- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

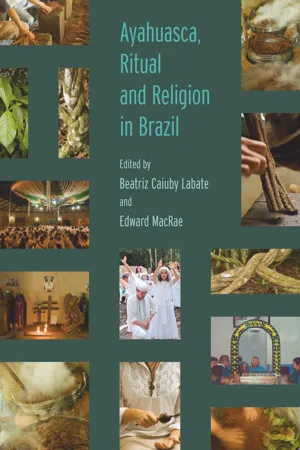

Ayahuasca, Ritual and Religion in Brazil

About this book

Ayahuasca is a psychoactive drink used for healing and divination among religious groups in the Brazilian Amazon. 'Ayahuasca, Ritual and Religion in Brazil' is the first scholarly volume in English to examine the religious rituals and practices surrounding ayahuasca. The use of ayahuasca among religious groups is analysed, alongside Brazilian public policies regarding ayahuasca and the handling of substance dependence. 'Ayahuasca, Ritual and Religion in Brazil' will be of interest to scholars of anthropology and religion and all those interested in the role of stimulants in religious practice.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ayahuasca, Ritual and Religion in Brazil by Beatriz Caiuby Labate,Edward MacRae in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The use of ayahuasca among rubber tappers of the Upper Juruá*

Mariana Ciavatta Pantoja and Osmildo Silva da Conceição

Translated by Robin Wright, revised by Matthew Meyer

Translated by Robin Wright, revised by Matthew Meyer

Testimony of Osmildo Silva Da Conceição (taped in January, 1996)

I came to hear about this brew from the oldest people, I was about nine years old. I was always curious to get to know it, but it wasn't easy to find. But when God promises, He may be late but He never fails. So there were many friends who I got to know, of those who are still alive, those who have died, and they were adults like I am today and they were already taking this brew, called ayahuasca, the name used by the rubber tappers and the Indians too. I came to know a fellow named Crispim, he was one of the strong shamans who lived here on the Extractivist Reserve, and Sebastiao Pereira, who was also one of the most experienced, who came out of this rubber camp before it became a Reserve, and they didn't forget to pass on the teachings they had to other people.

I wanted to know this brew, I wanted to drink it, but I was a kid and my Dad was still the boss. When I got to be 14 years old, I was able to see the brew, but I still didn't have the power to drink it. The first person who I saw preparing it was Major. So that was something that wakened my ideas. People said that they drank and that they saw another life, so I wanted to drink this brew, but things didn't happen so quickly as I wanted. I was only able to have the pleasure of drinking after I got to be of age, that was in 1988, when I got to know Macedo, the first time that he came here on the Tejo River. He prepared it but we didn't get to see [have visions]. We got to feel the effects, the force, of the brew well, but there were no visions. I drank and I was curious to know, but unfortunately it didn't work out.

I really only got to see, to find myself on this brew so I could see what people were talking about, and also to believe whether it was true or not, when Macedo went to the indigenous area of the Breu River and brought it from there, prepared by the indigenous shamans, by Davi Lopes Kampa, an Ashaninka Indian, and a very powerful shaman who today no longer lives on the face of this Earth. It was also really good, but since there was little, I didn't get to see a whole lot, he only gave a little bit to each one of us. But I was pleased, I wasn't able to see anyone, but I saw many beautiful things, a lot of beauty, I felt a great deal of happiness.

After 1990, it was at the time that we were at the beginning of the creation of the Reserve, the proposal was already a strong proposal, the National Council of Rubber tappers was already in operation, and they made a proposal for Milton Nascimento to come here to get to know the rubber tappers, to get to know the Ashaninka people of the Amonea River, and I was also one of the people who was invited. And it seems to me that on that trip, I was already being guided by God. It was when I came to meet the shaman Antonio Pianko, his sons also, and I didn't have the least idea how these things were. At the time I was living another life: I drank a lot of alcohol, I didn't have the least idea of what I wanted to be, of what I wanted to make of my life. And when we came to Antonio Pianko's house, we were received very well with a lot of fireworks, I felt that there was a power there. And at night, Antonio Pianko invited us to drink kamarapi, as they say, and I was also invited. That was when I began to see how spiritual life is.

The first time I drank, nothing happened, after an hour I hadn't even felt the effects of the brew. I asked to drink more, people brought it to me, and I drank.

After another half an hour, I still felt nothing. Then I asked to repeat the dose for the third time. That was when I came to receive the energies of the divine light. That was on August 14, 1990.1 went on to really see, see the light, see and experience the vision, the beauty of life. I asked God that if this brew was from God, that He make me stay with this brew, that if it wasn't part of Him, then I would prefer to stay in the life that I was living. Because on many occasions I heard that the brew could show the reality of life, and that the person could see another life as well. Many people also said that this brew was not from God, that it was a brew from another spiritual line. So I drank it more with that intention to see if it was true, I asked God, I think with a lot of love, with a lot of worthiness also, I think that for that reason I got to see a lot of things I didn't expect to see.

