![]()

Part I

![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

Art therapy is rooted in the regeneration that followed the Second World War. Since then, the profession has thrived, spreading out into a variety of contexts. Beginning at the roots of art therapy in the UK, this chapter follows the branch of its evolution associated with the armed forces up to contemporary practice. Attention is given to the use of art as part of rehabilitation in military hospitals, and connections are made with the growth of art therapy at the UK veterans’ mental health charity Combat Stress. Currently, Combat Stress is a key provider of art therapy within specialist veterans’ services. Remembrance and ritual are seen to play a part in recovery, and to provide a way for the wider public to acknowledge the sacrifices made through military service. The focus is then turned towards art therapists working within the field of trauma, and the benefits and challenges of working in this context are explored. The possible effects of war stories, the concept of vicarious traumatisation and the likelihood of encountering prejudice towards the military are all examined as part of the complexities of working with this client group.

War art to art therapy

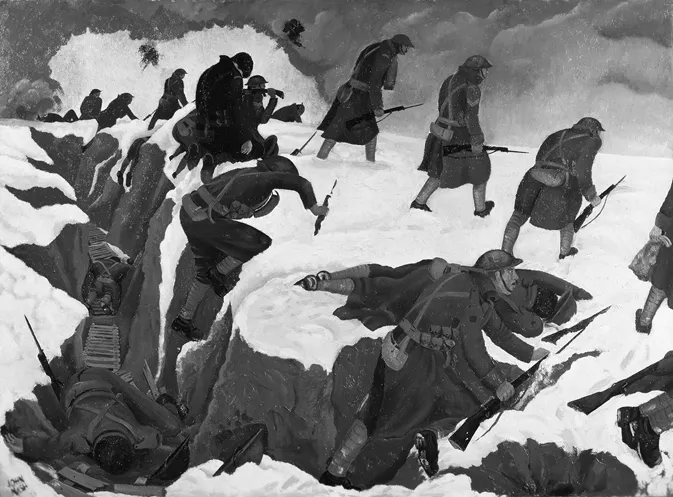

On the bitterly cold morning of 30 December 1917, the 1st Artists Rifles were ordered to push forward at Welsh Ridge, Marcoing towards Cambrai, in response to an attack. Of the 80 men present, 68 were soon killed by a barrage of machine gun fire. One of the 12 survivors was John Nash, who captured the experience in the officially commissioned painting Over the Top a few months later (Figure 1.1). The exhausted unit had been recalled from rest at the support line and had to mount the hurried counter-attack upon arrival at the front line, with tragic consequences. The painting is unusual as it captures an actual event (Clark, 2014).

It is the vulnerability of the hunched soldiers going ‘over the top’ that seems so shocking as they walk forwards exposed to enemy fire. They stand out clearly against the whiteness of the snow with no shields or armour to protect them, only ‘tin hats’. Their weapons are not raised to fire and one soldier is carrying his rifle on his shoulder. Already several soldiers have been shot. One soldier kneels slumped, his helmet on the ground in front of him, having barely left the trench. His comrades’ focus is forwards, with no attention given to those falling around them. The painting serves as a chilling reminder of the great loss of life experienced by all sides, the sacrifice of individuals, and the inevitable consequences on families and communities.

What was to become the Artists Rifle Regiment was established in 1860 as part of the Volunteer Corps. Its early headquarters were at the Royal Academy, Burlington House. Founder members included artists G. F. Watts, John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt, Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris. Frederick Leighton was one of the early commanders and John Ruskin was an honorary member. The Volunteer Corps was raised in 1859 in response to the threat of French invasion. Initially there seemed to be more of a social function to the Artists Rifles than military. However, by 1914 the regiment had become an officer training corps and its membership had broadened to include many other professions. Artists who served in the regiment during the Great War of 1914–1918 included Paul Nash, sculptor Frank Dobson, poet Wilfred Owen and playwright R. C. Sherriff. The Artists Rifles were disbanded in 1945, reformed in 1947 and currently form part of the Special Air Service Reserves (Christiansen, 2014; ‘Unit history: 21 Artist Rifles’, n.d.).

Both John Nash and his elder brother Paul became commissioned as official war artists. Paul Nash’s powerful paintings of devastated battlefield landscapes have become iconic of the era. The British government’s War Propaganda Bureau first set up a war artist’s scheme in 1916. By 1917, the remit had changed from propaganda to recording and memorialising events. The Imperial War Museum (IWM) was established that year and was tasked by the Department of Information to document the war. The Museum also commissioned its own war artists, the first of whom was Adrian Hill (Smalley, 2016).

