eBook - ePub

From Acorns to Warehouses

Historical Political Economy of Southern California’s Inland Empire

- 283 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

From Acorns to Warehouses

Historical Political Economy of Southern California’s Inland Empire

About this book

Thomas C. Patterson's large-scale history of the Inland Empire of Southern California traces the social, political and economic changes in this region from the first Native American settlement 12,000 years ago to the present. Framing his discussion of this region in the general growth trajectory of California's socio-economic history, he is able to connect landscape, resources, wealth, labor, and inequality using a Marxian framework for many key periods of the region's history. In moving between large scale historical changes, regional adaptations and resistance to those changes, and a framework that places those responses in theoretical context, Patterson's work allows the reader to see how inland Southern California developed into the warehouse empire of the 21st century and its prospects for the future.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access From Acorns to Warehouses by Thomas C Patterson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

LIVING LANDSCAPES

The landscapes of Southern California are dynamic. They are products of the mutually interdependent and interacting processes that created them as well as of historical particularities of time and place. When people arrived, more or less fifteen to twenty thousand years ago, they too became part of the larger, mutually constitutive totality we call “nature.” They engaged in an ongoing, metaphorical dialogue, if you will, with the other constituents—a metabolic exchange mediated, regulated, and controlled by their labor. While human beings are a part of nature, they are not necessarily determinant or even dominant. Since the interplay of forces shaping the region began long before people arrived, it is important to have some appreciation of what was involved as new landscapes formed and obscured or obliterated altogether traces of earlier ones. These forces still operate.

NATURE’S SUBSTRATE

There was no California 200 million years ago. It was underwater—ocean bottom off the west coast of North America. Two processes have contributed significantly to the formation of Southern California. One is plate tectonics, the inexorable movement of gigantic plates over the earth’s surface. The other is climate change, which has local, regional, and global effects.

