- 238 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Where collaboration is needed and silo working creates barriers to achieving this, the cost to organisations can be very high: a lack of shared learning and innovation; unproductive conflict and stress; and significant financial costs due to programme failures. Collaborating for Results focuses on the human reasons for unproductive silo working in organisations, combining psychology with broader organisation development theory and practice. The central theme is that a visible agenda for building and maintaining working relationships across organisations is required by those seeking competitive advantage. It describes the contours of working relationships at three levels - individual, team and organisation - and proposes practical actions en route to collaboration and high performance. In doing so it acknowledges the complexity of people and relationships, the interrelationship of the three levels and explains the value of developing Open Teams at the heart of an integrated approach to business and organisational development. Organisation silos can feel like different countries, or even parallel worlds. Even in a single organisation, people in separate divisions or teams can talk a different language and have different work cultures that they each find difficult to understand and relate to. David Willcock's Collaborating for Results reframes organisation culture to bridge the divide, develop working relationships that save time and money and improve organisation performance.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Collaborating for Results by David Ian Willcock in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

The Individual and the Organisation

1

Factors that Influence Behaviour

You are in a Silo

We are all in silos at the same time as being connected with each other; it’s a natural state of affairs.

As a human being I have a physical boundary to the outside world. My contact with the environment is mediated by my senses (touch, taste, smell, sight, sound, feelings) and the sense I make of these through my beliefs, values and self-concept – my ‘sense of self’. I can choose to be in contact or out of contact with others. I can include or exclude myself. I can move towards people, away from them or against them. I can be more or less open with other people in how I communicate. I can try to control, be equal or be submissive. My face can be fixed or relaxed. I can be rigid, flexible or somewhere in between. What balance I strike in my contact with others will be based on several factors including those which I now describe.

MY PHYSICAL HERITAGE

My physical heritage is the inherited genetic makeup and the physical disposition I am born with. This will influence my level of physical and psychological comfort or discomfort and therefore the choices I make. Genetics and physical disposition are outside of the scope of this book, although it is important to recognise their influence on our psychological makeup. My focus is on the social and psychological domains and the behaviour of people to explain silo working and how to improve the quality of relationships people have. You cannot change the spots on a leopard, but you can influence how it behaves!

MY PSYCHOLOGICAL TYPE

This is a deep seated disposition that influences my preferences for relating to the world through extroversion or introversion and the basic psychological functions of thinking, feeling, sensing and intuition. I draw on the work of Carl G. Jung (1921) to explain this.

MY UPBRINGING AND SOCIAL CONDITIONING

By this I mean how I have experienced and responded to the environmental and social influences in my life, such as living conditions, parenting and education. These are the learned patterns of behaviour that have helped me to survive and grow. How this learning can potentially help or hinder our relationships with others is outlined in Part I.

MY PERSONALITY TRAITS

These are the core dimensions of my personality, or character, that have influenced and been influenced by all of the above. For example, the degree to which I am trusting or sceptical, controlling or accommodating. I draw on the work of the psychologist Raymond B. Cattell (1946) and many psychologists who have followed him to provide insights in this area.

MY SELF-AWARENESS AND MANAGEMENT

This is the degree to which the above influences are conscious to me and within my control. It is the sense of identity or ‘self’ that I develop and how I manage the boundaries between being ‘me’ and ‘not me’. My values are part of this ‘self-awareness’ and a way of managing the boundary between ‘me’ and ‘not me’.

MY AWARENESS OF AND EMPATHY FOR OTHER PEOPLE

This determines the degree to which I take an interest in other people and relate to their experience based on my own.

THE CONTEXT I FIND MYSELF IN RIGHT NOW AND THE SENSE I MAKE OF IT

This is my perception and understanding of the ‘here and now’ reality of what is going on. For example, waiting for the green light at a road junction, or noticing how upset I feel about someone else’s comments.

MY SKILLS AND CAPABILITIES

These are the social, interpersonal and other skills and capabilities that I have developed to present myself and influence other people.

WHAT I WANT/NEED RIGHT NOW

This is about the need I have to satisfy in my current situation. At its most basic, this might be a physical need to quench a thirst which leads to me drinking water. Other needs or desires are psychological, such as love, recognition and control. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is a good descriptor of the needs we have at different levels of experience (Maslow 1987). My need in the current context is the key determinant of the nature of the contact I will make with others. The quality of that contact will depend on how I try to satisfy that need against the background of all of the influences above and the situation I find myself in.

This list of factors is a kaleidoscope of interactive influences and is not exhaustive.

