- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

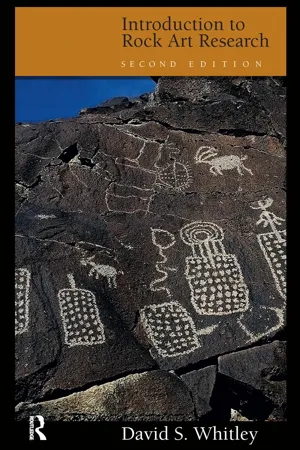

Introduction to Rock Art Research

About this book

First published in 2005, this brief introduction to methods of studying rock art has become the standard text for courses on this topic. It was also selected as a Choice Magazine Outstanding Academic Book in 2005. Internationally-known rock art researcher David Whitley takes the reader through the various processes needed to document, interpret, and preserve this fragile category of artifact. Using examples from around the globe, he offers a comprehensive guide to rock art studies of value to archaeologists and art historians, their students, and rock art aficionados. The second edition of this classic work has additional material on mapping sites, ethnographic analogy, neuropsychological models, and Native American consultation.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Introduction to Rock Art Research by David Whitley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

Rock art is an archaeological phenomenon found in many regions of the world. Despite this fact, and for a complicated series of historical reasons, it has long been ignored by most Anglophone archaeologists, whether working in the Americas, Africa, Europe, or Australia (e.g., see Whitley and Clottes 2005). The status of rock art research has started to change, however, with recent studies showing its importance in reconstructing symbolic and religious systems (e.g., Boyd 2003; Bradley 1997; Garlake 1995; Keyser and Klassen 2001; Layton 1992; Lewis-Williams 1981, 2002; Lewis-Williams and Dowson 1989; Lewis-Williams and Pearce 2004; Rajnovich 1994; Rozwadowski 2004), defining gender relations in societies (e.g., Hays-Gilpin 2004, 2005, 2006; Sundstrom 2008; Zubieta 2006, 2009), identifying cultural boundaries (e.g., Francis and Loendorf 2002) and cultural change (e.g., David 2002; Whitley et al. 2007), and studying the origins of art and belief (e.g., Clottes 2003; Clottes and Lewis-Williams 1998; Lewis-Williams 2003, 2010; Whitley 2009)—among other topics.

Rock art sites are also highly valued by indigenous peoples, who generally view them both as sacred and as important components of their cultural patrimony (e.g., see Utemara with Vinnicombe 1992). The art has captivating aesthetic qualities, causing it to be highly regarded—and exploited—by the general public in ways that the dirt archaeological record cannot match (indeed, rock art T-shirts are as common today as rock band T-shirts). Rock art sites may be attractive for cultural tourism and thus contribute to the economic health of a community or region. All of these are reasons for studying, managing, and preserving rock art, although its inherent fragility sometimes makes this a difficult task.

This book presents an introduction for archaeologists, cultural resource managers, and students interested in studying, managing, and preserving rock art and rock art sites. Such a book is necessary because, even while rock art research is a subdiscipline within archaeology (e.g., see Morwood 2002), it requires different techniques, addresses slightly different analytical problems, and has its own specialized body of literature. Moreover, American archaeology students do not usually receive any formal training in rock art research. My purpose in this short book is to provide a bridge into rock art research and its literature in order to encourage the study and preservation of this important aspect of the archaeological record.

This chapter introduces some basic definitions and takes a brief look at rock art production techniques. (For a more detailed analysis of rock art techniques, see GRAPP 1993.) Chapter 2 presents an introduction to rock art fieldwork, which differs in important ways from the standard archaeological techniques used in excavation and regional surveying.

Chapter 3 addresses the important analytical problem of classification. This problem, as you will see, has vexed rock art research for the last century, yet it is always the starting point for analysis. Classification is followed in Chapter 4 by a discussion of approaches to dating. Chronology has been a difficult issue for rock art researchers. While chronometric rock art techniques still require much basic research, there is nonetheless cause for substantial optimism about our ability to date rock art.

A series of related chapters then sets forth the topic of rock art interpretation. My premise in writing these chapters—as in conducting my own rock art research—is that our interpretations must adhere to scientific method, whether we are concerned with reconstructing a symbolic system in its own terms or with explaining the part a symbolic system may play in adaptation to the environment. Chapter 5 thus begins with a brief description of scientific method (that is, an approach to selecting a preferred hypothesis from a series of competitors) before considering rock art interpretations in terms of two broad categories, as suggested by Taçon and Chippindale (1998): informed and formal methods.

Informed methods, outlined in Chapter 6, emphasize ethnography and symbolic analysis, and thus aim to provide an insider’s understanding of the art—that is, an interpretation identical or similar to that of the art’s creator. Formal methods, in contrast, concern outsiders’ perspectives. These are considered in two sections: Chapter 7 describes neuropsychological analyses, whereas Chapter 8 considers quantitative, landscape, archaeoastronomical, and other approaches to rock art interpretation. Chapter 9 turns to site management and conservation, a topic important to all who study rock art. I conclude this book with some brief comments on the future of rock art research.

DEFINING ROCK ART

Rock art is landscape art (Whitley 1998b). It consists of pictures, motifs, and designs placed on natural surfaces, such as cliff and boulder faces, cave walls and ceilings, and the ground surface. Rock art is also sometimes referred to as cave art or parietal (wall) art. Regardless of designation, the defining characteristic of rock art is its placement on natural rock surfaces, thereby distinguishing it from murals on constructed walls, paintings or carvings on canvas, wood, ceramics, or other surfaces, and freestanding sculptures.

Rock art includes pictographs (paintings and drawings), petroglyphs (engravings and carvings), and earth figures (intaglios, geoglyphs, or earthforms). Some researchers also include pecked pits and grooves, sometimes called cup-and-ring petroglyphs or cupules, as another form of rock art. Pictographs and petroglyphs are found on rock art panels. These are approximately flat surfaces that are the fracture or weathering planes of a natural rock outcrop.

