eBook - ePub

Global Justice Movement

Cross-national and Transnational Perspectives

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Global Justice Movement

Cross-national and Transnational Perspectives

About this book

"Della Porta has assembled a distinguished group of scholars who have made great strides in illuminating the early phases of the movement. The book includes especially keen analyses of the movement against global capitalism, particularly in its European manifestations." John D. McCarthy, Pennsylvania State University "Della Porta has skillfully coordinated a comparative study in six European countries and the US. Renowned scholars give testimony of the movement in their countries. [This is] the first attempt to document a genuine transnational movement." Bert Klandermans, Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam You G-8, we 6 billion!" So went the chant at the international parade leading into the summit in Genoa, Italy. The global justice movement has led to a new wave of protest, building up transnational networks, inventing new strategies of action, constructing new images of democracy, and boldly asserting that "another world is possible". This book examines all this and more with case studies drawn from seven different countries, covering transnational networks and making cross-national comparisons. Leading European and American scholars analyze more than 300 organizations and 5,000 activists, looking at mobilizations that bridge old and new movements and bring politics back to the street. Contributors include: Massimiliano Andretta, Angel Calle, Helene Combes, Donatella della Porta, Nina Eggert, Marco Giugni, Jennifer Hadden, Manuel Jimenez, Raffaele Marchetti, Lorenzo Mosca, Mario Pianta, Herbert Reiter, Christopher Rootes, Dieter Rucht, Clare Saunders, Isabelle Sommier, Sidney Tarrow, Simon Teune, Mundo Yang.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Global Justice Movement by Donatella Della Porta,Massimiliano Andretta,Angel Calle,Helene Combes,Donatella Della Porta,Nina Eggert,Marco G. Giugni,Jennifer Hadden,Manuel Jimenez,Raffaele Marchetti in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

The Global Justice Movement

An Introduction

The Global Justice Movement in Context

When some fifty thousand demonstrators protested against the third World Trade Organization (WTO) conference in Seattle in November 1999, social scientists still focused on explaining the institutionalization of social movements. Only gradually did intense international mobilization—in counter-summits, Global Days of Action, European Marches against Unemployment, Intergalactic Meetings of the Zapatistas, and World Social Forums—start to build awareness of and interest in the emergence of a new cycle of protest. In subsequent years, hundreds of thousands marched against the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank meetings in Washington and Prague in 2000 and 2001 and against the European Union (EU) summits in Amsterdam in 1997, Nice in 2000, and Gothenburg in 2001. They protested the World Economic Forum in yearly demonstrations in Davos, the G8 summit in Genoa in 2001, and (following the call issued by the first European Social Forum) the Iraq war in hundreds of cities on February 15, 2003.

That cycles of protest emerge unexpectedly is certainly not new. On the eve of 1968, social scientists and politicians alike lamented the “end of ideologies,” the institutionalization of the labor movement and consumption society, and, above all, the decline of interest in politics. At the turn of the millennium, the debate focused on the disappearance of a sense of community, the institutionalization of the “new” social movement, the antipolitical stance of new generations. Surely, the emergence of a new cycle testifies to a rupture in the prevailing forms of collective action and organizational strategy as well as collective identities. In this sense, the perception of a sudden break reflects the challenges that cycles of protest pose to existing repertoires of collective action. During protest cycles, new organizational structures emerge with new styles of activism (Tarrow 1989; della Porta 2005a). What seemed established is once again in movement.

Waves of protest do not, however, emerge from nowhere. In the sociology of social movements, various concepts have been used to depict movement survival beyond protest mobilization: Melucci (1996) described the alternate stages of visibility and latency; Verta Taylor (1989) analyzed the functioning of organizations in periods of movement “doldrums.” It was observed that, even in low ebbs, social movement organizations do not invariably transform themselves into interest groups or charities (della Porta 2003a and 2003b). Social movement organizations from previous waves of mobilization often participate in the rise of new cycles of protest, ensuring continuity with the past.

