- 328 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

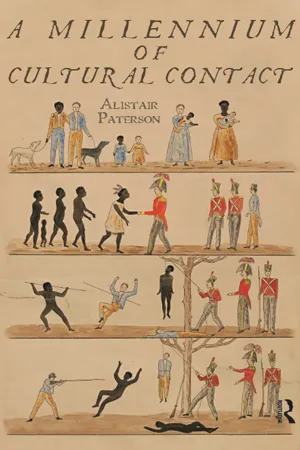

A Millennium of Cultural Contact

About this book

Alistair Paterson has written a comprehensive textbook detailing the millennium of cultural contact between European societies and those of the rest of the world. Beginning with the Norse intersection with indigenous peoples of Greenland, Paterson uses case studies and regional overviews to describe the various patterns by which European groups influenced, overcame, and were resisted by the populations of Africa, the Americas, East Asia, Oceania, and Australia. Based largely on the evidence of archaeology, he is able to detail the unique interactions at many specific points of contact and display the wide variations in exploration, conquest, colonization, avoidance, and resistance at various spots around the globe. Paterson's broad, student-friendly treatment of the history and archaeology of the last millennium will be useful for courses in historical archaeology, world history, and social change.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Millennium of Cultural Contact by Alistair Paterson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

THE WORLD AFTER AD 1000

Even for an archaeologist, a millennium seems vast. Only fourteen generations of seventy years stacked end to end separate us today from AD 1000, yet the world around a thousand years ago was very different from the global community of which we are a part of today.1 The lives of our ancestors of that time were more similar to our very distant relatives in preceding millennia than to ours. Although Europe was a relative backwater, it is where, in coming centuries, momentous events were to occur which would form the basis for our modern world. Voyages, discoveries, and cross-cultural encounters would transform humanity’s understanding of the world and its occupants.

At the heart of this millennium were billions of encounters between individuals of different cultures—that is what this book is about. The descendants of these encounters have many legitimate questions about these events, as do historians, archaeologists, anthropologists, geographers, biologists, and theologians—the list is long. What do we know about past culture contact in this period? How do we know about it? What types of encounters occurred? How do we understand the results of these events, since most of them occurred beyond the chroniclers of history?

These are relevant questions to us today for two reasons. First, many believe (I am one, Henry Ford was not) we can learn from the past to act properly in the present. Second, the legacy of these events remains with us today in the form of the great human accomplishments as well as the great inequalities and injustices that make the second millennium the greatest millennium of culture contact.

One thousand years ago, there was no global community as we understand it today. The sun rose over an extensively peopled world, but its population was probably only half a billion. On 1 January AD 1000, in jungle, desert, and tundra, in farms, villages, and cities, humanity awoke to the day ahead. People traveled over land and water to explore, trade, and migrate. Farmers went to their animals and their plants to tend them in the constant cycle of husbandry, pushing individual species of plants and animals along their own journeys of gradual change. Most of our modern diet had been domesticated—except some later domesticates like strawberry. Most people were farmers, yet hunters and foragers were to be found everywhere—in far greater numbers and landscapes than today—and they too began their day with the individual and group responsibilities that ensured everyone’s survival.

The great difference between 1000 and today was the level of knowledge individuals held of the other humans with whom they shared a planet. Most humans, probably all humans, were connected to other people, beginning with their neighbors and then beyond to more distant and unfamiliar places. Travelers, traders, slaves, migrants, and refugees ensured that people were always aware of distant places. Written or oral histories were common to most people; these provided a catalog of each community’s knowledge of others. But essentially, the world was far more dissected and compartmentalized than it is today and was broken up into regional networks.

Some networks were massive, extending over oceans and continents, such as the network of Arctic communities across the North American Arctic through to Greenland. Maritime networks linked Asian and African trading communities through the heart of the Indian Ocean. The main overland link across Asia was the Silk Road, joining West Asia and India with China through hubs of long-distance commerce across Central Asia, while ships sailed to Southeast Asia, known to Arab seafarers as “the land below the wind.”

