eBook - ePub

Changing Organizations from Within

Roles, Risks and Consultancy Relationships

- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Changing Organizations from Within

Roles, Risks and Consultancy Relationships

About this book

Organizational change is often insider-led and supported by internal consultants and change agents. Most of what is written about change comes from the perspective of external consultants or from academics researching the activities of those with insider change roles. Changing Organizations from Within is unusual in providing a range of authentic insider accounts. The editors define 'insiders' as employees who lead and support change efforts within their own organizations, and those psychoanalytically aware external consultants - external 'insiders' - who work closely with organizations and use the dynamics of transference and projection in their relationships with clients to illuminate organizational issues. Each chapter is written by an author with experience of different kinds of insider relationships with their client organizations. Some work 'inside' as employees. Some are external consultants whose work involves developing insightful insider perspectives. The book's editors and several of the authors are graduates, or have been faculty members, of London's Tavistock Institute Advanced Organizational Consultation programme, with experience of running development programmes for consultants and of coaching insiders. Changing Organizations from Within examines the pulls on role and identity that can easily undermine competence and practice. Understanding the system psycho-dynamics present in organizations helps consultants and change agents to make use of an insider perspective without becoming enmeshed in the client organization's regressive and inertial dynamics. The authors provide practical advice to help insiders navigate organizational space, make sense of tricky situations, and work more mindfully to help organizations change.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Changing Organizations from Within by Robin C. Stevens, Susan Rosina Whittle in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Power and the Internal: Working on the Edge

Power is anything that tends to render immobile and untouchable those things that are offered to us as real, as true, as good. (Foucault 1988: 1)

I consider the practice of organization consulting to be in essence a political process as it is influenced by and influences the distribution of power in an organization. Consultants participate in these processes in their client systems and cannot stand outside of them. My intention in this chapter is to explore this aspect of internal consulting by examining how internals can understand and work with power dynamics in organizations. If we look a little closer, we can see that much of what we do as consultants is associated with questions of power, for instance:

• Who can authorize me to take up my role in the system and for what purpose?

• Who will pay for my time and what do they expect in return? If I am an internal, how will my contributions be recognized? What limits do I put on my involvement?

• Who will be involved in the consultation and whose interests will be considered?

• How do I understand the underlying issues and how might my account and that of others be contested?

• Who wants change, in what form and for what purpose? How will such desires be resisted and by whom?

• How will changes be brought about and who will be involved?

• Who will and how will my work be evaluated?

In most organizations, however, power is rarely questioned or openly explored. Moreover, individuals tend to discount their own political motives and behaviour while describing others’ behaviour as ‘being political’. This challenges the consultant to make decisions about how to make sense of and work with power. It presents a dilemma as to whether to act in a manner that maintains the existing power dynamics or seeks to disturb them. This is the line of enquiry that I wish to pursue in this chapter. Firstly, by considering how we can understand and work with power as consultants, and secondly by reflecting on my experience of power dynamics when I worked as an internal.

Power Dynamics and the Internal

Earlier in my career, I worked for eight years as an internal Organizational Development consultant in a large global multinational manufacturing business. Over this period, I developed a rich and subtle understanding of how power was enacted in the organization and how to navigate sensitive political relationships. This is one of the primary advantages of internal consultants in comparison with externals (Scott 2008). While achieving insight into the power dynamics, I was also aware that my interests tended to be dependent on how I connected with and aligned myself with individuals who held power in the organization. Looking back now, I can see that I became so attuned to the power dynamics in the organization that I was unaware at times of how I participated in them. On reflection, I was trying to balance a distinctive identity as a practitioner while being accepted as an ‘insider’ who had access to formal and informal networks. I could not rely on my position in the hierarchy for authority and like most internals I had to rely on my professional credibility and internal relationships as a source of power (Wright 2009).

To take up their role, internals are challenged to maintain a marginal position which requires them to operate at the edge and on the boundary of the organization (Scott 2008). I experienced this to be a constant struggle. To influence change, I often found myself working through the existing power structures, yet paradoxically my practice often involved an implicit or explicit challenge to how power was configured in the organization. This paradoxical position is, I believe, central to the internal role. In the case I explore below, it appears in multiple relationships throughout the consulting assignment.

