eBook - ePub

World of Workcraft

Rediscovering Motivation and Engagement in the Digital Workplace

- 178 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Research demonstrated some years ago that there is a strong positive correlation between 'play', 'fun' and organisational performance. More recently, organisations have started to wrestle with the idea of how to engage the skills and motivation of the video game generation; as customers and as employees. The practical application of gamification is part of the disruptive innovation that offers businesses radical new ways of working, learning and performing. In a nutshell, gamification is the concept of applying engaging elements of game theory to non-game applications. An example would be to create a game to learn something new for work. Companies need to embrace the idea of blending games with work. And in order for that to happen, gamification must have a basic knowledge base and skill set, as well as both theory and practical application of its core principles. Dale Roberts's World of Workcraft provides the context and background to the need for and potential benefit of gamification as a means of turning a traditional corporate culture and structure into a dynamic community. He also provides guidance on how to (and how not to) introduce these concepts successfully.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access World of Workcraft by Dale Roberts in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Work and Play

Chapter 1

Game Changer

The Game

The neologism gamification was introduced in 2002 by British consultant Nick Pelling to describe how his business at the time, Conundra, developed electronic devices that were more like entertainment platforms. Only much later did it come to describe software rather than hardware, supplanting other terms such as funware that didn’t gather the same momentum. Somewhat ironically, Pelling intended it to be an ugly word. For this he should be awarded maximum points, given the ‘Mission Accomplished’ badge and placed at the top of the leaderboard for awkward neologisms. It’s a genuine ugly duckling, growing up to be a swan in 2011, when it was runner-up for the Oxford English Dictionary word of the year, after which it stuck. However, its acceptance is by no means certain. Many pioneers in this field still use the term reluctantly, and others, particularly the growing number of gamification software vendors, actively avoid using it with their customers for fear that the flippant phrase will diminish what they do. The term invites hype from some and frequent predictions that it is ‘game over for gamification’ from others.

However, gamification is much more than a word only its mother could love. Behind the inelegant phraseology is a set of underlying principles that are certain to gain momentum and widespread usage as the discipline matures and becomes better understood.

Gamification or whatever word that may or may not ultimately replace it is the use of elements we usually associate with fun and games to motivate, engage and change our behaviours in situations that are not games. But where did the idea originate? What’s behind its becoming rapidly and widely discussed, and what’s its potential to change our lives at home and at work?

The Badges

• Causal Cadet

• Digital Interventionista

• Fitness Coach

• Human Seller

• Moonshooter

To Know the Cause of Things

On a frosty February evening, I stood outside the New Academic Building of the London School of Economics (LSE), admiring the stone-crafted motto ‘rerum cognoscere causas’, or ‘to know the causes of things’. It’s also the name of a course that’s compulsory for all LSE undergraduates, to introduce them to the fundamentals of thinking like a social scientist, examining the ‘big’ questions like ‘How do we manage climate change?’, Is population growth a threat or an opportunity?’ and ‘Who caused the financial crisis? It was fitting to be hosted by an institution that has, at its core, a grounding in examining important issues through different lenses.

I was waiting for the rest of a group of gamifiers, a London-based network of designers, consultants, writers and entrepreneurs involved in the world of gamification. At this stage, some readers may still be bristling at the words ‘gamifiers’ and ‘gamification’ even after understanding their origins. These synthetic terms may still be provoking a reaction that the nature of gamification is itself an altogether unnatural construction. Professor Kevin Werbach, Associate Professor at the Wharton School and co-author with Dan Hunter of For the Win, describes gamification as ‘the use of game elements in a non-game context’. And it’s this, rather than the word itself, that for many is jarring. Games, and particularly video games, are strictly leisure. They’re a distraction or an escape. They have no place in the ‘real world’. It makes no sense to weld game elements onto things that are not games. Like the world-renowned Ubon restaurants introduced by Nobuyuki Matsuhisa and Robert De Niro, who fused Japanese with Peruvian food, it shouldn’t work. Except it does. And there’s growing evidence to suggest that, when implemented correctly, it works well.