Barriers between these geographical compartments—best envisaged at an island, continental, or ocean level—effectively restricted the movement of species, including those with whom humans had developed symbiotic relationships. Accordingly, the ancient soils of Australia had yet to feel a hoof, America had no large beasts of burden, and the islands of Polynesia were in the process of adjusting to the recent introduction of the Polynesian “trinity” of dog, pig, and chicken, along with garden crops. The great reworking of species globally after 1492, known as the “Columbian Exchange,” lay a few centuries in the future.2

Today we mainly live in urban societies, while in 1000 people lived closer to primary food production or food gathering. Cities existed, some of the largest being in Asia (in China, Chang’an, modern Xian, had reached a population of one million), while in Mexico, Teotihuacan, near modern Mexico City, reached 100,000. Work by Khmer hydraulic engineers was underway at Angkor Wat in Cambodia that would see it become the world’s largest urban center within a century. Large cities in West Asia were Baghdad (perhaps 500,000) and Constantinople (now Istanbul, 400,000), while Córdoba in Spain and Cairo in Egypt were also large.

Yet, many of today’s large cities were small communities of a few thousand people. Some, like New York, did not exist. Few of the large urban centers were in Europe.

A millennium ago, the sunrise over North and South America lit places undreamed of by the rest of the planet—these places would, after 1492, become a “New World.” This is despite America’s having already entered European networks of knowledge, trade, and communication with the arrival of Vikings there at the very end of the first millennium.

The people of the New World were diverse, extending from the Arctic realms to the tip of Tierra del Fuego. Hunters and foragers occupied many environments, from the very cold regions to tropical jungles. Hunting was part of most native peoples’ lives, as hunted foods contributed to many peoples’ quest for food, whether they were farmers or not. Farming was prevalent in many regions, built on millennia of independent domestication in several places in the Americas (the Eastern Woodlands, Mexico, and South America), and by this time farmers were successful with their maize, bean, and squash triumvirate, with potato and other crops significant in South America.

Shifts toward more complicated and hierarchical societies, as well as village and urban forms of settlement, had occurred in many parts of the Americas over preceding millennia. In the woodlands of eastern North America, along the Mississippi River’s course, this was the time of the Mississippian cultures, also to become known as “mound builders” after their earth and wooden monuments. These farming communities would come to trade widely and to build urban regional centers, the largest known being Cahokia (near modern St. Louis).

In Mesoamerica, complex societies had been rising and falling for thousands of years, and the ruins of Teotihuacan, Moche, and Chavín cultures were a familiar part of the landscape (just like ancient monuments stood over Cairo, Rome, and Baghdad). One thousand years ago, the Mayans were in a slow decline—Tikal already lay abandoned for over a century; however, other major Mayan settlements like Chichén Itzá and Tula remained vibrant, yet would also be abandoned. The rise of the Aztecs in central Mexico lay in the future, as did their momentous encounters with the Spanish conquistadors. However, these futures were still undreamed of.

A millennium ago in Mesoamerica, characteristic aspects of state societies were to be found: urban communities; writing; grand architecture; elaborate social and political structures; and specialization of artists, craftworkers, engineers, and others. Despite these complex communities, most people were farmers and were required to provide some of their output to the aristocratic rulers and their entourage.

Similar complexity existed in South America, where for thousands of years many small and larger states had flourished: a millennium ago, Andean centers of the Tiwanaku, Huari, and Chimú were significant complex societies, and in many ways the predecessors of the Inca Empire of the 1400s.

In summary, the millions of Native Americans in 1000 lived amid great diversity. Many lived in permanent villages of farmers, while in some resource-rich locations like modern British Columbia, year-round villages of intensive food collectors existed without requiring farming. There also were small and large urban settlements. Many of the staples of our world were growing in American gardens and fields: tobacco, tomato, corn, coca, and coffee. These would not be known of by the rest of the globe for many centuries to come. (It seems incredible to imagine Italian cuisine without tomatoes, beans, polenta, espresso, or indeed tobacco!)

Across the Americas, there was no knowledge of the other continents, despite possible contacts between Polynesians and some coastal South American peoples, suggested by the Polynesian people’s use of sweet potato, an American domesticate. Additionally, in the far Northwest, people of the Bering Strait probably maintained contacts across the Arctic world.

