eBook - ePub

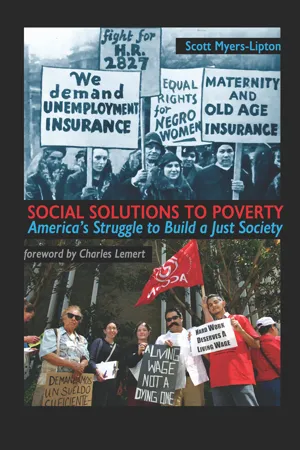

Social Solutions to Poverty

America's Struggle to Build a Just Society

- 360 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Social Solutions to Poverty

America's Struggle to Build a Just Society

About this book

The voices of famous and lesser known figures in America's quest to reduce poverty are collected for the first time in this comprehensive historical anthology. The book traces the most important ideas and contributions of citizens, activists, labour leaders, scholars, politicians, and governmental agencies to ensure American citizens the basics of food, housing, employment, education, and health care. The book follows the idea of poverty reduction from Thomas Paine's agrarian justice to Josiah Quincy's proposal for the construction of poorhouses; from the Freedmen's Bureau to Sitting Bull's demand for money and supplies; from Coxey's army of the unemployed to Jane Addams's Hull House; from the Civil Works Administration to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s call for an Economic Bill of Rights; and from William Julius Wilson's universal programme of reform to George W. Bush's armies of compassion.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Painting of a Huron (Wyandot) couple from the 1700s

Chapter 1

Native American Contributions to Egalitarianism

Prologue: Social Context and Overview of Solutions

Americans from the United States are rightfully proud of the opening lines of the Declaration of Independence, which assert that all people are created equal. However, this American belief in equity, which would inspire social reformers and social justice advocates in the United States and around the world, is not grounded solely in European philosophy. Rather, a strong argument can be made that the American notion of egalitarianism entered modern social thought as a result of European and Euro-American thinkers being challenged by the equality of Native American society, and as a result, a new way of thinking emerged.

The fact is that European cultures did not have a deep commitment to equality or freedom at the time of the American Revolution, as European societies were highly stratified by social class. Thomas Jefferson, the author of the Declaration of Independence, believed that Europe was divided into two classes, the rich and the poor, and that under the pretense of governing, the former took advantage of the latter, as wolves prey on sheep. The historian Henry Steele Commager added that “everywhere Europe was ruled by the wellborn, the rich, the privileged, by those who held their places by divine favor, inheritance, prescription or purchase.”1

The European belief that the wealthy were superior to the poor is revealed when one examines who was allowed to participate in political affairs. In late eighteenth-century England, only 1 in 20 men could vote, and in Scotland, only 3,000 men could vote. Furthermore, egalitarian democracy, with its belief that since all were created equal then all should be allowed to participate in political affairs, did not develop in the other European colonies, whether it was in New Spain under the Spanish (the direct descendants of Roman language, custom, and religion), Haiti under the French, South Africa under the British, or Indonesia under the Dutch.2

To appreciate the great intellectual debt owed to Native Americans, it is necessary to look at what European and Euro-American intellectuals were writing at that time. After examining the record, the consistent theme is that Native Americans lived with a level of equality and freedom greater than that in European society. This theme can be seen in the writings of Europeans soon after contact was made in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, in the writings of Euro-Americans around the time of the American Revolution, and in the testimonies of Native Americans.

In one of the earliest descriptions to reach Europe, Michel de Montaigne, the French essayist, described what the first Europeans saw when they made contact with Brazilian indigenous society. Montaigne reported in 1575 that “Indian” society lacked poverty, riches, or inheritance, and that it was wrong to label this culture as savage or barbarian. Montaigne’s essay, as well as other initial postcontact commentaries that stressed egalitarianism, had a profound impact on European ideas about equity and what type of society was possible. For example, William Shakespeare used the words of Montaigne in The Tempest. In act 2, scene 1, the honest and aging counselor, Gonzalo, speaks about the ideal commonwealth; to describe it, Shakespeare used Montaigne’s description of Native America almost verbatim. Furthermore, Thomas More, the English politician, humanist scholar, and Catholic saint, wrote Utopia after reading the letters of Amerigo Vespucci. More’s Utopia, which described an earthly paradise where one has equality without money, was partly based on Vespucci’s description of American Indians’ egalitarianism. More’s book was seen as a direct challenge to European society to deal with its poverty and inequity.3

