- 183 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Both born to power and wealth, and raised by courtiers, they lived lives of aristocrats and landowners, in poor health and with uncertain futures. Though they lived over 3000 years apart, the lives of Egyptian King Tutankhamun and the fifth Lord Carnarvon share many parallels, not the least of which was Carnarvon's sponsorship of the team that found the pharaoh's tomb in the Valley of the Kings. Brian Fagan's narrative expertly weaves these two lives together, showing similarities and differences between these two powerful men. -Both figures are placed in their historical context, showing the political and social machinations of 18th Dynasty Egypt and 20th century archaeological exploration in Egypt.-Grounded in historical and archaeological research, the two figures are made to come alive as real people.-An Afterword by the author shows archaeologists how to tell research stories that are accessible to a wider audience.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Lord and Pharaoh by Brian Fagan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

A Valley of Pharaohs

Horus, Mighty Bull, Beloved of Truth

He of the two ladies, Risen with the fiery serpent, Great of strength

Horus of gold, Perfect of years, He who makes hearts live

He of the sedge and bee Aakheperkara [Upper and Lower Egypt]

Son of Ra Thutmose living forever and eternity.1

Egyptian pharaohs, glorified by their imposing titles, presided over the longest-lived state of the ancient world, which endured for over three thousand years after the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt in about 3100 B.C. Centuries of precedents and rituals surrounded the divine ruler that was the pharaoh. He (and occasionally she) was the embodiment of the Egyptian state, beloved by the sun god Ra, and a person apart from mere mortals. His or her subjects approached the throne prostrating themselves seven times, then seven times more. The pharaohs were divine monarchs who assumed that their deaths were merely a step from their rule on earth to continued kingship in the realm of eternity. Their tombs were portals to the underworld, carved below the earth as a gateway to their glorious immortality alongside the sun god. Hundreds of artists and craftspeople labored over royal sepulchers, filling them with magnificent treasures and adorning the walls with exquisite reliefs and paintings that reflected an elaborate cosmology and religious philosophy. For five centuries after 1539 B.C., the pharaohs constructed their tombs in a remote, dusty valley known today as The Valley of the Kings.

The Valley of the Gate of the Kings

The rulers lay in an inconspicuous but magnificent burial ground that is now one of the most famous archaeological sites in the world. Its location has never been a mystery, for the Ancient Egyptians themselves ransacked the royal sepulchers in ancient times. The Greek geographer Strabo visited Upper Egypt in 25 B.C. and wrote of the west bank opposite what is now Luxor that “above the Memnonium [the mortuary temple of Ramesses II] are tombs of kings, which are stone-hewn, are about forty in number, are marvelously constructed, and are a spectacle worth seeing.”2 By Roman times, Egypt was a popular tourist destination. At least two thousand graffiti left by Greek and Latin visitors adorn ten Valley tombs with prominent entrances.

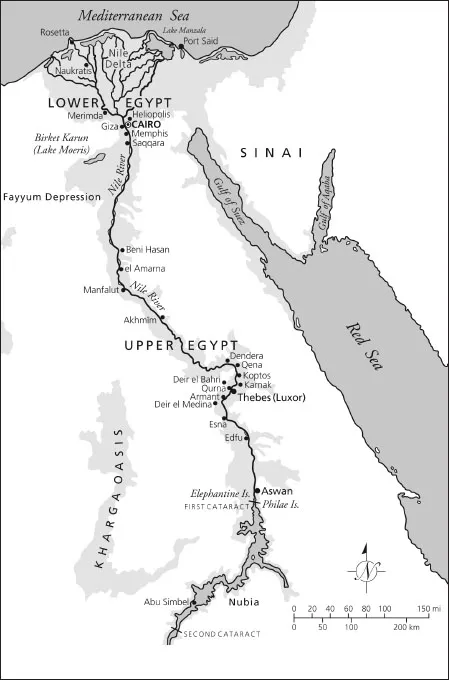

Figure 1.1 Map of Egypt showing major locations mentioned in the text.

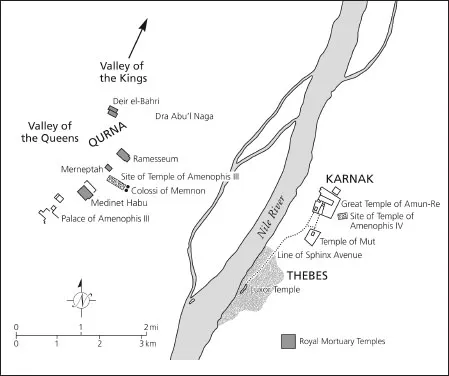

Figure 1.2 Thebes, ancient Waset, the realm of the dead being on the west bank.

