- 222 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Economic Integration and Development in Africa

About this book

The debates over what African economic integration and development actually entails continue across international economic organizations, national governments and NGOs. Despite the glare of media attention and the position this issue has on international political agendas, few comprehensive accounts exist that fully examine why this process will be inevitable in the 21st century and how integration of national economies can be attuned to attaining the socio-economic goals and aspirations of member-countries. This book addresses this problem. It combines theory with application, enumerating the imperatives and initiatives governments will be forced to confront; providing insights for educators and students in African development, for policy makers in African governments, and for inter-governmental organizations.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Economic Integration and Development in Africa by Henry Kyambalesa,Mathurin C. Houngnikpo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Conceptual Underpinnings

This introductory chapter is devoted to a brief survey of important concepts upon which the integration of national economies worldwide is predicated. Specifically, the following themes are discussed in the chapter: the various forms of economic integration, the potential effects associated with the integration of national economies, pre-conditions for viable and beneficial integration of national economies, and the ‘theory of the second best.’

1.1 Forms of Integration

Essentially, the term ‘economic integration’ is used in this book to refer to the formation of an inter-governmental organization (IGO) by three or more countries to create a larger and more open economy expected to benefit member-countries. Theoretically, the process of economic integration may take any of the following forms, each of which may represent a different stage of integration if member-countries have a desire to pursue the integration of their national economies to its logical conclusion:

(a) preferential trade arrangements, which represent the form of loose economic integration whereby participating countries scale down barriers to the movement of goods in their trade with each other;

(b) a free trade area, which basically entails the complete removal of trade barriers among member-countries, while each member-country maintains separate trade policies with nonmembers;

(c) a customs union, whereby member-countries venture beyond the removal of trade barriers among them and adopt a common external trade policy with all nonmembers;

(d) a common market, whose nature involves the removal of all barriers to the movement of factors of production (particularly labor and capital) among member-countries in addition to the requirements of a customs union cited above;

(e) an economic union, which essentially requires member-countries to go beyond the requirements of a common market by unifying the economic institutions of the member-countries, and the coordination of their economic policies;

(f) a monetary union, whereby the member-countries, in addition to satisfying the requirements of an economic union, adopt a common currency, as well as create and use a common, supranational central bank; and

(g) a political union, whereby cooperating countries in a monetary union eventually create a regional bloc that is akin to a nation-state or federal government by creating centralized political institutions, including a regional parliament.1

The first four stages or forms of integration represent what Gerber has referred to as ‘shallow integration,’ while the last three represent what he has designated as ‘deep integration.’2 Essentially, the term ‘shallow integration’ refers to any form or stage of economic integration whose scope is limited to border-related issues—that is, tariffs and non-tariff trade barriers (NTBs).

‘Deep integration,’ on the other hand, goes beyond border-related issues; among other things, it entails harmonization of member-countries’ important economic institutions, as well as legal, product-safety, labeling, environmental, and technical standards.

1.2 Effects of Integration

There are generally four potential effects associated with economic integration; they are as follows: static effects, dynamic effects, trade deflection, and counterfeit labeling. A brief survey of these four effects constitutes the subject matter of the remainder of this section.3

The Static Effects4

Essentially, the ‘static effects’ that are associated with the process of economic integration emanate from shifts (induced by the integration of any three or more national economies) in the production of certain export products from one member-country to another member-country, or from a nonmember-country to one of the member-countries. More specifically, static effects can result either in a shift in product origin from a high-cost member-country producer to a low-cost member-country producer (trade creation) or in a shift in product origin from a low-cost nonmember-country producer to a high-cost member-country producer (trade diversion).

While the first form of static effects—that is, trade creation—can improve member-countries’ welfare (since such a shift would represent a movement in the direction of the free-trade allocation of a country’s resources), trade diversion—the second effect—can generally reduce member-countries’ welfare because it represents a movement away from the free-trade allocation of resources.5

Accordingly, economic integration, as Sunny, Babikanyisa, Forcheh, and Akinboade have espoused, can enhance the socio-economic welfare of people in an integrated region, ‘provided that trade creation exceeds trade diversion.’6 However, countries in an economically integrated region ‘must not expect benefits to begin to accrue almost overnight … [because welfare gains] from such experiments are long term in nature.’7

In addition to the positive welfare effects of trade creation, there are other beneficial static effects of economic integration; they include the following:

(a) administrative savings which member-countries may realize from doing away with some of the functions of the customs departments of their national governments;8

(b) greater bargaining power, which countries collectively gain by being constituents of a viable economic bloc; and

(c) an improvement in member-countries’ collective terms of trade (TOT), which may occur when member-countries’ demand for imports from nonmember-countries plummets in the case of trade-diverting integration due to a reduction in their aggregate welfare.9

Before we turn to a survey of what are commonly referred to as the ‘dynamic effects’ of economic integration, it is perhaps essential to provide theoretical illustrations of both trade creation and trade diversion. In this endeavor, let us assume that the Zambian government is considering the prospect of engaging in economic integration with either Malawi or the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Also, let us assume that each of the three countries produces mattresses, and that Zambia is a medium-cost producer of mattresses, while Malawi and DRC are low-cost and high-cost producers, respectively.

In the remainder of this sub-section, let us briefly consider the nature of trade that would obtain under trade-creating and trade-diverting economic integration.