A FRAMEWORK FOR UNDERSTANDING POWER

The concept of power is ‘essentially contested’ (Lukes 1974: 14). It remains ambiguous, abstract and elusive (Eriksen 2001). Yet in spite of this, I believe it is a valuable concept as it provides a conceptual link between the person and the group, and the individual and society. It helps us understand who may do what, where and in what ways in a given social context.

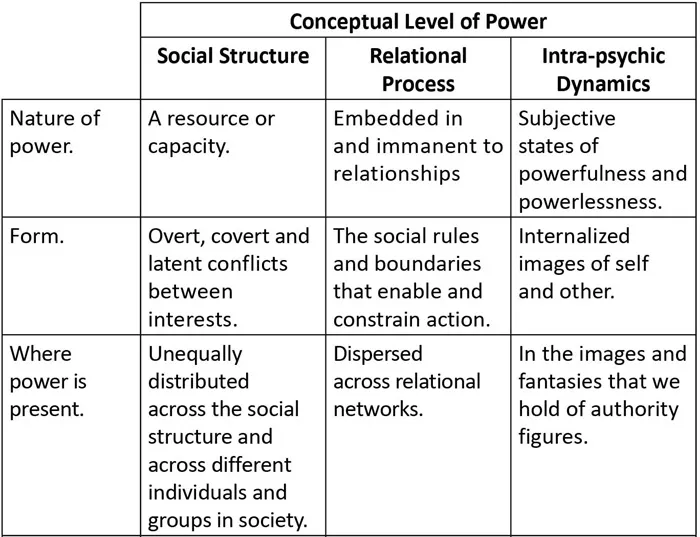

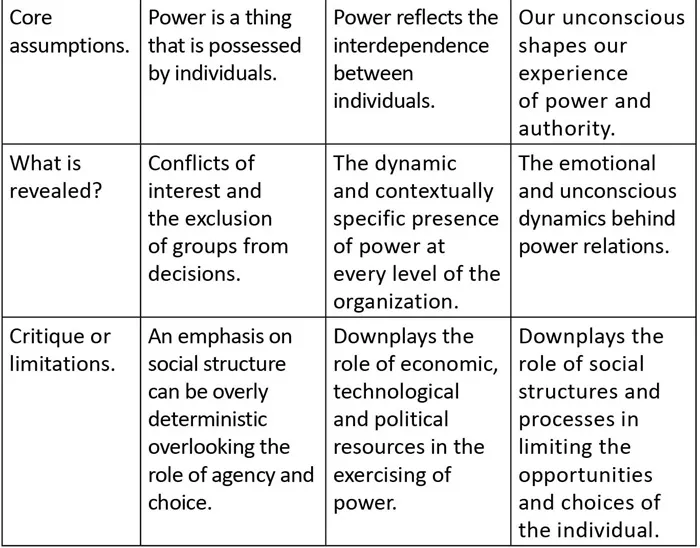

In my practice I conceptualize power to be operating at three related yet distinct levels. These are the levels of: social structures, relational process and intra-psychic dynamics. Table 1.1 below describes the three conceptual levels and summarizes briefly how the sociological, political and psychological theory conceptualizes each level.

Table 1.1 The different conceptual levels of power

Power as a Social Structure

Structural accounts of power emphasize how power arises from the relatively fixed aspect of the social structure of societies and organizations within them. Power is formed by the tacit and taken-for-granted basis of the social order which becomes legitimized through the use of symbols, language, rituals and normative assumptions (Pfeffer 1981). As such, differences in power become embedded in the fabric of society. This results in the social stratification of groups within societies and the unequal distribution of social status, privilege and materials on a systematic basis (Crompton 1993).

Marxists and feminists have observed how these structures tend to be organized along class, racial and gender divisions. Power is inextricably linked therefore to socio-political identity groups. As practitioners, we need to be aware of how our position in society has shaped and influenced our identity, view of the world and others. I am white, British, middle class, male and professionally educated. My life history is not therefore an experience of being oppressed, marginalized or discriminated against. I have experienced power from a position of privilege and opportunity which will be reflected no doubt in my consulting practice. You, the reader, may well see ways in which my position in society shapes how I engage with power in the case I present below.