The nature and quality of contact we regularly make with others can be called our character or ‘personality’. Part nurture, part nature, we develop patterns of thinking, feeling and behaving that we apply to different situations. We learn and develop through our contact with others and the wider environment, both shaping and being shaped by them. In its healthiest form, this is a reciprocal relationship that leads to growth and development that can continue throughout a lifetime (Capra 1997). We are never too old to learn if that is what we choose to do. As we know, however, this paints an ideal picture and there is a lot of interference in our relationships with others that leads to misunderstanding, conflict, avoidance and sometimes breakdown.

Chapters 2 and 3 cover some of the interference and how it hinders good quality relationships between individuals in organisations. First I explain more how some of the fundamental elements of personality outlined in this section are described and how they influence the way we behave, focusing on Psychological Type, traits, the desires we have at different stages of relationship development and the beliefs and values we hold.

My purpose here is not to give you an in-depth understanding of personality and personality dimensions or to train you in the use of personality questionnaires. What I want to demonstrate is how these dimensions of personality are a key aspect of the nature of differences between people and the relevance of this to how people behave, working relationships and silo working.

Psychological Type – The Foundations of Personality

Type theory was developed in the early part of the twentieth century by Carl G. Jung (1921), a psychiatrist and student of Sigmund Freud. Jung’s ideas are based on his observations of ‘typical’ differences in normal behaviour over many years both in and out of a clinical setting.

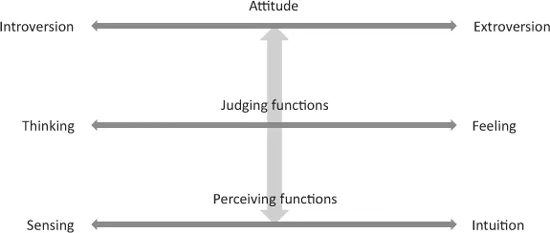

Jung distinguished between what he called ‘attitude types’ and ‘function types’. The attitudes are ‘introverted’ and ‘extroverted’ – terms that Jung introduced and are now common to us. The functions are the basic psychological functions of thinking, feeling, sensing and intuition.

The extroverted person is primarily orientated towards the objective outer world of people and things. The introverted person is primarily orientated towards their subjective inner world and how they perceive and make sense of things.

Sensing and intuition are perceiving functions – how you take information in. People with a sensing preference will take information in through the senses of sight, sound, touch, smell and sensations. They tend to prefer a focus on the facts and here and now reality. They tend to be practically minded and desire to keep things simple. People with an intuitive preference tend to use their ‘sixth sense’ and like novelty and variety. They tend to like exploring possibilities and may like the complex and theoretical.

Thinking and feeling are judging functions – how you make decisions based on the information you have. People with a thinking preference will tend to make judgements based on objective logic. Those with a feeling preference will tend to be more subjective, basing decisions on personal values, particularly in relation to people.

The four basic psychological functions may either be extroverted or introverted, depending on the prevailing attitude. According to Jung there is also a hierarchy of function depending on the disposition of the individual – people have preferences for thinking or feeling, sensing or intuition. This results in an order of preference, for example dominant ‘thinking’ supported by secondary ‘intuition’ with ‘feeling’ and ‘sensing’ as third and fourth preference. Jung believed that one function tended to dominate to the neglect of others.

Jung subscribed to the idea that we all need to find psychological ‘equilibrium’, or balance in life. He viewed attitudes and functions as balancing ‘opposites’, a bit like yin and yang, night and day. According to Jung, a conscious extrovert attitude will be balanced automatically by an unconscious introverted attitude. A dominant thinking function will be balanced by unconscious feeling, sensing by intuition and vice versa. To achieve balance we can potentially access all of these attitudes and functions. However, people vary in the degree to which they acknowledge and pay attention to the non-dominant functions and therefore in the balance they achieve. This has implications for personal development and also the management of differences between people with opposite preferences.

Figure 1.1 shows a way of representing the attitudes and functions, recognising their opposing and balancing positions:1

Figure 1.1 Psychological Type – attitudes and functions

The different possible combinations of attitudes and functions means there are a number of possible Type differences between people.2

In the context of silo working and collaboration there is clearly potential here for creative use of differences or misunderstanding and possible conflict. This is explored further in the next chapter.

Jung viewed Psychological Type as a deep seated and possibly physiological disposition, something you are potentially born with. He believed it transcended class, gender and nationality. This is the main reason I began this chapter on personality with Psychological Type. It has a strong influence from an early age on the way we respond to life’s experiences. It influences the journey we make in life, how we develop, our career choices, our interests. It is fundamental to understanding diversity. It helps us understand how we can make the most of our differences and what some of the root causes of relationship difficulties are.

