eBook - ePub

Silver Economy in the Viking Age

- 244 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Silver Economy in the Viking Age

About this book

In this book contributions by archaeologists and numismatists from six countries address different aspects of how silver was used in both Scandinavia and the wider Viking world during the 8th to 11th centuries AD. The volume brings together a combination of recent summaries and new work on silver and gold coinage, rings and bullion, which allow a better appreciation of the broader socioeconomic conditions of the Viking world. This is an indispensable source for all archaeologists, historians and numismatists involved in Viking Studies.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Regions Around the North Sea With a Monetised Economy in the Pre-Viking and Viking Ages

D M Metcalf

The circular letter calling for papers for our symposium spoke of the transition from the gift/status economies of the pre-Viking Age to the monetised ‘nation states’ which were emerging by the end of the Viking Age. This view of the English Viking Age being, in my opinion, seriously out of touch with current research, I felt some doubts whether I could make any useful contribution to the occasion, but I wrote to ask Dr Gareth Williams whether a paper that might be thought controversial would be acceptable. He replied with exemplary serenity, ‘… by all means be as controversial as you like … the whole point of a symposium like this is for people to share their ideas with others, whether or not everyone agrees in the end. Certainly it often makes for a more interesting debate when people argue (constructively!) with each other’s opinions.’ Encouraged by this wise response, I should like to try to set out as clearly and accurately as possible the framework of the argument, as I see it, which says that in the pre-Viking-Age parts of England, and also other regions across the North Sea, had already developed an intensive money economy comparable with that which they enjoyed in the eleventh century. Between the two there was a monetary downturn in southern England, and similarly on the Continent. Pirenne could see the monetary upturn which followed, and mistook it for the beginnings of monetisation in north-western Europe. He was unable to see the preceding downturn, and therefore failed to do justice to the character of the economy in the early middle ages. Tenth-century numismatics, which tends to be difficult, has been intensively and very ably studied by a group of scholars of whom Christopher Blunt was the doyen. Tenth-century monetary history, which is another kettle of fish altogether, requires to be set into a wide context if the perspectives are to be accurately drawn. Between the eighth century and the eleventh, much of the economic infrastructure in southern England fell on hard times; wics and proto-towns were replaced by a new urban network. There is a considerable but scattered literature on monetary history, and the general historian may well be grateful for an overview. What he or she is most likely to need is a sense of how the arguments mesh together.