Structural accounts define power to be the ability to get others to do what you want them to, if necessary against their will (Weber 1978) or to get them to do something they otherwise would not (Dahl 1957). The assumption being that power is a capacity or resource that is possessed by individuals. Sources of power include: information, expertise, credibility, control of rewards, status and access to influential individuals (French and Ravens 1968). This perspective highlights the role of political elites, political coalitions and organized interest groups, such as unions and professional bodies, in organizations.

The structural perspective draws our attention to how actors in organizations exercise power to further their interests when they conflict with others’ interests. This is most visible during periods of overt conflict or power struggles in an organization. Lukes (1974) observes that power can be exercised in more hidden or subtle forms. He argued that it can be used covertly to prevent the interests of specific groups from being represented or considered in decisions. This involves either the mobilization of bias (Bachrach and Baratz 1970) to shape decisions or the prevention of decisions from being discussed or acknowledged publically. He also draws attention to how power can be used to prevent overt and covert conflict from arising in the first place. In this form, power is used to shape the consciousness of others such that they come to accept the existing social order either because they see others’ interests as being their own or they are not able to identify their own interests. For Lukes (1974: 24) this is ‘the most effective and insidious use of power’ as it leads to what Marxists have termed ‘false consciousness’ and ‘alienation’ whereby conflicts remain at a latent level. What are the implications for practice?

• Organizational development is likely to require the formal exercising of power by individuals in positions of authority to make decisions and legitimize forms of organization change. The internal consultant’s influence and authority is frequently dependent on the degree of support that they receive from individuals who hold power and authority in the organization. As such, we become implicated in the existing structures of power and if we are not simply to reinforce the existing structures to further our own interests, we need to take a critical stance on our positioning in the established structures.

• Changes to organizational practices will give rise to overt, covert and latent conflicts between different interest groups in the organization as power structures shift. Conflicts will also reflect fears and vulnerability around real or potential losses of power. The internal consultant will need to make decisions about how, when and whether to facilitate the exploration of such conflicts.

• Planned and emergent change often requires consultants to involve individuals and groups that have previously been excluded from formal and informal decision-making processes. The internal consultant will need to make decisions as to when and how to bring different voices into negotiations and decision-making processes that relate to the change processes.

Power as a Relational Process

A relational perspective highlights how power is not simply held by specific individuals or groups but is present at every level and sphere of life, affecting the powerful and the powerless. It reveals the dialectic nature of power relations whereby the balance of power is held between individuals rather than by them (Giddens 1984). For every act of power we can also expect to find forms of resistance or acts that work against it (Foucault 1980). Power is therefore dynamic, constantly shifting and, at times, paradoxical. It is an inevitable outcome of living together and interdependence (Elias 1978).

Power relations represent the social boundaries that constrain and enable action (Hayward 1998; Elias 1978). They are inscribed within the contextual ‘rules of the game’ (Clegg 1975) and are played out through the strategies and skills that actors exercise in the enactment of them. Power dynamics revolve around the processes of inclusion and exclusion (Elias 1978) as groupings are formed through social interactions. This gives rise to an ‘Us’ and a ‘Them’. For me, paying attention to power dynamics highlights how formal and informal relationships enable action and change, while in doing so they necessarily exclude people who are outside of specific social connections or groupings.

Power is enacted through social discourse whereby different actors position themselves in relation to others according to their status and identity. We typically experience this process in the form of status games that are played out in groups and interpersonal relationships. Power can also be equated to claims to knowledge (Foucault 1972). Different discourses and ideologies represent bodies of knowledge which form the basis of social practices (Foucault 1972). Foucault (1980) observed how ‘regimes of truth’ – unquestioned patterns of discourse – are established in society to create our reality. These ‘regimes of truth’ become a means of preserving the current social order by making it seem natural and unquestionable.

Power as a relational process brings into view the taken-for-granted, tactical and unobtrusive presence of power in the interactions between multiple agents in a social system. It illuminates how power arises through relationships with others and moves towards power residing on the consent of others (Hindess 1996). What are the implications for practice?

• Social boundaries and the implicit ‘rules of the game’ put limits on what forms of action are acceptable in organizations. If different social rules are to emerge, then the internal consultant will need to find ways of helping a client system become aware of how they enable and constrain different forms of action. This is likely to require the questioning of dominant patterns of discourse and what is presented as right and normal and what is seen as wrong and deviant.

