![]()

Section II

The autonomous inside

The autonomy of the interior offers the possibility for alternate aesthetic or sensory experiences that challenge the way we inhabit the world. Free from uncontrolled variations in climate and context, inhabitable art pieces, stage sets, merchandising displays, and infrastructural conditions allow us to inhabit at times fantastical realities. They offer new spatial experiences that challenge the confines of traditional programmatic elements, typical code requirements or other pragmatic limitations. These interiors have the unique ability to delight and surprise us, changing environmental expectations through this distinct condition of contextual independence.

Provocations:

- Can autonomous interiors narrate their own context?

- Can sequenced interiors operate as a networked infrastructural system independent of its enclosed context?

- How does inhabitable space dictate personal and social behavior? How do personal and social behaviors dictate inhabitable space?

![]()

04 Artists occupying interiors occupying artists

Alex Schweder

No matter his or her medium, every artist creates an interior, a subjective experience inside the minds of the audience. Within the context of this publication, suggesting that the expertise of producing interior space is also in the purview of a discipline other than interior design may read as an affront to some. This provocation, however, is meant to enrich the field of interior design, not dilute it. Through the artworks featured in this chapter, three of which I co-created, I will argue that the interior qualities of designed environments are so imbricated with the interior subjectivities of their occupants that it is not possible to discuss the interior of a building without also addressing the psychological interiors of the inhabitants. Interiors are made from both subjectivity and sofas, and designers not only have legitimacy in working with both but they can be as playful with behavior as they have become with bricks.

In studying spaces that artists design and occupy, this chapter will show that not only are interiors expressions of their inhabitants’ identities, struggles, and relationships, but they produce them as well. To map the relationship between interior space and inhabitant as suggested, it is useful to see how artists forged a similar path in their field. By tracing how the subjectivity of artistic audiences came to be constituted as the art itself, I will argue that the same relationship that exists between performance art and audience also exists between inhabited space and inhabitant.

Historically, visitors to museums were thought to passively receive meaning emanating from a painting or sculpture1 (Hill, 2003: 22), thus locating the value of the work in the material object itself rather than its impact on viewers. Frustrated by the reduction of their work to a commodity, artists working in the mid-twentieth century began shifting the definition of art away from marketable objects toward ineffable subjective experiences. As a strategy toward this end, artists recast viewers of their works from passive consumers into collaborative producers whose perception of an artwork produced the meaning. As part of this change, artists began making immersive environments that stimulated the full sensorium of their visitors’ bodies.

Artists who make interiors today heighten the perception of their audiences by breaking their habituated ways of using spaces, often riffing on the everyday environments that interior designers produce. These artists identify their trope as “installation art.” While their palettes overlap with interior design through the use of materials, scale, and the reconfiguration of existing spaces, a key difference between installation art and interior design is how each discipline thinks about occupants. Where interior designers might ask: “How does this environment reflect who my client is?”, an installation artist might ask: “Who will a person become when entering the space I make?” One question characterizes a subject’s psychological interior as static, while the latter understands subjectivity as plastic. It is because of their allowance for fluidity in subjectivity that I choose to reference artistic endeavors rather than engage the history of design, which contains prevalent and problematic attitudes towards behavior evidenced in movements such as functionalism.

To explore the idea that corporeal occupation of an interior space can beget psychological transformation, performance artists have lived for several days or even weeks in environments they built. From the late twentieth century, Chris Burden’s Five Day Locker Piece (1971)2, Vito Acconci’s Seed Bed (1971)3, or Linda Montano and Tehching Hsieh’s Cage Piece (1978–79)4 are a few such historical precedents. Artists today build on such works by constructing and occupying extreme interiors and using them as giant microscopes through which they can more clearly see how these environments influence their subjectivities.