Although there are exceptions, most rock art made by traditional, non-Western cultures was created during rituals of some kind. For this reason, rock art research is a kind of archaeology of religion (Lewis-Williams 1995; Whitley 2001, 2008a; see Steadman 2009). Some researchers object to the inclusion of the term art in “rock art,” implicitly or explicitly arguing that the Western concept of art is not appropriate for traditional, non-Western cultures. They hold that the use of the term rock art is an essentialist projection on the past, a way of applying our own contemporary cultural conceptions inappropriately to others. They suggest, as alternatives, terms like rock graphics or the hyphenated rock-art. I prefer the old, unhyphenated term rock art for a variety of reasons, not least of which is my interest in continuing reasonable and long-standing archaeological traditions. As an archaeologist, my concern is with preserving the past. This necessarily includes archaeological traditions, unless they are convincingly shown to be pernicious or simply wrong.

More important, it is clear both that our Western artistic tradition includes the kinds of performative and religious art found in rock art created by non-Western, traditional cultures, and that these same non-Western cultures are capable of appreciating the aesthetic qualities that are (for some) the hallmarks of Western art. As Sven Ouzman (2003) has sagely observed, the argument that the term rock art is somehow inappropriate for traditional non-Western cultures necessarily implies that “we” create “art,” whereas traditional cultures create something else—and something less. This seems unreasonable. Accordingly, I use this term without apology throughout this book.

PICTOGRAPHS

Pictographs are paintings or drawings made, worldwide, with common mineral earths and other natural compounds. Red, a frequently used color, typically is made from ground ocher; black is usually made from charcoal, but sometimes from other minerals (e.g., manganese); white is from natural chalk, kaolinite clay, or diatomaceous earth. Other, rarer, colors are also made from naturally occurring mineral or plant sources.

Regardless of source, the pigments are usually ground and then mixed with a liquid, such as water, animal blood, urine, or egg yolk, and applied as a kind of wet paint (Fig. 1-1). Or, they may be dry-applied as a kind of “chalk” or pencil (Fig. 1-2). A simple piece of charcoal, for example, works very well for drawing on a rock surface.

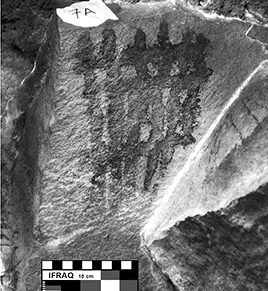

Pictographs can thus be divided into wet-applied paintings and dry-applied drawings. Wet-applied paints are continuous, even over a rough rock surface; dry-applied drawings often show concentrations of pigment on high spots on the rock face. Drawn lines thus may be discontinuous when examined with a hand lens.

Figure 1-1a Pictograph created with wet paint. This example, a grid, is from the “Antilope Well” site in Lava Beds National Monument, California. It was made with a highly liquid black paint (probably charcoal and water), and runs of paint can be seen along the line margins.

Figure 1-1b Most wet paint is more viscous, causing it to pool or puddle across minor rock-surface irregularities. This painting, of a Pacific pond turtle, is typical. It is from Saucito Ranch, Carrizo Plain National Monument, California, and is painted in red, white, and blue-black.

Figure 1-2 Geometric pictographs drawn with dry black pigment, probably a piece of charcoal. Note the natural hole or vesicle in the center of the basalt panel; charcoal has been rubbed on the panel, creating a “blur,” at center left. Symbol Bridge site, Lava Beds National Monument, California.

Wet-painted pictographs may be placed on a rock surface using a brush, the fingers, or a stamp. Brushes were usually made from the tip of the tail of a small animal, or from shredded and bound plant material (e.g., agave fiber). It is relatively easy to tell whether paint was applied with a brush or with the fingers, based on the thickness and consistency of the lines. Finger-painted motifs are “cruder.”Finger-dots are particularly common in some areas (Fig. 1-3). Sometimes these dots are arranged into motif patterns. At the famous site of Lascaux, a kind of stamp was employed in some cases to apply pigment; it was probably made of fur or plant material (Aujoulat 2004; Geneste et al. 2004).

Figure 1-3 Black finger-dots arranged into a geometric pattern, along with rectilinear geometric motifs finger-painted onto the panel. Symbol Bridge site, Lava Beds National Monument, California.

Two special categories of pictographs also exist. One of these is handprints (Fig. 1-4). These may not be universal to all rock art-producing cultures, but they are quite common in the Americas, in southern Africa, in Australia, and in Western Europe. There are three kinds of handprints. Standard handprints involved coating the hand with wet paint and then pressing the hand against the rock surface. Alternatively, a design (e.g., a spiral) could be drawn on the coated hand before pressing it against the rock, creating a handprint with an internal pattern.

The third kind of handprint involves an entirely different approach to painting. This uses dry pigment blown onto a rock surface through a tube—a kind of airbrush or spray-painting. For handprints, this involves placing the hand on the rock surface and then blowing the paint onto it. The result is a negative print of the hand in outline, usefully referred to as a...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Tables

- Preface to the Second Edition

- Preface to the First Edition

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Rock Art Fieldwork

- Chapter 3: Classification

- Chapter 4: Rock Art Dating

- Chapter 5: Scientific Method and Rock Art Analysis

- Chapter 6: Symbolic and Ethnographic Interpretation

- Chapter 7: Neuropsychology and Rock Art

- Chapter 8: Other Formal Approaches

- Chapter 9: Management and Conservation

- Chapter 10: Archaeology, Anthropology, and Rock Art

- Appendix: Rock Art Recording Forms

- Glossary

- References

- Index

- About the Author