- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Corporate Strategy in the Age of Responsibility

About this book

As the era of ever expanding markets and ample resources ends, governments and business will have to behave differently. The world is facing weak economic growth, limits to affordable resources and increasing concerns about environmental consequences. During the boom times, governments championed de-regulation and business responded by adopting an anything-goes attitude. In these straitened times, strategic analysis has to engage with the challenges that society faces to create resilient corporations fit for the 21st century. In Corporate Strategy in the Age of Responsibility, Peter McManners, who has for nine years run strategy workshops on the Henley MBA focusing on the global business environment, sets about providing a strategic framework for navigating the new economic environment. Chief Sustainability Officers (CSOs) now exist, but they struggle to find the strategic rationale for the improvements they champion. The author argues that their good intentions often lack traction, partly because others in management don't get it, but also because they are not ambitious enough. The book is not about preaching semi-charitable behaviour or how to enhance the reputation of the corporation instead it is about surviving and thriving in a challenging and changing environment. A corporate audience familiar with strategy books will relate to this book, but will find it steers them towards radically new strategic thinking suitable for a turbulent period of transition.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Corporate Strategy in the Age of Responsibility by Peter McManners in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

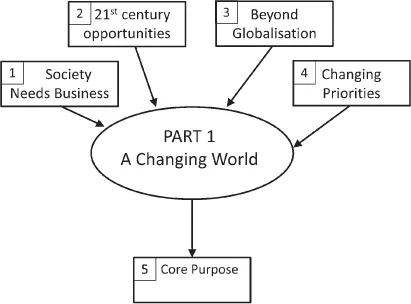

PART I

A CHANGING WORLD

‘Management will remain a basic and dominant institution perhaps as long as Western civilization itself survives’

Peter Drucker 1955

The corporation does not stand alone but operates within the wider economy exposed to the demands and expectations of society. As the world changes, business must adapt; and business adapts by adopting a new strategic direction. Understanding the changing world in sufficient (but not overwhelming) detail is a fundamental foundation of the strategy formulation process.

The twentieth century saw the emergence of ‘management’ as a distinct academic discipline and leading institution in industrial and civic society. The influence that management has had – and continues to have – over the direction of society is considerable. The influential management guru Peter Drucker wrote the words above at the time when the first business schools were established with optimism that management would remain a positive force at the heart of Western civilization (Drucker 2007). His view echoes the words of Jonathan Swift three hundred years ago, ‘whoever could make two ears of corn, or two blades of grass, to grow upon a spot of ground where only one grew before, [does]… more essential service to his country, than the whole race of politicians put together.’ (Swift 1726:223)

In the twenty-first century, corporations have to live up to the aspiration of management as a basic and dominant institution in Western civilization. The world today is subject to huge conflicting pressures as the economy falters and resource limits are reached. This comes at a time when highly populous countries such as India and China aspire to much higher standards of living starting from a very low base. The pressure on resource will be intense. Society is facing an impending crisis but most people have not yet woken up to the enormity of the challenge. Leaders in business and organizations across society need to adapt and embrace new strategic thinking as society and the economy are reconfigured to altered circumstances. The world is at the beginning of a period of massive change and corporate strategy has to move in-step or be left behind. The companies that embrace the emerging new reality have a wealth of opportunities to exploit. Before embarking on a strategic analysis, it is worth climbing up to a high point and looking out across society and the economy to get a feel for the lie of the land and reconsider the core purpose of the corporation.

Figure PI.1 Structure Part I

CHAPTER 1

SOCIETY NEEDS BUSINESS

The role of business is as an integral part of society and the economy.

With hindsight, we will look back at the current era and wonder how we can have been so blind to the real world around us; so locked in denial of the need for a new direction; and so completely unable to make the changes required. Each person lives their life within the limits of the possibilities open to them constrained by the bigger picture of society and the economy. Business is similarly constrained, but of all the actors in society, business is the most capable of throwing off the shackles and driving forward the process of change. Society needs business now, more than ever, to take a leading role. If business can show it can be trusted, society will give business permission to operate in new and dramatically different ways. No one should ask, or expect, corporations to become charitable organizations, replacing the profit motive with altruistic intentions, but corporate leaders need the inspiration and freedom to find a new direction for the twenty-first-century corporation. The driver for corporations always has been, and should continue to be, commercial success. Chief executives and senior executives need to take off their blinkers and open their eyes to the emerging new reality. There is a world of commercial opportunities ready to be exploited if business can adapt strategy to address the challenges of our time.

THE ROLE OF BUSINESS

The role of business would seem to be obvious until attempts are made to define it. Does business deliver products and services? Does business provide employment? Does business provide a return to shareholders? Can business do all of this and more? Wherever there is an activity that can be carried out profitably, business will be there, but a generic description of the role of business is elusive.

