eBook - ePub

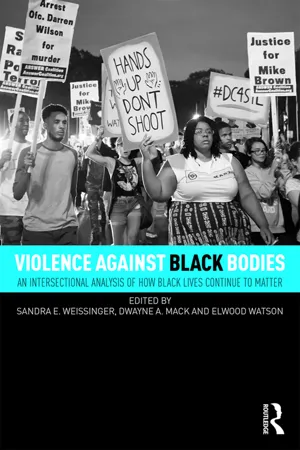

Violence Against Black Bodies

An Intersectional Analysis of How Black Lives Continue to Matter

- 294 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Violence Against Black Bodies

An Intersectional Analysis of How Black Lives Continue to Matter

About this book

Violence Against Black Bodies argues that black deaths at the hands of police are just one form of violence that black and brown people face daily in the western world. Through the voices of scholars from different academic disciplines, this book gives readers an opportunity to put the cases together and see that violent deaths in police custody are just one tentacle of the racial order—a hierarchy which is designed to produce trauma and discrimination according to one's perceived race and ethnicity.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Violence Against Black Bodies by Sandra E. Weissinger, Dwayne A. Mack, Elwood Watson, Sandra E. Weissinger,Dwayne A. Mack,Elwood Watson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

There Is No Time for Despair

(Re)Working the Racial Order

Over a century ago, Black intellectual extraordinaire of his day, W.E.B. DuBois, stated that the problem of the 20th century would be the problem of the color line. He was right on target. In 1944, the renowned Swedish sociologist Gunnar Myrdal wrote the landmark (for the time) An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy. Indeed, such a prophetic message is very relevant today in the 21st century. If the past several years (hell, the past several months for that matter) have taught us anything, it is that we as a nation are in a perpetual state of crisis when it comes to the racial situation plaguing our nation. To put it bluntly, the past several years have left a brash, brutal, ugly stain of racism, sexism, homophobia, classism and xenophobia on America and other parts of the world.

To be sure, our nation has seen worse times, given our collective and often tumultuous history. Nonetheless, 2015 and 2016 may very well become two years for the record books. In fact, as far as recent history (post-1985) is concerned, not since 1994 can I remember a time that has been this racially, sexually, culturally and religiously divisive.

From student unrest on college campuses; to politicians openly espousing racist, sexist, xenophobic rhetoric; attacks on affirmative action; economic wealth gaps not seen since the Gilded Age; heightened racial tension; to the ongoing murders of unarmed Black, Brown, gay, lesbian and transgendered people; and violence against women—America has witnessed back-to-back years that have been anything but tranquil. It seemed as if the nation was tackled to the ground by packs of grizzly bears, being mauled and unable to escape. To refresh your memory (although most of these events are likely to be firmly etched in your minds), here are just some of people and events that greeted us and made headlines in 2015 and 2016:

- Donald Trump has confounded the pundits, critics and many others with his unexpectedly successful presidential campaign. Along the way, however, he had stoked the fires of jingoism, regressive populism, xenophobia, hatred and other sorts of division with his irresponsible and racially coded language.

- Rachel Dolezal, a former NAACP chapter president, caused much of the nation, particularly Black America, to gawk with disbelief once it was discovered that she was a biological White woman who passed herself off as Black for reasons that no one could quite understand. She had her supporters, many more detractors, and dominated the news for several days.

- Dylann Roof. Consumed by fear, personal insecurities and racial hatred, a 21-year-old White supremacist, Dylann Roof, betrayed the trust of bible study members at the Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina, as he opened fire on them, killing nine parishioners. This horrific incident became known as the Charleston massacre. This senseless tragedy resulted in intense debates about the Confederate flag and culminated in the removal of the flag from the South Carolina State House.

- Black Lives Matter protesters made their cause known as they disrupted the rallies of presidential candidates such as Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders, Hillary Clinton, Jeb Bush and Donald Trump. With their bold, brash, fierce and no-apologies-style determination to shed light on the ongoing police violence that confronts far too many Black individuals and communities, the movement managed to become a key player in the 2016 presidential campaign.

- Jonathan Butler, a 25-year-old University of Missouri graduate student, and the Mizzou football team, were critical factors in the ultimate decision of former University of Missouri President Timothy Wolfe and university Chancellor R. Bowen Loftin to resign from their posts. The campus had been roiled by protests from many Black students—bolstered by Butler’s hunger strike and the team’s planned boycott of games—who argued that racism on the campus was a major problem. Similar protests were staged at Yale, Princeton, Vanderbilt and other institutions.

- Sexual Assault and Harassment of Women across ages, from college campuses to high-level corporations. College athletes sexually violating women, high-level and powerful executives disrespecting and sexually abusing female colleagues and/or subordinates. Situations where women were being dismissed by male co-workers as lacking ambition or the capability to advance to senior-level positions.