Over a century later, in 1703, Louis Lahontan reported details of a conversation he had with Adario, a Huron (Wyandot) male, where the latter described how American Indians lived in egalitarian relationships. According to Lahontan’s account, Adario was stunned by the high level of European poverty and repulsed by the inequality between rich and poor. Adario described Huron society as devoid of this type of inequality and argued that this would not be allowed among the Hurons. Some question the veracity of Lahontan’s account of the dialogue; others claim that although it may not have been recorded verbatim, it does contain significant truths about Native American life. Once again, these ideas had a strong effect on European society, as Lahontan became an international celebrity after his popular writings were adapted and made into a successful play in Paris in 1721. In fact, the theme of Native American life offering more equity and liberty was so popular in Europe that others copied it and produced additional plays, operas, farces, and burlesques on this same topic.4

In the period of the American Revolution, Europeans and Euro-Americans continued to be impressed with the level of equality in Native American society. St. John de Crèvecoeur described the American Indian way of life as superior to that of Europeans living in America, since indigenous people lived “with more ease, decency, and peace.” James Adair, who wrote The History of the American Indians in 1775, stated that in every Indian nation a person “breathes nothing but liberty” and lives with “an equality of condition, manners, and privilege.” Benjamin Franklin noted that this high degree of equity and freedom was the reason that many whites decided to go and live in Native American communities; at the same time, Franklin knew of no case where an Indian had chosen to live in white society. Franklin believed that Native Americans were disgusted by “civil society,” since it required “The Care and Labour of providing for Artificial and fashionable Wants, the sight of so many Rich wallowing in superfluous plenty, whereby so many are kept poor and distress’d for Want.” The absence of human suffering due to poverty in native communities can also be seen in the reflections of Buffalo Bird Woman, a Hidatsa born around 1839 in North Dakota, who told an interviewer that in the old times, “we had plenty to eat and wear then, abundance of meat and fur robes and tanned skins.”5

To achieve an egalitarian society required creative strategies. Some tribes dealt with economic inequality by redistributing their resources. For example, Lieutenant Governor Cadwallder Colden of New York observed that within the Iroquois Confederation, the most important men gave away the presents or rewards they received as part of treaties or war, and thus had fewer material goods than the common person. In addition, Colden discussed how the Five Nations did not believe in the superiority of one person over another, and how they had an absolute understanding of liberty. This lack of interest in attaining wealth over others was also noted by John Hunter, who observed in the early 1800s that the chiefs and other important people of the Plains tribes “render themselves popular by their disinterestedness and poverty.” The Plains Indians, in a similar way to the Iroquois, liberally distributed the property they had acquired. Hunter explained that the Plains Indian leaders “pride themselves in being estimated the poorest men in the community.”6

Many Native American communities also ensured a high level of economic equality by holding their land in common. Communal ownership of property ensured that all shared in the resources of society and that suffering due to lack of basic necessities was minimized. This focus on communal ownership of property led to a preoccupation with group relationships and generally a lack of central authority, which led to a high degree of freedom. Clearly, communal ownership of property was diametrically opposed to the European perspective, with its belief in private property, which has tended to fixate on commerce, competition, and the ultimate act of domination, war.7

