eBook - ePub

Foreign Direct Investment

Smart Approaches to Differentiation and Engagement

- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

As the world continues to recover from one of the most dramatic financial crises in a generation, expanding corporations are increasingly, yet cautiously, seeking out international investment opportunities. At the heart of this fragile investment recovery lie trust and confidence. With an unprecedented number of investment promotion agencies and economic development organisations now competing for the attention and business of a more cautious and discerning investor audience, smart approaches to strategic differentiation, communication, engagement and investment services are becoming increasingly critical if these agencies and organisations are to succeed. At the same time, transparent and responsible approaches to investment, coupled with effective, compelling advocacy, are increasingly important to the success of companies' investment projects. Daniel Nicholls' Foreign Direct Investment offers an exploration of some of the key trends, issues and practices that are shaping the global FDI landscape. Along the way he provides insight into how economic developers and investors alike can make the most of their opportunities and mitigate reputational and communications challenges that can impede or hinder a successful investment. By presenting perspectives and priorities from both sides, Daniel Nicholls' book bridges the 'investment gap' by giving its readers an important insight into what matters to the other side. This book represents a smart investment for anyone involved.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Foreign Direct Investment by Daniel Nicholls in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 FDI in a Downturn: Trends and Lessons Learned

What we clearly need are new models for global, regional, national and business decision-making which truly reflect that the context for decision-making has been altered – in unprecedented ways.

Klaus Schwab

The keystone for all foreign direct investment is confidence, and the bedrock of confidence is stability. Ever since the 2007 subprime mortgage crisis heralded the onslaught of the worst global financial meltdown since the Great Depression, we have been living in a far more questioning – and far less confident – world.

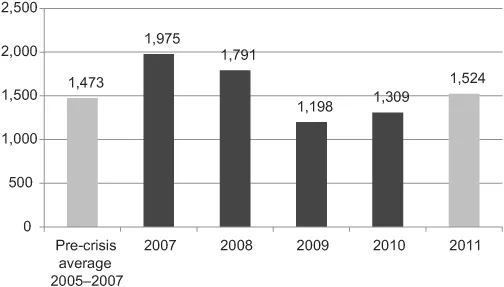

It therefore came as no surprise that levels of global FDI activity declined in 2009 compared with 2007 and 2008.1 FDI inflows saw a progressive decline from an all-time high of US$1.97 trillion in 2007 to just under US$1.2 trillion in 2009, based on figures from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD).2 Since 2009, seen by many as having been the height of the crisis, there have been increasing signs of economic green shoots around the world, with a corresponding rise in international investment: as Figure 1.1 shows, 2010 saw inflows rise modestly to just under US$1.31 trillion, while the pace of recovery quickened slightly in 2011, which saw inflows rise by more than 16 per cent to just over US$1.52 trillion,3 slightly above the pre-crisis average during 2005–2007.

In spite of these promising signs, it would be far too optimistic to say that we are on the fast track to a full recovery. Ongoing concerns around double-dip recessions and uncertainties around the nature and speed of recovery in various countries and regions (referred to by many in the business and political worlds as the ‘LUV’-shaped recovery4) mean that many would-be international investors are continuing to postpone investments until the macroeconomic situation becomes clearer and more stable.

A counterbalance to this cautious stance, however, is the perceived need among some companies to grow their businesses in new markets with lower costs and more dynamic consumption. Of those companies continuing to invest in this uncertain economic climate, access to new markets and capacity-building in preparation for the economic rebound are the two most important drivers of investment decisions, according to A.T. Kearney’s 2010 FDI Confidence Index.5 The firm’s more recent 2012 Confidence Index found that more than a third of investors were increasing their investments in emerging markets.6

Figure 1.1 Global FDI flows, average 2005–2007 and 2007–2011

Source: World Investment Report 2012, UNCTAD

This first chapter examines those locations around the world that now inspire confidence among investors, as well as those erstwhile FDI hotspots which have now fallen out of favour with the international investment community, and ultimately seeks to shed light on the reasons behind their respective successes and declines.