- Numerous Black and Some Hispanic Citizens lose their lives at the hands of law enforcement. From Tamir Rice, Eric Garner, Michael Brown, Rekia Boyd, Tanisha Anderson, Laquan McDonald, Freddie Gray, Alton Sterling, Philando Castile, Korryn Gaines, Sandra Bland, to many others. In the case of the 12-year-old Rice, he was shot by a police officer for having a toy gun in his pocket. Sandra Bland was found dead in her cell in Texas under mysterious circumstances. Eric Garner was choked to death by a police officer. Laquan McDonald was shot 17 times by a Chicago police officer. Freddie Gray was placed in the back of a police van, tied up as his spinal cord was fractured. In each of these cases, no one was indicted or held accountable for these deaths. A Texas grand jury refused to prosecute the officer in the Bland case, but the same officer was eventually indicted for perjury.

For many of us, our viewpoints on race largely have been formed by our personal experiences. In a nation that has been less than equitable to people of color—in particular, Black Americans—it is justifiable that many Black Americans are more inclined to believe that race is an intractable factor in our society that has an impervious grip on all people regardless of race, either as perpetrators or oppressors. Many of us have stories of parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins, siblings—ourselves for that matter—who have been the recipients of racism’s often poisonous venom. On the contrary, many Whites, particularly White men, are in positions where the specter of racial prejudice has little, if any, effect on their lives. Indeed, for many, institutional and structural racism is a vice against which they are largely if not totally immune.

As evidence of the fractured racial climate, individual polls from Gallup, New York Times, Washington Post, ABC, CBS and CNN have found that more than 60% of American adults believe that race relations were at their worst in more than two decades. The report showed that large majorities of Blacks and Whites, as well as Americans across all race and ethnic groups, characterized race relations as “bad.” Moreover, each poll conducted provided specific detail on the vast divide of opinion between different races on topics ranging from politics, economics, law enforcement, etc. The election of the nation’s first Black president notwithstanding, race is still the unruly, rambunctious elephant running wildly through the room. The feeling among many people across racial lines, particularly people of African descent, is that Black America is under unrelenting physical, mental and emotional siege.

Race is just one of several issues to emerge front and center in the current climate. Homophobia and sexism has managed to rear their ugly heads as well. While gay and lesbian Americans have made numerous strides—as evidenced by the fact that in 2015 gay marriage became the law of the land as the Supreme Court ruled in favor of its passage—the LGBTQ community nonetheless has dealt with an ongoing level of both subtle and overt hostility and, in some cases, outright wanton violence. The gruesome, horrific massacre of more than 50 gay and lesbian patrons at an Orlando, Florida, nightclub in June 2015 shocked and outraged much of the nation. The fact that the majority of victims were young Latinos and Latinas prompted many observers to consider whether race also played a factor in such a vile act of callousness.

Violence and harassment against women has been an ongoing vice. Over the past few years, we have seen such behavior up close as such incidents have been magnified and brought to light by around the clock media cycle, as well as more aggressive responses by a growing number of women who have decided to challenge such disrespectful and unprofessional behavior. Incidents that at one time may have been covered up, dismissed or treated in a hush hush manner by powerful individuals intent on preserving the status quo are frequently being exposed for others to see and critique. Such resistance to long-standing oppression is being challenged by aggressive activism, fostering across group alliances, conscientious literature, feminist theory, grassroots organizing, social media and other avenues.

The following essays by Elwood Watson, Deborah J. Cohan and Kathleen J. Fitzgerald aggressively and deftly tackle such issues.

1

The Fires of Racial Discontent Are Still Burning! Intensely!

It has been more than half a century since the late, mid-twentieth century black intellectual renaissance author and cultural critic, James Baldwin, wrote his classic, The Fire Next Time (Baldwin, 1963). Baldwin’s work was riveting for its time. His spellbinding narrative examined the disturbing and vehement misunderstanding between blacks (then Negroes) and whites in regards to racial injustice of the era. His book became a catalyst for many progressive Americans of all racial groups in that it prompted them into action and provided a passionate and eloquent voice for the modern Civil Rights Movement. The book became a national bestseller and further catapulted him into the premier sphere of the American intellectual elite of all races. Today, as we move further into the twenty-first century, his prophetic message rings all too chillingly true.

It is a disappointing reality that many of the indignities (racial and otherwise), as well as differences in perceptions regarding the history and treatment of black Americans ominously discussed during the 1960s, still apply today. This stark divide was evidenced in a poll conducted by CBS News in July 2015 that indicated 62 percent of all Americans (for blacks the percentage was 68) believed that tensions in race relations were the highest they had been in 20 years (Sack and Thee-Brenan, 2015). A similar poll taken in March of the same year by the Pew Research Center revealed similar attitudes (Pew Research Center, 2015). It should come as little surprise that a disproportionate number of black Americans have always been more inclined to harbor more skeptical views on racial progress. History has given people of African descent good reason to embrace such cautionary views.