Eventually, when our group of gamifiers was quorate, we were ushered into a wood-panelled room by a team of masters students. The team were working on a project for an undisclosed bank to investigate the use of gamification to encourage children to develop a responsible attitude to money and savings.

The group had been invited to help shape the direction of the project. Whilst the bank was clearly an early innovator in this space, this wasn’t the first group to think about the financial literacy of young people. The mobile game Green$treets: Unleash the Loot! was created by US author Neale Godfrey to do the same thing. Under-tens can earn money by completing chores, and can spend money in a marketplace on their mission to rescue and care for animals. They can also choose to save money in the Green$treets bank to pay for more expensive items later. The game sends progress notification emails to parents or carers so that adults can reinforce learning as it happens, and therefore at the point when their children will be most interested. Our group had been asked to inform the project with insights into what drives engagement in gaming and what it is that makes some games so compelling that their appeal is glibly described as ‘addictive’. In addition, we identified which games attract children and the efficacy of educational games. Inputs came thick and fast from the group and from multiple perspectives. The various lenses of design, engineering, financial and commercial provided lively debate. A subsequent session drilled deeper into motivations. The group discussed and ranked the relative importance of game mechanics, which included reward, content, progression, community and customisation for two age ranges: one aged 7–12, and the other 13–16. The group also shared their experiences of existing games and how engaging they are, to identify whether the product should be influenced by elements found in, say, Monopoly or FarmVille.

In addition to the input from the community of gamifiers, the LSE team devised an online poll to harvest the opinions and ideas of others, including parents, on what they thought might be the best way to motivate children to learn about positive money management. As was fitting for the subject matter, this group of LSE masters students had complemented traditional approaches with contemporary digital ones, including connecting, crowdsourcing and co-creating with online communities.

Digital Interventions

Only a few weeks after the sessions with LSE, I joined a group in a very different setting. At the centre of London’s ‘Silicon Roundabout’ is a Google facility which has all of Shoreditch’s rich history on the outside, but is all industrial chic on the inside. This group meeting here, the largest such group in the UK, were a truly multidisciplinary lot. Sociologists, clinicians, healthcare consultants and biologists mixed with designers, technologists and entrepreneurs, all dedicated to debating how to bring about positive societal change using similarly technological and networked techniques. This group, District Health, are interested in the usage of technology as an enable for behavioural change in healthcare. They don’t use the word ‘gamification’, at least not any more. The group, formerly known as Gamify Your Health, prefer the term ‘digital intervention’. Their vision is to improve health by helping the nation live the adage ‘prevention is better than cure’. Their experience is that healthcare costs less the further away from hospital it’s delivered. It’s also best for us as individuals. In his book Zen Habits, former journalist and blogger Leo Babauta makes a commonsense point about living healthily. If you don’t live and eat well, if you regularly indulge in fatty, greasy, salty or sugary foods, then you’ll almost certainly have higher healthcare needs over time. That means frequent visits to the pharmacist, the doctor’s surgery, the hospital, even the operating theatre. Being unhealthy is, amongst other things, a complication that we would all be better off without. The District Health group want to find innovative new ways to help individuals create healthier habits, and to have fun in the process.

Today’s theme is a somewhat sensitive one. At first blush – and there’s an intended pun here – it would seem unlikely that we can intervene with technology to influence what is one of the most basic of human drives. We’re debating how to promote the use of condoms among those young men who fall into the socio-economic group most likely to engage in risky sexual activity.