Sometimes, however, an artist’s planned outcome and what actually happens during a performance do not align. Marcel Duchamp spoke of this in 1957 as the “art coefficient” (Lebel, 1959: 77–78), referring to this gap between artistic intention and its reception. Here, Duchamp claims, is where creativity and art occur, in the space where clear communication between people breaks down and interpretation is used to construct a makeshift bridge over the chasm of possible meanings. In the performance artworks that I will be discussing, the authors occupy their works with the intention of the space precipitating a psychic transformation. The only people who can verify if the intended change in subjectivity occurs, however, are the artists themselves. This puts them in the awkward position of acknowledging that a work did not actualize their pre-inhabitation hopes if something unexpected occurred. Duchamp’s theory is perhaps most helpful in this moment, when the person that the artist wanted to become and what they actually became are not the same thing. Duchamp’s position gives artists a way around the idea that living in their work is a failure if the result is different from the point of departure intention. Duchamp’s theory affirms that the most creative moments are produced by the unknown and unexpected.

To explore the connection between subjective alteration and spatial inhabitation I will discuss six artworks in this chapter: three from the practices of other artists and three from my own. While I can only corroborate what I experienced, discussing the three initial works will provide a context for the latter, which have similar practices and ambitions.

The House with the Ocean View

In 2002 Marina Abramovic´, whose seminal performance art spans decades, lived in The House with the Ocean View between November 15 and 26 at Sean Kelly, a gallery in New York City. Her artistic intent was to endure the stresses of a 12-day occupation of an interior comprised of only three sparsely furnished rooms suspended above the gallery floor; one for sleeping, one for sitting and one for ablution. She only consumed water, never spoke to the audience, and performed every action—including bathing and urinating—in front of her audience. Abramovic´ describes the set up as ritualized fasting using the repetition of both everyday actions and a metronome to induce a trance-like state wherein she is “purified.” While purification is a slippery term in this context (Birringer, 2003),5 it does suggest the artist’s desire to influence her subjectivity through occupation of an interior space. By continuously living in this ascetic interior, I interpret that she wished to become as empty as her environment.

What Abramovic´ filled herself up with are the silent connections she has with her audience. As the title of the work suggests, the artist considered her audience from the very start; the mass of their presence was the “ocean.” Throughout the work she singled out members of her audience (as she would come to do again a decade later in her performance of The Artist is Present), and in silence they would “exchange energy,” as the artist described it. According to the artist, a connection between them was made that could not have come about if they were in a more distracted state. For Abramovic´, empathy and connection are facilitated by space and circumstance; so in an adjacent room there was a bed and costume that a member of the audience could occupy for one hour to become more like the artist. From this set up I speculate that Abramovic´’s intention for her and her audience’s subjectivity was to transform mental experience into something shared, and that her vehicle to do so was the interior occupied by both.

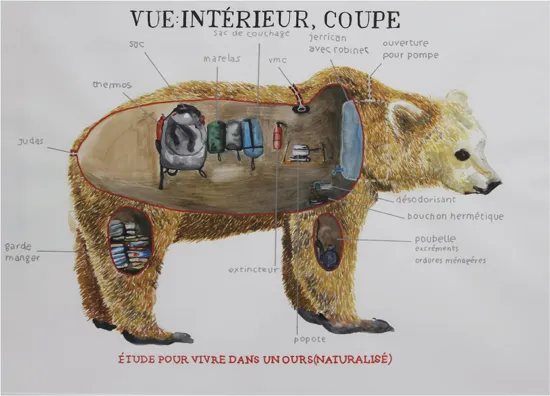

Dans la peau de l’ours

French artist Abraham Poincheval also used physical deprivation to induce mental alteration in his 2014 occupation performance Dans la peau de l’ours (In the bear’s skin). Poincheval, in his own words,6 wanted to become more “bear like.” To induce the hibernation associated with this animal, Poincheval lived in the interior of a bear sculpture that he fabricated using a wooden formwork. Without leaving this womb-like space for 13 days, he slept, read, and lived his life in what looked like a taxidermy bear on the outside and a Tom Sachs7 spaceship on the inside. Before beginning the performance Poincheval had loaded up one leg with the food he thought a bear might eat (honey, berries, and the like), designed a second leg to supply water and collect urine, a third leg collected trash, and the final leg let in fresh air. Almost as a photo-negative of Abramovic´’s relationship with her audience, Poincheval’s audience could not see him but were encouraged to chat with him to keep him company. Even though the somatic artist/audience exchanges were different, both relied on the interior spaces8 of exhibition and inhabitation to precipitate psychic change.

