- 616 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This third edition of Straight and Level thoroughly updates the previous edition with extensive comments on recent industry developments and emerging business models. The discussion is illustrated by current examples drawn from all sectors of the industry and every region of the world. The fundamental structure of earlier editions, now widely used as a framework for air transport management courses, nonetheless remains unchanged. Part 1 of the book provides a strategic context within which to consider the industry's economics. Part 2 is built around a simple yet powerful model that relates operating revenue to operating cost; it examines the most important elements in demand and traffic, price and yield, output and unit cost. Part 3 probes more deeply into three critical aspects of capacity management: network management; fleet management; and revenue management. Part 4 concludes the book by exploring relationships between unit revenue, unit cost, yield, and load factor. Straight and Level has been written primarily for masters-level students on aviation management courses. The book should also be useful to final year undergraduates wanting to prepare for more advanced study. Amongst practitioners, it will appeal to established managers moving from functional posts into general management. More broadly, anyone with knowledge of the airline industry who wants to gain a deeper understanding of its economics at a practical level and an insight into the reasons for its financial volatility should find the book of interest.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Straight and Level by Stephen Holloway in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART 1

Strategic Context

When your strategy is deep and far-reaching, then what you gain from your calculations is much. When your strategic thinking is shallow and near-sighted, then what you gain from your calculations is little and you lose before you do battle. Therefore victorious warriors win first and then go to war, while defeated warriors go to war first and then seek to win.

Sun Tzu

One point of view is that industry economics are our master, determining what can and cannot be done. Less deterministically, we can take the view that an understanding of industry economics is a tool which allows managers to work towards the vision they have for their airline’s future and to meet the more explicit objectives established by stakeholders such as customers, employees, shareholders, alliance partners and members of the wider community. This book takes the latter approach. The single chapter in the opening part of the book outlines a customer-oriented strategic framework within which the understanding of industry economics developed in subsequent chapters can be applied.

1

Strategic Context

Never be afraid to try something new. Remember, amateurs built the ark; professionals built the Titanic.

Anonymous

CHAPTER OVERVIEW

Most airlines have a competitive strategy embodying the type of value they intend delivering. Its choice of competitive strategy is reflected in each carrier’s operating strategy. The performance associated with an operating strategy depends on revenues earned from delivering expected benefits to targeted customers and on costs incurred delivering those benefits.

Part 2 of the book will look at airline revenues (traffic × yield) and costs (output × unit cost).

Part 3 will focus on key aspects of capacity management, which is in many respects the critical operations management challenge because it lies at the interface between cost and revenue streams.

Part 4 looks at several key macro-level metrics of operating performance.

What this opening chapter does is outline the strategic context within which costs and revenues are generated. It begins by identifying the scale of the challenge. It goes on to look at the theoretical underpinnings of the important but sometimes ill-defined concepts of ‘strategy’ and ‘business model’. It then examines the changes currently taking place in airline business models. It ends by describing in more detail the structure of the book.

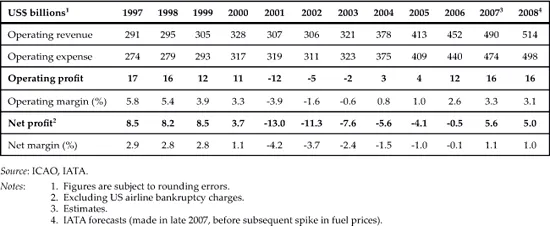

I. The Scale of the Challenge

Airlines have annual revenues of approximately half a trillion dollars and employ over 2 million people. They directly support another 2.9 million jobs at airports and civil aerospace manufacturers, and may indirectly support in excess of 15 million jobs in tourism (Air Transport Action Group 2005). Low-fare airlines in Europe are alone estimated to contribute close to half a million direct, indirect, and induced jobs (York Aviation 2007). The air transport industry, at the heart of which lie airlines, directly contributes US$330 billion per annum to world GDP (ibid.) and underpins as much as US$3.5 trillion (i.e., around 8 per cent) if direct output is aggregated with output generated elsewhere in the industry’s supply chain, with the multiplier effect of corporate and personal spending by industry participants, and with the catalytic impact airlines have on tourism, trade, and investment (IATA 2007d). Airlines carry well over 2 billion passengers and between 25 and 30 per cent by value of world trade each year, and are therefore among the primary facilitators of global economic growth. Commercial aviation in the United States is estimated to be directly or indirectly responsible for 5.8 per cent of the country’s economic activity, 5.0 per cent of personal earnings, and 8.8 per cent of employment (The Campbell-Hill Aviation Group 2006). Yet airlines, taken together, have historically been unable to cover their cost of capital (Pearce 2006). Table 1.1 illustrates the scale of the problem.