One starting point is to define what business is not; business is not the government and business is not a charity. Business is not responsible for deciding what is right for society and does not have to step in to cure the ills of society. Perhaps business is simply a mechanism to make money. Is the definition of a successful business a collection of activities which pays out more than you put in? On this basis, a Ponzi1 scheme would be a good business up to the point where it implodes. Clearly this is not right; business has to have a future that goes beyond an immediate profit. What of a business that delivers a financial profit but causes damage to society or the environment? This would fit the definition of a money-making machine but common sense tells us that this is wrong; such a business is unlikely to last and is at risk of being shut down.

A definition that gets close to capturing the essence of business is:

Business is a collection of activities that together fills a role in the economy that is needed by society, which operates within the safe bounds of the environment, and delivers a return to its shareholders.

This definition appears closer to reality than the idea of business as a money-making machine but this is starting to encroach on areas which are the responsibility of government and overlap with the interest of charitable organizations. We have already decided that business is not governmental or charitable so what is going on?

Business is the universal agent within the capitalist economy. Proponents of free-market capitalism argue that government should get out of the way. Business will arise wherever there is a need; expand and grow where there is demand; and contract and die when the service is no longer needed or is replaced by something better. This philosophy requires government to step back and give business the freedom to operate with the minimum of interference and minimum regulation. Where business uses its freedom responsibly, society is content to renew its licence to operate. However, where business falls into the trap of regarding its activities as little more than making money, the government is forced to step in to legislate. The battle between money-making machines on one side and legislators on the other leads to ever more red tape as the legislator is always one step behind the machine operators. Money-machine-operator mentality kept in line by regulators closing loopholes is no way to manage the primary agents of capitalism.

The role of business is as an integral part of society and the economy. Its freedom to operate correlates directly with the responsibility of its performance. A free license to operate is better for business and more responsive to the needs of society but is only granted where business can demonstrate responsible behaviour.

BUSINESS AND SOCIETY

The main actors in society are government, business and a collection of not-for-profit organizations which can be referred to as the ‘third sector’. These have different abilities and priorities. The most capable is business, being very good at spotting the opportunities, assessing the risk and mobilizing capital to get things done. Government is the most powerful, operating under the overarching objective of making life better for its people. The third sector fills gaps, operating in a variety of ways depending on the organization’s charitable objectives. Business is less constrained than either government or organizations in the third sector but it is argued here that business should also have a clear purpose to fit the niche it occupies in the economy. Those who argue a different case, that the purpose of business is simply to make money for its shareholders, underplay the potential of business to be an agent for change and risk damage to both business and society.

For business, it is important to realize that its activities are integral to and inseparable from society; business delivers the products and services on which people rely, provides employment and acts as a home for people’s long-term savings. The huge breadth and reach of business provides considerable power and influence over the direction of society, but generally this is not a power that is harnessed towards any higher purpose than for each business to succeed as best it can.

For society’s savings, it is generally acknowledged that investing in equities is the best long-term investment because business is good at putting capital to work to earn a profit. This means that a large proportion of the investments held by pension funds and fund managers is held in equities. The owners of these investments (everyone) have, in theory, huge power over business but this is generally not exercised except to the extent of moving money around to where it will generate the highest return.

Business has huge latent power over society and society has huge dormant power over business but both parties have been persuaded to distance themselves from each other using the maxim of shareholder value. Instead of a direct control relationship between the owners and the corporation, shareholder value is used as the basis of the relationship. This concept is the bedrock of most finance modules on MBA programmes. Those going into management are taught to focus on delivering shareholder value; those who become investment managers are encouraged to focus on measures of shareholder value when deciding how to invest. Management focused on financial results and investors focused on financial return, pares away at the notion that there can be other objectives and other values. This dysfunctional arrangement has set business on a disorganized frenzy of profit building to no better purpose than playing a slot machine. As corporations improve their ability to deliver shareholder value, they can become ever more divorced from society unless management spot the dangers and realise that shareholder value is a very narrow measure and must be used with caution.

To achieve sustained success, a business has to have a clearly defined role in society which is greater than the basic requirement to deliver a return to shareholders. It is a sad reflection on the current state of management thinking that it is necessary to restate this truism but without such foundations the corporation is bound to fail, sooner or later. The strategic process should support finding a place for the corporation that cements its place in society.

THE AGE OF RESPONSIBILITY

Governments have responsibility for the cohesion and success of the society to which they answer. They face some huge challenges ranging from climate change and the end of the era of fossil fuel to the problem of resource limits and creating jobs in an increasingly automated world. These problems require solutions and finding them is becoming urgent.

The current version of laissez-faire capitalism is not providing solutions; it is not even providing the possibility that there could be solutions. A system has arisen in which democratic governments are powerless to force through the degree of change required. Business may not be the cause of the problems but business is also not part of the solution, with little sign of systemic change to align business with the real needs of society.

