eBook - ePub

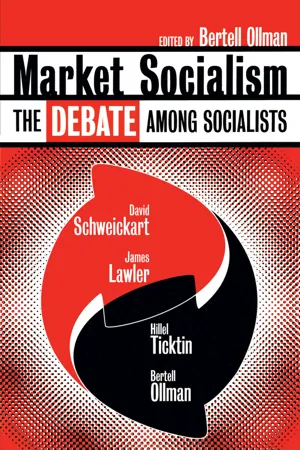

Market Socialism

The Debate Among Socialist

- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Market Socialism

The Debate Among Socialist

About this book

Aside from Post Modernism, probably the hottest topic today among socialist scholars world-wide is Market Socialism. In this book, four leading socialist scholars present both sides of the debate--two for, and two against--highlighting the different perspectives from which Market Socialism has been viewed. Arguing in favor of Market Socialism are the philosophers David Schweickart and James Lawler. While opposing them and Market Socialism are the political economist Hillel Ticktin and the political theorist Bertell Ollman. The evidence and arguments found in this book will prove invaluable to readers interested in the future of socialism.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Market Socialism by David Schweickart,James Lawler,Hillel Ticktin,Bertell Ollman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

for

1.

Market Socialism: A Defense

DAVID SCHWEICKART

It is not à la mode these days to advocate socialism of any sort. The pundits have stopped repeating the mantra that socialism is dead and that liberal capitalism is the telos of history. This is no longer news. It is an accepted "fact." Socialism is dead.

The death certificate has been signed not only for classical command socialism but for all versions of market socialism as well, with or without worker self-management. Hungarian economist Janos Kornai, once an advocate of market socialism, now confidently asserts:

Classical socialism is a coherent system... . Capitalism is a coherent system... . The attempt to realize market socialism, on the other hand, produces an incoherent system, in which there are elements that repel each other: the dominance of public ownership and the operation of the market are not compatible.1

As for self-management, "it is one of the dead-ends of the reform process."2

There are at least two good reasons, one theoretical, the other empirical, to dissent from Kornai's fashionable wisdom. First of all, there has developed over the last twenty years a large body of theoretical literature concerned with market alternatives to capitalism that reaches a different conclusion.3 Secondly, the most dynamic economy in the world right now, encompassing some 1.2 billion people, is market socialist.

China

If it is not fashionable to defend socialism these days, it is even less so to defend China. At least on the left there remain some stalwart defenders of socialism, but left, right, or center, no one likes China. In China there are executions, human rights violations, lack of democracy, workers working under exploitative conditions, misogyny, environmental degradation and political corruption. Moreover, China projects no compelling internationalist vision that might rally workers of the world or the wretched of the earth.

China is not inspirational now the way Russia was in the aftermath of the Bolshevik Revolution, or as China was for many on the Left in the 1960s or as Vietnam or Nicaragua or Cuba have been. One wishes that the defects of Chinese society were not so glaring.4 There is a role for Utopian imagery in a political project such as socialism. We need stirring visions. We need to be able to imagine what is, as yet, "nowhere." Yet there is also a need for realism in assessing the accomplishments and failures of actual historical experiments. Since there are few experiments more momentous than what is now transpiring in China, we need to think carefully about what can and cannot be deduced from the Chinese experience.

If by "socialism" we mean a modern economy without the major means of production in private hands, then China is clearly a socialist economy. Not only does China describe itself as "market socialist," but the self-description is empirically well-grounded. As of 1990, only 5.1 percent of China's GNP was generated by the "private" sector.5 And despite considerable quantities of foreign capital flowing into the country (mostly from Hong Kong and Taiwan, mostly into joint ventures), that portion of Chinese investment in fixed assets utilizing funds from abroad is only thirteen percent (as of 1993), and employs barely four percent of the non-agricultural workforce, some five or six million workers. By way of contrast, there were, as of 1991, some 2.4 million cooperative firms in China, employing 36 million workers, and another 100 million workers employed in state-owned enterprises.