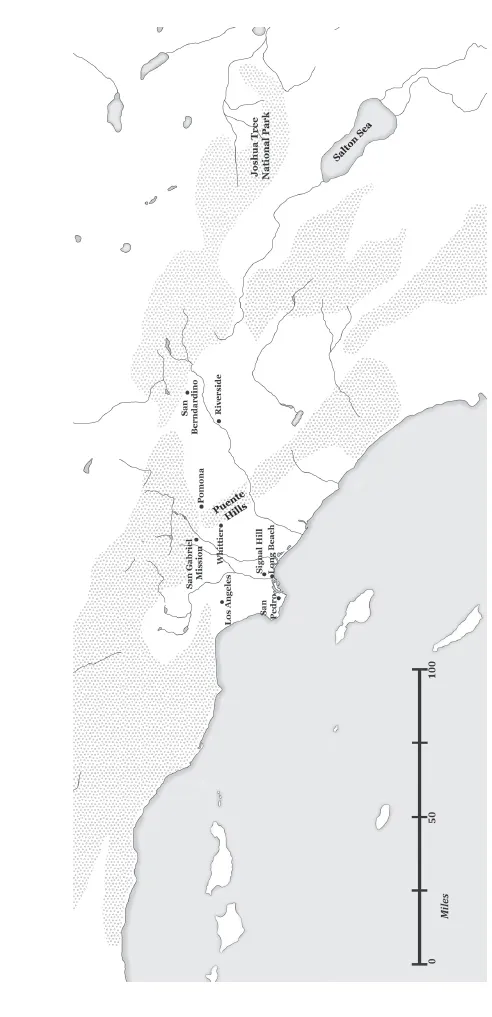

Figure 1.1 Major topographic features of Southern California

Plate tectonics has always played a role, and continues to do so, in the growth of Southern California as a region. About 25 million years ago, the westward-moving North American Continental Plate smashed into the eastward-moving Pacific Oceanic Plate. The denser oceanic plate subducted—i.e., slid underneath the less dense continental plate. Mountain building began as the continental landmass buckled; it is ongoing to the present day as the coastal ranges are thrust upward a fraction of an inch each year. Plate tectonics has also influenced the growth of vast strips of accreted terranes east of the Sierra Nevada; as the oceanic plate moved eastward, various pieces of oceanic crust, volcanic island arcs, seamounts, and fragments of small continents of different ages and origins became stuck to the oceanic plate at different times and places. When these immigrant rocks reached the western shores of the continent they were scraped off, one after another, and pasted like vast strips along its edge. The process resembles “groceries piling up at the end of a checkout-line conveyor belt” (Meldahl 2011:9). Complex systems of geological faults and, hence, earthquakes occur in zones where one accreted terrane butts into another. Heated magma from deep in the earth’s core rises in these cracks. This geothermal activity sometimes creates volcanoes (the Puente hills or the cinder cones in Joshua Tree, for example); sometimes hot springs such as Murrieta and others along the west-facing slopes of the San Jacinto mountains; and sometimes it creates bubbling mud pots like those at the south end of the Salton sea. Another noteworthy and important feature is that some strips of accreted terranes are more firmly glued to the continent than others. For example, about five to ten million years ago, the land west of the San Andreas fault broke off and began moving northwestward relative to the rest of the North American continent; it has moved 185 miles since the rupture was completed about six million years ago (Abbott 1999:169).

Climate change involves changes in temperature, the composition of the atmosphere, and precipitation as well as in the patterns of atmospheric and oceanic circulation. At one level, it reflects fluctuations in the intensity of solar radiation and small cyclical changes in the shape and inclination of the earth’s orbit and tilt as it wobbles around the sun. At a less remote level, the effects of climate change and plate tectonics interact in continually changing ways. Shifts in the patterns of oceanic and atmospheric circulation, for example, have local and regional effects as well as global ones. Increases or decreases in temperature affect evaporation rates. Where precipitation, runoff, and erosion do and do not occur is partly dependent on mountain building, the configuration of landmasses and oceans over the earth’s surface, and countless other effects of tectonic movement.

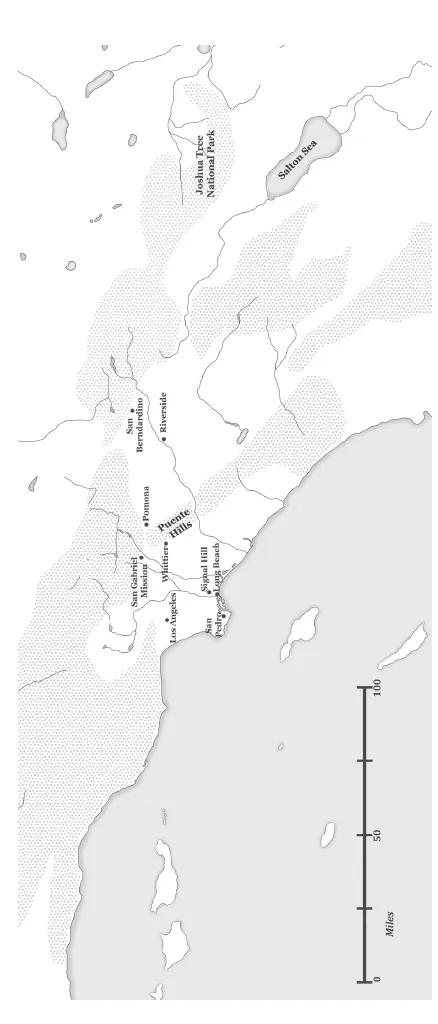

Figure 1.2 Location of places mentioned in the Preface and Chapter 1

The plant communities of Southern California have complex histories that reflect the westward expansion of the continental margin as well as changes in topography, temperature, and precipitation. Paleobotanist Daniel Axelrod (1977, figs. 5–5, 5–9) portrayed this history in terms of the proliferation and diversification of environmental zones during the past 50 million years. In his view, environmental zones whose plant communities were once relatively homogeneous in composition differentiated internally as new topographies, climates, local circumstances, and distinctions developed within and around them. The interplay of the climatic and geological processes combined with the evolutionary development of plant and animal communities to produce one of the world’s most diverse environments (e.g., Barbour et al. 2007). Moreover, the diversity of the large-scale habitats is further compounded by the fact that many microhabitats exist side by side in sheltered or freshly eroded places whose soils reflect the particularities of the underlying bedrock. Simply put, as time passed, the relatively flat coastal plain on the western edge of North America, which was never entirely homogenous in the first place, was transformed when the distinctions between coastal and inland areas became more pronounced, when mountains and highlands were uplifted, and when the mountains formed an increasingly effective meteorological barrier separating Southern California from lands to the east. These processes of change are still taking place in the Inland Empire and beyond. They still have real consequences for the inhabitants of the region.