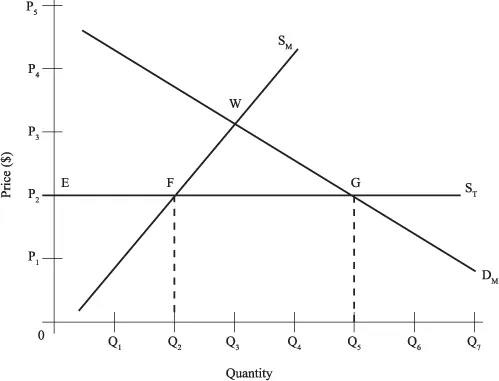

(a) Trade-creating integration: To reiterate, ‘trade creation’ occurs when there is a shift in product origin from a high-cost member-country producer to a low-cost member-country producer. Let us assume that Zambia—a medium-cost producer of mattresses—has decided to integrate its economy with that of Malawi—a low-cost producer of mattresses. Figure 1.1 portrays the nature of trade in mattresses that would obtain between the two countries prior to integration.

In Figure 1.1, DM and SM represent Zambia’s domestic demand and supply curves for mattresses, respectively, while curve ST represents Malawi’s perfectly elastic supply10 of mattresses to Zambia at a price of P2 per unit—a price which reflects a 100 per cent ad valorem tariff levied by the Zambian government on imported mattresses. The ‘W’ shown in the Figure represents the point at which mattresses—that is, Q3 units—are demanded and supplied within Zambia at a price of P3 per unit.

At the pre-integration price of P2 per unit, Zambians buy a total of EG (or Q5) mattresses; EF (or Q2) of the mattresses are produced locally in Zambia, while FG (or Q5 minus Q2) of them are imported from Malawi.

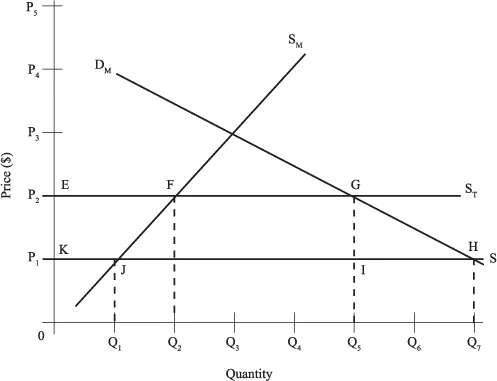

Figure 1.2 portrays the likely situation that would obtain if the Zambian and Malawian governments decided or agreed to integrate their countries’ economies. As before, DM and SM in the Figure represent Zambia’s domestic demand and supply curves, respectively, while curve ST represents Malawi’s perfectly elastic supply of mattresses to Zambia at the pre-integration and tariff-inclusive price of P2 per mattress.

Curve S represents Malawi’s perfectly elastic supply of mattresses to Zambia at the post-integration (or free-trade) price of P1 per unit—that is, the price of an imported mattress in Zambia after the removal of the 100 per cent ad valorem tariff initially imposed on imported mattresses.

We can interpret the nature of trade between the two countries after integration as follows: Zambia’s removal of the 100 per cent ad valorem tariff on imported mattresses results in a price reduction from P2 to P1 per unit, and leads to an increase in demand for mattresses by Zambians from EG (or Q5) to KH (or Q7) units; only KJ (or Q1) of the Q7 mattresses are produced locally in Zambia, and the remaining JH (or Q7 minus Q1) are imported from Malawi.

Figure 1.1 Before integration

Figure 1.2 After integration

By integrating its economy with that of Malawi, a low-cost producer of mattresses, Zambia has clearly increased its welfare by IH (or Q7 minus Q5) mattresses—that is, from EG (or Q5) to KH (or Q7) units. This increase represents what may be referred to as the ‘welfare effect’ associated with the integration of national economies.

Production of mattresses by Zambian manufacturers, however, declines from Q2 to Q1 units due to the availability of low-cost imports in the country. The decline represents what may be designated as the ‘production effect’ resulting from economic integration.

(b) Trade-diverting integration: As stated earlier, integration of national economies is said to be ‘trade-diverting’ if it leads to a shift in product origin from a low-cost nonmember-country producer to a high-cost member-country producer. To illustrate the effects of trade-diverting integration, let us assume that Zambia has decided to integrate its economy with that of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC)—a high-cost producer of mattresses—rather than with Malawi (a low-cost producer), and that the price of imported mattresses is now PC per unit.

This situation is depicted in Figure 1.3, where curve S1 represents DRC’s perfectly elastic supply of mattresses to Zambia at the post-integration price of PC per unit. The DM, SM, S, and ST which are shown in the Figure are defined in the preceding paragraphs.

We can interpret the nature of trade between Zambia and the DRC as follows: at the price of PC per unit, t...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Glossary

- The Authors

- The Contributors

- Preface

- 1 Conceptual Underpinnings

- 2 Necessity of Integration

- 3 Challenges and Imperatives

- 4 Regional Economic Groupings

- 5 Integration of Capital Markets in Eastern and Southern Africa

- 6 Exporting their Way out of Poverty: Twenty-first Century Challenges for Sub-Saharan Africa

- 7 A Recapitulation

- Appendix

- Bibliography

- Index