The first thing I came to see was from when I was a kid, playing canoe in the rivers, running around on the grounds, playing with my brothers, my life as I was growing up and living, I saw myself in a school studying. It seemed to me that I was dreaming with life, that the brew came with such a force that I couldn't even get up to walk, but I knew that I was comfortable lying in a hammock. To me, at that moment, if God had come to take me out of where I was it would have been better. Because the visionary experience was good, I was seeing all that was beautiful and I even asked God to not take me out of that life, and so, it was because of that that I am leading the life I live today. And I also got to see even the point of being grown up, the man that I feel I am today. It was then that I also asked God to give me the capacity and the worthiness to learn to work with this brew, I wanted more and more to stay on that line.

When I came back from that trip, the indigenous people gave me some guidance. They said that one had to drink that brew with someone who had a good knowledge of it, who was used to drinking it. So it was in that sense that I too was very satisfied, knowing that these things didn't just happen, that it was something that you had to have respect for, and be really secure about. And then I went back with Milton Nascimento's people. Travelling on the Amonea River, we drank the brew on a beach, it was fantastic, and we listened to some hymns of Mestre Irineu. So it was in that sense that I saw that each person has a way of watching over this brew, each one has a way of respecting this brew, which is found not only here on the Extractivist Reserve, but in various other places as well.

At the time I went downriver with Milton Nascimento, I spent the months of August, September and October with them so as to be able to go back to the area where my people, my family was. And when I arrived, I met a brother who was already working, who had already taken cipó for the first time, and who had been taken out by a person who knew the cipó, who knew the leaf and who showed it to him. My coming back to the Reserve was more for the purpose of being together with my family, because I knew that in the city, life wasn't good for me. And when I got to my brother's house, I drank the brew he had prepared. It was good, for me, I was glad to be coming back home, meeting up with my family and with that light that was already there within as well.

So then I went on to drink ayahuasca for three more months, seeing if there was a place for me to work as well. I was following the advice of the indigenous shamans, I didn't want to make a ritual drink that I didn't have the permission to do so. Every time I drank, I was asking to work, but I still didn't have an answer, so I couldn't get into something if I wasn't certain that it was really that, that I wanted to follow. I only came to make this brew when one day I met up with shamans in my visions and they came and showed me what was the type of leaf that was right one to use, how they did it, and what was the cipó. It was then I talked with my brother, he went there, he took me along, he showed me a cipó, but he didn't tell me how to make it, but I had already seen how through a vision. So it was then that I began to prepare, really preparing ayahuasca, kamarapi. It was then that I began my story with ayahuasca.

I had heard Macedo sing hymns of Mestre Irineu, which were the things that pulled me into this life. There were hymns that I learned quickly, watching Macedo sing twice and from that I also had the power to sing because, thank God, I've always had a very good memory. After 1991, at the time of the registering of the Extractivist Reserve, I had the pleasure and satisfaction of meeting Toinho Alves, who is an adept of Mestre Irineu's church from way back when, it was he who told me the name of the brew that is being administered in the churches today, Santo Daime. So I can't forget the people of the indigenous traditions, because it was through them that I got to know it for the first time, but I also can't forget to thank the people who are in these churches, taking care of the same ritual beverage but in a different way. They have the same respect, also, as the indigenous traditions. It was more or less because of that that I decided to stay with the tradition.

My life changed a great deal, I became more obedient, I came to respect the Divine Being, all the beings that inhabit the Earth and that have to be respected as well, in the same way that I respect myself. Because I know that all beings who live have a life like I have, they have to live as well. So it's not easy to learn to work with this brew, but whoever wants to learn has to do so by being worthy. So, for that reason, I feel very honored to be in this life that I am living today.

Introduction

The use of the vine called Jagube (Banisteriopsis caapi) and the leaf called Chacrona, or Rainha (lit. 'Queen) (Psychotria viridis), which is quite common in the forests of the Jurua River valley, in the preparation of a beverage for ritual use, is inscribed in the tradition of Arawak and Panoan-speaking indigenous peoples who have, from time immemorial, inhabited the region. In this text, however, we intend to explore the history, forms of use and meaning of this ritual beverage among non-indigenous groups, more specifically the rubber tappers of the Extractivist Reserve of the Upper Juruá.