Two brief examples illustrate the effects of these interactions. The first is the Los Angeles Basin. Two to four million years ago, it was a shallow inlet that stretched eastward almost to the Puente hills. The inlet slowly filled with sediments and organic material washed in by the San Gabriel and Los Angeles rivers. The land surface became Los Angeles, and the underlying organic materials were transformed by the weight of the sediments into the rich oil fields discovered in the basin in the early twentieth century. The second example is afforded by the unstable, south-facing slopes of the San Gabriel and San Bernardino mountains, which are home to chaparral and other plant communities as well as to scavengers and predators such as bears and mountain lions. After the Second World War, these unstable, fire-prone slopes were subdivided for residential construction. Two unacknowledged or unforeseen consequences of this building have been disastrous fires consuming large swaths of land and homes, and the concomitant destruction of natural habitats such that bears rummage through neighborhood garbage cans and coyotes stalk residents’ pets in search of food.

ADD PEOPLE AND STIR!

All people, from the most recent immigrant to the first groups to set foot in the region, are part of the environments of Southern California, have effected changes in them, and continue to do so. Enlightenment writers and other critics such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau, G. F. Hegel, and Karl Marx, were well aware that human beings were part of the natural world they inhabited. So were the Cahuilla, Gabrielino, and Luiseño peoples who lived in the Inland Empire long before the Spanish missions were established in the late eighteenth century. They knew that they were an integral part of the natural world they had helped to create and that their actions had potential and often unpredictable effects on that world (Bean 1972, 1978:582; Johnston 1962:41). They were and are much clearer about this metabolic relationship with the world they inhabit than many of the developers, boosters, and settlers who followed them to the region.

The Indian peoples who lived in the Inland Empire and its environs used a wide array of resource management practices. These included various harvesting technologies: pruning, coppicing, sowing, tilling, transplanting, weeding, and burning to encourage the growth of particularly important economic plants; they also burned grasslands to drive deer and other game (Anderson 2005:125–154; Aschmann 1959; Blackburn and Anderson 1993). As a result, the landscapes were already highly manicured when the Franciscan missionaries arrived. Descriptions by the first Spanish expeditions into the region paint especially vivid pictures of the management practices as well as the landscapes themselves. Fray Juan Crespí, who traveled with the Portolá expedition through Santa Ana and the San Gabriel Valley in July 1769, was struck by the fact that the grasslands had recently been burned by the local inhabitants (Stewart 2002:260). He also mentioned that the Indian people harvesting herbs on the edge of the San Elijo lagoon near Carlsbad in April 1770 complained because the expedition’s cattle were eating and trampling the plant foods in their fields. Participants in subsequent expeditions noted riparian forests of cottonwoods, sycamores, and oaks in the canyons and along the banks of the San Jacinto and Santa Ana rivers, and chaparral on the mountain slopes (Minnich 2008:33–40). Others who had journeyed through the Mojave desert in the 1770s saw saline springs surrounded by small grasslands as well as a river and a swamp “full of water” at the base of the north-facing slopes of the Transverse Ranges. A diarist on the first Anza expedition, struck by the paucity of pasture in the Salton trough, marveled at the lush flower-strewn prairie and pasture that stretched during the winter from the San Jacinto mountains westward across the treeless plain to the ocean. Hundreds of herds of antelope, ranging in size from about ten to fifty individuals, grazed in this vast pasture (Minnich 2008:33–40, 77).