An insight into a previous project, the website Sexunzipped and some unsettling insights into the rising rates of sexually transmitted infections immediately raise the energy level in the room. Nervous, salacious, childish or prurient thoughts are displaced by the seriousness of the subject and the forthright and intelligent introduction to the session from Dr Julia Bailey from University College London. As is common with gamification projects, we first establish a persona – a profile, sometimes called a player type, that describes the target group for the intervention. Our persona is James. James is 19, Afro-Caribbean, lives in a poor inner-city area in London, and would describe himself as ‘very heterosexual’. His mum, proud and hardworking in our extended persona description, would be extremely upset if James became a father too early. She believes in social mobility, and has aspirations for James that include further education, a profession and material success outside of her own experiences.

Persona established and debated, we quickly get on to the design workshops. Eight or nine groups of four people around the room focus on interventions that might normalise condom usage, deal with the perceived reduction in pleasure, and address the embarrassment associated with buying and using condoms. The air is alive with debate. In our group and the groups around us there are questions, like ‘How do we help young women confidently veto sex without condoms?’, ‘How do we help young men not to feel undermined by discussions about condom size?’ and ‘How can we encourage young men and women to be prepared before the “moment” without them being labelled promiscuous?’ Ideas are thrown around like confetti. One group settles on a mobile phone app that will allow young men to use their mobile phone camera to measure their penis, recommend their condom size, and offer statistics that assure them that their machismo isn’t undermined whatever their dimensions. Another group debate a geolocator app that immediately identifies those in a bar or club who have identified themselves as prepared and sexually responsible by carrying protection and making this status visible. Other ideas are formed and shaped in the room until there’s a wall full of Post-it Notes that will later be voted on. Any one of these ideas may later be developed into an interactive questionnaire, website, mobile app or other digital intervention to modify one of the strongest, most vital and compelling human drives.

Gamification Origins

Both these initiatives are about future projects – two of many examples of growing corporate, government and academic interest in how the use of digital interventions and gamification can influence customers, citizens and society to promote profit, civic-mindedness and the greater good. Such interest stems from the rise of high-profile online and mobile gamified systems. However, the principles aren’t really new. Gamification has been with us since at least 1981, the year American Airlines launched a programme that’s still very much alive and well today: AAdvantage.

Tom Stuker, a 59-year-old trainer, can testify to this. His prize for winning this particular game is an almost complete absence of queuing. On 6 December 2012, on a flight from London to Chicago on United Airlines, Stuker reached 1,000,000 miles in a single year. United’s Premier Elite status requires travellers to fly 100,000 miles in a year. Stuker had achieved that and, as United’s top flier, he also had a total of 13,000,000 miles under his belt, which he undoubtedly keeps buckled just in case of turbulence. Interestingly, in an interview with Joe Sharkey for the New York Times, Stuker was obviously keeping an eye on his rival, Fred Finn, a British expatriate in his early seventies who has flown 15,000,000 miles. He warns Finn to look over his shoulder, because he intends to overtake him within a couple of years. Like George Clooney’s Ryan Bingham in Jason Reitman’s film Up in the Air, it’s not entirely clear whether Stuker collects the miles because he flies, or whether he flies because he collects the miles.

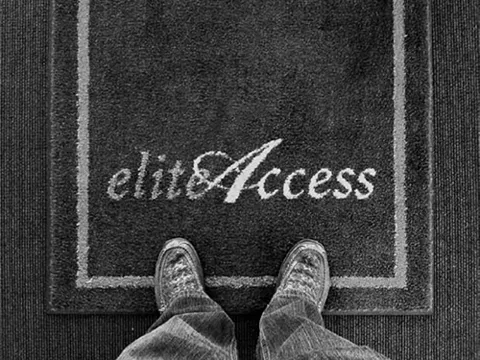

Figure 1.1 Frequent flyer

Source: Creative Commons, Larry Johnson, ‘Ten toes over the line … Elite Status!’, September 2010. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/.

Stuker isn’t alone, of course. Around 120 million people are collecting frequent flyer miles. They’re earning points. Those who are particularly good at collecting points in a set period, usually annually, will ‘level up’. For Virgin Atlantic’s Flying Club, this means moving from red to silver and then on to the top-tier world of gold. Stuker is an example of how much the colour of a card and a change in status represented by free on-board cocktails and special check-in arrangements can motivate us to choose one provider over another at what may be increased personal and financial cost.

