eBook - ePub

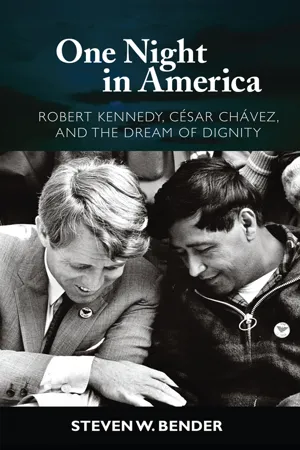

One Night in America

Robert Kennedy, Cesar Chavez, and the Dream of Dignity

- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"Courageous." -Ilan Stavans, author of Spanglish: The Making of a New American Language Robert Kennedy and Cesar Chavez came from opposite sides of the tracks of race and class that still divide Americans. Both optimists, Kennedy and Chavez shared a common vision of equality. They united in the 1960s to crusade for the rights of migrant farm workers. Farm workers faded from public consciousness following Kennedy's assassination and Chavez's early passing. Yet the work of Kennedy and Chavez continues to reverberate in America today. Bender chronicles their warm friendship and embraces their bold political vision for making the American dream a reality for all. Although many books discuss Kennedy or Chavez individually, this is the first book to capture their multifaceted relationship and its relevance to mainstream U.S. politics and Latino/a politics today. Bender examines their shared legacy and its continuing influence on political issues including immigration, education, war, poverty, and religion. Mapping a new political path for Mexican Americans and the poor of all backgrounds, this book argues that there is still time to prove Kennedy and Chavez right.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access One Night in America by Steven W. Bender in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

A Friendship Cut Short

CHAPTER ONE

Viva (John) Kennedy

I think that [Robert Kennedy and César Chávez] were kindred spirits before they met. They both recognized in the other the same values and the same hope for the country and hope for the [underprivileged].—Ethel Kennedy1

Robert Kennedy and César Chávez first met in East Los Angeles in 1959.2 There is nothing to indicate that their initial meeting was remarkable or that it sparked their inspiring friendship. That happened later, in 1966, when Kennedy went to central California as a U.S. senator from New York to participate in Senate subcommittee hearings on farm labor. But their 1959 meeting was significant as it embodied their early but skillful efforts in the political arena, which set the stage for Chávez to campaign for Kennedy in the 1968 election. Chávez would return to Los Angeles in 1968 as a rural farm labor organizer, but his urban political organizing background among Mexican Americans in the barrio would boost Robert Kennedy to victory in California’s primary that year, on an election night that represents both triumph and tragedy for the Mexican American experience.

Born in rural Arizona in 1927, Chávez went to California as a child and worked the fields picking fruits, vegetables, and cotton. So that he could help provide for his family, he quit school after the eighth grade. After serving in the Navy at seventeen in the final year of World War II, Chávez married and headed to northern California to work for a lumber company in the coastal redwoods. Not long after, Chávez and his wife Helen moved to the city—to the barrio known as Sal Si Puedes ( translated, “get out if you can”) in the California city of San Jose. While employed at a lumber mill there, Chávez was recruited to work on behalf of the Community Service Organization (CSO).

Formed in 1947 in East Los Angeles, the CSO was spurred in part by the defeat that year of Mexican American Edward Roybal in his campaign for the Los Angeles city council. Roybal’s supporters started the CSO with the aid of Fred Ross, an organizer for the Chicago-based group Industrial Area Foundation, which sought to politically mobilize poor neighborhoods.3 In addition to holding forums to discuss community problems and winning such community improvements as paved streets, sidewalks, traffic signals, recreational facilities, and clinics,4 the CSO had a political bent through Ross, swiftly registering 40,000 new voters in East Los Angeles.5 In the 1949 election, these newly minted Mexican American voters contributed to Roybal’s election as the first Mexican American on the Los Angeles city council since 1881;6 Roybal later became the first Mexican American representative elected to Congress from California. It was the CSO that took Ross to the Sal Si Puedes barrio in 1952 during his effort to establish a San Jose chapter. Chávez was helping a local priest address the problems of Mexican farm workers, and the priest pointed Ross to Chávez. The night of their first meeting, Chávez began work registering Mexican American voters in San Jose, laboring by day at the lumberyard and by night going door to door. Soon, Chávez was chairing the registration campaign in San Jose for CSO.

Most of these newly registered voters would vote Democrat. Scholars attribute this Democratic allegiance of Mexican American voters at the time to the New Deal administration of Franklin Delano Roosevelt in the 1930s and early 1940s, some of whose programs benefited them. Their loyalty was cemented by the thousands of Mexican Americans, like Chávez, who served in World War II under a Democratic president.7 Perhaps fearing the impact of these new Mexican American registrants in San Jose, Republican operatives stalked the voting booths in the 1952 election, demanding that Mexican American voters confirm their citizenship.8 With Chávez taking a leadership role, the CSO fled a complaint against the Republican Central Committee with federal authorities, who instructed the Republicans not to interfere with CSO’s organizing.

To increase the eligible electorate, Chávez began helping Mexican immigrants obtain citizenship. César’s involvement with the CSO led him to Oakland, where he organized a CSO chapter; to the San Joaquin Valley; and to Oxnard on the California coast. By 1959, Chávez moved his family to East Los Angeles, when he was asked to come to Los Angeles to work at the CSO headquarters, located between downtown and East Los Angeles, and promoted to serve as CSO’s national director.