The circumstances of the past few years have certainly given any racially progressive person cause for pause: the attack on voting rights by many Southern states (Berman, 2015); the sinister targeting of many low-income and working-class black home buyers by predatory lenders in the housing and financial industry (Loftin, 2010); the shocking initial indifference by many federal agencies, as well as the Bush administration reaction, to the devastating impact that Hurricane Katrina had on its disproportionately black population in New Orleans in 2005 (Lavelle, 2006). We saw hope and despair on the faces of the city’s thousands of impoverished black men, women, children and elderly that deeply demonstrated the racial and economic disenfranchisement rampant in the city. We have been witness to the obscenely horrendous treatment and disproportionate sentencing of black people (especially black men) in the criminal justice system (Alexander, 2010); the intense level of systematic and structural racism in our culture as applicants with black-sounding names are more likely to be discriminated against by potential employers than those with more “traditional” white-identified names (Bertrand and Mullainathan, 2003); massive defiance among many white radicals vehemently and defiantly supporting the Confederate flag (Agiesta, 2015); and the dilemma facing black college graduates as they are more than twice as likely to be unemployed as their white cohorts. The rise of the alternative right (Alt-Right) movement (a more sophisticated name for White Supremacists) is due to politically far right, mostly white male leaders such as Jared Taylor, Richard Spencer, Steven Bannon, former editor of the far right wing racist website Brietbart.com, obsessive online and shamelessly self-promoting blogger Milo Yiannopoulos, David Cole and Nathan Damigo, to name a few. These men and others like them promote and espouse an unprecedented level of callousness and bigotry toward immigration, multiculturalism, integration, etc., under sophisticated rhetoric and terms such as “freedom of association” (read segregation), American exceptionalism, race realism and other related code word terms. Their rhetoric is a quagmire of racism, sexism, isolationism and xenophobia (Weigel, 2016). These are just a few examples of the current fractured racial climate (Jones and Schmitt, 2014).

The callous and blatantly disrespectful treatment of the nation’s first black president, Barack Obama, by his detractors is another major example of the current poisoned atmosphere (Capehart, 2015). For many black Americans, Obama’s mistreatment was taken personally. They observe this blatant mistreatment of the president as a personal attack on themselves and the black population in general (Facebook, 2015). The gullible assumption that America had become a post-racial society (if there can ever be such a thing as “post-racial”) upon the election of President Obama was a radically misguided illusion. As a black college academic, I have had the privilege to converse over the past few years with fellow educated black and non-black professionals, some friends and other acquaintances. I have also investigated further, interacting through social media. I can personally attest that there currently exists an unmistakable level of paranoia, anger, in some cases fear, and most certainly resentment, to the current volatile situation that has gripped the nation. The temperature is hot and the climate has become dangerously unpredictable.

When premier black intellectual and renaissance man of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century W.E.B. DuBois argued that “the problem of the twentieth century will be the problem of the color line” (DuBois, 1903, p. 221), he was right on target. One can only wonder if he had any idea that this issue would be at the forefront of American society more than century later. Any historically astute individual can observe the fact that the issue of race has permeated America since its inception. Racial conflict has firmly etched itself in the fabric of the nation. It is as old as the nation’s soil itself. The undeniable fact is that there are many avenues in American society where racism flourishes. Moreover, to any honest critic, it is undeniable that black Americans have all too often borne the brunt of racial hostility and conflict over time. There are a number of intense and detailed reasons for this conflict. A combination of legal, media and social factors have contributed to this situation.

The Ongoing Problem of White Denial

Even during the days when the nation was legally racially segregated—in the era of black and white water fountains, Jim Crow laws, legally segregated schools and other public facilities that were the law of the land before the passage of monumental legislation such as the Civil Rights Bill of 1964 (1964) and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (1965)—a disproportionate segment of white Americans believed that racial equality was a reality in America. In a 1962 Gallup poll, 85 percent of whites polled believed that black children had the same opportunities as white children to receive a quality education in their communities (Newsweek/Gallup, 1962). By the decade’s end, 44 percent of whites believed that blacks had a better chance than they did to get a job with good pay as opposed to 17 percent who believed blacks had a worse chance than whites (National Opinion Survey, 1969). Unfortunately reality erred on the side of the 17 percent. The fact is that many whites have had a long and storied tradition of not knowing this history (Wise, 2014). There has been an inability on the part of whites to hear black reality. In some cases, it is the outright refusal to acknowledge such racial, economic and other related disparities. We have seen such denial manifest itself in the often hostile commentary that graces the comment sections, Twitter feeds and Facebook pages of many whites (not all) who refuse to accept the fact that maybe, just maybe, they are in the dark about the many stark realities that face a disproportionate segment of the black populace in our nation. It just might be a goo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I There is No Time for Despair: (Re)Working the Racial Order

- Part II The Space of Trauma: Violence to the Psyche, Body, and Home

- Part III Media Fallacies: Stereotypes and Other Obliterations of Black Realities

- Part IV Stone Walls: The Invisible Hand of Institutional Racism

- Contributor Biographies

- Index