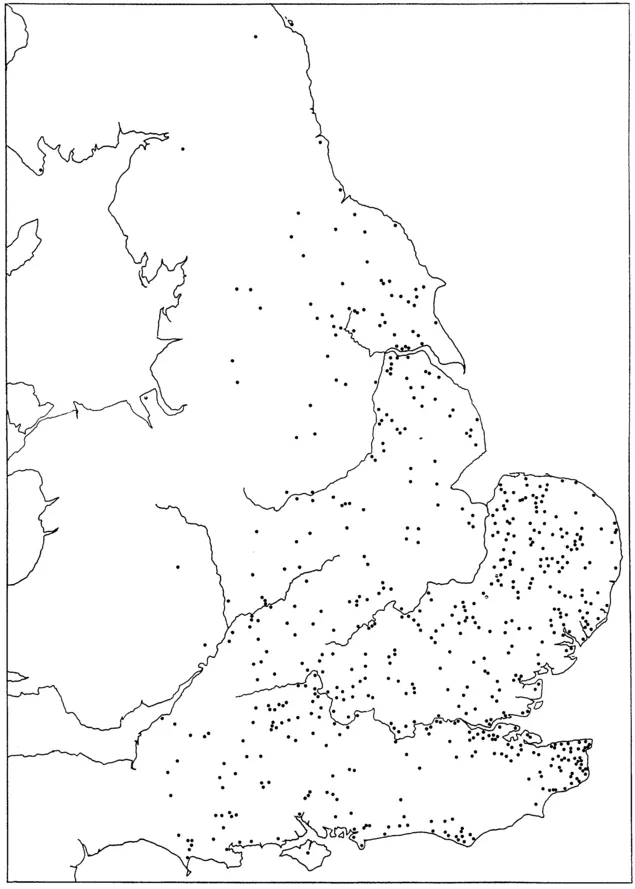

It is well enough known that in eighth-century England the degree of monetisation varied regionally, being much greater in the south-east and the east, and thinning out westwards to such an extent that the south-western peninsula, the whole of Wales and the north-west, let alone the Pennine region and Cumbria, were relatively coinless. The east-west gradient was evidently generated by trade across the English Channel and around the coasts of the North Sea (Metcalf 1989, 267–274). It is to some extent a perennial pattern in English monetary history throughout the early middle ages and indeed into the high middle ages. It does not correlate closely with regional prosperity, as we may judge from the Domesday Survey (Darby 1979, 200). Rich farming landscapes, for example in Herefordshire or Shropshire or in Somerset, have yielded extremely few stray finds of coins compared with Kent or East Anglia, a discrepancy by a factor of 10 or 20, whether it is viewed per capita or per acre. Similarly, the gradient does not correlate closely with political power. Mercia became a major player in the progressive consolidation of smaller tribal groupings, as the Tribal Hidage reveals (Hart 1977, 43–61), largely without the benefit of a money economy, and it was able eventually to gain the upper hand over the kingdom of the East Angles (Dumville 1989, 123–140) in spite of the greater monetary wealth of that kingdom. It is a similar story south of the Thames: the early primacy of east Kent (which surely reflects its locational advantages) is challenged by Wessex, in spite of the much later and weaker monetisation of the West Saxon kingdom.

What emerges as a conclusion clearly enough from all this is that monetisation in the pre-Viking Age was significantly linked with long-distance or inter-regional trade. Wics were the nodal points of the trade-routes: the wics of the Wantsum Channel; Ipswich; Lundenwic, Eoforwic, Hamwic. And the English wics are part of a larger picture, of trade around the North Sea coastlands, with Dorestad as the dominant centre, and again with some regions strongly monetised and others, such as north-eastern France and Belgium, much less so (Op den Velde, De Boone and Pol 1984, 117–145). The relative intensity of monetary exchanges in the hinterland of each wic seems to have varied, for reasons that are not clear. One might have supposed that the prosperity of the wic arose from the trade passing through it. But it seems that monetary exchanges may to some extent, and to a variable extent, have been concentrated in the wics, rather than evenly spread through the hinterland area which supported the urban economy: for example, farmers brought their cattle to market and, although they may have taken their money home again, it was in the marketplace that there was the greatest risk of accidentally losing a coin. Thus, Ribe, in Jutland, was a wic full of money (we can all, I hope, agree on that), yet finds of sceattas anywhere east of Ribe are exceedingly few, and not for want of searching.

The concentration of money in wics could also have been partly because that was where wealth was generated – not just the value-added wealth of traders who lived in the towns, but that produced by craft industries – comb-making at Ribe (Bendixen 1981, 200), glass-making at Hamwic (Andrews 1997, 216–218) and so on. Specialised production tends to require cash payments rather than barter.

When all is said and done, however, the wics are coastal: they are essentially ports prospering through maritime trade, and unless they were eking out a livelihood by taking in each others’ washing, that implies that a wic was functionally linked to its hinterland.

There is a problem of method, in that our impressions of the degree of monetisation tend to be based on the relative numbers of stray losses from this region and that. Although the chances of coins being accidentally lost are most likely to have been in direct proportion to the number of occasions on which they changed hands (rather than, for example, the size of the accumulated currency in a region), there are so many other unknown variables that the conclusion may be deemed unsafe, unless the margins of difference are very substantial. Different styles of husbandry, different settlement patterns, coins of different purchasing power – each may have had a significant effect on the statistics. Again, ratios of stray finds may not equate with ratios of stray losses for the purposes of the exercise, because of differences in the intensity of metal-detector searches or of archaeological excavations, or even of techniques of excavation. The uncertainties can to some extent be discounted, but it is well to remember that comparisons between regions based simply on global numbers of stray finds should be treated with caution. The east-west gradient of which we spoke is so pronounced and so widely evidenced that its significance is unlikely to be compromised by methodological uncertainties. The paucity of detector finds of eighth-century coins in westerly regions, for example, can be confirmed if one takes into account the relatively large numbers of Roman and other coins found by detectorists in those same regions. It is worth underlining that this paucity in the west is relative. It does not mean that coinage was virtually unknown there. At Bidford-on-Avon in Warwickshire, for example, a detectorist who has searched the area year in year out for 14 years, finding one or two sceattas a year, had at the last count pushed the total to 29 sceattas from this one village.

