- 170 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

US foreign policy in the Middle East has for the most part been shaped by the eruption of major crises that have revealed the deficiency in and bankruptcy of existing consensus and conceptions. Crises generate a new set of ideas to address the roots of the crisis and construct a new reality that would best serve US interests. Further, crises stimulate new ideological and ideational debates that de-legitimate existing practices and prevailing ideas. Yakub Halabi analyzes the way ideas and conceptions have guided US foreign policy in the Middle East, the erection of institutions through which these ideas were brought into practice, and the manner in which these ideas became obsolete and were modified by new ideas. The selection of crises examined is persuasive and provides a critical lens to observe important turning points in American foreign policy.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access US Foreign Policy in the Middle East by Yakub Halabi in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

International crisis has long been a crucible for the development of US policies. Among the Middle Eastern crises that have erupted into American public awareness since World War II are the Arab-Israeli war of 1948, the Iran crisis (1951–53), Suez (1956), Lebanon (1958), the June or Six-Day War (1967), the War of Attrition (1969–70), the October or Yom Kippur War and the oil embargo (1973–74), the Iranian Revolution (1979), the Iran-Iraq War (1980–88), the First Iraq War (1990–91), 9/11 (2001), and the Second Iraq War (2003–present). These crises commonly expose deficiencies in the pre-crisis US policy toward the region and resulted in changes to that policy.

Following each of these crises, the US grappled with the fundamental problem of how to create a stable post-crisis order that would both serve its own interests and uproot the sources of the crisis. These junctures constituted dramatic moments of turmoil that rendered the pre-crisis order obsolete and forced policy to change.

The Middle East in general has remained a main centre of concern for the US because of the West’s dependency of the region’s oil resources. The aim of this book is to understand change and to explain the vicissitudes in US foreign policy toward the Middle East. When does change take place? What factors or variables cause a state to ditch its previous policy and to embark upon a new course? What type of crises affects change? What is the role of ideas in shaping new policies?

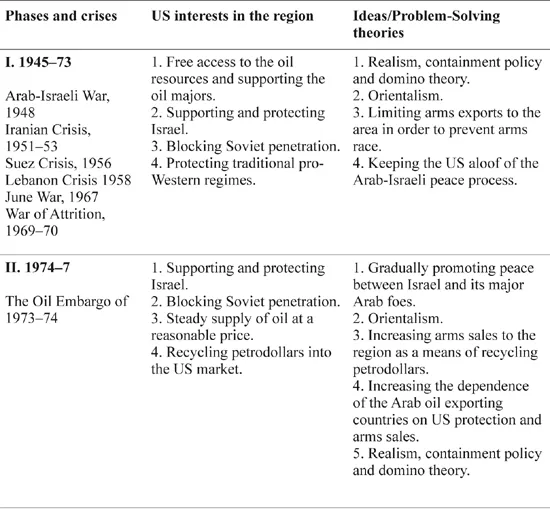

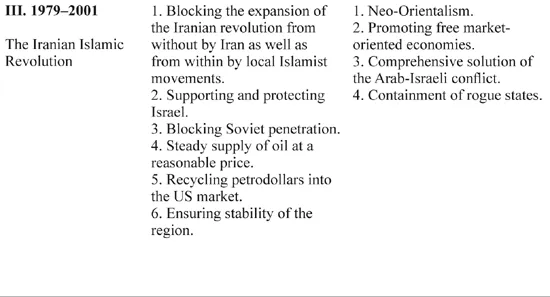

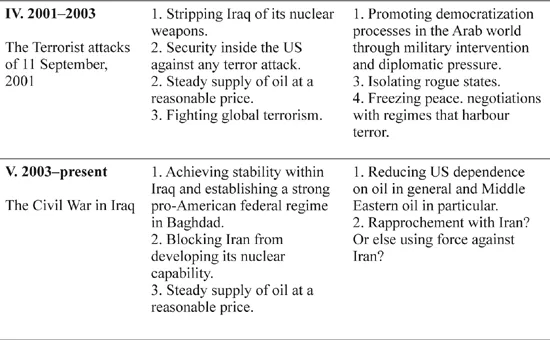

The period after World War II saw an intensive and extensive expansion of US military and diplomatic involvement in the Middle East. The United States was historically disconnected from the abuses of colonial policy in the area (Dobson and Marsh 2001; Quandt 1970). Many Arab conservative leaders therefore welcomed US involvement at the regional level. Yet US foreign policy toward the Middle East since World War II has been neither coherent nor consistent, especially during the first phase (1945–73) (see Table 1.1), given the discrepancy between various American interests and the complexity of realizing these interests. This inconsistency was highlighted by the crises, whose eruption magnified the uncertainty surrounding the realization of US interests and required a great deal of creativity by American experts on the Middle East (Terry 2005).