We prefer to use the name 'ayahuasca throughout this text, although we also mention other names used by rubber tappers to refer to the beverage.1 This choice of terms was made, on the one hand, because this term is sufficiently well-known and allows us to discuss the case that is narrated in this article in the context of a larger tradition. The vastness of this tradition, on the other hand, allows us to highlight the singularity of the case of the rubber tappers of the Extractivist Reserve of the Upper Juruá.

The following text is divided into four main parts: the first introduces the reader briefly to the history of occupation of the Jurua Valley by northeastern migrants who became its future rubber tappers, and their conflicts with the native populations; the second deals with the history of ayahuasca among the rubber-gathering population of the Upper Juruá; the third, the preparation of the brew; and finally, the last part is on its ritual consumption. The text also includes a statement by one of the authors on his initiation to the use of ayahuasca. The culture of ayahuasca has always spread amongst rubber tappers in the midst of great secrecy, and we shall seek to respect this spirit here.

Brief history of the recent occupation of the Juruá valley

The Juruá Valley, a vast area of rivers and forests with a large number of rubber trees, Hevea brasiliensis, is located in the far west of the state of Acre. Until 1870 exploratory expeditions were occasional and for commercial purposes, concentrating on the extraction of sarsaparilla, vanilla, copaiba balsam, rubber and other similar products, by the indigenous peoples. These products were traded for merchandise2 with Panoan and Arawak-speaking indigenous peoples, traditional inhabitants of this region, and with the 'caboclos', a name which was used to refer to the non-indigenous regional population. In the case of the Indians, many groups had been, by that time, persecuted and enslaved (see Aquino and Iglesias, 1994).

In the last decades of the nineteenth century, the continuing increase of the international demand for rubber was responsible for the opening-up of the majority of the rubber camps existing in the Juruá Valley, and for the structuring of an economy that marked the region in a decisive way In 1870, a steamboat went up the Juruá River for the first time, marking the beginning of a new era. This expansion took place through the penetration and exploration of new lands located along the courses of the rivers, claims made to their ownership, and speculation based on illegal titles (see Almeida, 1992).

The first problem to be settled was the scarcity of labor for work in the extraction of latex. The indigenous population resisted, and the conflicts were violent. Armed expeditions - called 'correrias' (incursions) - were organized which sought to decimate and expel the indigenous populations from their traditional territories, and were responsible for the extermination of several groups, or for their flight to areas in Peru where there were no rubber trees. In several cases, indigenous groups were absorbed by the rubber industry, as was the case of the Panoan-speaking Kaxinawá of the Jordão River.3 Their traditional Arawak-speaking enemies, whose population was concentrated predominantly in Peru, were at first enslaved by the 'caucheiros'4 and, after 1870, they were used by Brazilian bosses as a fighting force against the isolated Pano (Mendes, 1991).

The solution to the problem of lack of labor was the importation of workers from the Brazilian Northeast, ravaged by the drought at the end of the nineteenth century Transportation of the immigrants to the newly-formed rubber camps was financed by the supply-houses of Belém and Manaus, which were responsible for the exportation of the rubber. It is estimated that between 25,000 and 50,000 new rubber tappers migrated to Amazonia in each decade since this first rubber boom. The Juruá Valley then became one of the principal areas for native rubber production in Amazonia (see Almeida, 1992).

The Tejo River basin, where the main characters of this text lived and live today, was the jewel of the Upper Juruá. It was first occupied by rubber tappers in the last decade of the nineteenth century, and in 1900 it was being exploited up to the headwaters of the Manteiga and Riozinho streams. The opening of the Restauração rubber camp also dates to this time. In 1907, the Tejo was described as a river that was already much inhabited by rubber tappers, from its mouth, passing the Paraná do Gomes (today, the Bagé River), the Riozinho, Camaleão, Tamisa and Machadinho, and up to the Boa Hora, one of its last tributaries (Mendonça, 1989). The labor system that was then established and which made the economic exploitation of the rubber trees viable was based on the subordination of the rubber tappers to the 'bosses',5 who exercised a supposedly absolute commercial monopoly over all the rubber produced by the rubber tappers.6 Besides that, the...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- About the contributors

- Forward

- Brazilian Ayahuasca religions in perspective

- 1. The use of ayahuasca among rubber tappers of the Alto Juruá

- 2. The rituals of Santo Daime: systems of symbolic constructions

- 3. Santo Daime in the context of the new religious consciousness

- 4. The Barquinha: symbolic space of a cosmology in the making

- 5. Healing in the Barquinha religion

- 6. Religious matrices of the União do Vegetal

- 7. In the light of Hoasca: an approach to the religious experience of participants of the União do Vegetal

- 8 Ayahuasca: the consciousness of expansion

- 9. The development of Brazilian public policies on the religious use of Ayahuasca

- 10. The treatment and handling of substance dependence with ayahuasca: reflections on current and future research

- Index