Figure 4.1

Étude pour vivre dans un ours (naturalisé) vue extérieure. Abraham Poincheval. © Collection Musée Gassendi, Digne-les-Bains

Figure 4.2

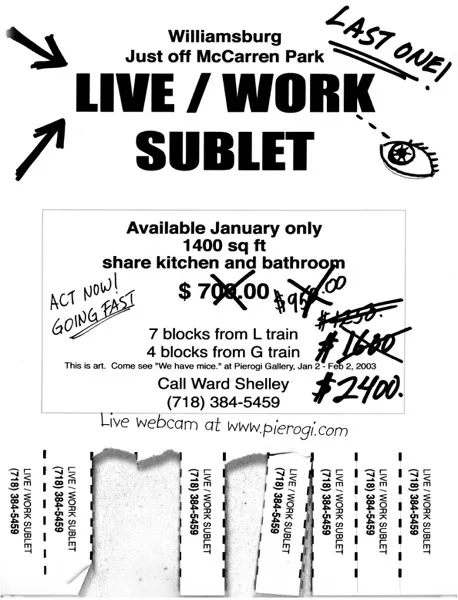

We Have Mice, Ward Shelley, 2004

We Have Mice

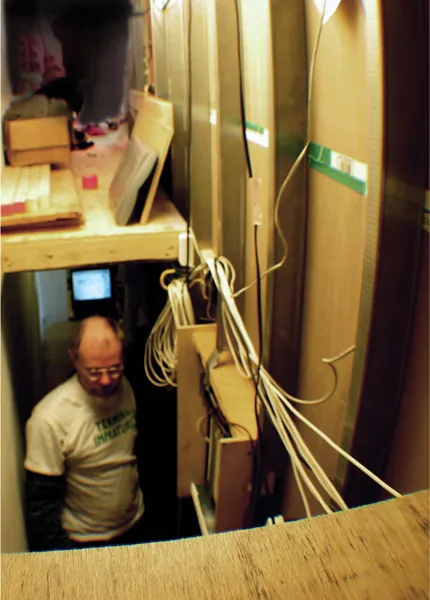

“Becoming animal” was also the point of departure for a third interior inhabitation, by artist Ward Shelley in 2004 when he lived mouse-like in the walls of Pierogi Gallery (then located in New York’s emergently trendy Williamsburg neighborhood). His occupation of the gallery’s poché was a metaphor for the plight of artists in the neighborhood, and only unexpectedly did his occupation induce a shift in subjectivity. Mice in the company of humans, for Shelley, are the less powerful creatures and are thus forced to occupy the periphery of a space, just as the artists who moved into the neighborhood in the 1990s were being forced to do because of gentrification. Initially intended to be a one-month performance and occupation, Shelley left only to “forage for food, materials and mating opportunities.” (Cotter, 2004). Shelley’s interactions were quite different from those of either Abramovic´ or Poincheval. As it would be for a mouse, evidence of his occupation would emerge obliquely through “droppings.” In Shelley’s case these were notecards featuring artwork that he made while living within the gallery walls and slid through slits cut in the gypsum board. These pieces of paper were inscribed with sayings such as “Self-critique just isn’t sexy, I don’t know why,” or “I’m judging you too.”

Figure 4.3

We Have Mice, Ward Shelley, 2004

Figure 4.4

We Have Mice, Ward Shelley, 2004

We Have Mice was written up in several high-profile publications, including The New York Times. Accolades like these padded the artist’s psychological interior against the stress normally experienced when inhabiting an extreme physical interior, until the exhibition was extended for a week. He recounted9 how he experienced a psychic break after the performance unexpectedly went beyond its anticipated duration. This change felt like a loss of autonomy, and Shelley reported that his burrow began to feel like a detention cell. Caged animal-like b...