Although many carriers outperform industry averages and a handful generate returns which do exceed their cost of capital (e.g., Ryanair and AirAsia), the industry as a whole has not been capable of sustaining profitability throughout an entire economic cycle. At the end of 2007, the top of the most recent up-cycle, the industry remained almost $200 billion in debt and earned a net margin of little more than 1 per cent. A normally competitive industry would be expected to earn its cost of capital, but the airline industry has yet to achieve this. The problem has been particularly acute in the United States. Reviewing the period from deregulation in 1978 until 2005, Heimlich (2007) observes that:

• the median US airline net margin was -0.4 per cent, compared with 5.2 per cent for all US corporations;

• in their best year the airlines achieved a net margin of only 4.7 per cent, compared with 9.1 per cent for all corporations;

• in their worst year the airlines’ net margin was -10.3 per cent, against 3.1 per cent for corporations generally;

• there was accordingly a 15-point spread for the airlines, as opposed to 6 points for all corporations.

By the end of 2005 the US airline industry had, according to the Air Transport Association (2007), made a cumulative net loss of US$16.8 billion since 1947. Clearly, the airlines most responsible for this performance have had to endure considerable strain on their balance sheets; many entered Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, some on more than one occasion, and several have been liquidated.

Whilst the failings of senior management and the obduracy of labour have undoubtedly contributed to the economic downfall of particular airlines, the fact that underperformance has been so widespread across the industry over such a long period of time implies that there are structural impediments at work. The purpose of this book is to explain the nature of the challenge accepted by anybody responsible for an airline’s income statement, and in doing this highlight the structural changes currently taking place in the industry. Because ‘strategy’ and ‘business model’ are concepts which are prominent in the discourse of change, and because they establish the context within which the economics of the industry are explained in subsequent chapters, the next section will briefly define them.

Table 1.1 Summary of airline profits and margins 1997–2008

II. Strategies and Business Models: Some Theory

STRATEGY

‘Our strategy is to be the low-cost provider.’ ‘Our strategy is to provide unrivalled customer service.’ ‘Our strategy is to be number one or number two in all our markets.’ What each of these statements has in common is that none of them describes a strategy. They describe elements of a strategy (Hambrick and Frederickson 2005). Strategy can never be about service, price, output or cost in isolation; it has to address all of them in a coherent manner. There are many different definitions of strategy, but one which is compelling in both its simplicity and its information value states that ‘effective strategy is a coherent set of individual actions in support of a system of goals’ (Eden and Ackermann 1998, p. 4) [emphasis added].

Goals and the actions taken to achieve them will often be specified in detailed plans, but some of what is planned will inevitably fall by the wayside whilst alternatives emerge unplanned from the dynamics of the marketplace to augment or replace original intent (Mintzberg 1994). What is constant in any effective strategy, however, is a theme. According to Grant (1998, p. 3), ‘Strategy is not a detailed plan or program of instructions; it is a unifying theme that gives coherence and direction to the actions and decisions of an individual or organization.’ Porter (1996, p. 71) argues that, ‘In companies with a clear strategic position, a number of higher-order themes can be identified and implemented through clusters of tightly linked activities.’

Whether the above definition is applied at the corporate, divisional or functional level, there should be a coherent theme uniting strategic action. But what is ‘strategic’? The word has been devalued, often being used as a synonym for ‘important’. To be truly ‘strategic’ an action must reinforce or change one or more of the following:

• the scope of the corporation’s portfolio of businesses;

• the market (or ‘horizontal’) scope of an individual business in the portfolio;

• the value offered to customers of an individual business;

• the competitive advantage sought by a business;

• the operating strategy used by a business to deliver value to its customers.