At that time, 80 percent of the Mexican American population in the United States lived in urban areas such as Los Angeles, San Antonio, and Chicago.9 Los Angeles County housed the largest Mexican population in the United States, starting the 1960s with 576,716 people and ending the decade with 1,228,593 Mexican residents. At the same time, the Anglo population in Los Angeles County actually decreased.10 Anglos in Los Angeles fed the inner city for the suburbs, commuting to work on freeways that decimated neighborhoods throughout the increasingly Mexican communities east of down town Los Angeles. Once home to substantial numbers of Anglos and Jewish Americans, the East Los Angeles area browned in the 1950s and 1960s as it became more Mexican, and more poor. Compounding the poverty of the barrio was the absence of political power of the Mexican American community in Los Angeles.11 In addition to the challenges of galvanizing young, poor, immigrant voters, gerrymandered legislative districts fractured the barrio. Ensuring local, state, and federal underrepresentation, the California legislature in the early 1960s split East Los Angeles and the surrounding areas into nine assembly districts, seven Senate districts, and six congressional districts, so that no one district had more than 30 percent of its registered voters of Mexican American heritage.12 From 1962 to 1985, no Mexican American or other Latino was elected to the city council or other citywide office in Los Angeles.13

Managing his brother John’s 1960 presidential campaign, Robert Kennedy came to Los Angeles in late November or early December 1959 and met at two in the morning with César Chávez in César’s capacity as director of the CSO. They discussed the CSO’s voter registration drive among Mexican Americans. Kennedy’s campaign staff pitched to Chávez a public relations approach to registering voters that relied on radio and newspaper publicity. But Chávez disagreed and contended the only way to register voters in the area was by going door to door: “So I was outlining a campaign where we would go to every Spanish-speaking door in the state, minimizing the radio and newspaper and all that, saying that that wasn’t going to get them to vote, to register.”14 Robert Kennedy arrived late at the early-morning meeting and listened to Chávez explain his strategy to the campaign team. After listening, Kennedy intervened on Chávez’s behalf and instructed his team, “Let him do it the way he’s used to doing it. It’s been effective.”15

The 1960 national Democratic Party convention, held in Los Angeles, nominated Senator John F. Kennedy. California’s Edward Roybal and two other Mexican American politicians from New Mexico and Texas wanted to enhance the involvement of Mexican Americans in the Kennedy campaign, and after the convention they spoke to campaign manager Robert Kennedy.16 He approved their idea of outreach to the Mexican American community. Overseen by a Latino17 law student from George Washington University, the outreach effort took the name Viva Kennedy. The Viva slogan actually came from the Nixon camp, which had rejected the idea of galvanizing the Latino population through an organizing “Viva” campaign.18 Adopting the symbol of Senator John Kennedy’s riding a burro while wearing an oversized sombrero emblazoned with the words Viva Kennedy, the Viva Kennedy effort launched by forming local clubs that answered to Robert Kennedy rather than to the state Democratic Party leadership.19

The Viva Kennedy clubs sought to connect John Kennedy to the Mexican American community through Kennedy’s progressive politics, which were sympathetic to the poor. Other selling points included Kennedy’s ethnic Irish heritage—Mexican American voters, plagued by racism such as signs in the Southwest reading “No Mexicans or Dogs Allowed,”20 could appreciate the struggles of the Irish, who faced their own discriminatory signs on the East Coast, such as “No Irish Need Apply.”21 Further, Kennedy was a Catholic, as was an overwhelming percentage of the Mexican American population, and his wife spoke Spanish. As a biographer of the Viva Kennedy club campaign effort described:

For Club leaders, [John] Kennedy’s religious affiliation represented a cultural bridge to the Mexican American community. His Catholicism meant that he understood religious and cultural prejudices. It meant he understood the [funding] dilemma of Catholic schools…. And it meant that he valued family and tradition. The fact that his wife Jacqueline understood and spoke Spanish meant that Kennedy could communicate with Mexican Americans and understand their needs. With these points to sell, Mexican American reformers felt confident that they could get barrio residents to vote for him. The fact that he was simpatico [a nice guy] made it an easier sell.22

Organizers initiated Viva Kennedy clubs throughout the United States in about thirty states,23 and reached out beyond Mexican Americans to Puerto Ricans, Cubans, and those from Central and South America. In California, the Viva Kennedy effort tapped into the existing organization of the Mexican American Political Association, formed in Fresno in spring 1959 and chaired by Edward Roybal. Roybal served as the liaison between the California clubs and the national Kennedy headquarters. Central to the Viva Kennedy effort was registering new Mexican American and other Latino voters, and the Chávez-led CSO helped to conduct this mission. By the time of the election, an estimated 140,000 Mexican Americans were newly registered to vote in California.24 César Chávez saw the Viva Kennedy campaign primarily as a public relations tool, distinct from the hands-on organizers of the CSO, who were doing the real work of registering voters. As Chávez explained, the CSO was “cleared” of any accountability to the Viva Kennedy club infrastructure: “We don’t want any of those guys telling us what to do. We do it ourselves. We’re judged on whether we did fail or we didn’t, but we don’t want any committee or anything in between us.”25 Later, when Time magazine attributed the success of the drive to register Spanish-speaking voters to the Viva Kennedy organization, Chávez asked CSO organizer Dolores Huerta to protest this to Robert Kennedy. As Huerta recalls, she confronted Kennedy with the Time magazine in her hand, and Kennedy threw up his hands, saying “I know, I know.”26 Kennedy agreed that the story was a mistake and a few weeks later Time published a letter from Kennedy revealing “[t]he credit for this outstanding job of registration should go to the Community Service Organization, which for a number of years has been dedicated to this work among Spanish-speaking citizens of California.”27

John Kennedy came to East Los Angeles in early November during his 1960 presidential campaign, speaking after dark at the East Los Angeles Junior College stadium, which s...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Acknowledgments

- Part I A Friendship Cut Short

- Part II The Dream of Dignity Survives

- Part III Lessons from 1968: Latino Politics Today

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Index

- About the Author