Wadi Biban el-Muluk (“The Valley of the Gates of the Kings”) lies on the west bank of the Nile, opposite Waset (Thebes), now Luxor, “The Estate of Amun.”3 Here, the great temples of the creator god Amun at Karnak and Luxor were settings for public ceremonies and processions. Every year during the second month of the early summer flood, the Opet festival saw the boatlike shrine of Amun process from Karnak to Luxor, proclaiming that the king had renewed his ka, or spiritual essence, in the innermost shrine of Amun himself. The great temples were statements of raw imperial power, where the gods received food offerings and found shelter. Amun’s temples owned cattle and mineral rights and maintained enormous grain stores. The wealth of the large temples and the authority of their gods were such that the great shrines were a major factor in the economy—and a significant presence in the affairs of state. All the myths and rituals, as well as the imposing temples, were symbols of the continuity of proper rule, of ma’at, “rightness,” a philosophical concept absolutely central to Egyptian thinking and pharaonic rule.

Figure 1.3a The Valley of the Kings in the early twentieth century. © Griffith Institute, University of Oxford.

The Estate of Amun encompassed the western bank. A flat plain extended from the river opposite Thebes to rocky hills laced with shaded gullies, an area associated by the Egyptians with the setting sun and the afterlife. The god’s estate was a symbolic way of extending the notion of continuity into the realm of the dead in the west. Here the pharaohs created an elaborate necropolis, a city of the dead, where mummified, or at least bandaged, commoner and noble alike lay in a confusion of mortuary temples and sepulchers. Common folk lay in narrow clefts and defiles in the rocky hills, with perhaps an amulet or two in their wrappings. The elite in their multiroomed sepulchers could afford elaborate sarcophagi and all the panoply of mummification to ensure immortality in the Underworld. The pharaohs embraced eternity with elaborate mortuary temples among the sepulchers of commoners and nobles, all dedicated to Amun-Re and lay in splendidly furnished underground tombs, cut into the rock of the Wadi Biban el-Muluk.

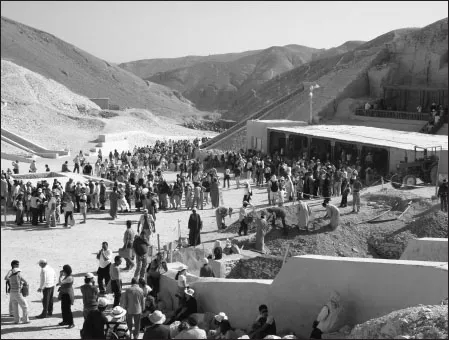

Figure 1.3b The Valley of the Kings today. From Markh from en.wikipedia.

The mountains to the west of the great river were where the sun set, the realm of death. And it was in their shadow that the pharaohs constructed their underground sepulchers. Wadi Biban el-Muluk is a dry river valley of eroded slopes and small dry water courses. A pyramid-shaped peak dominates the much-eroded defile, sacred to the goddess Hathor, guardian of the cemeteries on the west bank of the Nile. The first pharaoh to be buried in the Valley was probably Tuthmosis I, in about 1518 B.C., who apparently decided to separate his mortuary temple from his burial place.4 For the next five centuries, the pharaohs of the Eighteenth, Nineteenth, and Twentieth Dynasties (1539–1075 B.C.) built their rock-cut tombs in the Valley. The ravine was remote and easily guarded, but its symbolic position was all-important. The hills behind the west bank formed the horizon of the setting sun, the realm of death. The main, eastern branch of the Valley, known to the Egyptians as te set aat (“The Great Place”) contains most of the royal sepulchers. The purpose was common to all, but the lavish decoration and rich furnishings reflected not only the exquisite craftsmanship of royal artisans but also the rich philosophical beliefs of an ever-changing civilization.

Geologically, Wadi Biban el-Muluk is a complex place, its topography much eroded by rare, intense rainstorms. The light brown rocks of the Valley are mainly limestone with underlying layers of shale, relatively soft formations that made it easier for tomb workers to carve rock-cut sepulchers deep into bedrock. To the pharaohs, death was merely a step in the transition from ruling on earth to being a king in the immortality of the underworld. Royal tombs were portals to this realm as well as nether regions themselves, places built totally underground according to long-established precedent. When not crowded with visitors, they can be mystical, even scary, places. Many years ago, when fewer people were around, I visited the Valley while lecturing on a package tour. We paused for a break, so I slipped away from everyone and went into the tomb of Ramesses III. The lights were on, so I walked rapidly into the depths of the sepulcher, knowing that time was short. As I reached the burial chamber, the lights went out. The utter darkness and stillness settled around me like a blanket. The effect was mesmerizing. I’m not exaggerating when I say that I could literally feel the presence of the pharaoh. Then the lights went on and the spell was broken. I had briefly glanced into the underworld of eternity.