Although often unexpected, the emergence of a protest cycle is not as sudden as it appears. Protest requires existing organizational structures able to mobilize resources, as well as less visible processes of networking and construction of justifications for collective action. It involves institutional actors and arenas: For instance, in some countries, the 1968 movements also developed inside student unions as well as in parties’ structures (Tarrow 1989). The emerging movements are often influenced by the characteristics of the organizations that “host” them in their infancy, and their evolution is the product of a mix of traditions and challenges to those traditions. The perception of a sudden rupture is in part an outcome of the natural conformism in the social sciences, where the confirmation of general trends (such as the bureaucratization of labor unions or the institutionalization of social movement organizations) is often facilitated by the choice of some objects of study (such as the union leadership or the more visible and better structured nongovernmental organizations [NGOs]) and not others. Conversely, the singling out of countertrends seems to be discouraged by their lack of visibility or relevance within the dominant paradigm.

In this volume, we pay attention to the way in which the protest on global justice developed, singling out the less visible steps of “remobilization,” as well as the innovations introduced in the action repertoires, structures, and frames during the protest cycle.

The protests we have just mentioned developed, as we will see, from a number of campaigns that networked existing organizations against the North American Free Trade Agreements (NAFTA); against the Multilateral Agreement on Investment; for the cancellation of poor countries’ foreign debt (in the Jubilee 2000 campaign); and for a more social Europe (in the European Marches against Unemployment and Exclusion).1 Within these campaigns, new frames of action developed, symbolically constructing a global self, but also producing structural effects in the form of new movement networks. After some preliminary experiences in the 1980s, counter-summits multiplied over the succeeding decade, simultaneous with large-scale UN Conferences (Pianta 2001b) and supported by frenetic Transnational Social Movement Organizations and NGO activity that claimed to represent not only their hundreds of thousands of members, but more generally the interests of millions of citizens without a public voice. Mobilizations at the transnational level have also been linked to (more traditional) local and national protests such as the mobilization of the “have-nots” in France, the anti-road protests in the UK, the labor action of critical, grassroots unions in Italy, and the environmental campaigns against large infrastructures in Spain. Local and national organizations interact transnationally, reacting to supranational institutions of governance, but they are also embedded in national traditions and opportunities.

Although the Global Justice Movement (GJM) acquired notoriety in Seattle, United States, it seems to have had a larger impact in Europe. Although September 11 and, especially, the Iraq war did in fact bring about a redomestication of activism in the United States (or, as Jennifer Hadden and Sidney Tarrow argue in their chapter, a process of internalization), in Europe transnational protest remains very dynamic. The process of the Europeanization of social movements not only intensified with the building of Europe-wide networks and campaigns, but is also spreading to Eastern Europe and Turkey.

On the Old Continent, the extraordinary capacity of transnational networking in the GJM is visible in the European Social Forum (ESF), the regional version of the World Social Forum, which provides an arena for encounters and debates to large numbers of organizations and activists from different countries. The first ESF, held in Florence in 2002, involved 60,000 participants—more than three times the expected number—taking part in the 30 plenary conferences, 160 seminars, and 180 workshops as well as 75 cultural events in various parts of the city. More than 20,000 delegates of 426 associations arrived from 105 countries, and about one million took part in the march that closed the forum. Although the number of registered participants declined in the two following meetings (about 40,000 in Paris in 2003 and 20,000 in London the succeeding year), the capacity of the events to involve activists from heterogeneous backgrounds and different countries remained high. The effects of increasingly broader networking were even more visible in the fourth ESF in Athens in May 2006, where not only did the number of registered participants again almost double (36,000), but the event attracted numerous delegations from Eastern Europe and the Mediterranean area.

Table 1.1 Opinions on the Global Justice Movement

Trust | Do Not Trust | Don’t Know/No Answer | |

France | 51% | 45% | 5% |

Italy | 33% | 64% | 3% |

Germany | 36% | 56% | 8% |

Spain | 47% | 42% | 11% |

United Kingdom | 41% | 49% | 10% |

Source: Adapted from “Flash Eurobarometer” on “Globalization” (2003).

