![]()

1

Yann Dedet

It was when talking to Yann (and Martine Barraqué) in researching a book on Truffaut’s La Nuit Americaine (Day for Night) that the idea of a book on European film editors first occurred to me. So it is appropriate to begin this new edition with our original conversation.

Yann’s first films as an editor were with François Truffaut. He subsequently became the editor for amongst others, Maurice Pialat. He had recently directed his first feature length film, Le Pays du Chien qui Chante (The Land of the Singing Dog, 2002).

YD: I was born in Paris in 1946. My father was a publisher, including for instance the last three books by Antonin Artaud.

My mother was an “antiquaire” (antique dealer). I was very “moyen” (average) at school, but I developed an early interest in the theatre (Shakespeare, Strindberg).

My father took me to see my first film when I was eight. It was L’Homme des Vallées Perdues (Shane, 1953) by George Stevens. I ran out of the theatre, crying, when the dog howled to death at his master’s funeral. Later Peter Pan, Snow White, many peplums (sword and sandal) and westerns and then the first Chaplin films that I saw (Les temps modernes (Modern Times, 1936), and The Great Dictator, 1942) made a bridge to reality by such a mixture of joy and sadness. From where, I think, I got the idea of making films myself; a hope materialised by my grandfather when I was eleven, by the gift of a Paillard-Bolex eight millimetres and the making of “movies”. Other early films that made an impression on me were La Prison (The Devil’s Wanton, 1949) by Ingmar Bergman, Fellini’s Eight-and-a-half (1963) and Visconti’s Il Gattopardo (The Leopard, 1963).

Culturally, my first loves in music were Vivaldi, Moussorgsky, Prokofiev, Tchaikovsky, Varese, and Léo Ferré; in literature Julien Green, Henri Bosco, André D’hotel, and Ionesco.

My first passion was really theatre, maybe more serious because nearer to literature. The shock was the sight, in an editing room of the two “celluloids,” the brown sound and the grey (black and white) image, falling together in a box under the Moritone, (editing machine) mixed together like two snakes, and the nazillard, direct sound making its way above the strong noise of the motor and the celluloid splices passing “en claquant” (clacking) through the wheels of this magical and physical machine.

But at the time the pleasure of holding my little camera and the fact of choosing what was to be filmed was stronger than the idea of editing, less instinctive for the moment than framing. So I want to go to the Vaugirard School of Photography to learn framing. But studies went worse and worse because of the awakening of adolescent “pulsions” (urges) which pushed me to make with my Paillard-Bolex a very destructive and auto-destructive little movie in the mood of Erostrate by Sartre.

So no Vaugirard and instead one month in London to improve my English (and for my parents to put me far away from a very “pousse-au-crime” (crime-pushing) friend I admired very much) and six months in a film laboratory where I spent half my time synchronising dailies; another shock coming from my 8mm to this huge 35mm and even more when one day I touched 70mm from Playtime of Tati.

But I only really knew what editing was when I edited myself the sequences that were reshot for the—very bad—movie I made my first stage (trainee-ship) on. Happily there were a lot of bad sequences reshot and, coming in at around six in the morning, I tried all sorts of stupid cuts, and even splicing the film upside down, drawing on the film, etc. At the time it was only a game and now it is real work but happily the pleasure of playing is still there. As Pialat says, “It’s only when you have fun that you work well.”

The editor I saw working on my first stage (attachment) was so bad that I could begin by learning, what not to do, a very important step. Afterwards, Claudine Bouché, whom I assisted on La Mariée Était en Noir (The Bride Wore Black, 1967) confirmed in me that playing in work is essential, and Truffaut was so incredibly easily changing the meaning of the material, of the shots, twisting, reversing them and placing them so freely out of their first place that once again I felt the “ludique” (play) side of editing.

Then Agnès Guillemot, edited the next four Truffaut movies, and he asked her to keep me as assistant. Agnès has two enormous qualities; firstly, she tries nearly every solution, even the ones which look logically bad, and secondly, she lets the movie breathe, almost by itself, waiting very often for the solutions to become obvious.

She puts shots, not cuts, next to each other to try to see what is the effect between the two shots, but not the splice, the interior of each shot, what it says, the meaning, the colour, the pace of the shot. Then she cuts entire shots out and suddenly there is something obvious between the shots that remain and then she makes the “raccord” (match) between the shots but not before. It’s like you don’t take the skin off the chicken until you know it is a good piece. So Agnès has a good way of attacking the work, which is waiting—looking—thinking—hearing the music then “tout à coup” (suddenly) this piece can be out because it’s not the mood of the whole thing. It’s very delicate work.

For me it is different. I replaced this method by being very “pressé,” always a guy in a hurry. So very quickly I focus on a centre—the shot from the rushes which speaks to me—and little by little I extend, maybe too fast but sometimes it has good results because it provokes interest in the rest of the rushes.