In general, US policy in the Middle East cannot be analyzed on a purely rational basis. This theory presumes that policymakers possess full information about the event under consideration and they always choose the policy option that maximizes their utilities. It also explicitly assumes that foreign policy is always in flux and that policymakers persistently re-examine their policies and do not hesitate to ditch a policy that does not maximize their utilities, or that they are always ready to adopt a new policy line that could bring about better results. States unfortunately do not operate in this manner in the domain of foreign affairs, as states do not re-examine their policies every day.

Table 1.1 American foreign policy in the Middle East: crises, interests and ideas

Based on the writings of scholars who have examined the impact of ideas on state behaviour (Adler and Haas 1992; Goldstein 1995; Goldstein and Keohane 1993a; Haas 1992; Keohane 2000), this book argues that reality in the Middle East is not causally independent of the minds of policymakers. Crises create uncertainty and spur policymakers to come out with new ideas as solutions that may deliver better results. The US foreign policy toward the Middle East from World War II to the Second Iraq War has experienced the challenge of responding to major crises in the region, shaping long-term policy that directed different administrations, aimed at stabilizing the Middle East. The argument of this book is that each one of the major crises menaced US interests and highlighted the shortcomings in existing policies, thus undermining existing policies’ validity in the eyes of top American policymakers. This uncertainty stimulated the consolidation of a new set of ideas among these policymakers, marking a departure from previous beliefs and aiming to address the roots of the recent crisis and to construct a new reality that would better serve US interests. In this sense each set of ideas became embedded within formal US institutions, influencing the way American policymakers contemplated and comprehended foreign policy, assessed problems, and formulated strategies toward the region. Such embedded ideas, in turn, regulated American relations with the Middle East—a political region in which power and interests shape outcomes by the virtue of the ideas that channel them. In short, the eruption of a major crisis reset the prevailing mindset and allowed the emergence of another mindset. Each set of ideas endured till the eruption of the next major crisis. In other words, US foreign policy in the Middle East shows a remarkable continuity between major crises.

Finally, ideas have a double function. First, ideas shape long term strategies, thus guide US foreign policy. Second, ideas create understanding with regional forces about the desired order, resulting in the consolidation of a hegemonic or more precisely semi-hegemonic order in the Gramscian sense. This point is explained in more detail in the next chapter.

Shared ideas are not, however, consolidated in an ontological vacuum. Indeed collective ideas obviously guide foreign policy. Yet such ideas have a constitutive power in the context of other fundamental forces that facilitate such guidance. Power facilitates change and makes its occurrence probable, while it is the power of shared ideas that bring about change and make it practical. Metaphorically, we may think of the forces of gravity and friction as ones that not only constrain our movements, but also facilitate it. Yet the direction of our movement is guided by our mind—ideas. The question that remained unanswered is what affects change in shared ideas, and why certain crises alter shared ideas or policy lines, while other crises do not.

From the list of crises mentioned above, it is possible to discern four major ones that constituted turning points in US foreign policy in the Middle East: the oil embargo of 1973–74, the Iranian revolution, the events of 9/11, and the Second Iraq War. Each one of these crises had a profound impact on US economy, society, or polity and raised American public awareness about US policy toward the region (see Table 1.1).1

Phase one, between 1945 and 1973, marks the first epoch of shaping and defining US policy interests in, and consolidating American understanding of, the political culture of the Middle East. Regional crises that influenced forged and then altered US Middle Eastern policy were the Iranian crisis of 1951–53, the Suez crisis of 1956, the Lebanon crisis of 1958, the Six-Day War, and the War of Attrition. These crises had limited domestic impact within the US. They brought about a learning process but did not result in redefinition of US interests or rethinking the efficacy of its current policy. For instance, the Iranian crisis of 1951–53 and the Suez crisis gave rise to the desire to isolate nationalist leaders. These two crises nonetheless marked neither a watershed in the American comprehension of the politics of the region nor a redefinition of American interests in the area.

Phase two, between 1974 and 1979, started with the Arab oil embargo of 1973–74, the sharp rise in oil prices, high inflation, and economic recession. The embargo, nationalization of oil resources, and the accumulation of petrodollars in the hands of few sparsely populated oil monarchies added more complexity to the US policy and required a re-examination of the current policy.

The Islamic revolution in Iran and the captivity of American diplomats as hostages marked the onset of phase three (1979–2001). The revolution cost the US its control of Iran and showed the rise of anti-Americanism among Muslim societies, and also brought about another sharp rise in oil prices. This event undermined the state-centric approach that ignored Arab/Muslim societies and discredited the ideas of orientalism that called for Western cooperation with authoritarian traditional regimes, with minor embroilments in domestic affairs. The crisis stimulated a new thinking, especially about American cooperation with corrupt, authoritarian Middle Eastern regimes that left the lower classes alienated (Sadowski 1993).