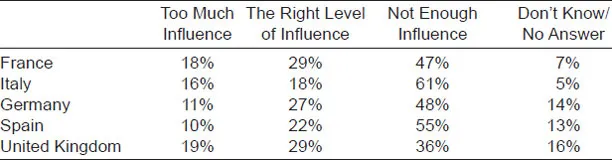

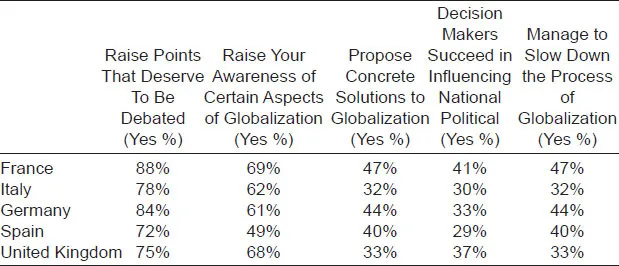

Additionally, if social movements are usually carriers of minoritarian challenges, the global justice movement seems to be an exception: According to a Eurobarometer Survey concluded in 2003, as many as 51 percent of citizens in France, 47 percent in Spain, 41 percent in the UK, 36 percent in Germany, and 33 percent in Italy claim to trust the movement (see table 1.1). In addition, many citizens think that the global justice movement should have more influence on the process of globalization: Sixty-one percent of respondents in Italy, 55 percent in Spain, 48 percent in Germany, 47 percent in France (but only 36 percent in the UK) state, in fact, that the global justice movement does not have enough influence on globalization (table 1.2). More than 70 percent of citizens in each country think that the global justice movement raises points that deserve to be debated; more than 60 percent (except for the Spanish: 49 percent) believe that it raises awareness of certain aspects of globalization, whereas between 47 percent (France) and 32 percent (Italy) think that it proposes concrete solutions to globalization (table 1.3). Additionally, between 41 percent (France) and 29 percent (Spain) believe that the global justice movement is successful in influencing national political decision makers, and more than 31 percent of citizens in all countries even see it as successful in slowing down the process of globalization.

Table 1.2 Opinions on the Global Justice Movement

Source: Adapted from “Flash Eurobarometer” on “Globalization” (2003).

Table 1.3 Opinions on the Global Justice Movement

Source: Adapted from “Flash Eurobarometer” on “Globalization” (2003).

Addressing the analysis of this cycle of protest at the turn of the millennium, we want to describe the emergence and evolution of the GJM, with its blending of tradition and innovation, national roots and cosmopolitan visions in six European countries, in the United States, and at the transnational level. As we will see, the mobilizations on global justice issues in France, Germany, Great Britain, Italy, Spain, and Switzerland, as well as in the United States, have much in common. Not only do they remobilize people on the street, but they also cast a broad net that covers organizations and groupings active on different issues and with heterogeneous initial concerns. They all focus attention on issues of global justice and “globalization from below.” They link local, national, and global issues, as well as local, national, and global organizational structures, mobilizing against a multilevel system of governance. If wide differences exist within each national context (with groups animated by moderate and radical repertoires and frames competing with each other), we also stress national specificities in our cross-national comparison—different densities in the networks of protest, different blends of protest repertoires, and different master frames—that are forged by national opportunities and movement traditions.

This chapter introduces this comparative endeavor by proposing, first of all, a definition of our object of analysis (section 2), and then by singling out common characteristics as well as different typologies in the movement networks (section 3), action strategies (section 4), and frames of action (section 5). Furthermore, we present some possible explanations for the emergence of the movement and its various national characteristics (section 6).

Defining the Global Justice Movement

This volume focuses on contemporary social movements, in particular on the mobilizations on issues of global justice and a “globalization from below.” The first question we want to address in this introduction refers to the definition of our object of research: the global justice movement. We can consider social movements as interactions of mainly informal networks based on common beliefs and solidarity, which mobilize on conflictual issues by frequent recourse to various forms of protest (della Porta and Diani 2006, chap. 1). In Sidney Tarrow’s definition (2001, 11), transnational social movements are “socially mobilised groups with constituents in at least two states, engaged in sustained contentious interactions with power-holders in at least one state other than their own, or against an international institution, or a multinational economic actor.” Global social movements can be defined as transnational networks of actors that define their causes as global and organize protest campaigns and other forms of action that target more than one state and/or international governmental organization (IGO).

Although these are all analytic definitions, useful for identifying abstract concepts, in our book we want to focus on an empirical actor, the global justice movement, which we define as the loose network of organizations (with varying degrees of formality and even including political parties) and other actors engaged in collective action of various kinds, on the basis of the shared goal of advancing the cause of justice (economic, social, political, and environmental) among and between peoples across the globe. This means that we focus on an empirical form of transnational activism, without implying that this covers all the existing manifestations of that abstract concept. We operationalize our definition by looking at collective identity, nonconventional action repertoires, and organizational networks.