These dimensions of strategy will be considered briefly in the context of the airline industry.

Corporate Strategy: The Industrial Scope Decision

The industrial scope decision addresses which businesses a corporation should be investing in. It is the essence of ‘corporate’, as different from ‘competitive’, strategy. During the 1970s and early 1980s, portfolio planning matrices such as the Boston Box, the McKinsey Directional Policy Matrix, and the Arthur D. Little Life-Cycle Matrix were widely used to help structure industrial scope decisions (Bowman and Faulkner 1997); their underlying logic was to search continuously for ways to rebalance the corporate portfolio by investing free cash flow from slow-growing mature businesses into faster-growing new businesses. Since the late 1980s, emphasis has shifted towards analysis of shared competencies and the search for a better understanding of how it is that aggregating different businesses within the same corporate group actually creates more shareholder value than would be created were each independent; this has contributed to a move away from conglomerate diversification.

In the context of the airline industry, the industrial scope decision is a matter of whether and, if so, how far to diversify away from the air transport business. The decision might result in one of three group structures for an airline or its holding company:

1. Single business This is the model adopted by carriers concentrating on air transportation as their core business and outsourcing all activities considered ‘non-core’ relative to the carriage of passengers and cargo. Air transportation services might be offered using a single brand across all markets served, or a suite comprised of a master-brand and separately sub-branded ‘production platforms’. For example, the JAL Group comprises master-brand Japan Airlines and sub-brands JALways, JAL Express, J-Air, Japan Asia Airways, and Transocean Air.

2. Portfolio of related businesses This model includes in addition to air transport operations a number of divisions, subsidiaries, and/or joint ventures in fields related to air transport. How to define ‘relatedness’ is an open question, but generally we would expect related businesses to share inputs, technology, competencies, and/or markets and to reap economic benefits from this sharing. Whilst some airlines (e.g., British Airways) have for many years been focusing primarily on air transport operations, others (e.g., Lufthansa and Singapore Airlines) have been developing activities related to air transport into significant independent revenue-generators. Lufthansa made a strategic decision in the 1990s to diversify in order to reduce reliance on volatile earnings from passenger air transportation: it created Lufthansa Technik, Lufthansa Cargo, Lufthansa Service, and Lufthansa Systems, which within a decade together accounted for approximately 40 per cent of group revenue. Separately, several European charter airlines and Canadian carrier Air Transat are themselves a part of vertically integrated portfolios of related businesses within the leisure travel value chain.

3. Portfolio of unrelated businesses Most airlines and airline holding companies are now less inclined than some have been in the past to involve themselves in activities only tenuously related to air transport; All Nippon has stepped back from the hotel business, for example, but Icelandair’s holding company has not. A few carriers, particularly in Asia where there is still a penchant for conglomerate diversification, are themselves part of broad industrial portfolios (e.g., Asiana, Cathay Pacific, EVA Air, and Kingfisher).

The corporate strategies of different airlines or airline holding companies can be outlined by using comparative bar charts to map the percentages of total revenue attributable to different businesses within their portfolios. Our interest in this book is limited to the economics of air transport businesses.

Competitive Strategy: Horizontal Scope, Customer Value, Competitive Advantage, And Operating Strategy

Airline managers do not confront the economics of the industry in a vacuum, but within the context of a particular competitive strategy. Competitive strategy is behaviour intended to build and/or leverage a competitive advantage. Each business, whether it stands alone or is part of a broader portfolio, should have a competitive strategy. The essence of a competitive strategy can be found in the answer to four questions that will be considered in the next four subsections: In which product and geographical markets should we compete? What value will we offer to targeted customers (or, more crudely, who would care if we ceased to exist and why)? How will we create and sustain an advantage over our competitors in each of those markets? How should we profitably organize the production of output to deliver the desired value to customers in targeted markets and to exploit our competitive advantage?

