- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

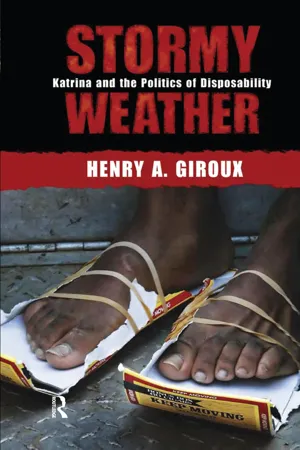

"By far the single most important account and analysis of the Katrina catastrophe." David L. Clark, McMaster University In his newest provocative book, prominent social critic Henry A. Giroux shows how the tragedy and suffering in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina signals a much larger crisis in the United States-one that threatens the very nature of individual freedom and inclusive democracy. This crisis extends far beyond matters of leadership, governance, or the Bush administration. It is a crisis that strikes at the very heart of democracy and must be understood within a broader set of antidemocratic forces that not only made the social disaster underlying Katrina possible, but also contribute to an emerging authoritarianism in the United States. Questions regarding who is going to die and who is going to live are driving a new form of authoritarianism in the United States. Within this form of "dirty democracy" a new and more insidious set of forces-embedded in our global economy-have largely given up on the sanctity of human life, rendering some groups as disposable and privileging others. Giroux offers up a vision of hope that creates the conditions for multiple collective and global struggles that refuse to use politics as an act of war and markets as the measure of democracy. Making human beings superfluous is the essence of totalitarianism, and democracy is the antidote in urgent need of being reclaimed. Katrina will keep the hope of such a struggle alive because for many of us the images of those floating bodies serve as a desperate reminder of what it means when justice, as the lifeblood of democracy, becomes cold and indifferent.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Stormy Weather by Henry A. Giroux in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Ciencias sociales & Sociología. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

◊

1

Katrina and the Biopolitics of Disposability

When it thunders and lightnin' and when the wind begins to blowWhen it thunders and lightnin' and the wind begins to blowThere's thousands of people ain't got no place to go—Bessie Smith

Emmett Till's body arrived home in Chicago in September 1955. White racists in Mississippi had tortured, mutilated, and killed the young 14-year-old African-American boy for whistling at a white woman. Determined to make visible the horribly mangled face and twisted body of the child as an expression of racial hatred and killing, Mamie Till, the boy's mother, insisted that the coffin, interred at the A. A. Ranier Funeral Parlor on the South Side of Chicago, be left open for four long days. While mainstream news organizations ignored the horrifying image, Jet magazine published an unedited photo of Till's face taken while he lay in his coffin. Shaila Dewan points out that “[m]utilated is the word most often used to describe the face of Emmett Till after his body was hauled out of the Tallahatchie river in Mississippi. Inhuman is more like it: melted, bloated, missing an eye, swollen so large that its patch of wiry hair looks like that of a balding old man, not a handsome, brazen 14-year-old boy.”1 The Jet photos not only made visible the violent effects of the racial state; they also fueled massive public anger, especially among blacks, and helped to launch the Civil Rights Movement.

From the beginning of the Civil Rights Movement to the war in Vietnam, images of human suffering and violence provided the grounds for a charged political indignation and collective sense of moral outrage inflamed by the horrors of poverty, militarism, war, and racism—eventually mobilizing widespread opposition to these anti-democratic forces. Of course, the seeds of a vast conservative counterrevolution were already well under way as images of a previous era—“whites only” signs, segregated schools, segregated housing, and nonviolent resistance—gave way to a troubling iconography of cities aflame, mass rioting, and armed black youth who came to embody the very precepts of lawlessness, disorder, and criminality. Building on the reactionary rhetorics of Barry Goldwater and Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan took office in 1980 with a trickle-down theory that would transform corporate America and a corresponding visual economy. The twin images of the young black male “gangsta” and his counterpart, the “welfare queen,” became the primary vehicles for selling the American public on the need to dismantle the welfare state, ushering in an era of unprecedented deregulation, downsizing, privatization, and regressive taxation. The propaganda campaign was so successful that George H. W. Bush could launch his 1988 presidential bid with the image of Willie Horton, an African-American male convicted of rape and granted early release, and succeed in trouncing his opponent with little public outcry over the overtly racist nature of the campaign. By the beginning of the 1990s, global media consolidation, coupled with the outbreak of a new war that encouraged hyper-patriotism and a rigid nationalism, resulted in a tightly controlled visual landscape—managed both by the Pentagon and by corporate-owned networks—that delivered a paucity of images representative of the widespread systemic violence.2 Selectively informed and cynically inclined, American civic life became more sanitized, controlled, and regulated.