A fundamental characteristic of a social movement is its ability to develop a common interpretation of reality able to nurture solidarity and collective identifications, as well as a collective attempt to change or resist changes in the external environment. Outside the political routine, the movements develop visions of the world alternative to the dominant ones. New conflicts emerge on new values. In particular, from the 1970s onward, “new social movements” began to be seen as actors in new conflicts, in contrast to the “old” workers’ movement that was by then perceived as not only institutionalized, but also focusing on materialistic issues. Gender difference, defense of the environment, and cohabitation among different cultures are some of the issues around which social movements have formed. The establishment of a global movement requires the development of a discourse that identifies both a common identity—the “us”—and the target of the protest—the “other”—at the transnational level. As far as the framing of the action is concerned, we are interested in those groups/individual activists who frame their action in terms of global identity and concerns: They identify themselves as part of a “global movement,” targeting “global enemies” within a global enjeu/field of action. Operationally, we focus on groups/activists that have been identified, in different countries, as alter-global, no global, new global, global justice, Globalisierungskritiker, altermondialists, globalizers from below, and so on. The individual chapters will discuss to which extent a common global concern spread during transnational protests.

Social movements are characterized by the use of protest as a means of pressure on institutions (e.g., Rucht 1994). Those who protest address the public even before they approach elected representatives or public bureaucracy. Just as protest actions were concentrated at the national level with the creation of the nation-state, globalization may be expected to generate protest at the transnational level against international actors. In our operational definition, we consider organizations and individuals who have participated in contentious actions organized by groups/activists with a global concern, as defined above. In parallel to past research that focused on those groups/actors taking part in protest activities, we look at organizations and individuals taking part in protest campaigns focusing on poverty in the South, taxation of capital, debt relief, fair trade, global rights, and reform of international intergovernmental organizations. In our contributions, we shall discuss to what extent mobilizations on these various issues have been linked in a common wave of protest.

Social movements are informal networks linking a plurality of individuals and groups, more or less structured from an organizational point of view. Whereas parties or pressure groups have somewhat well-defined organizational boundaries, with participation normally verified by a membership card, social movements are instead composed of loose, weakly linked networks of individuals who feel part of a collective effort. Although there are organizations that refer back to movements, movements are not organizations but rather nets, linking various actors who encompass (also but not only) organizations with a formal structure. One distinctive characteristic of a social movement is the possibility of belonging and feeling involved in collective action without necessarily being a member of a specific organization. It follows, therefore, that a global movement should involve organizational networks active in different countries. Operationally, with our focus on the global justice movement, we are interested in the individuals, groups, and organizations in each country that have built and/or participated in one or more networks on the global issues mentioned previously and acted via protest. Especially since we are dealing with movement(s) that address different specific issues (labor rights, genetically modified organisms [GMOs], women’s liberation, etc.), their belonging to networks that address these issues within global frames has a relevant, discriminating value. Participation in European social forums (or national/local social forums) and/or similar/parallel events or umbrella organizations is covered by our operational definition. In our research, we shall indeed address the role (frequency and importance) of participation in transnational events for local and national social movement organizations. The various chapters will discuss how dense the movement networks are in each of the analyzed countries and at the transnational level.

To summarize, we aim to analyze the presence of a social movement, defined by the presence of networks of individuals, groups, and organizations that, based on common beliefs and a collective identity, seek to change society (or resist such a change) mainly by the use of protest (Rucht 1994, 77; della Porta and Diani 1999, 16). We focus in particular on movement(s) as networks participating in protest campaigns on the issue of global justice. For our movement(s), the ultimate frame of reference is indeed the globe: Although specific actions often have a narrower scope, solutions are sought at the global level, and/or specific claims are embedded in visions of global change. Within these global dimensions, the main aim of the movement(s) is the struggle for justice—a general term that encompasses more specific domains of intervention such as human rights, citizens’ rights, social rights, peace, the environment, and similar concerns. Our empirical research will also address the issue of the degree of transnationalization in the movement discourse and the extent ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Acknowledgments

- Chapter 1 The Global Justice Movement: An Introduction

- Chapter 2 The Global Justice Movements: The Transnational Dimension

- Chapter 3 The Global Justice Movement in Italy

- Chapter 4 The Global Justice Movements in Spain

- Chapter 5 The Global Justice Movement in France

- Chapter 6 The Global Justice Movement in Great Britain

- Chapter 7 The Global Justice Movements in Germany

- Chapter 8 The Global Justice Movement in Switzerland

- Chapter 9 The Global Justice Movement in the United States since Seattle

- Chapter 10 The Global Justice Movement in Context

- References

- Index

- About the Contributors