Thirty years on, and frequent flyer programmes continue to leverage game elements such as points and levels in a way that has changed very little, yet they remain a potent marketing device. The use of status, associated with being an elite flyer or an American Express Black Card holder, has become increasingly sophisticated and has splintered into endless varieties. I’m a frequent user of the location-based social and mobile app Foursquare, and I was genuinely excited to have unlocked the ‘Warhol’ badge after checking into the Tate Modern’s Lichtenstein Retrospective in February 2013. I was equally thrilled when I unlocked a ‘Zoetrope’ badge for checking in to ten movie theatres, a ‘Jobs’ badge for checking in at three different Apple retail stores, and a ‘Banksy’ badge which required not only that I attended the movie Exit Through the Gift Shop, but that I also mentioned Banksy in my status update. Foursquare later reinvented badges when it split its applications into Foursquare and Swarm, but these small, imaginatively crafted personal achievements make counting miles seem primitive by comparison.

Habit-changing

Frequent flyer schemes and Foursquare are examples of gamified marketing and the use of game mechanics to influence our habits as consumers. The same approach can be used to rail against a sedentary lifestyle.

A typical working day for me involves nothing more strenuous than mouse clicks and eye strain. Like many in similar jobs of a similar age, I run. These days, I find it relaxing, meditative and enjoyable. I return from a weekend run brimming with energy and positively glowing. However, it wasn’t always this way. It required me to build new habits, fresh patterns of positive behaviour. Like all new behaviours, it was at first uncomfortable and hard to keep up. What helped was something that increased my engagement in this new activity that was also a lot of fun. In the Preface, I described an app, Zombies, Run!, which was as familiar to the District Health group as it was to me – part audiobook, part fitness monitor, part zombie chase game. The imaginary threat of an untimely end as an entree for al fresco zombie diners helped me past the difficult stage after the first couple of weeks, where persistence is required to make it a permanent lifestyle change.

Not everyone requires extreme motivations such as an untimely and horrible death to achieve their personal best. Almost two million runners use Nike+ to monitor their distance, pace and calories burned. Digital rewards such as encouragement from celebrity contributors act as rewards for reaching milestones. After a workout with Nike+, runners go online, where their data has been automatically uploaded and they can track their statistics, set new goals, sign up for challenges and connect with the community of runners. Other similar applications, such as RunKeeper, Strava, Fitocracy and Run Or Else, which makes charity donations as a penalty for missed commitments, are an indication of how gamified applications have become part of our fitness regimes.

Figure 1.2 Nike+ FuelBand

Source: Creative Commons, The Pug Father, ‘Nike+ Fuelband unboxing’. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/.

An important feature of these apps is that they allow the player to be in control. The route to success is not step-by-step, prescriptive or rigid. A personal best is just that – personal. One runner might be looking to improve their pace, another distance, another to reach a target weight. Well-designed gamified applications mandate only the broadest of objectives, allow players to shape what their details and how they intend to reach them. This is one of our first clues about the appeal of gamification and how it can motivate us as individuals in a way that a gameless activity may not.

Playing Outside

Gamification is challenging the notion that games are the reason behind a generation of couch potatoes. Take Zamzee – which, like our kids’ and finance project, aims to establish early positive behaviours.

Figure 1.3 Zamzee

Source: Creative Commons, Zach Copley, ‘Fancy green lights come on when I plug it into USB’. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/.

For a one-off payment, parents are given an activity meter which fits into their children’s pockets or can be attached to their clothes. The meter automatically updates a Zamzee account with daily activities. Points (inevitably called pointz) are awarded for extra activities like attending gym class or taking the family dog for a walk. Pointz lead to ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Foreword

- Preface

- PART I WORK AND PLAY

- PART II MOTIVATION

- PART III DESIGNING FOR PEOPLE

- References

- Index