ASIA CONTINUES TO STEAM AHEAD

In broad terms, the Asia-Pacific region seems to have been at the forefront of investors’ minds over the past few years. Market research conducted by fDi Intelligence in early 2010 indicated that Asia-Pacific was the top destination region in 2009, while in A.T. Kearney’s 2010 FDI Confidence Index, 72 per cent of respondents believed that the region would lead the world out of recession.7 Two of the top three markets in the firm’s 2012 index are also from Asia-Pacific – unsurprisingly, these are the region’s two economic powerhouses, China and India, which came in first and second place respectively.

The leadership of China and India when it comes to investor interest and FDI flows is likely to continue unabated for the foreseeable future; their market potential as the world’s two distinctly most populated countries, coupled with their ongoing investments in infrastructure, higher education and a host of other FDI attributes, will ensure that they not only remain major FDI targets (that is, ‘host economies’), but will also increasingly become sources of FDI (or ‘home economies’). China was the second largest recipient of FDI in 2009, and by 2011 featured among the top five investors in the world.8

There has been much speculation over where the world’s most populous country and second global economy is headed over the next couple of decades, and what this will entail for FDI. Some statistics have pointed to a potential slowing down of FDI into China – for example, at the end of 2011, inflows declined by 9.7 per cent in November and 12.7 per cent in December, according to China’s Ministry of Commerce,9 and with rising wages and costs, questions are increasingly being raised around the country’s long-term prospects for cost-saving FDI. This is only one small part of the broader FDI perspective, however, and for those investors seeking access to China’s vast and rapidly urbanising consumer markets, those rising wages are not an impediment, but rather an opportunity. And that opportunity is immense, stretching far beyond the well-known cities and provinces on China’s coast (Shanghai, Guangzhou, Hong Kong and so on). The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) pointed out in its recent report on FDI into China that a major westerly shift was taking place within the country: in 2007, the south-western city of Chongqing ranked just twenty-second out of China’s 31 provinces for FDI, but by 2011, it had overtaken the capital, Beijing.10

India’s prospects are also extremely bright as a foreign investment location. While it went from second to third place in A.T. Kearney’s 2010 Confidence Index (swapping places with the United States), it reclaimed second position in the company’s 2012 index11 (while the US moved down to fourth place). India featured among the top ten host economies in 2009, attracting US$35.6 billion of FDI inflows,12 and while the country’s inflows fell dramatically in 2010 to US$24.2 billion,13 2011 saw a significant upturn, with investment levels rising by more than 30 per cent to US$31.6 billion.14 The legacy of the 2010 Commonwealth Games, hosted by Delhi, is sadly likely to remain somewhat tainted by those shocking images of that collapsed footbridge and the insalubrious bathrooms and stray dogs on beds in the athlete’s village. Stories and images such as these carry great potency and tend to engender implications far beyond the realities behind them. Perception is reality, as the old maxim goes. And yet India’s realities have the potential to portray a far more promising image of a country which is the world’s largest democracy and whose rate of growth could possibly overtake that of China within the next few years. India’s innovative and entrepreneurial attributes are numerous and impressive: the country has pioneered the US$2,000 car and affordable surgery, while its major corporations are truly global players with business empires that stretch well beyond India’s borders. Such innovation and entrepreneurialism benefit not only India’s outward investment, but are also major inward investment attributes as the global economy becomes more knowledge-intensive.

BRITANNIA NO LONGER RULES THE WAVES (BUT HOPEFULLY THE UK CAN CONTINUE TO RIDE THEM)

The upward trends being witnessed in China and India – whose inflows started picking up as early as mid-2009 – contrast starkly with those being witnessed in much of the developed world. Investor confidence in the United Kingdom is reported to have fallen significantly since the crisis began (from fourth place in 2007 to tenth place in 2010, recovering slightly to eighth place in 2012).15 This overall decline in confidence over the past five years is reflected in the country’s disappointing FDI inflows, which shrank by 50 per cent during 2008–2009, only to fall a further 35 per cent in 2010, although 2011 did see a modest rebound of 7 per cent.16 Meanwhile, the decline in the country’s profile as an international investor was even starker following the onset of the crisis (with outflows falling from US$161 billion in 2008 to just US$44 billion in 2009, while by 2010 they had shrunk even more to US$39 billion, which was roughly on par with Spain’s outward FDI flows and lower than those of far smaller European economies like the Netherlands, Belgium and Switzerland).