As we follow the sunrise westward, the Pacific Ocean world meets the new millennium. The islands of Oceania, too, were utterly outside European knowledge—this was another “New World” in the wings. The more remote corners of this massive oceanic region were still in the process of being discovered at 1000; the colonization of New Zealand (Maori: Aotearoa) and neighboring islands still lay centuries ahead.3 Islands such as the Society Islands, Hawaii, the Marquesas, and the Cook Islands were newly populated by people with a shared Polynesian heritage, with links back toward distant relations in Fiji, Tonga, and Samoa.

When Europeans arrived in Polynesia, they would marvel at the massive geographical spread of Polynesian societies. The Polynesian elite man Tupaiai who joined Captain James Cook’s crew in April 1769 profoundly demonstrated these links by being able to communicate with disparate Polynesians whom Cook met, as far distant as the Maori in New Zealand. In fact, this instance of culture contact brought together two great maritime navigators: the renowned Captain Cook and Tupaiai, who produced a map of Polynesian navigational knowledge covering 2,500 miles of ocean!

Pacific people had specialized to life on diverse islands, some large and relatively resource-rich as compared with small islands like atolls. Humans tended to rely heavily on gardening, marine resources, and introduced animals such as rat, pig, chicken, and dog. Societies varied in complexity; however, in certain islands in Micronesia and Polynesia, stratified societies with specialization of trades and careers developed, matched by great efforts of terra-forming and monumental construction, most popularly known today in the stone heads of Easter Island (Rapa Nui). These were a continuation of established Polynesian practices, albeit grown large.

Expert navigators and boat builders maintained links between islands, such as in the Kingdom of Tonga, or among the disparate Caroline islands of Micronesia; these were maritime empires based on trade with neighbors.

Farther west, in Near Oceania, people of Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, and New Caledonia were descended from the ancient colonists of the region who came millennia earlier: Asian farmers, known as Lapita people, after the archaeological site of Lapita in New Caledonia where their distinctive and widespread pottery with human face decorations was first found, as well as from the Pleistocene populations who first reached the Pacific islands at least 40,000 years ago.

Consequently, a diverse range of farmers and hunter-foragers filled Melanesian islands. In the highlands of Papua New Guinea (PNG), an independent shift to gardening had occurred thousands of years earlier, and a vast population existed in these isolated mountain valleys. These would be some of the last indigenous populations on earth “discovered” by Europeans. First contact in the “highlands” of PNG occurred in the 1930s when Australian gold prospectors led expeditions into the mountainous inland.

The continent of Australia, like the Americas, lay outside the knowledge of Europeans at the millennium. The diverse Australian environment—from the tropics of the north to the cold climate of the island of Tasmania—sustained societies of hunter-foragers with expertise in landscape management, most dramatically through the use of fire.

People had arrived in Australia at least 50,000 years ago and quickly colonized the corners of the continent. Later, contact with people in Southeast Asia occurred during the Holocene, when the dog (dingo) was introduced. Yet, in 1000, sustained contacts with Asian traders lay centuries ahead, as did the arrival of Europeans. Australia would be the last inhabited continent discovered in the European “Age of Discoveries.”

Island Southeast Asia at 1000 was characterized by great diversity, from hunter-foragers of Borneo to the religious states on islands like Java. These islands were all in contact, often mercantile in nature, and linked to continental Asia, where great religions and states had long been established. In East Asia, Hinduism and Buddhism, as well as Taoism, Confucism, and animism, were all significant. While not influential east of the Indus River until after 1000, Islam would eventually become significant in southern Asia and China, as well as in Indonesia, today the largest Muslim nation in the world.

The key regional power in Asia at 1000, as today, was China. The Song Dynasty controlled a society as advanced as, or perhaps more advanced than, any found anywhere else. While ancient trade routes enabled a trickle of trade from China to the west, Europeans knew little directly of Asians, except those of West Asia.