This "incoherent" market socialist economy has been strikingly successful, averaging an astonishing ten percent per year annual growth rate over the past fifteen years, during which time real per capita consumption has more than doubled, housing space has doubled, the infant mortality rate has been cut by more than fifty percent, the number of doctors has increased by fifty percent, and life expectancy has gone from sixty-seven to seventy And on top of all this, inequality, as measured by the Gini coefficient, has actually declined substantially—due to the lowering of the income differential between town and country.6 Even so skeptical an observer as Robert Weil, who taught at Jilin University of Technology in Changchun in 1993, concedes:

Changchun university students, who come even from poorer peasant backgrounds, speak of the transformation of their villages, with investments in modern farm implements and new consumer goods. For the working people in the city who until a year or so ago had to live through the winter on cabbage and root crops and buy what few other vegetables and fruits were available off the frozen sidewalks, the plethora of bananas, oranges, strawberries, greens and meats of all kinds that can now be purchased in indoor markets year round has changed their lives and their diet. Across the nation meat consumption per capita has increased some two and a half times since 1980. Millions of workers have gained new housing during "reforms," [the scare quotes are Weil's] built by their enterprises, so that the two or three families that used to share a single apartment now each have their own homes. Within the last few months, the work week in state owned firms has been lowered from forty-eight hours to forty-four, a major and widely welcomed improvement.7

The empirical evidence does not suggest that China is Utopia. It is far from that. Critics are not wrong to be concerned about human rights violations, the lack of genuine democracy, worker exploitation (evidenced by, among other things, a horrendous rate of industrial accidents), the markedly higher infant mortality rates for girls than for boys, environmental degradation and widespread corruption. Nevertheless, China's real accomplishments have been stunning. If socialism is an emancipatory project concerned with improving the real material conditions of real people, and not an all-or-nothing Utopianism, then socialists of good will (particularly those of us who have regular access to bananas, strawberries, greens, and meat) should not be too quick to dismiss these accomplishments.

Moreover, China's developmental trajectory remains unclear. It is possible that the contradictions of Chinese socialism will intensify to the point of social explosion. It is also possible that China will one day enter the ranks of capitalism. But those who maintain the inevitability of one or both of these eventualities are, it seems to me, reading tea leaves. We do not yet know how the Chinese experiment will come out. China may remain master of the productive energies it has unleashed, and may move to democratize itself and to address its other grave deficiencies. This too is possible.

In any event, to maintain in the face of such powerful evidence to the contrary that market socialism is unworkable is surely problematic. The Eastern European economists who so confidently made such assertions and who so wholeheartedly embraced the privatization and free-marketization of their own economies would do well to compare the wreckage induced by their reforms to what a market socialism has wrought.

What is Market Socialism?

China demonstrates that a form of market socialism is compatible with a dynamic economy that spreads its material benefits broadly. But China is too complex a phenomenon, too much shaped by historical and cultural contingencies, too much in flux, for one to draw many firm conclusions. In order to go beyond the mere assertion of possibility it is more fruitful to engage the market socialism debate at a more theoretical level.

I wish to defend a two-part thesis: (a) market socialism, at least in some of its versions, is a viable economic system vastly superior, as measured by norms widely held by socialists and non-socialists alike, to capitalism, and (b) it is the only form of socialism that is, at the present stage of human development, both viable and desirable. Non-market forms of socialism are either economically non-viable or normatively undesirable, often both at once.

Let us be more precise about the meaning of "market socialism." Capitalism has three defining institutions. It is a market economy, featuring private ownership of the means of production and wage labor. That is to say, most of the economic transactions of society are governed by the invisible hand of supply and demand; most of the productive assets of society belong to private individuals either directly or by virtue of individual ownership of shares in private corporations; most people work for salaries or wages paid directly or indirectly by the owners of the enterprises for which they work. A market socialist economy eliminates or greatly restricts private ownership of the means of production, substituting for private ownership some form of state or worker ownership. It retains the market as the mechanism for coordinating most of the economy, although there are usually restrictions placed on the market in excess of what is typical under capitalism. It may or may not replace wage labor with workplace democracy, wherein workers get, not a contracted wage, but specified shares of an enterprise's net proceeds. If it does, the system is a "worker-self-managed" market socialism.

Various theoretical models of market socialism have been proposed in recent years, but all advocates of market socialism agree on four points.

- The market should not be identified with capitalism.

- Central planning is deeply flawed as an economic mechanism.

- There exists no viable, desirable socialist alternative to market socialism; that is to say, the market is an essential (if imperfect) mechanism for organizing a viable economy under conditions of scarcity.

