and insights (Choo 2005). To some extent, therefore, all these knowledge-intensive organizations also engage in the practice of knowledge management, which for present purposes is understood as the process of creating, capturing and using knowledge to enhance organizational performance.

The rationale for knowledge-intensive organizations is that they are the logical response to a series of almost seismic commercial, regulatory and technological transformations that have taken place around the globe. These include radical shifts in the nature and composition of markets, in the locus of value and production, in the kinds of goods and services involved, and in organizational arrangements by way of response. Across the industry spectrum today, companies are faced with the same kinds of challenges and opportunities involved in...