The terrorist attacks of 11 September, 2001, marked the advent of the fourth phase. These events undermined the feeling of security within the US and raised once again questions about US cooperation with authoritarian regimes and the lack of democratization in the region. These events brought about a major reassessment of US foreign policy and redefinition of US interests in the region (Miller and Stefanova 2007, 18; Pauly 2005, 41).

And finally, the sectarian war in Iraq that followed the US invasion in 2003 has caused a rethinking of the US’s democratization policy in the area and marks the onset of a new phase. At this stage it is still too early to assess new directions in US foreign policy toward the Middle East, but it is possible to assert predict with some certainty that future American administrations may refrain from promoting democratization processes in the Arab world through military or even peaceful means (Pillar 2001, 14; Pauly and Lansford 2005, 31). Future administrations may also seek to diminish US dependency on Middle Eastern oil supplies in the face of the environmental damage caused by the use of fossil fuel, while some may consider that the costs of US involvement in the region outweigh the benefits.

Over the past few decades, major crises have impelled a reassessment of US foreign policy toward the Middle East and spurred the rise of new ideas on how to cope with the post-crisis reality. While each major crisis undermined the credibility of the set of ideas that underpinned pre-existing policy, the crisis allowed the incumbent president to contemplate new ideas that would reshape US policy or construct new institutions aimed at maintaining political stability in the region.

In general, US foreign policy toward the Middle East has oscillated between two positions that are not mutually exclusive. The first is a global approach: the US presumes that overall stable relationships between states would result in stability within each pro-West Middle Eastern state and consequently regional stability. The US pursued a state-centric policy, with minor interference in the internal affairs of the Middle Eastern states. The US adopted this policy until 1979. Until 1974, the US sought to maintain regional stability by limiting arms sales (hoping that this would mitigate the arms race between the Middle Eastern states), blocking Soviet penetration into the area, and focusing merely on serving American interests. Between 1974 and 1979, the US hoped to realize regional stability through a peaceful solution to the Arab-Israeli conflict. In the aftermath of the oil embargo of 1973, Western dependence on Middle Eastern oil increased (Gilbar 1997a, 33), while the oil monarchies were the main pillars of the American-led order in the region. The Arab oil exporting countries and Iran had nationalized the oil companies throughout the 1970s and became responsible for downstream as well as upstream processes of oil supply (Sampson 1975). These regimes had also accumulated great sums of petrodollars. Consequently, the United States needed to create a common understanding with these regimes about a reasonable price of oil and to put in place institutions and policies that would recycle petrodollars into the US market.

The second position began immediately after the Iranian revolution and called for deepening US intervention in the internal affairs of the regional states, while the aggregation of stability in each of these states would result in a regional overall stability. By pursuing this policy, the US aimed to assuage or even restructure what is perceived by many American policymakers as irrational trends typical to the Arab-Islamic culture in its anti-modern and anti-Western behaviour. The Iranian Revolution severely challenged the American perception regarding the everlasting passivity of Arab societies and their deference to traditional leaders. In response, the US sought to construct new institutions that would address the problems of alienated societies in order to preempt the spread of the Islamic revolution throughout the Arab world. During this time, the US constructed capitalist institutions that would raise the average living standards of the lower classes, yet stopped short of advocating democracy. The United States also needed to keep Iran from exporting the revolution into neighbouring Arab countries. This new reality required new thinking. The solutions were not obvious to US policymakers.

The terrorist attacks of 11 September, 2001, deepened US interference in the internal affairs of the Middle Eastern states. For the first time, the US began aggressively promoting the democratization of Islamic polities. This process was predicated on abandoning ideas regarding the incompatibility of Islamic values with democracy, and further underpinned by the conviction that ordinary Muslims, who live in free societies would be reluctant to join terrorist organizations, such as al-Qaeda or perceive the US as a foe.

In short, during the last three and a half decades, US foreign policy toward the Middle East has shifted from advocating authoritarianism, to embracing capitalism, and finally, to promoting democratization. These shifts have been administered after new ideas emerged to supersede old ones, thus justifying new thrusts in the policy approach.

Two genres of theoretical approaches offer explanation for American foreign policy in the region: ‘structural’ and ‘cultural’. Within the structural approach, we encounter two major theories: neo-realism/ hegemonic stability and interdependence.