It is true that not all of the more than 500 Native American tribes in the Western Hemisphere valued equity and liberty. For example, the Tlingit in the Pacific Northwest, the Natchez of the lower Mississippi Valley, and the Aztecs in Mesoamerica possessed stratified social class systems. At the same time, it is possible to say that the new European consciousness gained from Native Americans about the possibility of living in a society that was both equal and free allowed for a counterpoint to the “Old World.” Europeans and Euro-Americans had the opportunity to appraise theoretical ideas from the Enlightenment, like Locke’s notion of “liberty, equality, and property” and Rousseau’s “social contract,” in light of what they observed in Native American societies. As Bruce Johansen states, “They [the transplanted Europeans] found in existing native politics the values that the seminal European documents of the time celebrated in theoretical abstraction—life, liberty, happiness, and government by consensus, under natural rights, with relative equality of property.” What came out of this appraisal and reassessment led to the creation of a new philosophy of government based on equality and liberty. This may have given impetus to the American Revolution as it provided the founders of the country a living example of people who governed themselves with freedom and equality, living in a society not ruled by a monarch, but by the people.8

The effect of Native Americans on early America is evident in the work of Thomas Paine. Paine, the great intellectual and activist of the American and French Revolutions, was a keen student of Indian life. After observing that Native American life was a “continual holiday” in comparison with that of poor people in Europe, Paine was inspired to develop a poverty reduction plan. In Paine’s 1797 book, Agrarian Justice, he argued that “civilized” people should create a social order that was as equal and free as that of Native Americans. Paine called for the creation of a social insurance plan for the elderly and a onetime payment to men and women when they turned twenty-one years of age so as to ensure a good start in life. The money would come from a national fund to be financed by a 10 percent assessment on all land at the time of death of the owner. Paine felt this assessment was justifiable since before cultivation, all land was common property of the human race, and therefore, every landowner owed rent to society. Paine’s plan of “natural inheritance” attempted to give meaning to the words in the Declaration of Independence that all are created equal and born with an inalienable right to pursue happiness, which for Jefferson included economic security.9

Ironically, Paine and Jefferson as well as other prominent Americans argued that Native American political and economic development was less advanced than their own. Most Europeans and Euro-Americans claimed that Native Americans were living in a “natural” or “primitive” state, and thus were at a lower level of development. At best, some claimed that Native Americans were “noble savages” since they believed that Indian culture had many positive qualities, but it was still supposedly “uncivilized.” Ironically, the Native Americans who had inspired this new thinking about equity, with the belief in freedom from autocratic rulers and the privileged elite, were labeled primitive and uncivilized. Once they were deemed inferior, it was easy for white Americans to justify removing them from their land.

The European colonists began the process of taking Indian land as the two groups competed for resources such as places to plant, fish, and hunt. After the United States won its independence from Britain in the Revolutionary War, the process of moving Native Americans off the land continued. In 1783, the Continental Congress declared that Native Americans were a defeated enemy, as many of them had fought on the side of the British, thus forfeiting all rights granted under earlier territorial treaties. Congress announced a plan to move Native Americans to Canada or to areas beyond the Mississippi River. Many Indians actively resisted this decree, and their defiance came in forms ranging from petitions to the U.S. government to military action. One of these petitions was sent by a group of Wabash Indians in the summer of 1793 to the new U.S. government. In the petition, the Wabash came up with a “win-win” solution to the U.S. government’s plan to take the land, which was to give the money they were offering for the Wabash land instead to the poverty-stricken U.S. settlers. The Wabash argued that this would solve both the problem of losing their land to competition and the problem of poverty in the United States.10

In summary, when the Europeans arrived in the Western Hemisphere in 1492, there were approximately 75 million people on the two continents. In what is now the continental United States, it is estimated that there were 2 to 5 million people, in Alaska and Canada there were 2 million people, and in Mexico there were 7 million people. The holocaust that would follow over the next 400 years would devastate the Indian population. Most U.S. citizens have only a vague understanding of this holocaust. They have even less knowledge of the contributions that indigenous ideas have had on American and European social and political thought. I hope the readings in this chapter will contribute to a more accurate understanding of how the modern idea of democracy arose from the interaction of our founders with Native Americans.11

On Cannibals (1575)

Montaigne’s essay was one of the first to be read by Europeans about Indians in the Americas.