For all its profound ritual ambiance, the Valley of the Kings was a vast underground treasure house, with riches beyond imagining there for the taking. Ruthless tomb robbers emptied many of the sepulchers within a few generations. Later came treasure hunters, tourists, and finally archaeologists, the latter in search of the ultimate Holy Grail—an undisturbed pharaoh’s tomb.

Belzoni’s Tomb

When the Romans departed, the Valley faded into oblivion, the tombs inhabited by a few Christian hermits.5 Over the centuries, it remained a remote defile of scree-laden hillsides, dry gullies, and cliffs. It’s hard to imagine the Valley as it was as recently as the 1920s. Today there are booths and coffee shops, paved roads, parking lots for coaches, and restrooms. Wadi Biban el-Muluk has become a popular tourist destination, jammed with package tours and confused visitors. You wait in lines to inspect those tombs that are open to the public.

Only the occasional traveler explored the royal burial ground until the nineteenth century, among them an Englishman, Richard Pococke, in 1730. He thought that he identified about eighteen tombs, only nine of which could be entered. In 1768, Scottish traveler James Bruce described frescoes of harpists in Ramesses III’s tomb, which he illustrated with fanciful abandon. The Valley was a remote curiosity until Napoléon Bonaparte invaded Egypt in 1798, his idea being to secure a strategic passage to India across the Isthmus of Suez. He took with him 140 savants, under the leadership of Vivant Denan, charged with describing Egypt, ancient and modern. For three years, a diminishing number of scientists traveled the Nile alongside the 4,000-man army. Savant and soldier alike gasped in admiration at the temples of Luxor and Karnak, at a hitherto unknown civilization quite unlike those of Greece and Rome. Denan accompanied a military party to the Valley of the Kings. To his intense frustration, he was allowed a mere three hours to examine six tombs. While he returned to France with Napoléon in 1799, his fellow savants embarked on a survey of Egypt that was to appear in the multivolume Description de l’Égypte, one of the classics of Egyptology. The Description contained the first systematic map of the Valley, which recorded sixteen tombs and, in the western arm, the beautiful tomb of Amenophis III.

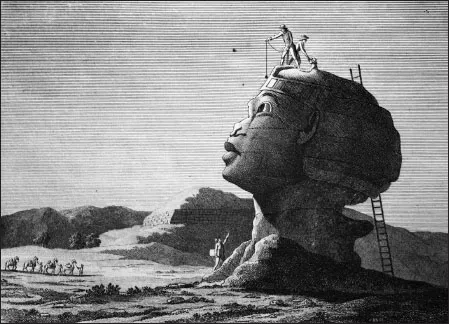

Figure 1.4 Napoléon’s savants examine the Sphinx at Giza (from Description de l’Égypte). Vivant Denon, 1830.

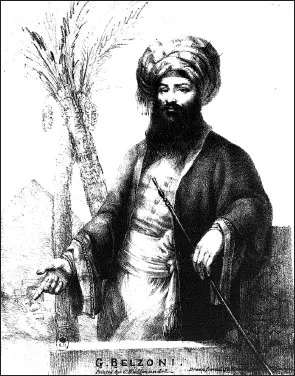

Napoléon’s savants revealed the astounding glories of Ancient Egypt and set off an aggressive search for Egyptian antiquities, notably in the hands of the French and British consuls, the Piedmontese-born Colonel Bernardino Drovetti and Henry Salt, a more scholarly diplomat. Both saw it as part of their charge to collect antiquities and sell them to major European museums. The competition was intense. The two men laid claims to most of the Estate of Amun. Drovetti dug frantically accompanied by his gang of what might charitably be called ruffians. Salt employed one of the most remarkable figures to work in the Valley of the Kings—Giovanni Belzoni. He became Drovetti’s deadly rival. Blows were exchanged, guns threatened. Both were quite capable of lying in wait for a competitor with a gun.