• The nature and form of problems and issues experienced by a client system will be contested between different groups and individuals. The internal consultant will need to make decisions as to how they raise and question different accounts and positions in a manner that does not result in them being excluded by influential parties.

• Creative and generative forms of power will involve groups of people coming together to negotiate how they can work together to achieve outcomes that they could not achieve individually. This is likely to require the internal consultant to work both through formal and informal relationships to develop common ground and consensus amongst different actors.

Intra-psychic Dynamics of Power

Psychodynamic theory argues that how we engage with authority figures and exercise our power reflects our unconscious, internal world. Both Freud and Lacan took the position that the family, society, gender and each of our lives are constructed on the premise that power is unequally distributed. We are all highly ambivalent about power, as a result of the struggles that we encounter with early authority figures. These early relational experiences give rise to internalized images of benign or punitive authority (Hirschhorn 1988) which shape how we experience power relations in our later lives.

Our internalized images of authority can be evoked when we encounter authority or take up a position of authority. We often project benign or punitive images onto individuals in positions of authority. This shapes how we participate in power relations, our sense of personal authority and experience of authority figures. We may therefore perceive individuals in power as being critical of us, aggressive, lacking in some way or in contrast we may idealize them and see them as all powerful. Our images of authority can give rise to beliefs and fantasies as to what we are able and permitted to do in our roles or the extent to which we need to feel controlled by or in control of others. They can often lead to pejorative judgements of individuals in positions of power or those who are perceived to stand in opposition. When holding positions of authority we can equally project onto others and assume that they may hold the same images of ourselves as we hold of authority figures. This can prevent us from taking up our role and authority.

Our own narcissistic process can lead us to feel omnipotent or impotent in our work with clients, believing we are either all powerful or powerless. Consultants and leaders are prone to both hubris and helplessness and to despair in their roles. These polarized positions arise from the vulnerabilities and fantasies of the role holder and projections from the client system. In my practice, I can find myself acting on the belief that I can change the organization or, in contrast, believing that I am utterly powerless to make any difference in my role. Neither position is helpful to either myself or my client, although, if I can tolerate and explore my response, I may be able to reach an understanding of my reactions. From this perspective, the challenge to the internal consultant is to remain grounded by staying in touch with one’s capabilities and with the limits of what is possible in a given context. What are the implications for practice?

• Primitive emotions, such as envy, aggression or fear, tend to get projected onto individuals at the top and bottom of power distributions. The internal consultant as a figure of authority is also likely to be a recipient of such projections from others. Consultants need to tolerate and contain such projections if they are to support individuals and groups to work through the emotional material that relates to the consulting task.

• Internal consultants need to find ways of containing the anxieties and vulnerabilities of individuals and groups to help them to own their projections. This enables individuals to constructively negotiate and assert their interests during periods of organizational change. In order to facilitate this process, internal consultants will need to be able to take up their authority, clarify roles and hold boundaries.

CASE STUDY: EXPERIENCES AND REFLECTIONS ON POWER AS AN INTERNAL

This case describes my experience of power dynamics in an internal consulting project. At the time I was working in the role I referred to earlier in the chapter. I have referred to the organization as Global Corp (GC) to protect its identity and have chosen not to name individuals who were involved. In the case, I have described my experience of power dynamics at each of the three levels and discussed how power shaped the consulting work.

In the spirit of this chapter, I want to acknowledge that as the author I have the power to construct a narrative that portrays others and myself in a particular light. I have chosen not to comment on interpersonal dynamics, as I do not have the other person’s account to supplement my own. This is most apparent in my decision not to describe in detail the relationship with my colleague at the time. Our relationship was for the most part collaborative and collegial. My reflections are based on my personal experiences of power dynamics in the client system and interview material ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- About the Editors

- About the Contributors

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Consultancy Roles, Risks and Relationships

- 1 Power and the Internal: Working on the Edge

- 2 Strategic Moments in Internal Consulting: Introducing Functional Learning Environments in a Social Care Organization

- 3 Dining with the Devil

- 4 Managing Projects: How an Organization Design Approach Can Help

- 5 Quick, Quick, Slow: Time and Timing in Organizational Change

- 6 Family Business: Inside and Outside the Systems at Play

- 7 By Invitation Only?

- 8 Too Close for Comfort: Attending to Boundaries in Associate Relationships

- 9 Theory for Skilled Practitioners

- Index