The classical conception of international relations is that under the conditions of anarchy in the international system, crises erupt and wars occur because there is no supranational organization that is able to regulate relations between sovereign states. Foreign policy is conducted in an arena of power politics, where there is no reliable mechanism for coordinating relations and regulating disputes. Under these conditions, power is the most efficacious instrument in conducting foreign policy, where in the words of Thucydides ‘the strong do what they can, and the weak suffer what they must.’ (Thucydides 1998, Book V, verse 89). In this regard, the hegemonic stability theory examines the international distribution of power that acts as a determinant for a state’s role (Lake 1995; Keohane 1996). Being the most powerful state in the world since World War II, the US has become a hegemon in both the West and Middle East, whose role has concentrated on providing international public goods, including a steady supply of oil. In fulfilment of this purpose, the US has had to participate in the regional balance of power throughout the Middle East in order to keep regional or state aspirations from controlling the oil fields, for example, as Egypt under Nasser (Pan-Arabism) or Iraq under Saddam Hussein. Furthermore, historically, military power was an efficacious instrument for generating wealth, while wealth was always subordinated to power. In the Middle East, controlling the regional oil fields, directly or indirectly, has been a source of power.

The theory of interdependence, while not dismissing the classical axioms of power politics, nonetheless, urges attention to a set of new forces in international politics that engendered interdependency between states. In our present era there are many states, especially in the Middle East region, that are impoverished but command tremendous military power, while others are wealthy, yet militarily weak. The fact that some states are militarily weak does not render them less influential or an easy prey to the more powerful ones. In the US, the economy has become sensitive to fluctuations in world commodity and financial markets, and vulnerable to energy crises. For many years economists were confident that national governments can control inflation and unemployment by relying on fiscal and monetary tools. The oil crises in 1973–74, for instance, had proved that small states could exploit their power within an issue area (the oil market) and inflict tremendous costs on the hegemon, while national remedies are unlikely to succeed without coordination of policies with other nations. The theory of interdependence examines asymmetrical distribution of power within an issue area (Keohane and Nye 1989). The seminal analysis made by Keohane and Nye shows how small states, despite their overall power inferiority relative to a superpower, can influence outcome in a specific issue area and even create issue linkage, thus influencing international politics in areas that are beyond their control. In these circumstances, military power does not seem to reap benefits commensurate with its costs, nor a useful tool to deal with world economic crises.

By contrast, the cultural approach looks at the Arab-Islamic culture as an ontological, fixed structure that controls the lives of Arab-Muslims. So called ‘orientalist’ scholars insist that the US should work in unity with these cultural forces—that is to say, they prescribe cooperation with traditional authoritarian regimes in the Middle East (Kedourie 1994; for a critique of this approach see Hudson 1995; Hudson 1996; Anderson 1995).

This book argues that neither approach captures the dynamics of US foreign policy in the Middle East, since both are unable to explain long-term transformation from what Gramsci calls one historical block into another. The realist theory refers to power as the most significant variable influencing outcome in international relations. Yet power does not determine ideas, nor shape the way states think of each other, nor automatically lead to a conflict between states. The interdependence theory describes the way states react to power relations within an issue area, yet without taking into account how the process of interaction reshapes the identity of the involved actors. The theory cannot explain, for instance, how culture shaped the interaction between the US and its Middle Eastern counterparts or how interactions shape what Alexander Wendt calls the common identity of these actors (Wendt 1999). Likewise, the hegemonic stability theory examines the distribution of power that ascribes an international role to the hegemon—an influence which, in turn, is translated into state policy (Lake 1995; Gilpin and Gilpin 2001). In this view, the hegemon ensures international public goods and punishes recalcitrant actors, but the theory assumes that the hegemon stops short of attempting to influence their identity.

The cultural orientalist approach, by contrast, assumes that the hegemon takes the identity of the Arab states as exogenously given, rather than one that is (at least partially) shaped by the hegemon itself. Furthermore, both the structural as well as the cultural approaches do not provide for a learning process on the part of the hegemon, especially after the eruption of a crisis. At an early stage of a crisis, the sources of the crisis are analyzed and new ideas emerge—ideas that channel the hegemon toward its mission of forging the identity of Middle Eastern countries. It is my argument, therefore, that none of these approaches examines the arrangements through which ideas are filtered out under the given international, material constraints, and which are then incorporate...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Tables

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Ideas Matter

- 3 Consolidation and Learning by Doing: US Foreign Policy in the Middle East, 1945–1973

- 4 The Oil Embargo Crisis in 1973–1974

- 5 The Iranian Revolution and US Foreign Policy in the Middle East Between 1979–2001

- 6 September 11 and the War on Terror: The Rise of Neo-Conservativism

- 7 Back to the Future: The Second Iraq War and the United States Democratization Policy in the Middle East

- 8 Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index