Padua-born Giovanni Battista Belzoni was an imposing figure, who stood well over 2 meters (6 feet). Women are said to have found his curly black hair and broken English accent irresistible. As a young man, he sold religious relics across Europe, then became a circus performer and strongman in London. The “Patagonian Sampson” became a minor celebrity, famous for his achievements of strength and stagecraft. Years of show business gave Belzoni an expertise with weights, levers, and gunpowder, which was to serve him well along the Nile. He came to Egypt in 1815, accompanied by his long-suffering Irish wife Sarah, looking for work mechanizing agriculture and failed abysmally. In desperation, he accepted an offer to collect antiquities for Henry Salt. Belzoni was the ideal person for the job. Quite apart from his engineering skills, he was adept at dealing with the local people. He also seems to have possessed a rare quality, an instinct for archaeological discovery. The professional tomb robbers of the village of Qurna in the Theban Necropolis took a liking to the tall strong man, who enjoyed meals with them, the food cooked with broken mummy cases as firewood. Belzoni followed them into narrow, mummy-packed defiles. Fortunately, he had no sense of smell, but he complained that “mummies were rather unpleasant to swallow.”

Figure 1.5 Giovanni Belzoni in Turkish costume. From Narrative of the Operations and Recent Discoveries Within the Pyramids, Temples, Tombs and Excavations in Egypt and Nubia by Giovanni Battista Belzoni, London, 1820.

Belzoni came to the Valley of the Kings in 1816, well aware that the Romans had said there were as many as forty-seven tombs in the Valley. Belzoni counted ten or eleven that he considered to be royal sepulchers and began by puttering around the western arm, where he soon found the tomb of the courtier turned pharaoh Ay, who was to play an important role in Tutankhamun’s life (see Chapter 5). But the Paduan was after much more important prey—royal tombs. In August 1817, he returned to the western arm and soon concluded that there was nothing to find, and so he moved into the Valley of the Kings itself. In October, he set twenty men to work in small groups, working in different places. Four days later, he found the sepulcher of Prince Mentuherkhepeshef, Hereditary Prince, Royal Scribe, Son of Pharaoh, Beloved by Him, Chief Inspector of Troops.6 The tomb (KV 19) is remarkable for its painted scenes of the young prince in the presence of the gods.

Then it rained, a rare occurrence in Thebes. Torrents of floodwater cascaded down a slope close to the emptied tomb of Ramesses I (KV 16), which Belzoni had found a short time earlier. Convinced there was another tomb nearby, Belzoni set his men to work. Two days later, a cutting in the rock appeared. Five-and-a half meters (18 feet) below the surface, a tomb entrance emerged from the rubble. Eventually, one of the smallest workers was able to crawl under the lintel. He emerged into two richly decorated corridors, a flight of stairs, and an open pit. Belzoni had discovered the most magnificent sepulcher in the Valley (KV 17), that of the pharaoh Seti I, father of Ramesses II, who had died around 1300 B.C.

As he crawled through the first rubble-strewn passage, Belzoni saw great vultures hovering above them. Down the stairway, the Sun God lurked in all his flamboyant manifestations. His solar boat journeyed through the fourth division of the underworld on the right. On the left it entered the fifth hour, drawn by gods and goddesses. Everything ended at the pit with a wall beyond, a sump for flood waters as well as a device to mislead tomb robbers. In that it failed, for there was a hole on the opposite side.

The next day, Belzoni returned with two stout beams to bridge the pit. He squeezed through the robber’s hole and found himself in a pillared hall with magnificent figures of the pharaoh being embraced by deities and scenes of the underworld. A false chamber beyond adorned with deliberately unfinished figures aimed to deceive robbers, but failed to do so. Belzoni and his men tapped the walls and broke through to another corridor that led eventually to the burial chamber. The art on the walls entranced Belzoni with its mastery, but it was nothing compared with the six-pillared burial chamber with the deities and forces of the underworld, the Sun God’s b...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- 1. A Valley of Pharaohs

- 2. Discoveries of a Self-Made Man

- 3. Effective for the Aten

- 4. A Gambler with Enthusiasms

- 5. Tutankhamun the Justified

- 6. “The Records of the Past Are Not Ours to Play With”

- 7. Restorer of Amun

- 8. The Search Narrows

- 9. Death of a Pharaoh

- 10. “I Have Got Tutankhamun!”

- 11. Aftermath

- 12. “Let Me Tell You a Tale”: A Chapter for Archaeologists

- Appendix A: A Chronological Framework of Ancient Egypt

- Appendix B: A Short Guide to the Pharaohs of the XVIII to the XX Dynasties Mentioned in the Narrative

- Further Reading

- Notes

- Index

- About the Author