Trade across Asia was built on long-lasting connections. The main movement of goods at that time out of Canton was in Arab vessels, or through seafarers in the southern China seas. It would be centuries before Europeans followed the trade routes over Central Asia to meet the Chinese, although a thousand years earlier the Chinese and Roman civilizations had been in contact through trade.

As the regional superpower, China strongly influenced its neighbors in Korea, Japan, and Vietnam. Disturbance to this situation seemed impossible: the years of Mongol control of China lay centuries ahead at this time.

Key Hindu Asian states were in Java and in Cambodia with the Khmer Empire, although the development of Angkor Wat, a massive medieval-era urban settlement based on a massive water management network, lay a century ahead. This low-density settlement would cover nearly 3,000 square kilometers—the world’s largest preindustrial urban settlement. Yet, the vigorous jungle would claim the city back in its decline: Angkor Wat was abandoned by the time the French discovered its ruins many centuries later.4

In 1000, a stable civilization in Japan under an aristocratic government was adjusting to new developments, such as the advance of script to write Japanese with freedom, and the rise of samurai in rural provinces. The “opening up” of Japan by European powers lay many centuries ahead.

In India, the ancient cities of the Indus valleys lay long abandoned—at 1000, the sequence of kingdoms that characterized southern Asia were about to see the establishment of a series of Muslim states in the northwest. Along the coast, active trade ports allowed local and Arab traders access to the products of South Asia.

West Asia had for millennia been the setting for various human “firsts”: from farming to writing. The region was the very center of the Old World: the coffee table around which Asia, Africa, and Europe sat. This was a great time for the Islamic civilization, itself made up of many different cultures in contact through a common ideology. The height of the Islamic world at 1000 extended from the western Mediterranean regions of the Iberian Peninsula, across northern Africa, the Gulf of Arabia, and to the Indus River. This vast region was linked by trade routes. The maritime route via the Persian Gulf had allowed Islamic merchants to be active from India, Sri Lanka, and the Southeast Asia archipelago, and in East Asia. Shipping routes extended from Zanzibar to Java. Other goods moved overland via the ancient trade routes.

In 1000, the Eurasian trade network was similar to that formed in the Roman era, with trading ports in the eastern Mediterranean as intercontinental depots for the movement of goods between Africa, Asia, and Europe. Trade relationships would change dramatically at the end of the medieval period, when European powers would take over much of the trade from the Italian merchants in the Mediterranean, and from the Arabs, Asian, Chinese, and Gujerati traders in the Indian Ocean and Southeast Asia.

Constantinople and Baghdad were key cities in West Asia, one Christian, the other Islamic. In the Muslim world, the arts and sciences were encouraged, and key developments occurred in astronomy, mathematics, literature, and philosophy. These would soon be important in the revitalization of Europe. Constantinople would also protect older knowledge, in its role as the eastern center of the Holy Roman Empire.

Trade networks linked the Islamic world not only to Asia but to Africa. Arab traders were active along the east coast of Africa and in West Africa. In Africa, the trans-Saharan trade route moved goods—such as gold, slaves, and salt—across the Saharan barrier to North African ports such as Tangier, Algiers, Tunis, and Alexandria, all of which had long been significant locations for trade and interregional contacts. Islam thus spread to West Africa through trade.

East Africa too became enfolded in trade networks managed by Muslims. In East Africa, trade societies, such as that of the Swahili, merged African, Arabic, and Indian influences.

In central and southern Africa, culture contacts were occurring along a broad front, as people were on the move. For example, Bantu people were moving their herds south, coming into contact with hunter-foragers, many of whom would still be ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

- PREFACE

- CHAPTER 1. The World after AD 1000

- CHAPTER 2. Our Attempts to Understand Culture Contact

- CHAPTER 3. Encounters in the Northwest Atlantic

- CHAPTER 4. Europe and Its Neighbors

- CHAPTER 5. Sub-Saharan Africa

- CHAPTER 6. The Spanish in the Americas

- CHAPTER 7. North America

- CHAPTER 8. East Asia and Oceania

- CHAPTER 9. Australia

- CHAPTER 10. Millennium

- NOTES

- REFERENCES

- INDEX

- ABOUT THE AUTHOR