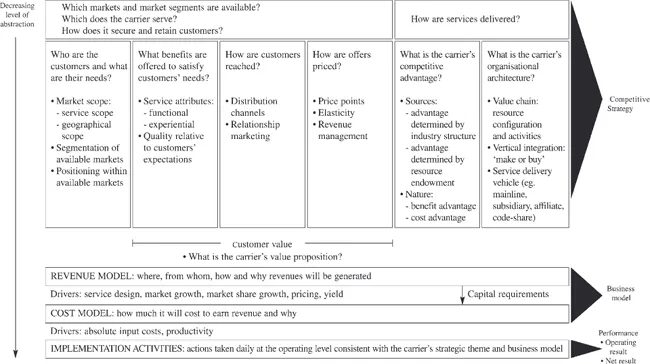

Figure 1.1 illustrates, at a generalised level, how competitive strategy might be formulated and how it relates to the concept of a ‘business model’. The elements identified are all discussed below and will be encountered again in subsequent chapters; the purpose of this framework is to provide a context that can be referred to as necessary when reading through those chapters.

Horizontal scope: in which markets should we compete? Purchase of air transportation involves simultaneous participation in both a geographical market and a service market (Holloway 2002).

1. Geographical scope can be:

• Wide-market There are several large international airlines, but no truly global carriers. Again, different production platforms may be used to serve different geographical markets; alliances are intended in part to broaden geographical scope within the constraints of both industry economics and the prevailing international aeropolitical regime – a regime which, as we will see in Chapter 4, is still on the whole relatively restrictive in some parts of the world but is rapidly liberalising in most major markets. An airline’s network is, in fact, now widely perceived as a core attribute of its service – hence the imperative felt by many network carriers to build alliances.

• Niche This involves offering either a wide or a narrow range of services into a small number of geographical markets. What constitutes a geographical niche and what represents a geographical wide-market strategy is obvious at the extremes (e.g., regional carriers on the one hand and the US ‘Big Three’ on the other), but unclear in the middle ground. A large number of the world’s international airlines make wide-market service offers into a relatively limited range of geographical markets, and are in this sense ‘geographical niche carriers’ – although they might not think of themselves as such. Many have moved out of geographical niches by joining global alliances; those that choose not to make this move will need confidence that they have distinctive and sustainable cost and/or service advantages with which to defend their niches. At the other end of the spectrum Belgian carrier VLM, bought by Air France-KLM in 2008, successfully established a geographical niche linking London’s business-oriented City Airport to near-continental destinations and UK provincial centres. Similarly, US carrier Allegiant Air was established to link relatively small communities to Las Vegas and Florida, tapping into thin vacation markets lacking intense competition. And at the time of writing, 23 of the 39 destinations served by Spirit are in the Caribbean and Latin American regions – a deliberate reorientation away from increasingly competitive domestic US markets.

Figure 1.1 Relationships between competitive strategy, business model and performance

Choice of geographical scope is clearly a fundamental underpinning of any airline’s competitive strategy. In the mid-2000s, for example, bmi began to shift the emphasis of its mainline operations at London Heathrow away from short- and towards medium- and long-haul routes. Most US network carriers are growing their international operations in preference to expanding domestic output. In both cases this shift in geographical scope has been a response to intensifying competition from low-fare airlines, and further downward pressure on yields, in short-haul markets.

2. Service scope – the targeting of specific segments of demand within geographical markets, members of which want particular combinations of price and product – can be:

• Wide-market A portfolio of passenger and cargo transport services is offered by a single carrier, either under its sole corporate brand or using a mixture of mainline, divisional, subsidiary, and/or franchised sub-brands to target distinct segments of demand.

• Niche A single type of service, or a very narrow range, is offered. A typical example would be a low-fare carrier offering single-class service to one or a relatively narrow range of segments. Another would be a European charter carrier, offering single-class service to tour organizers and seat-only retail purchasers. The premium-only long-haul airlines which began operations in 2005 and 2006 provide examples at the other end of the service–price spectrum (e.g., Eos, Silverjet, L’Avion). ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations and Definitions

- Foreword by Maurice Flanagan

- Preface

- PART 1 STRATEGIC CONTEXT

- PART 2 OPERATING PERFORMANCE DRIVERS

- PART 3 CAPACITY MANAGEMENT

- PART 4 OPERATING PERFORMANCE

- References

- Index