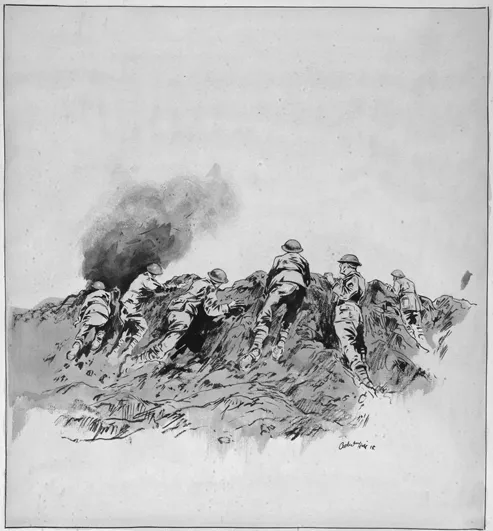

Adrian Hill enlisted with the Artists Rifles in November 1914 as it seemed the natural choice, being an art student at the time, but he transferred to the Honourable Artillery Company after encouragement to do so from his brother (Hill, 1975). While serving on the Western Front, he was often sent into ‘no man’s land’, the area between opposing forces, on scouting missions to sketch the enemy position. Later as an official war artist, he created 180 pen and ink drawings of the troops and their environment between 1917 and 1919, which are stored in the IWM, London (Gough, 2010). One of his drawings Shelling Back Areas has the subtitle Where Did That One Go? referring to a song that was popular at the time (Figure 1.2). It depicts six hunched soldiers looking over a shallow, churned-up ridge of earth in the direction of an explosion. The implied randomness of the shelling and the lack of cover underline the vulnerability of the soldiers, but the subtitle also suggests that humour was used to moderate the sense of threat. This resonates with battlefield humour to this day.

After the war was over, like everyone else, Hill attempted to get on with his life. He had studied art at St John’s Wood Art School before the war, from 1912 to 1914, and decided to complete his studies at the Royal College of Art during 1919–20. He then became a practising artist and educator. In 1938, he contracted pulmonary tuberculosis and went to convalesce at King Edward VII Hospital, Midhurst (Hogan, 2001; Waller, 1991).

It is at this point, following the aftermath of the First World War and on the brink of the Second World War, that the concept of art therapy entered the arena. It is Adrian Hill who is attributed as the originator of the term ‘art therapy’. Art played a significant part in Hill’s recovery from tuberculosis. Through the IWM’s invaluable archives, it is possible to listen to Hill’s own verbal account of his war-time experiences and the part art played in his recovery from tuberculosis. He refers to himself as an ‘unwilling person who had got to rest’ and how the enforced rest made him feel as though he was ‘shirking’ (Hill, 1975, Reel 5). While immobilised in bed, he drew objects around him and seemed to tap into something so valuable that he wanted to share it with others who were in recovery. As an ambulant patient, he turned his attention towards other patients at the sanatorium and enthusiastically encouraged them to paint. By 1941, King Edward VII Hospital began taking war casualties and Hill was invited to be involved in their care. He did not view art therapy as offering something diversional or recreational but as providing a way to access the source of their difficulties (Hogan, 2001).

Hill became a tireless promoter of art therapy. Benefits could be gained not only from art-making but also art appreciation. He gave lectures on art to patients using prints. These echoed observations by nursing pioneer Florence Nightingale in the previous century. In her Notes on Nursing (1860), she wrote about the beneficial effects of colour, form and light towards the healing of body and mind. She promoted the gradual introduction of engravings to be hung near the hospital bed to promote recovery (BJN, 1946; Nightingale, 1860). In 1945, Hill’s book Art verses Illness was published. It seems to have been well received, as a review in The British Journal of Nursing recommended that ‘it should be placed in every sanatorium and hospital library’ (BJN, 1946, p. 16).

Art therapy is associated with the post-war rehabilitation movement (Waller & Gilroy, 1992). Hill and fellow pioneers such as Edward Adamson played a key role in establishing the foundation of art therapy in Britain. Both Hill and Adamson were involved in the British Red Cross Picture Library, which offered a lending scheme for taking reproductions of artwork into hospitals and providing associated lectures. The benefits of viewing art will be explored further in Chapter 12.

Art activities to art therapy in military hospitals

The Royal Victoria Military Hospital, Netley, Hampshire was founded in 1856 in response to the Crimean War. It was an enormous site, being a town in itself, complete with gasworks, prison and a reservoir (Hoare, 2001). It housed the first military asylum, built in 1870, and half those diagnosed with ‘shell shock’ during the First World War passed through there. News clips capture the effects of war neurosis on Netley patients and the process of recovery (British Pathé News, 1917–1918). Later, in 1953, radical psychiatrist R. D. Laing, who had worked at Netley when conscripted into the British Army in 1951, wrote that art therapy had been one of the treatments available during his time there, but no details are provided (Beveridge, 2011).