Having established the broad, regional perspectives, one can turn to the local topography, to marshal another argument, based on the contexts of the find-spots. There are now over 650 localities on record from which in total more than 2,360 single-finds of thrymsas and sceattas have been recorded in England (see the map, Figure 1.1) – far more than for eleventh-century coins (Metcalf 1998, 249–271). As regards the alleged gift/status economy of the pre-Viking Age, need I say more, really? Of the 650 localities, some include several separate sites within the boundaries of the same parish. The point to be seized is that the great majority of these 650+ localities (necessarily) are just villages, with nothing special about them. There is no visible correlation with royal manors, or with minster churches. There is no concentration of finds from royal centres such as Winchester or Tamworth (both well excavated). Coins have not been found in proximity to Offa’s Dyke. Sceattas were being lost predominantly in the course of ordinary village life, and, one must suppose, by ordinary people – everyday farming folk.

The acid test, general historians might be inclined to suppose, of whether coins were in widespread use for everyday purposes would be if they were ordinarily handled by women. A capitulary of Charles the Bald issued at Quierzy in 861, while specifying penalties for refusing good coin, goes on to exempt women from this provision, on the grounds that it is well known that they are accustomed to bargain before agreeing a price and making a purchase (Grierson 1990, 64). Legal documents rarely record such mundane details, which have the charm of immediacy. But one may well ask which is the better evidence, the anecdotal from which it may or may not be safe to generalise, or the more comprehensive review of a range of archaeological evidence.

If the latter is open, as a whole, to some residual doubt because of the unknown variables referred to above, there are, fortunately, some aspects of the evidence of stray finds which are much more secure. When coins from different mint-places, but of the same date and the same face value, mingled freely in circulation, they will arguably have been lost at random in respect of their mint-place, and the composition of the finds from a site should provide excellent evidence of the proportions, in the currency of that place, of the respective kinds and, by extension, of the relative scale of inter-regional transfers. In other words we are on much safer ground if we rely on within-sample variation. Thus, for example, the sharp contrast between the eighth-century finds from York (including its southern suburbium of Fishergate) and from Whitby (Rigold and Metcalf 1984, 245–268) respectively raises intriguing problems of interpretation. Another example: the relative

Figure 1.1 Distribution map of thrymsas and sceattas from England.

scarcity of the locally minted sceattas of Series H anywhere outside Hamwic itself has prompted the suggestion that the wic enjoyed a positive balance of payments through its trading (and craft) activities, and that this was reflected in unusually small monetary outflows (Metcalf 1988, 17–20).

The other leg of the argument from the mingling of coins of different mint-places depends on estimates of the quantities of coins minted, as judged from the numbers of dies employed. This argument is stronger when applied to active mints, which were using up reverse dies at such a rate that one need not worry too much about the possibility of serious under-use of dies. Taken by itself, the argument from quantities of coins minted might be depreciated by saying that most of the coins could have served only or mainly as a store of value, and that they should not be assumed to have supported an exchange economy. That is something which one cannot altogether discount, except by saying that if coins were in such widespread use, most of the people who were using them were necessarily ordinary people who would not have had large-scale surplus wealth. But when the two arguments are combined, and set into the context of regional currencies, one obtains very specific and powerful evidence of the scale of inter-regional monetary transfers. These are the twin pillars on which the case rests: not the seven pillars of wisdom, nor the five pillars of religion, but the twin pillars of monetisation – quantity in combination with velocity. On the conventional estimate that 100 dies could be used to strike something like a million coins, it is clear beyond reasonable doubt that millions of coins were involved in inter-regional transfers within England, and that the scale of the currency accumulated within Hamwic, for example, was of the order of some two or three million coins.

We now know, through the patient researches of Derek Chick, that the coinage of King Offa was struck from an estimated 1,000 to 1,100 dies, with little room for statistical error, pointing us towards an output figure of the order of 10 million coins. For the preceding sceatta coinages, evidence of the same high quality is not yet available, except for Northumbria, but it has been conjectured that they were produced, admittedly over a period of nearly 100 years, from a grand total of roughly 8,000 dies, therefore perhaps 80 million coins in all. Of course these totals are dependent on the assumption of 10,000 as the average output of a die, as is the corresponding estimate for Offa, and they may accordingly be somewhat wide of the mark, but not so wide as to threaten the general conclusion that the pre-Viking-Age economy was strongly monetised in some regions, and relatively much less so in others, with maritime trade in the English Channel and on the North Sea coasts as the driving mechanism.