Since the 1990s there has been a drying up of images that make the violence of war, poverty, and racism visible in the United States. The domestic war of images largely won, the administration of George H. W. Bush retooled for the war abroad. Learning a lesson from the Vietnam War, it tried to control both the style of the news and the release of visual images that accompanied the reporting of the Gulf War in 1991. Unpleasant images of the war were either censored or white-washed. Under the auspices of the Defense Department and a corporate media all too willing to do the government's bidding in exchange for further deregulation by the FCC, the concept of war was aestheticized. Soldiers framed against the backdrop of a blazing sunset replaced mangled bodies and bloodied wounds. Air strikes were morphed into video games, and images of battle were craftily packaged by the advertising gurus of the government-friendly public relations firm Hill and Knowlton. Increasingly, the public's right to know was replaced with an official policy of misrepresentation, distortion, and secrecy. The National Security Archive acknowledges that “[t]he practice of permitting media coverage of fallen soldiers' return to the United States was curtailed in 1991, during the Gulf War.”3

Within a decade, the American visual landscape had once again been utterly transformed. The multiracial make-up of the George W. Bush administration succeeded in selling the lie of a race-transcendent, color-blind, and meritocratic nation, effectively silencing critical inquiry and debate over widening racial inequality and injustice in mainstream political coverage. Why meet with the NAACP, the president once quipped, when he sits in daily meetings with Colin Powell and Condoleezza Rice? With domestic race relations a dead issue, with the single exception of affirmative action, which he condemns, President Bush and his minions focused their energies on managing the second Gulf War. The anti-democratic confluence of censorship and secrecy has become one of the Bush administration's defining and vigorously defended principles. Once again, the Pentagon resurrected the practice of prohibiting photographs of the flag-draped caskets of the dead returning from war. With the advent of the Internet, representations of the bodies of mangled civilians, children, and others who are not soldiers can be found on Al Jazeera and other alternative media sites, especially in the Middle East and Europe, but are rarely seen in the mainstream media in the United States. This visual absence is further reinforced by the government's Orwellian language of collateral damage, often disappearing into a state- and media-sponsored fog of secrecy and censorship. Instead of providing images of the real consequences of war, the Bush administration and the dominant media present images of the Gulf War that offer viewers a visual celebration of high-tech weaponry and earthy down-home grit on the part of American soldiers. President George W. Bush's initial bombardment of Baghdad was introduced to the public through the metaphor of “shock and awe,” one that prioritized slick advertising over human suffering and offered up representations of the attack modeled after a giant Fourth of July fireworks display. “Embedded” reporters were often transformed into daring postmodern cowboys riding in armored tanks, fitted with the latest high-tech weapons and photographed against pristine images of the desert, producing war images in which immediacy replaced context. Modeled on the familiar Reality TV show, media representations of the war celebrated the ethos of militarism, obedience, discipline, and technological mastery. Theatricality replaced substance, and aesthetics triumphed over politics.4 Representations of war and violence were increasingly staged as a global spectacle, diminishing the critical functions of sound, image, and language along with the critical capacities of viewers. But there was more at work here than the residual return of a kind of fascist aesthetics. There was also the struggle over representations of agency, masculinity, patriotism, and national values.

In many ways, the second Iraq war, as Bill Moyers pointed out, has become a “war of images.”5 When Ted Koppel, host of the television show Nightline, announced that he was going to read the names and show pictures of the U.S. soldiers who had died in Iraq (721 as of that day), Sinclair Broadcasting, owner of no fewer than sixty-two television stations, blacked out the faces and names when the program aired on its ABC affiliate stations. According to the Sinclair Broadcast Group, Koppel's actions were deemed subversive and unpatriotic and “would undermine public opinion.”6 Even when the war's positive-image brigade hit a rough patch with the scandal at Abu Ghraib, the media barely blinked. The editor of the New York Post announced after the 60 Minutes II story “shocked the world with photos of U.S. military personnel abusing and torturing Iraqis” held in Abu Ghraib prison that “he would not run the photos because ‘a handful of U.S. soldiers’ shouldn't be allowed to ‘reflect poorly’ on the 140,000 who do their job well.”7 Political-image management took a major hit with the publication of the Abu Ghraib prison photos. Government officials played down the incident, claiming it involved only a handful of soldiers and refusing to release additional images they had confiscated. With now-characteristic gall, a few supporters of the Bush administration, such as Republican Oklahoma Senator James Inhofe, claimed that the real problem was not the acts of abuse and torture at Abu Ghraib but the liberal media's decision to release such images to the public. Of course, Seymour Hersh and a number of other journalists later proved that the horrendous abuses and tortures at Abu Ghraib were neither limited to one prison nor merely the result of a few “bad apples.”8 As is now commonly known, such practices were justified at the highest levels of government. Tragically, as disturbing as these pictures were, they were never fully represented and understood “as part of the dynamic of military culture and the experience of war” against populations of color.9 This particular breach of Pentagon control seems to have exhausted its capacity for mobilizing either collective reflection or outrage and social action.

In a few instances over the last two decades, individual citizens used new media technologies to challenge this type of collective censorship and made public some of the deeply disturbing and defining contradictions shaping American life. For instance, a videotape made in 1992 of the vicious beating of an African-American man, Rodney King, by four Los Angeles police officers shattered the conservative discourse about color-blindness, the end of racism, and the media's utter complicity with the residual force of the racial state.10 More recently, as new media technologies such as the Internet, digital photography, and electronically mediated forms of communication emerge and convey information at a higher velocity than ever before, it has become more difficult to prevent disturbing images and photographs from reaching the American public. As David Simpson points out, “It is not news that all images are subject to both direct and self-imposed political control. Private Jessica Lynch, for example, had the independence of mind to resent the falsifications of her captivity narrative for propaganda purposes and the courage to say so.”11 Unfortunately, she was quietly dropped from any major media attention when she exposed the government's fabricated lie about her capture in Iraq.