The huge need for hospital and rehabilitation services fuelled by the unprecedented volume of war injured during the First World War of 1914–1918 saw the establishment of more specialist military hospitals. Many stately homes were requisitioned to act as temporary hospitals. Craiglockhart War Hospital, Edinburgh was formerly Craiglockhart Hydropathic Institution, a health spa hotel, before becoming a psychiatric hospital for Army officers from 1916 to 1919. It was there that psychiatrist and psychoanalyst W. H. R. Rivers pioneered the use of talking therapy to treat shell shock and neurasthenia. Perhaps two of the best-known patients were poets Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen. Shell shock is further considered in Chapters 4 and 5 of this book.

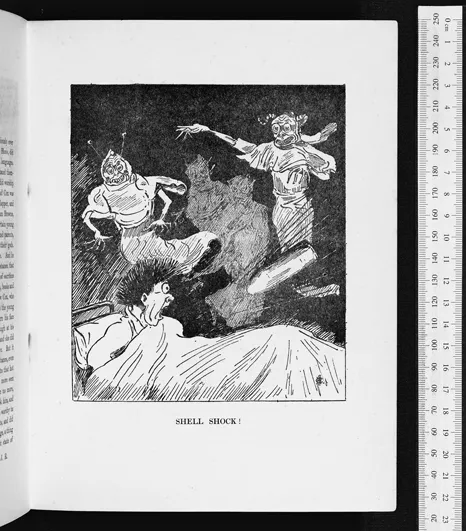

A journal called The Hydra was produced by patients at Craiglockhart and featured short stories, articles, advertisements, poems, prints and the occasional sketch. The sketches are usually satirical but the December 1917 edition contains a striking image of Shell Shock! (Figure 1.3). It shows someone in bed suddenly sitting up, looking terrified by ghostly monsters and about to be hit by a shell. It has a resonance with work currently produced by veterans as part of art therapy. For instance, Figure 1.4 depicts three shadowy, armed figures standing at the foot of the coffin-like bed of a veteran. The haunting emotions and body sensations of trauma find expression through both images.

In January 1918, a Fine Arts Club was started at Craiglockhart in association with Edinburgh College of Art. In the July 1918 edition of The Hydra, Secretary W. G. Shearer draws readers’ attention to the arts and crafts classes that were available, which included painting, decorative pottery and wood carving. It seems that pottery painting was the most popular class (‘Arts and crafts’, 1918). The arts and crafts approach to rehabilitation was fostered at other hospitals too during the First World War. However, at Hollymoor Hospital, Northfield, Birmingham a new approach to art-making was to emerge during the Second World War.

The ‘Northfield Experiments’ are acknowledged as having played a crucial role in the development of group psychotherapy and the therapeutic community movement (Harrison & Clarke, 1992). In 1940, Wilfred Bion began to explore the idea of ‘using all the relationships and activities of a residential psychiatric centre to aid the therapeutic task’ (Bridger, 1990, p. 68). He was given the opportunity to put theory into practice in 1942 at Hollymoor Hospital with troops returning home traumatised by war. This was with a view to enabling them to return to active military service. Bion and John Rickman used group dynamics to promote recovery. However, the First Northfield Experiment, as it became known, was not well received due to the chaos it caused, and it only lasted six weeks. Ideas were developed and revised, leading to the Second Northfield Experiment, led by Sigmund Foulkes, Tom Maine and Harold Bridger. This proved more successful (Harrison & Clarke, 1992).

Sergeant Laurence Bradbury of the Royal Engineers was attached to the Army Education Corps and posted to Northfield in 1944 to set up an art group as part of occupational therapy. In audio recordings made in 1998 and now held at the IWM (Bradbury, 1998), Bradbury shares his opinion that the group he established in the ‘Art Hut’ had nothing to do with the approach taken by occupational therapy. He states that the art made in the group was ‘not deflecting and trying to get people to forget the injury to their mind but rather to face up to it’ and he was ‘given lease to do it’ without any prior experience. He refers to the space as the ‘little hut of mayhem’ where patients could express themselves rather than let problems fester. There was no rank system in the Art Hut and patients were given freedom of expression, which resulted in a ‘form of anarchy’ and mess (ibid.). Sometimes there were fights or work was destroyed. Bradbury allowed the tension to build without taking responsibility for addressing the anxieties or mess and eventually the patients would decide to clear up (ibid.; Harrison, 2000).

Bradbury was convinced that it was the process of free expression and allowing people to ‘be themselves’ that helped (Bradbury, 1998). He painted with the patients and did not take a lead, nor did he require any prior knowledge of the patients. He sensed resentment from some other staff members for allowing the mayhem, with concern that it might spread, and that some considered this approach an indulgence. Dr Foulkes would visit the group once a week and artwork would be spread over a table. Everyone sat quietly until someone broke the silence. Bradbury describes how ‘heartrending’ it was to witness the grief expressed and that he learned by observation (ibid.). He was not an advocate of interpreting patient’s work.

Dr Eric Cunningham Dax, Medical Superintendant of Netherne Psychiatric Hospital, Surrey visited Northfield on several occasions and it seem...