eBook - ePub

The Psychology of Marketing

Cross-Cultural Perspectives

- 414 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Psychology of Marketing

Cross-Cultural Perspectives

About this book

This comprehensive guide to both the theory and application of psychology to marketing comes from the author team that produced the acclaimed Customer Relationship Management. It will be of immeasurable help to marketing executives and higher level students of marketing needing an advanced understanding of the applied science of psychology and how it bears on consumers; on influencing; and on the effective marketing of organizations themselves, as well as of products and services. Drawing on consumer, management, industrial, organizational, and market psychology, The Psychology of Marketing's in-depth treatment of theory embraces: ¢ Cognition theories. ¢ Personality, perception and memory. ¢ Motivation and emotion. ¢ Power, control, and exchange. Complemented by case studies from across the globe, The Psychology of Marketing provides a trans-national perspective on how the theory revealed here is applied in practice. Marketers and those aspiring to be marketers will find this book an invaluable help in their role as 'lay psychologists'.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Psychology of Marketing by Gerhard Raab,G. Jason Goddard,Alexander Unger in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Market Psychology in the Context of Systematics

Many psychologists working today in an applied field are keenly aware of the need for close cooperation between theoretical and applied psychology. This can be accomplished in psychology, as it has been accomplished in physics, if the theorist does not look toward applied problems with high eyebrow aversion or with a fear of social problems, and if the applied psychologist realizes that there is nothing so practical as a good theory”

(Lewin, 1944)

The Subject of Market Psychology

As a science, market psychology explains and predicts human behavior with regard to markets. We can speak of a market whenever something of worth to someone is being exchanged for something else.

The most popular market is the goods market, within which goods of a material or immaterial kind are exchanged for money. In these markets the striving toward financial profit is a definitive determinant of supplier behavior. Buyers are looking for utility (buyers of productive goods) or for satisfaction of desires or needs (buyers of consumable goods). Regular exchange also occurs in cases where striving for profit is not the essential goal. If a governmental department starts a communications campaign against drink driving, then it is offering something (safety, health), and receives as a return the curtailing of alcohol consumption. That is an example of non-profit marketing and at the same time of social marketing. The situation of parties working against each other for votes in an election is also a market, in that trust in the election platform is being exchanged for votes. Another example of a market is the financial market, including the stock market. All of these examples are indisputably relevant within any discipline that calls itself “market psychology”.

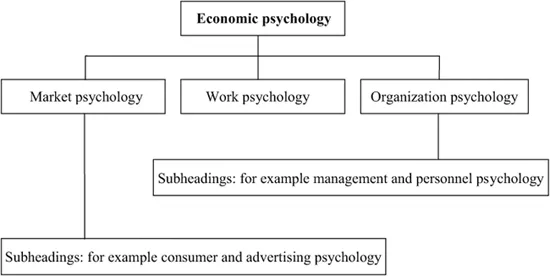

Wiswede’s (1995, pp. 14–18) treatment of economic psychology is considerably more extensive. This subject includes, according to Wiswede (1995, p. 17) “special economic psychology” topics like work and organizational psychology, especially with regard to the related discipline of management psychology. For Wiswede savings behavior, perception and reaction in relation to inflation, also belong to economic psychology. Certainly it is self evident that in these areas exchange processes can also be postulated: In the area of management behavior a particular type of work performance is exchanged for incentives (of a material or immaterial kind); the same goes for human resources management or for organizational psychology.

Saving means nothing more than momentary renunciation of consumption in exchange for a reward (interest). If it in fact has to do with reaction to price changes, reaction to inflation is included within the scope of the goods market described initially. Taxation is also nothing other than a fee in return for service. It lacks the element of free will however. Seen in that light, the element of taxation certainly does not belong within market psychology.

To us it seems a bit arbitrary, starting from the point of view of a field of market psychology on the one hand, and from a field of work and organization psychology on the other hand, to exclude certain exchange processes from the field of market psychology, and then, aside from market psychology, to assign these elements within an overarching field of economic psychology. Kieser and Kubicek (1992, p. 10) clearly perceive the possibility of understanding customers or clients of organizations as also being members of those organizations, so that these members then influence the organization’s decisions. As an outgrowth of this viewpoint Irle comes to a conclusion whereby consumer psychology is understood as “a special offshoot of organization psychology”. According to Wiswede economic psychology can be presented as in Figure 1.1 below:

Figure 1.1 Subheadings of economic psychology (from Wiswede, 1995, p. 17)

Since we are starting from a comprehensive market concept, we can also proceed according to a comprehensive market psychology that can be divided at will into many different subheadings. Which subheadings result from this and how they are ordered depend, among other things, on the individual researcher. The meaning of whatever classification is chosen will prove itself, as a hypothesis, during the course of the research process.

In market psychology we have that science which explains behavior within all markets: consumer psychology, work psychology, organization psychology, management psychology, communication psychology, media psychology, and the psychology of decision making, are all special disciplines which certainly can overlap. Where there is a market for health products and for behavioral advice relevant to health, even parts of health psychology can be considered to be aspects of market psychology.