Hurricane Katrina may have reversed the self-imposed silence of the media and public numbness in the face of terrible suffering. Fifty years after the body of Emmett Till was plucked out of the mud-filled waters of the Tallahatchie River, another set of troubling visual representations has emerged that both shocked and shamed the nation. In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, grotesque images of bloated corpses floating in the rotting waters that flooded the streets of New Orleans circulated throughout the mainstream media. What first appeared to be a natural catastrophe soon degenerated into a social debacle as further images revealed, days after Katrina had passed over the Gulf Coast, hundreds of thousands of poor people—mostly blacks, some Latinos, many elderly, and a few white people—packed into the New Orleans Superdome and the city's convention center, stranded on rooftops, or isolated on patches of dry highway without any food, water, or any place to wash, urinate, or find relief from the scorching sun.12 Weeks passed as the flood water gradually receded and the military gained control of the city, and more images of dead bodies surfaced in the national and global media. TV cameras rolled as bodies emerged on dry patches of land where people stood by indifferently eating their lunch or occasionally snapping a photograph. The world watched in disbelief as bloated decomposing bodies left on the street—or, in some cases, on the porches of once-flooded homes—were broadcast on CNN. Most of the bodies found in the flood water “were 50 or older, people who tried to wait the hurricane out.”13 A body that had been found on a dry stretch of Union Street in the downtown district of New Orleans remained on the street for four days, “locked in rigor mortis and flanked by traffic cones. [It quickly] became a downtown landmark—as in, turn left at the corpse—before someone” finally picked it up.14 Responding to this human indignity, Dan Barry, a writer for the New York Times, observed: “That a corpse lies on Union Street may not shock. … What is remarkable is that on a downtown street in a major American city, a corpse can decompose for days, like a carrion, and that is acceptable.”15 Alcede Jackson's 72-year-old black body was left on the porch of his house for two weeks. Various media soon reported that over 154 bodies had been found in hospitals and nursing homes. The New York Times wrote that “the collapse of one of society's most basic covenants—to care for the helpless—suggests that the elderly and critically ill plummeted to the bottom of priority lists as calamity engulfed New Orleans.”16 Dead people, mostly poor African-Americans, left uncollected in the streets, on porches, and in hospitals, nursing homes, electric wheelchairs, and collapsed houses, prompted some people to claim that America had become like a “Third World country” while others argued that New Orleans resembled a “Third World Refugee Camp.”17 There were now, irrefutably, two Gulf crises. The Federal Emergency Management Agency tried to do damage control by forbidding journalists to “accompany rescue boats as they went out to search for storm victims.” As a bureau spokeswoman told Reuters News Agency, “We have requested that no photographs of the deceased be made by the media.”18 But questions about responsibility and answerability would not go away. Even the dominant media for a short time rose to the occasion of posing tough questions about accountability to those in power in light of such egregious acts of incompetence and indifference.

The images of dead bodies kept reappearing in New Orleans, refusing to go away. For many, the bodies of the poor, black, brown, elderly, and sick came to signify what the battered body of Emmett Till once unavoidably revealed, and America was forced to confront these disturbing images and the damning questions behind the images. The Hurricane Katrina disaster, like the Emmett Till affair, revealed a vulnerable and destitute segment of the nation's citizenry that conservatives not only refused to see but had spent the better part of two decades demonizing. But like the incessant beating of Poe's tell-tale heart, cadavers have a way of insinuating themselves on consciousness, demanding answers to questions that aren't often asked. The body of Emmett Till symbolized an overt white supremacy and state terrorism organized against the threat that black men (apparently of all sizes and ages) posed against white women. But the black bodies of the dead and walking wounded in New Orleans in 2005 revealed a different image of the racial state, a different modality of state terrorism marked less by an overt form of white racism than by a highly mediated displacement of race as a central concept for understanding both Katrina and its place in the broader history of U.S. racism.19 That is, while Till's body insisted upon a public recognition of the violence of white supremacy, the decaying black bodies floating in the waters of the Gulf Coast represented a return of race against the media and public insistence that this disaster was more about class than race, more about the shameful and growing presence of poverty, “the abject failure to provide aid to the most vulnerable.”20 Till's body allowed the racism that destroyed it to be made visible, to speak to the systemic character of American racial injustice. The bodies of the Katrina victims could not speak with the same directness to the state of American racist violence, but they did reveal and shatter the conservative fiction of living in a color-blind society.

The bodies that repeatedly appeared all over New Orleans days and weeks after it was struck by Hurricane Katrina laid bare the racial and class fault lines that mark an i...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- 1. Katrina and the Biopolitics of Disposability

- 2. Dirty Democracy and State Authoritarianism

- Notes

- Index

- About the Author