- 178 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Educating Children and Young People with Acquired Brain Injury

About this book

Educating Children with Acquired Brain Injury is an authoritative resource book on the effects of brain injury on young people and how educators can understand and support their needs. This new edition has been updated to reflect changes to legislation and practice relating to special educational needs and will enable you to maximise the learning opportunities for young people with acquired brain injury (ABI). Considering key areas in special educational needs such as communication, interaction, cognition, sensory and physical needs, the book provides information on the multifaceted needs of children and young people with ABI and how these needs can be met.

This book will help you to:

- Understand the difficulties that young people with ABI experience

- Support these students by using appropriate strategies to help their learning

- Understand and address the social and emotional difficulties experienced by these students

- Work in partnership with families and other professionals

- Understand information from other professionals by reference to a glossary of terms

- Access further useful information from relevant resources and organisations

Written for SENCOs, teachers, teaching assistants, educational psychologists and other education professionals across all settings, Educating Children with Acquired Brain Injury is full of useful information and advice for parents and other family members, clinical and behavioural psychologists, therapists and support workers involved with children and young people with ABI.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Chapter 1

Understanding the developing brain

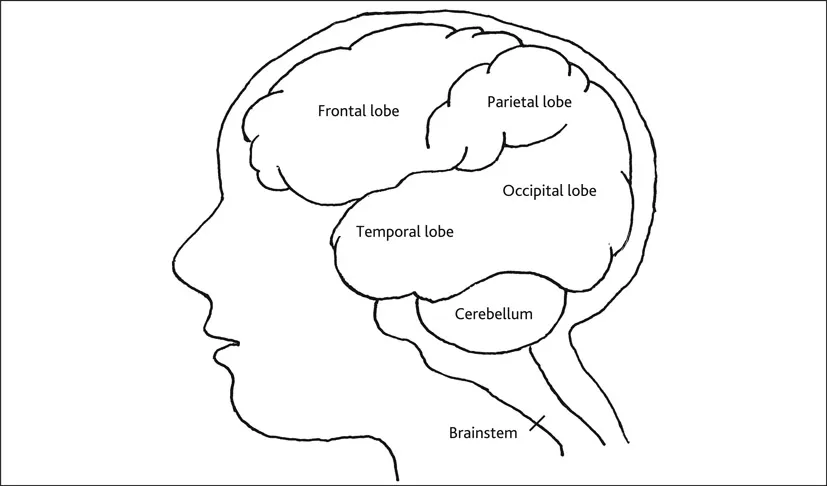

Structure of the brain

- Occipital lobes, at the very back of the head, are involved in processing visual information. This includes visual acuity – often just termed ‘vision’ – and the way visual information is interpreted, e.g. colour, word or object recognition.

- Parietal lobes are located at the back and top of the head, behind the frontal lobes and above the temporal lobes. They are responsible for the processing of information about body sensation – touch, pressure, temperature and pain – as well as the integration of visual and auditory information and an understanding of spatial relationships.

- Temporal lobes are located under the temples and are important for hearing and many aspects of memory. They are crucially involved in certain processes relating to attention and language, to musical ability, and to facial and other aspects of visual recognition. An area of the brain called Wernicke’s Area spans the temporal and parietal lobes and is partly responsible for our understanding and production of language. Deep within each temporal lobe is also a structure called the hippocampus – named thus as its shape is said to resemble a seahorse. This plays an important role in memory and is linked with other areas involved with emotion.

- Frontal lobes are located behind the forehead. They are relatively immature during childhood and develop over an extended period into early adulthood. They are extremely vulnerable to injury because of their location at the front of the head (McAllister 2011). The frontal lobes are responsible for some motor functions and some aspects of memory but are particularly important in respect of ability in problem solving, initiation, judgement, impulse control, etc. They act as ‘behavioural regulators’, planning and evaluating behavioural responses. These, along with other behaviours, are known as ‘executive functions’ (see Chapter 4). The frontal lobes also contain a structure known as Broca’s Area that is associated with our ability to speak and also, to some extent, to understand language (Caplan 2006).

Protection of the brain

- Skull or cranium: This is the hard bone that surrounds the brain and generally serves to protect it. However, the inner surface of the skull has some bony ridges – most particularly in the frontal area – which can result in damage to the soft brain tissue if shaken against it.

- Meninges: The brain is covered by three layers of membrane, known collectively as the meninges. The outer one, called the dura, is like a very tough plastic sheet and protects the brain from movement, but not if this is excessive or violent. The two inner layers are more delicate.

- Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF): CSF is a clear watery-like liquid that surrounds and cushions the brain. It circulates throughout four hollow chambers within the brain called ventricles and around the brain and spinal cord, acting like a shock absorber. CSF also removes brain waste products and provides the brain with nutrients. New CSF is constantly being produced while old fluid is released and absorbed into blood vessels.

- Blood: Blood provides oxygen and nutrients for the brain; a blood-brain barrier filters the blood and provides some, but not complete, protection to the brain from any chemicals in the blood that could be toxic.

Brain development

Growth before birth

Growth after birth

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1 Understanding the developing brain

- 2 What happens in brain injury?

- 3 Why does ABI provoke different special educational needs?

- 4 Most common areas of difficulty provoked by ABI

- 5 Planning school and college integration or reintegration

- 6 Assessment of children and young people with ABI

- 7 Understanding and supporting behaviour changes

- 8 Social supports

- 9 Planning educational provision

- 10 Classroom strategies

- 11 Transitions

- 12 Working with families

- 13 Mild traumatic brain injury (and sports concussion)

- Useful organisations and resources

- Glossary

- Index