Market Psychology as an Applied Science

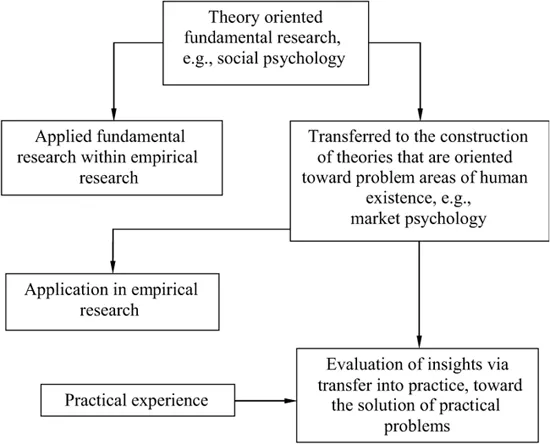

We can differentiate between three levels of research: The level of fundamental research, that of applied research, and the level of evaluation of scientific findings in practice.

Fundamental research is theory oriented. It seeks insights in order to advance itself. It is a continuous, never-ending search for ever-better explanations for all manner of phenomena. It would be misguided to measure fundamental research on the basis of its future “utility” (however that may be understood). On the way to discovering new insights it can never be said to what use they will be put. Having said that, practitioners seeking insight need an arsenal of proven theoretical findings, just as practitioners of applied research do. In general it is not economical to begin by searching for new solutions to problems with the advent of every problem. The worth of scientific insight lies in already available, generically valid theoretical statements, which can be applied to any number of problem areas, or which simply further the process of gathering insights. Examples of fundamental research areas are: psychology, social psychology, sociology, pure economics, biology, chemistry, and physics. All of these areas have one procedure in common: Insights are sought on the basis of specific theoretical concepts. The field of application could then be anything.

Applied research on the other hand is oriented toward problem areas of human existence that need to be explained. Some examples are: pedagogy, interaction psychology, market psychology, marketing, medicine, and research into well-being. The problem area is given, and then solutions can be sought and brought to bear on the existing problem from any number of fundamental research areas. Admittedly there then arises the danger of arbitrariness. Since the arsenal of theoretical statements from the area of fundamental research has become extremely large, the possibility can certainly be seen of arbitrarily construing a theory within the applied science, and then to convincingly support this theory via equally arbitrarily selected areas of fundamental research. From the point of view of scientific theory however, this is entirely unproblematic. Through the inductive transfer of theoretical and completely proven scientific pronouncements, no new insight is culled concerning new areas. Obtainment of scientific insight is only possible through the empirical testing of theories. The construction of theories in applied science, through the creative use of proven theories from fundamental science research, is to be seen as a phase of hypothesis formulation. There is no “restraint to method” here at all. Here, but truly only here, can we follow Feyerabend’s plea against restraint to method (Feyerabend, 1993). Otherwise we are proceeding according to a strict, scientific, deductive approach, which amounts to formulating provable hypotheses, rather than exposing their flaws toward the end of testing them for truth content. The deduction phase follows: a critical examination according to empirical method. It does not make any difference how systematic or arbitrary, plausible or implausible the constructed hypotheses are; if they prove themselves now we can keep them, and if they fail the test we can go back to the drawing board, check over the reasons for their flaws, correct them, bring them back into play, and test them again. Or we reject them for the time being (just as there is no conclusive proof as to the final verity of a hypothesis, it is similarly the case as to the definitive failure of a hypothesis). The analysis of market events is an example of applied science. When we speak of market psychology, it is thereby being indicated that we want to elucidate market events by using psychological theories.

From the beginning it is being stated that problem areas of human existence should be explained. Closely related with that, and what for later evaluation in practice is of great significance, is the prognosis.

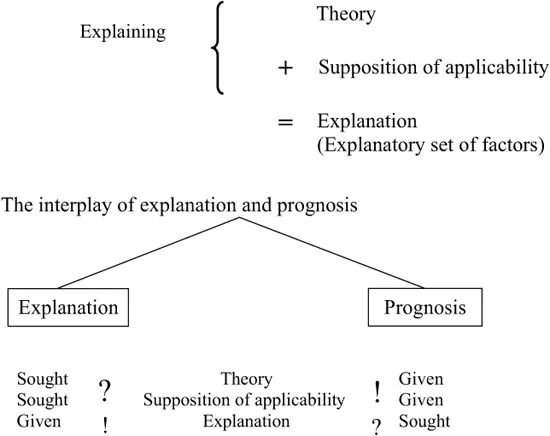

EXPLANATION

Whoever wants to learn from mistakes has to be able to explain things, and therefore must possess well-founded suppositions as to why an effect or set of facts has been arrived at, or why not.

1. In order arrive at an explanation an exact description of a problem is necessary, of its actual condition (for example, declining market share).

2. Then we look for theories (of a scientific kind, or resulting from experience), which perhaps can lend themselves to our problem (for example, “When our relative quality—in comparison to the competition—declines, we lose market share”).