Of all the sceattas found in England, a good 14 per cent are of the ubiquitous ‘porcupine’ type, minted in the Rhine mouths area, largely at Dorestad (Metcalf 1993–94, 174). Dorestad, with its miles of quays (Van Es and Verwers 1980), was the Rotterdam of the day, a major commercial port serving as intermediary between the trade of the Rhine valley, and in the other direction the trade passing through the wics of the North Sea coastlands, all around from Northumbria to Jutland. A seventh of all the money in England had originated in the Rhine mouths area. We can safely say that millions of porcupines accumulated in England. And then there are the plentiful Frisian runics, Series D, which also reached England in quantity, and the Wodan/monster sceattas of Series X, minted in Ribe. In light of our discussions at the symposium (see Malmer, Chapter 2, in this volume), it is necessary to add that the arguments for the attribution to Ribe (Metcalf 1984, 159–164) have been disputed, but have recently been restated without retraction (Metcalf 1996, 403–409). Together the foreign sceattas found in England represent a massive balance-of-payments surplus, generated (how else?) by exports. They did not reach England through gift-exchange, or as status-symbols (Hodges 1982; Hodges and Cherry 1983, 131–183). The scale of the exchanges is such that most of those exports were almost certainly farm products of one sort or another. It would seem that regions such as East Anglia were producing for an export market to an appreciable extent. And on the Continent too, there seem to have been sharp contrasts between the heavily monetised and the lightly monetised regions – the Rhine mouths area, for example, in contrast with the coastlands further west in Belgium and Picardy (Delmaire, Gricourt and Leclercq 1990, 179–185). Detectorists’ single-finds accumulate steadily in the Netherlands: the KPK maintains a register of them, and coin dealers regularly sell provenanced sceattas.

I have concentrated on the logical framework of the argument, with the minimum of details by way of example, and those drawn mainly from the first half of the eighth century, because that is where the case stands or falls. It offers a view of the pre-Viking Age which is sharply at variance with the general ideas of historians of an earlier generation. If this argument had been available to Pirenne, he could not have formulated his famous thesis in the way he did. No blame attaches to him: in the country of the blind, the one-eyed man is king. But there is no occasion to be one-eyed about the evidence available in 2000. Pirenne could not know what we know now, nor could he have shared the ideas that govern our thinking, for several reasons. First, the number of eighth-century coins above-ground has increased many times over, primarily by the activities of metal-detectorists, allowing us to construct die-catalogues large enough to serve as a basis for statistically reliable die-estimation. When there were only half-a-dozen specimens of a variety in existence, the absence of die-duplicates among them was neither here nor there, and there was no immediate reason to suspect the large scale of the issues. Second, there has been a 30-year-long debate among numismatists about the appropriate methods and practical problems of statistical analysis (Carcassonne and Hackens 1981), with a growing awareness of the historical implications of the numismatic facts, or better one could say, the facts about monetary circulation and monetary history that are being created through the recordin...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Notes on Contributors

- Preface

- List of Abbreviations

- 1 REGIONS AROUND THE NORTH SEA WITH A MONETISED ECONOMY IN THE PRE-VIKING AND VIKING AGES

- 2 SOUTH SCANDINAVIAN COINAGE IN THE NINTH CENTURY

- 3 HEDEBY AND ITS HINTERLAND: A LOCAL NUMISMATIC REGION

- 4 THE EVIDENCE OF PECKING ON COINS FROM THE CUERDALE HOARD: SUMMARY VERSION

- 5 GOLD IN ENGLAND DURING THE 'AGE OF SILVER' (EIGHTH-ELEVENTH CENTURIES)

- 6 A SURVEY OF COIN PRODUCTION AND CURRENCY IN NORMANDY 864-945

- 7 VIKING ECONOMIES: EVIDENCE FROM THE SILVER HOARDS

- 8 ORIENTAL-SCANDINAVIAN CONTACTS ON THE VOLGA, AS MANIFESTED BY SILVER RINGS AND WEIGHT SYSTEMS

- 9 THE FORM AND STRUCTURE OF VIKING-AGE SILVER HOARDS: THE EVIDENCE FROM IRELAND

- 10 TRADE AND EXCHANGE ACROSS FRONTIERS

- 11 KINGSHIP, CHRISTIANITY AND COINAGE: MONETARY AND POLITICAL PERSPECTIVES ON SILVER ECONOMY IN THE VIKING AGE

- 12 REFLECTIONS ON 'SILVER ECONOMY IN THE VIKING AGE'

- INDEX

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Silver Economy in the Viking Age by James Graham-Campbell, Gareth Williams, James Graham-Campbell,Gareth Williams in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.