François (Truffaut) hated the cut on action, like the Americans always do. A gesture should be complete and not interrupted by a cut and/or change of angle. Rather the rhythm should dictate the moment. Also I don’t like “champ-contre-champ” (matching two-shots), with a piece of somebody on the edge of frame. It’s like a stupid proof, just for what? It wastes the energy of the image; putting technique before art.

I don’t remember this kind of thing in silent cinema. I think it is the demand of sound, suppressing the character of ancient cinema.

*************

I had an entirely different experience with Dušan Makevejev on Sweet Movie (1974). The structure there is not essentially narrative but essentially emotive; that a scene follows another by opposition or by similitude is the important thing. At the wall of the editing room on the list of the sequences, each sequence is characterised by a little coded sign which means: “something violent,” “something sweet,” “something sexual,” “something animal,” “something horrifying,” “something tender,” “something historical,” “something childish,” etc. The way he chooses the pieces to edit is very special too; totally un-narrative at first, just putting cut—cut the pieces he likes without any apparent idea of construction.

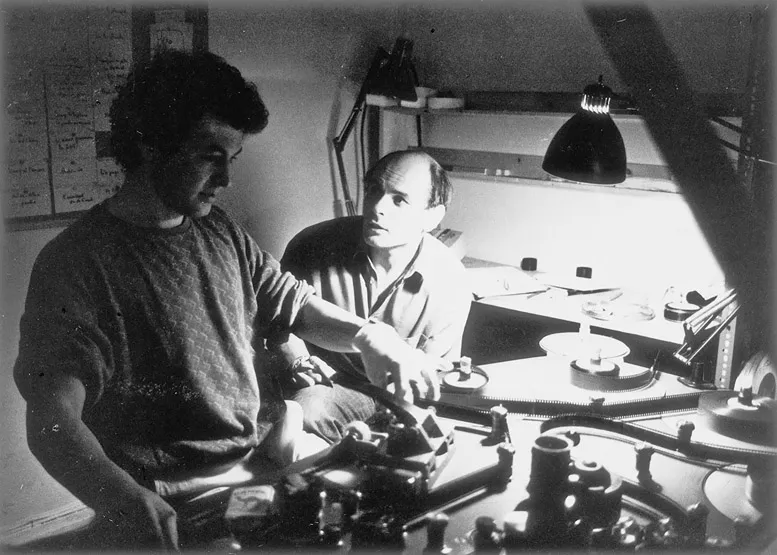

Yann Dedet (on left) cutting with Jean-François Stévenin

But the greatest editor for me is the director Jean-François Stévenin, always chasing the “défauts” (flaws) in each shot. I like imperfection; things should be seen and heard that are défaut. Films need arrhythmic things, too long or too short. Stévenin’s movies are full of ellipses. He has a certain pleasure, and talent too, for breaking the logic of a scene, and mixing the ups and downs of an actor in so complete a disorder that he amplifies the trouble—that the actor was trying to express—ten times more than expected.

Then I worked with Patrick Grandperret (Mona et Moi, 1989) who is in some way the opposite of Stévenin, framing himself, shooting his movies in a total disorder, rewriting the script every night, and changing direction the next day. In all this mess editing is the moment when he really writes, cutting one shot to another so that the movie looks like one long sweet movement (Stévenin on the contrary shoots very controlled plan-sequences and editing is the moment of putting everything in “living disorder”).

With these four directors, Truffaut, Makavejev, Stévenin, and Grandperret, I must say that this period was my school time, I was learning and learning.

RC: How about other directors you have worked with?

YD: Maurice Pialat was the second director to choose me “against” Truffaut (the first was Makavejev) having respect but no approbation for Truffaut’s style. In fact, as often as not, opposition was the game, the idea being to compare and oppose one idea of cinema to another, for the purpose of refining his style. Or by using methods from other styles, or not using them, by discovering something which improves and goes further in his own style. Very drastic, very radical solutions are found this way, often by leaving the problem without solution.

After that I worked with Philippe Garell: with him each time you cut five frames, you check the entire twenty-minute reel to feel whether the inside music of the film has been broken or not. Then with Cédric Kahn, who is an incredible mix of instinct and reflection; with Manuel Poirier whose dream would be (as for Pialat in fact) not to cut; the less shots there are, the better it is to let time flow.

With Claire Denis we spoke a lot, but it is as if words couldn’t be of any use. Only listening to the film counts. The important thing about Claire is that she never wants to say what she wants; she is suspicious of words. So our dialogue is always going around the subject. Like Stévenin, they both don’t want the words to come before the act of building the film.

It is the opposite with Pialat; the talk is nourishing the film; a way of liking life. He believes you will never have a good movie if you don’t have fun with it. He is suffering because you have to cut, so is trying to cut by playing with cutting. It is a magical moment when the “réalisateur danse devant son film” (the director dances in front of his film).