The Spaniards brought livestock when they began establishing missions in Alta California during the 1770s; about a thousand cattle survived the journey. By the mid-1830s, the San Gabriel, San Luis Rey, and San Juan Capistrano missions had an estimated 56,000 to 255,000 cattle, 4,000 to 32,000 horses, and 44,000 to 155,000 sheep; the inhabitants of the Pueblo de Los Angeles had another 40,000 cattle and 5,000 horses. By all accounts, the animals were free ranging and intermingled in the pasturelands with antelope and other native grazers (Minnich 2008:82–89). This resulted in overgrazing in some localities and the encroachment of chaparral and trees into former pasturelands. The Spaniards also introduced a number of European annual grasses—most notably wild oat and mustard but also mallow, wheat, corn, filaree, and clover—that expanded quickly competing with the natural vegetation, especially in the moist, foggy areas along the coast. People living around the missions already viewed mallow as a weed or pest by 1800, and, two decades later, they described fields of mustard in San Diego and large stands of wild oat on the Puente hills (Minnich 2008:119–122). The picture was different in the interior from Rancho Cucamonga to the interior valleys south of Riverside; here the wild-flowers and invasive plants dried out during the hot summer months, except around the springs and areas with shallow water tables (Minnich 2008:147–149, 158). While wild oat and mustard dominated coastal pasture by 1900, wildflowers coexisted with filaree and clover in the interior. This was a new kind of pasture. While the composition of the coastal and inland pastures of Southern California were similar in the 1770s, they became increasingly distinct in the nineteenth century because of invasive plant species. The inland pastures of Riverside and San Bernardino were further transformed from the 1890s onward as wild oat and mustard became the dominant plants by the 1920s. Similar changes were also taking place in the deserts, where another invasive plant, split grass, was in the process of becoming the dominant annual by the 1940s (Minnich 2008:186, 222).

The appearance of these “second-wave invasive plants” was not the only source of the changes taking place in Inland Empire landscapes in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The missions and the pueblo of Los Angeles had gardens that included citrus and fig trees, grapes, olives, wheat and other grains, and some vegetables. They essentially extended Mexican and Mediterranean crops and agricultural practices to Southern California. The Southern California economy was based largely on herding in the first half of the nineteenth century; in 1871, there were only ninety thousand acres (roughly 140 square miles) of agricultural land in the entire state. The transformation of the grazing landscape in Southern California in the latter half of the century began with two colonies. The first was the Mormon colony established in San Bernardino in 1851, which purchased thirty-five thousand acres from a local ranchero. About 10 percent of the land was planted in grains; the fields were irrigated by gravity-flow canals that brought water from Lytle creek and two other streams draining the south-facing slopes of the San Bernardino mountains. The second was the Anaheim colony, founded by a group of German settlers who had failed make their fortunes in the gold fields and turned their efforts instead to commercial viticulture. By 1861 they were producing seventy-five thousand gallons of wine a year. The sheep ranches in Riverside suffered greatly during the prolonged drought of the 1860s. By the end of the decade they were giving way to cultivation, as the founders of the Southern California Colony Association completed gravity-flow irrigation canals to bring water from the Santa Ana river to arable land on the east bank (Raup 1959). While an earlier project to grow silkworms commercially failed, the completion of the Gage canal a decade and a half later brought water from an artesian spring to fifteen thousand acres of arable land south of the colony. This and similar ventures in other parts of the Inland Empire sparked a real estate boom in the 1870s and 1880s and transformed the regional economy from one based on cattle ranching to one based on citrus farming (Patterson 1996). During this period immigrants, largely from the Midwest, established other agricultural colonies from Pasadena to Redlands (Dumke 1944). By 1900 more than 832 thousand acres of land were under cultivation in Los Angeles, Riverside, and San Bernardino counties—that is, roughly 7 percent of agricultural land in the state. In less than thirty years the region had become a major agricultural producer, and the shift from ranching and extensive grain agriculture to intensive specialty crops such as citrus was well under way.

The expansion of agricultural landscapes in the late nineteenth century was part of a much larger set of interconnected events that included the virtually simultaneous development of railroads, seaports, water systems, immigration, new towns, increasingly national markets for agricultural produce, and boosters who created and successfully spread the idea of the “California dream.” This complex is worth an additional look, in order to see how the processes intertwined to produce the artificial landscapes that now cover much of Southern California.