- Some forms of market socialism are economically viable and vastly preferable to capitalism.

Let us examine each of these contentions.

The “Market = Capitalism” Identification

The identification of capitalism with the market is a pernicious error of both conservative defenders of laissez-faire and most left opponents of market reforms. If one looks at the works of the major apologists for capitalism, Milton Friedman, for example, or F. A. Hayek, one finds the focus of the apology always on the virtues of the market and on the vices of central planning.8 Rhetorically this is an effective strategy, for it is much easier to defend the market than to defend the other two defining institutions of capitalism. Proponents of capitalism know well that it is better to keep attention directed toward the market and away from wage labor or private ownership of the means of production.

The left critique of market socialism tends to be the mirror image of the conservative defense of capitalism. The focus remains on the market, but now on its evils and irrationalities. In point of fact, it is as easy to attack the abstract market as it is to defend it, for the market has both virtues and vices. Defenders of capitalism (identifying it as simply "a market economy") concentrate on the virtues of the market, and dismiss all criticisms by suggesting that the only alternative is central planning. Critics of market socialism concentrate on the vices and dismiss all defenses by suggesting that models of market socialism are really models of quasi-capitalism. Such strategies are convenient, since they obviate the need for looking closely at how the market might work when embedded in networks of property relationships different from capitalist relationships—convenient, but too facile.

The Critique of Central Planning

It must be said that conservative critics have been proven more right than wrong concerning what was until relatively recently the reigning paradigm of socialism: a non-market, centrally-planned economy. They have usually been dishonest in disregarding the positive accomplishments of the experiments in central planning, and in downplaying the negative consequences of the market, but they have not been wrong in identifying central weaknesses of a system of central planning, nor have they been wrong in arguing that "democratizing" the system would not in itself resolve these problems.

The critique of central planning is well-known, but a summary of the main points is worth repeating. A centrally-planned economy is one in which a central planning body decides what the economy should produce, then directs enterprises to produce these goods in specified quantities and qualities. Such an economy faces four distinct sets of problems: information problems, incentive problems, authoritarian tendencies, and entrepreneurial problems.9

As for the first: a modern industrial economy is simply too complicated to plan in detail. It is too difficult to determine, if we do not let consumers "vote with their dollars," what people want, how badly, and in what quantities and qualities. Moreover, even if planners were able to surmount the problem of deciding what to produce, they must then decide, for each item, how to produce it. Production involves inputs as well as outputs, and since the inputs into one enterprise are the outputs of many others, quantities and qualities of these inputs must also be planned. But since inputs cannot be determined until technologies are given, technologies too must be specified. To have a maximally coherent plan, all of these determinations must be made by the center, but such calculations, interdependent as they are, are far too complicated for even our most sophisticated computational technologies. Star Wars, by comparison, is child's play.

This critique is somewhat overstated. In fact planners can plan an entire economy. Planners in the Soviet Union, in Eastern Europe, in China and elsewhere did exactly that for decades. By concentrating the production of specific products into relatively few (often huge) enterprises and by issuing production targets in aggregate form, allowing enterprise managers flexibility in disaggregation, goods and services were produced, and in sufficient quantity to generate often impressive economic growth. It is absurd to say, as many commentators now do, that Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich Hayek have been proven right by events, that a centrally-planned socialism is "impossible." To cite only the Soviet Union: an economic order that endured for three-quarters of a century in the face of relentless international hostility and a German invasion, and that managed to industrialize a huge, quasi-feudal country, to feed, clothe, house and educate its citizenry, and to create a world-class scientific establishment should not be called "impossible."

However, the opposite of "impossible" is not "optimal." The Soviet economy and those economies modeled on Soviet economy always suffered from efficiency problems, and these became steadily worse as the economies developed. Information problems that were tractable when relatively few goods were being produced, and when quantity was more important than quality, became intractable when more and better goods were required. It is not without reason that every centrally planned economy has felt compelled to introduce market reforms once reaching a certain level of development.10

In theory a non-market socialism can surmount its information problems. In theory markets can be simulated. Planners can track the sale of goods, adjust prices as if supply and ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half-Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Participants in the Debate

- Introduction

- Part One for

- Part Two against

- Part Three criticism

- Part Four response

- Select Bibliography on Market Socialism

- Index