When King Pyrrhus invaded Italy, after he had surveyed the army that the Romans had sent out against him, drawn up in battle array, “I know not,” he said, “what barbarians these are” (for the Greeks so called all foreign nations), “but the disposition of this army that I see is in no wise barbarian.” The Greeks said the same of the army that Flaminius led into their country; and Philip, when he saw from a little hill the order and arrangement of the Roman camp in his kingdom under Publius Sulpicius Galba. Thus we see how we should beware of adhering to common opinions, and that we must weigh them by the test of reason, not by common report.

I had with me for a long time a man who had lived ten or twelve years in that other world which has been discovered in our time in the region where Villegaignon made land, and which he christened Antarctic France. This discovery of a boundless country seems to be worth consideration….

This man that I had was a simple, plain fellow, which is a nature likely to give true testimony; for intelligent persons notice more things and scrutinise them more carefully; but they comment on them; and to make their interpretation of value and win belief for it, they can not refrain from altering the facts a little. They never represent things to you just as they are: they shape them and disguise them according to the aspect which they have seen them bear; and to win faith in their judgement and incline you to trust it, they readily help out the matter on one side, lengthen it, and amplify it. It needs a man either very truthful or so ignorant that he has no material wherewith to construct and give verisimilitude to false conceptions, and one who is wedded to nothing. My man was such a one; and, besides, he on divers occasions brought to me several sailors and traders whom he had known on his travels. So I am content with this information, without enquiring what the cosmographers say about it….

Now, to return to what I was talking of, I think that there is nothing barbaric or uncivilised in that nation, according to what I have been told, except that every one calls “barbarism” whatever he is not accustomed to. As, indeed, it seems that we have no other criterion of truth and of what is reasonable than the example and type of the opinions and customs of the country to which we belong: therein [to us] always is the perfect religion, the perfect political system, the perfect and achieved usage in all things. They are wild men just as we call those fruits wild which Nature has produced unaided and in her usual course; whereas, in truth, it is those that we have altered by our skill and removed from the common kind which we ought rather to call wild. In the former the real and most useful and natural virtues are alive and vigorous—we have vitiated them in the latter, adapting them to the gratification of our corrupt taste; and yet nevertheless the special savour and delicacy of divers uncultivated fruits of those regions seems excellent even to our taste in comparison with our own. It is not reasonable that art should gain the preëminence over our great and puissant mother Nature. We have so overloaded the beauty and richness of her works by our contrivances that we have altogether smothered her. Still, truly, whenever she shines forth unveiled, she wonderfully shames our vain and trivial undertakings.

The ivy grows best when wild,

and the arbutus springs most beautifully in some lovely cave;

birds sing most sweetly without teaching.

and the arbutus springs most beautifully in some lovely cave;

birds sing most sweetly without teaching.

[Propertius]

All our efforts can not so much as reproduce the nest of the tiniest birdling, its contexture, its beauty, and its usefulness; nay, nor the web of the little spider. All things, said Plato, are produced either by nature, or by chance, or by art; the greatest and most beautiful by one or other of the first two, the least and most imperfect by the last.

These nations seem to me, then, wild in this sense, that they have received in very slight degree the external forms of human intelligence, and are still very near to their primitive simplicity. The laws of nature still govern them, very little corrupted by ours; even in such pureness that it sometimes grieves me that the knowledge of this did not come earlier, in the days when there were men who would have known better than we how to judge it. I am sorry that Lycurgus and Plato had not this knowledge; for it seems to me that what...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- 1 Native American Contributions to Egalitarianism

- 2 The Early Republic and Pre–Civil War America: Moral Cures, Poorhouses, and Structural Solutions

- 3 After the Civil War: The Rise of Labor and Scientific Charity

- 4 The (Un)Progressive Era

- 5 The Great Depression and the New Deal Era

- 6 The War on Poverty

- 7 Dismantling the New Deal and War on Poverty: Contemporary Solutions

- Notes

- Credits

- Index

- About the Author

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Social Solutions to Poverty by Scott Myers-Lipton,Charles C. Lemert in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.