The only railroad in Southern California in 1870 brought passengers and goods from the fledgling seaport of San Pedro to Los Angeles, a distance of thirty-six miles. At the time, the U.S. Census reported that twenty-two thousand people resided in Los Angeles and San Bernardino counties (Orange and Riverside counties would not become recognized political units until 1889 and 1892–1893, respectively). By 1890 three railroad companies—the Southern Pacific, the Union Pacific, and the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe—had built rail routes that crisscrossed Southern California. They connected the Inland Empire and Los Angeles County not only with San Francisco, Barstow, and San Diego but also with Yuma, Salt Lake City, New Orleans, Chicago, and points further east (Robertson 1998).

In 1882, entrepreneur George Chaffey organized two model agricultural colonies, Etiwanda and Ontario. These ventures created an additional ten thousand acres of arable land in the Inland Empire. What distinguished Chaffey’s agricultural colonies from earlier ones was that he sold water rights as well as land: the new owners had shares in his San Antonio Water Company. The company, and others modeled after it, also generated hydroelectric power as a by-product. Between 1900 and 1905 Chaffey and his associates also sold land and water rights to ten thousand recent settlers, who farmed about 150 thousand acres in the Salton Trough (the Imperial Valley). Water for the crops came via a gravity-flow irrigation system from the Colorado River. Unfortunately the river changed channels in 1905, pouring billions of gallons into the trough over the next two years and creating a vast inland lake (the Salton sea) in the process.1 Some of the land brought under cultivation has been underwater for the past century (Starr 1990:15–30). In the early 1900s Chaffey brought his innovation to other parts of Southern California, purchasing a part interest in the East Whittier and La Habra Water Company and starting another colony and water company in Indian Wells, south of the Owens Valley.

These and other efforts not only increased the amount of land under cultivation but also attracted new residents as well. There was a thirtyfold population increase in the region in the forty years between 1870 and 1910; the rates of population growth in subsequent decades to the present have paled by comparison, even though there have been enormous increases in the number of individuals who were either born in Southern California or immigrated to the region.

Southern California boosters—publicists like Charles Lummis and L. M. Holt, most notably—created a series of images of Southern California in promotional brochures, distributed in the Midwest and the East, that were designed to attract both visitors and potential settlers. They simultaneously portrayed the area as a natural paradise with a healthy climate, a land of wealth and prosperity with thousands of small farms, and a place where built landscapes replaced natural ones; it was a land of progress and opportunity with a utopian future and a suburban lifestyle that lacked all of the dangers posed by crowded industrial cities and the teeming masses of foreign workers who inhabited them (McLung 2000). The railroads, especially the Southern Pacific, promoted this “Garden of Eden” imagery from the early 1870s onward. They hired writers to present the attractions of California for audiences across the country; they facilitated tourism by offering reduced fares and special passenger cars for land seekers from the Midwest, especially during the winter months when wildflowers still covered the hills; they sponsored exhibitions at world’s fairs; and they published magazines such as Sunset that described tourist attractions like Yosemite National Park. Lavish hotels were built in Coronado, Santa Monica, and Carmel, and health resorts appeared at many of the desert hot springs. Local officials also organized special events, such as the annual Rose Parade in Pasadena, to refine the message and to promote the region even further (e.g., Orsi 2005:130–167...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of Illustrations

- 1 Living Landscapes

- 2 The First Nations

- 3 The Spanish Colonial Economy in Southern California

- 4 Southern California in the Wake of Mexico’s War of Independence, 1822–1848

- 5 The American Empire and Southern California, 1836 to early 1870s

- 6 Land, Railroads, and the Rise of the Orange Empire, 1860–1930

- 7 A Regional Perspective on the Orange Empire and Its Neighbors, 1875–1945

- 8 War, Real Estate, and the Rise of the Inland Empire, 1940–1978

- 9 From Inland Empire to Warehouse Empire, 1980–2014

- 10 Toward the Historical Political Economy of a Region

- Epilogue

- References

- Index

- About the Author