My key experiences as an editor have been Truffaut for learning (he was my cinema father—I never read Bazin who was the grandfather), Stévenin for the feeling that everything can be tried, even what seems impossible, and Pialat who seems totally untechnical, who is as free as life.

For example, in Van Gogh (1991), in the cabaret sequence, I remember a savage cut in the music, surely unbearable to a musician, a savage cut which, “en rapport avec” (in connection with) the other cuts and jumps of image and sound in this sequence, was something which gave “équilibre” (balance) to the whole thing, as if life lay in the erratic cuts more than in the logical cuts. For me this kind of thing is impossible to replace by another “figure de style” (stylistic device).

RC: Can you talk about the difference between European and American Cinema?

YD: What seems to be apparent in most of American Cinema is a very important rational thinking at work: everything has to make sense, and to be precise, like subtitled, the sound saying the same thing as the image, and shots explaining and saying again and again the same idea, which is already over-expressed by the intentional faceplaying of the actors, the endless repetitions of the dialogues. The American ideal of cinema is an infinite continuity of “pléonasmes” (emphasising the obvious).

In European cinema you can sometimes see “un plan pour rien” (a shot for nothing) different, elsewhere, out of the movie, but which is in fact the movie. Sometimes when I’m very glad for a movie I say, “un film pour rien” it was just like a part of life, or a good dream. There is no story, no thesis to defend, there is no purpose, just doing music, letting time flow. Show it how it flows, marvelously. This is un film pour rien.

In the storytelling process European editors have to work like musicians, like rowers in rapids, trying to listen to the sound of the falls, not to be pulled towards them by the flow.

Maybe the biggest utility of an editor is to be like a mirror, but one who gives back another image to the director. Often, just listening to what someone says makes the “sayer” aware of the fact that he just said something wrong or incomplete or stupid or … and this is part of the role of an editor and this quality—just being there to receive, even saying nothing—helps the one who creates to “see” as he never saw his work.

For the editor, arriving first at work is very important, to take possession of the film as much as working alone on it sometimes. The editor is coming late to the film: he didn’t dream, didn’t write, didn’t direct the film and he has to take the film, to touch it, break it and splice it to understand how the film is thought and how it reacts.

The ideal editor is a humble director.

The difficulty in everything is not to be perfect. An editor must be half-intelligent—half-instinctive, half-romantic—half-logical, half-imaginative—half-“terre à terre” (down to earth), half-here—half-dreaming…. This makes a lot of halves and I would say that such a mess is more a gift of nature than something that can be worked and built.

The first reason for choosing to work on a movie is the director, and most of all how he speaks about cinema—or about life. All those who are very aware about techniques or about the business world of cinema are very repulsive to me. The best is, as Pialat does, to speak music, sex, painting, mountains, sculpture, love … (Although the most revealing thing for me was when he asked me ten years before we worked together: “Do you like films in which the guy says ‘let’s go to the sea,’ and the next scene is on the seashore?”)

Very seldom scripts are good enough to really imagine how the movie will be, what I mean by good is poetic without being literary, giving the “envie” (desire) to see images and hear sounds of a special universe, like “not really belonging to this planet” as John Boorman said about Passe Montagne (Stévenin, 1978).

RC: Do you read the script before editing a film?

YD: The best thing is not to read a script and to judge a film only by seeing the images and listening to the sounds, in order to edit, not with the ideas but with the filmed material.

Sometimes when I am asked for I read the script very fast never reading over to try to have the screening-feeling; incomprehensible things staying incomprehensible.

RC: Do you have preferences about the technology and the space for editing?

YD: My best editing machine was the Moritone, something like a Moviola but a little bigger, on which I edited standing up, thus improving the physical pleasure of editing. Flat-bed machines give less pleasure.

What is very difficult in actual editing rooms—not conceived by editors—is the totally stupid place of windows (even on the ceiling! I often have to bring curtains from home) and the horrible noise of air-conditioning (as in movie theatres nowadays it is quite impossible to listen to “tenu” (weak) sound or to really see a night scene because of the exit or toilet lights).

I always need a big board on which I can change the place of the sequences, written in several different coded colours, depending on the kind of narration: a colour by character, place or period or any essential point of view regarding the nature of the particular movie. And like a real cowboy, I can’t have a door at my back in the editing room.

I try to be very near to what I think the film must be when I am editing, as if the mix would be the day after, except for very enormous errors: much too long or too short shots, bad takes, holes in the narration (storytelling), objectionable repetitions, which I think are necessary to the deep thinking about the film. Sometimes the question asked by the film is so huge that you have (I have) to make the proof by the contrary, and it can happen that one or several of these mistakes leads to an idea which fits the film. Or that this attempt to be like the opposite of the film, it leads to express by opposition that the direction of the rest of the film is confirmed by...