This mixed five-year picture of FDI confidence and activity in the UK can be attributed to a number of factors, not least the fact that it was one of the first countries to fall victim to the financial crisis which exploded in late 2008. The UK economy’s heavy dependence on the financial services industry exposed the country more than many to the turbulence of what was, with few exceptions, a global crisis. Investor confidence in the City of London slumped, and as the British government came in to prop up the banks and subsequently introduce legislation that would rein in the activities of investment banks and other financial actors, investors started questioning the future ease of doing business in a country which for more than a century has been seen as a bastion of the free market economy. The country had furthermore been in election mode ever since Gordon Brown pondered calling an election in the autumn of 2007. His decision not to proceed with an election that year, followed by the onset of the financial crisis in 2008, generated a long-lasting sentiment that an election was just around the corner (it was due to be held by May 2010 at the latest), and would strongly reflect the British people’s judgement on how the government had handled the economic crisis. By late 2009, a landslide victory for David Cameron’s Conservative Party was appearing increasingly unlikely, and prospects for a hung parliament – never an investment attribute – seemed increasingly feasible.

The UK’s heavy dependence on the rest of Europe for trade is another part of the story, and to some extent explains why it has performed much worse on the FDI front than, say, the United States, which was also particularly hard hit by the recession and which we’ll come to later. Investors in Europe have been far more reticent than those in other parts of the world over the past few years; A.T. Kearney’s 2010 index revealed that 62 per cent of European companies were planning to postpone investments, compared with just 46 per cent in North America and 42 per cent in Asia-Pacific.17 The economic crises that have beset Greece, Spain and smaller economies like Latvia, Ireland and Hungary have done nothing to boost investor confidence in Europe either, and on the contrary have had serious repercussions across the Continent (including in the City and other financial centres). When it comes to preferred locations among European investors, A.T. Kearney’s 2010 report found that the UK did not even figure among the top ten countries (while other major European economies like Germany, Italy and France all did).18 However, as the country’s economy begins to show signs of recovery and the UK coalition government continues to tackle the budget deficit, there’s hope that investor confidence – and activity – in the country will begin to grow once more.

The effects of the economic downturn have reminded us that geography is key, as are the strategic partnerships which countries, regions, cities and companies alike forge to leverage their geographic advantages. If your neighbours are doing well, then you should fully leverage this to your advantage, as research suggests that companies prefer to invest closer to home.19 If they’re not doing so well, this may on the one hand give your country a competitive advantage within that region. However, you should also consider whether regional investors will have the appetite or confidence to invest abroad, and you might need to consider looking at other regions where economic prospects are brighter and investor confidence is higher.

RUSSIA: THE UNDERPERFORMING BRIC?

The sluggish economic growth we’re currently seeing across much of Europe is one of the core factors behind the disappointing levels of investor confidence and activity not only in developed European countries, but even in major emerging markets like Russia, where FDI inflows dropped from US$75 billion in 2008 to just US$36.5 billion in 2009 – the greatest drop of all the founding BRIC markets.20 Flows have since started to recover, reaching US$43 billion in 2010 and rising to just under US$53 billion in 2011.21 The gap compared to pre-crisis levels therefore remains significant.

The wavering levels of FDI inflows to Russia over the past few years can arguably be attributed to various factors – some of which are regional and even global, while others are national. A slump in cross-border merger and acquisitions (M&A) activity by European firms, coupled with a drop in demand at home, were prime contributors to the initial decline, and yet Russia’s importance as a source and target of investment remains high – it ranked eighth in UNCTAD’s lists of both host and home economies in 2010.22 It was also the first of the BRIC countries to become a net outward investor.

While these economic figures portray a relatively sound picture of a country which has seemin...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures and Table

- About the Author

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 FDI in a Downturn: Trends and Lessons Learned

- 2 Place Brands: ‘Guarantors’ of Investment

- 3 Protectionism and Neo-imperialism

- 4 The Investor Perspective

- 5 Politics and Public Diplomacy

- 6 Where Next for FDI?

- Bibliography

- Index