3. Finally we check whether the suppositions of applicability of the theory at hand agree with our problem and its context (we come to the conclusion that the competitor has improved their quality, which entails a relative depreciation of our quality).

4. Having found a theory with valid suppositions of applicability, and thus having arrived at a possible explanation, it is normally advisable to look for alternative explanations (the competitor may simultaneously have expanded his product line and improved his market communication).

PROGNOSIS

The prognosis is an explanation “in advance”

1. We come up with a general plan (for example, improvement of quality) in connection with a particular goal.

2. If we want to predict the outcome of the plan, to possess well-founded suppositions as to whether we can attain our goal, then we need a theory with regard to the impact our plan will have (see above). Normally we will have come up with the above plan according to a known theory.

3. We can count on increasing market share unless further factors unknown to us come into play (future condition).

A second area of application for scientific insight is that of empirical examination; every empirical study is to be seen as an example of applied research (Irle, 1983, p. 25). This can be of use in the examination of a theory, of an explanation and/or prognosis of a problematic circumstance, and also in the development of new theories.

A particular quantity of elements coming into a relatively high (more than accidental) level of agreement with a theory is still not quite a satisfactory scientific explanation of why a particular resultant set of factors has been arrived at; this approach merely displays a meaningful character (Irle, 1983, p. 18). It is at least advisable to systematically rule out the possible relevance of other influences, which may be responsible for the designated factors rather than the theory currently being focused on.

Figure 1.2 The interplay of explanation and prognosis (see Raffée, 1995, p. 34)

Experimental or field experimental research is also scientifically relevant. In practice plausible models can occasionally suffice.

The evaluation of scientific insight in practice, the ultimate use of scientific research results, is usually brought out by applied science.

Market psychology is to a large degree oriented toward consumer markets and in that regard is almost exclusively focused on the behavior of consumers. Consumer psychology is as little reducible to buyer behavior as political psychology is to voter behavior (Irle, 1983, p. 12). It is certainly not just about an explanation and prognosis of buyer behavior. Behavior on the side of the provider is just as interesting, especially that of managers, who are responsible for the formation of programs designed to influence buyers. What hypotheses are they acting on? What assumptions concerning wishes and possibilities of influence do they hold? What information do they utilize and how do they come to decisions? The individuals engaged in practical marketing are by no means “scientists”, even if they like to see themselves as such. Market researchers, media researchers, working within practical marketing, are work professionals, not scientists. They evaluate scientific insights. Theirs is not a never-ending process of seeking after insights, but instead is oriented toward efficient goal attainment. As much as scientifically verified propositions influence their decisions, so does practical experience, including when such experience has not first been systematically checked. This is quite unscientific, but can however prove itself to be an adequate approach for solving practical problems that fall outside of scientific parameters. There is no reason to neglect practical experience or even to see it as inferior in value in comparison with scientific insights. Practical experience can prove very efficient; it is only that it has yet to be systematically checked. It is true though that some in the marketing field are inclined to noticeably augment their practical experiences with the addition of pseudo-scientific jargon, or to justify them with equally pseudo¬scientific explanations. This is a malapropism of practical experience. The interplay of the three levels of insight is illustrated in Figure 1.3.

In the following we will deal with a selection of theories that essentially have proven themselves not only within fundamental research but also within applied research, which we consider to be up to the task of elucidating market phenomena. In keeping with our broad concept of market psychology’s scope, the theoretical presentation will be supplemented with examples from many different subtopics of market psychology.

Theoretical Foundations

There is little doubt in economics concerning the idea that economies can be understood to be a goal oriented handling of limited resources, wherein decisions must be arrived at as to how to employ those limited resources. In the end economies facilitate the satisfaction of needs. Needs are subjectively experienced states of deficiency, existing in relation to the desire for satisfaction. In connection with buying, power needs become demands.

Contrary to the viewpoints of many economic schools, needs are not a given. They result from the interplay of supply and demand on the one hand and on the other hand from constantly shifting nets of social relationships, which likewise are not independent from product offers. “Attitudes, value orientation, convictions, and behavioral modes are to a large extent anchored in social relationships and social patterns” (Albert, 1998, p. 214). In their variability or stability they are dependent on the social milieus they are bound up with.

Figure 1.3 The interplay of fundamental research, applied research, and the solution of practical problems seen as evaluation of insights

Furthermore we are not starting from the premise that consumers behave “rationally” according to some clearly structured order of preferences. We are also assuming that this order of preferences, in turn, is not independent of product offers and equally influenced by social milieus. It is not clear how intrinsic of a role social grouping...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- About the Authors

- Preface

- Chapter 1 Market Psychology in the Context of Systematics

- Part I Cognition Theories

- Part II On the Development of Personality via Perception and on Through to Memory

- Part III Motivation and Emotion

- Part IV Power, Control, and Exchange

- Part V The Layperson as Psychologist, and the Search for Insight

- Part VI Case Studies in Market Psychology

- Index