Business has put its licence to operate at risk through behaviour which invites questioning the legitimacy of the model of corporate capitalism. Three examples will be used to illustrate the problem. These are not extreme examples of corporate wrongdoing, such as the massive fraud perpetrated by Enron executives revealed in 2001, but common-place examples of legal corporate behaviour. First under the responsibility spotlight are the tax affairs of the large multinational corporations Google and Starbucks. In 2013, it was reported widely in the media that these corporations had been using loopholes in tax law to manipulate their accounts to avoid paying tax in the UK. They defended their actions by claiming that they have a duty to maximize returns for their shareholders – to the maximum extent allowed by law. This corporate attitude challenges the government to close such loopholes and add yet more red tape. Gaming the tax system in this way leads to ever more complex rules and regulations providing a strait jacket for corporations in a wasteful merry-go-round of tax avoidance advisors against tax officials. This blatant tax avoidance by a Multinational Corporation (MNC) at the expense of the public purse is an unambiguous example where the case for more responsible behaviour is easy to understand. Other situations may not be so clear cut.

The second example is more nuanced and comes from the oil industry’s strategic approach to the exploitation of unconventional oil. The context of the example is in a risky industry where accidents happen. The oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010 was the sort of accident which may have happened eventually drilling for oil pushed at the limits of technology in deep water. In this case, there were human errors and blame was laid on BP and its contractors. Every employee is fallible so mistakes will occur and there will be accidents, but what of the strategic decision to exploit unconventional oil such as the oil sands of Athabasca in Canada? This will involve not only environmental damage to excavate the oil sand but also energy-hungry processes required to separate the oil from the sand; unconventional oil is therefore a dirty high-carbon fuel compared with conventional oil. The pollution and environmental damage will not be an accident but a consequence of deliberate strategy. While society fails to deal with climate change and fossil fuel dependency, no law will have been broken. The question arises, should corporations exploit the inability of government to take action to close the fossil fuel economy or start to work with government on the challenges of closing it down? This example is typical of the dilemmas that corporations face.

The third example is Southern Cross, a provider of care homes for old people operating in the UK, which was acquired by the American private equity group Blackstone Capital Partners in 2004. This was the start of a buying spree in which Blackstone added Nursing Home Properties (NHP) the same year and Ashbourne Group care homes in 2005. By the end of 2005, Blackstone had built one of the largest portfolios of care homes in Britain financed mainly by debt (Sabbagh 2006). Blackstone reorganized the business under a sale-and-leaseback strategy placing the ownership of the properties in Nursing Home Properties (NHP). Blackstone then prepared NHP for sale as a property company and Southern Cross as a care home operating company. NHP was sold in 2006 for over £1.1 billion at a time when property investments were in demand and Southern Cross was floated on the stock market the same year. It is estimated that Blackstone banked a profit of up to £1bn on its investment (Ruddick 2011). However after the sale, Southern Cross was left with a debt burden and lease responsibilities which proved to be unsustainable in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, leading to collapse in 2011. Blackstone argued strongly that they sold a sound business and it was the subsequent management of Southern Cross that caused its collapse (Blackstone 2011). Whoever was to blame, there was much concern among charities and the Government about the plight of Southern Cross’s 31,000 residents caught in a game of corporate financial engineering. Anger was aimed at the company’s former owner, private equity group Blackstone who did nothing illegal, but if this is the behaviour of the agents of capitalism there is no wonder that trust in business has evaporated.

These three examples show how business focussed solely on generating cash is not the way that corporations endear themselves to society and is not how they should fit into the fabric of society. Blatant tax avoidance, strategies that conflict with key government challenges and financial engineering at the expense of vulnerable stakeholders are not the methods of responsible corporate strategy.

The general view that has dominated policy for the last two decades is that free-market capitalism is to be defended, warts and all, for the benefits it brings. These three examples could be written off as unfortunate but ultimately small-scale failures but it is argued here that such examples are now common and show that blinkered adherence to market fundamentalism is no longer justifiable. The voices of dissent are expanding beyond anti-capitalist campaigners to include moderate people taking a sensible pragmatic view that if this is capitalism, it must be reformed (Tormey 2012). In the age of responsibility, government and society will demand that business finds a new sense of responsibility or the licence to operate will be withdrawn and replaced with a straitjacket of red tape squeezing the life out of the corporation.

THE EMERGING BUSINESS LANDSCAPE

The leaders of corporations are some of the most forceful, dynamic and ambitious people on the planet; they have to be to survive the heavy weight of expectation and conflicting pressures from many directions. Where this drive to succeed leads to irresponsible behaviour, this may force the hand of government to legislate. As their freedom to operate is restricted, business lea...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- List of Boxes

- List of Abbreviations

- Foreword

- Preface

- Introduction

- PART I A Changing World

- PART II Strategic Appraisal

- PART III Strategic Options

- PART IV Delivering the Strategy

- Conclusion

- References

- Index