There are personality inventories available to identify people’s Type preferences, the original and most widely used being the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI®).3 This was developed after the Second World War by Isabel Briggs Myers and her mother, Katherine Briggs. She wanted to find a way to help people avoid destructive conflict – something Jung was also deeply interested in. Isabel Briggs Myer’s book, Gifts Differing, is a wonderful insight into Jung’s Type theory and the MBTI® inventory, including further researched development of Psychological Type theory (Myers and Myers 1995). The MBTI® and other Psychological Type indicators are used extensively in organisations throughout the world to help people understand type differences and improve working relationships. Used in the right way they can help to reduce silo working and improve collaboration.

Traits – The Building Blocks of Personality

Personality traits can be defined as the underlying and enduring characteristics of an individual, the combination of which strongly influence their pattern of behaviour in different circumstances. Jung’s Psychological Types was the first attempt at developing a framework for classifying differences and similarities between people. What Jung referred to as a ‘typology’. Raymond B. Cattell (1946) was the psychologist who first developed a framework to describe personality traits.4

Traits are common to us. We refer to them all the time when talking about people. We say people are ‘moody’, ‘excitable’, ‘well balanced’, ‘shy’, ‘confident’, ‘sensitive’ and ‘tough minded’. There are hundreds of personality traits that we could describe and each one can be of a different strength, more or less characteristic of a person. So some people are more confident, shy, sensitive or tougher than others.

The different combinations of these traits and trait strength influence character and behaviour – creating distinct personalities. So someone who is independent may also be socially confident and warm-hearted. They may for example be gregarious when collecting information, but then make a decision on their own. Someone who likes to work in groups or teams may also be intellectually confident and emotionally stable. They may be able to remain objective in a discussion and conduct a good analysis of the facts rather than being swayed by group opinion. Richard Branson can be described as a radical free thinker and adventurous at the same time as very grounded and informal in his approach. Alan Sugar can be described as tough-minded, realistic and self-assured whilst also being calm, serious and principled.

Building on Cattell’s original work (Cattell 1946), psychologists have researched and developed a number of different yet overlapping personality trait frameworks to assess personality. These include the Sixteen Personality Factor Questionnaire (16PF®), Fifteen Factor Questionnaire Plus (15FQ+™) and the Neuroticism, Extraversion and Openness Personality Inventory (NEO PI-R®).5 These, and many other multi-factor personality questionnaires, can be viewed as different ways of sub-dividing the ‘Big Five’ personality dimensions. The Big Five are the major areas identified by many psychometric researchers (see for example Goldberg 1990). The language and definitions differ slightly between psychometric frameworks, but in broad terms they describe the degree to which people are:

• socially introvert or extrovert;

• emotionally secure or more anxious;

• pragmatic or more open to experience;

• independent or more cooperative;

• unconstrained or more self-controlling.

These dimensions are general expressions of personality that will be recognisable to many of you. We often talk of the ‘extroverted’ or ‘introverted’ person, the anxious person or the nice, accommodating person. People can have different strengths of tendency on these dimensions. So for example people are more or less introverted, pragmatic or cooperative.

The strength of tendency on these five general dimensions of personality is influenced by lots of other underlying character traits as well as Psychological Type (for example, introversion and extroversion). Example descriptions of some underlying traits for each of the main five dimensions are given in brackets:

• Introvert (reserved, shy, autonomous) or extrovert (empathic, energetic, gregarious).

• Emotionally secure (balanced, trusting, confident) or anxious (reactive, suspicious, worried).

• Pragmatic (objective, practical, conservative) or open to experience (attentive, sensitive, challenging).

• Independent (assertive, self-confident, questioning) or more cooperative (accommodating, tolerant, dependent).

• Unconstrained (flexible, spontaneous, free-thinking) or more self-controlling (responsible, discreet, principled).

The words in brackets also show that character or personality can be viewed as something more ‘fluid’ rather than as a result of enduring trait combinations. Every aspect of character has possible multiple dimensions or polarities (Zinker 1978). So cruelty can have a polarity of kindness, warmth and merciful. Kindness can have polarities of ruthless, cold and vindictive. There is a whole range of strength of characteristics between these and other possible dimensions. What we are capable of acce...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- About the Author

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations1

- Reviews for Collaborating for Results

- Part I The Individual and the Organisation

- Part II The Team, Other Teams and the Organisation

- III The Organisation

- Bibliography

- Index