![]()

1

Judgment Data in Linguistic Research

Linguistic intuitions became the royal way into an understanding of the competence which underlies all linguistic performance.

( Levelt, van Gent, Haans, & Meijers, 1977, p. 88)

1.1. Introduction

Understanding what is within the confines of a grammar of a language and what is outside the grammar of a language is central to understanding the limits of human language. Householder (1973) reminds us that this concept is not new. As early as the second century of the common era, the Greek grammarian Apollonius Dyscolus conducted linguistic analysis by analyzing sentences as grammatical or ungrammatical. However, the question remains: how do we know when something is grammatical or ungrammatical beyond the spoken and/or written data provided by native speakers of a language? With a focus on second language research, this book deals with one prominent way of determining what is part of one’s knowledge of language, namely, individuals’ judgments of what is and what is not acceptable in any given language.

Simply put, judgment tasks require that an individual judge whether a sentence is acceptable or not. The most common way of conducting a judgment task is to present a sentence and ask whether that sentence is a possible sentence in the language being asked about. As will become clear in this book, there are many variations on this theme and many controversies surrounding the methodology.

Despite the fact that judgment tasks have been central to the linguistic scene since the early days of generative grammar, their use has been the subject of numerous discussions relating to underlying philosophical issues, as well as more practical issues such as concerns about reliability, construct validity, appropriate participants, intervening factors (such as processing limitations and working memory), design, and research robustness, among others. In this book, we intend to demystify the use of judgment tasks and to present background information about their role in furthering our understanding of native and second language grammars, as well as their role in elucidating issues surrounding the learning of second languages. A central goal of this book is to describe ways to design and implement studies using judgment data and to acquaint the reader with appropriate ways to interpret results from studies that utilize such data.

1.2. Judgment Data in Linguistics

The use of judgment data in linguistics has a long history. Early research rejected the use of anything other than production data (cf. Bloomfield, 1935). Bloomfield’s arguments about linguistics as science included nonreliance on internal mental states, as they could not be verified scientifically. However, the role of judgments in linguistic work took a turn with the writings of Chomsky (1957, 1965). As Levelt et al. (1977) note, “The concept of grammaticality is a crucial one in generative linguistics since Chomsky (1957) chose it to be the very basis for defining a natural language” (p. 87). Chomsky (1965) argues early on for the importance of introspective reports when he observes that “the actual data of linguistic performance will provide much evidence for determining the correctness of hypotheses about underlying linguistic structure, along with introspective reports (by the native speaker, or the linguist who has learned the language)” (p. 18).

In Chomsky (1957), we see indirect reference to intuitions, when he states

one way to test the adequacy of a grammar proposed for L is to determine whether or not the sequences that it generates are actually grammatical, i.e., acceptable to a native speaker… . For the purposes of this discussion, however, suppose that we assume intuitive knowledge of the grammatical sentences of English.

(p. 13)

He also recognizes that using intuitional data may not be ideal:

It is unfortunately the case that no adequate formalizable techniques are known for obtaining reliable information concerning the facts of linguistic structure… . There are … very few reliable experimental or data-processing procedures for obtaining significant information concerning the linguistic intuition of the native speaker.

(Chomsky, 1965, p. 19)

However, the inability to gather reliable data should not be an impediment: “Even though few reliable operational procedures have been developed, the theoretical (that is, grammatical) investigation of the knowledge of the native speaker can proceed perfectly well” (Chomsky, 1965, p. 19).

Quite clearly, Chomsky's views are in direct opposition to earlier work by Bloomfield, whose statements expressed the notion that intuitional data should be removed from the realm of scientific investigation. Chomsky dismisses this challenge:

One may ask whether the necessity for present-day linguistics to give such priority to introspective evidence and to the linguistic intuition of the native speaker excludes it from the domain of science. The answer to this essentially terminological question seems to have no bearing at all on any serious issue.

(Chomsky, 1965, p. 20)

1.2.1. Terminology and Underlying Constructs: Grammaticality and Acceptability

Numerous terms referring to intuitional data are bandied about in the literature, and unfortunately, they are often used interchangeably even though they reflect different constructs. Primary among these terms are grammaticality and acceptability, which have different theoretical implications. We begin with Chomsky's (1965) own words about the terms acceptability and grammaticality. Many issues are incorporated in these terms, including the important difference between them and the fact that acceptability may be gradient.

Let us use the term “acceptable” to refer to utterances that are perfectly natural and immediately comprehensible without paper-and-pencil analysis, and in no way bizarre or outlandish. Obviously, acceptability will be a matter of degree, along various dimensions… . The more acceptable sentences are those that are more likely to be produced, more easily understood, less clumsy, and in some sense more natural. The unacceptable sentence one would tend to avoid and replace by more acceptable variants, wherever possible, in actual discourse.

The notion “acceptable” is not to be confused with “grammatical.” Acceptability is a concept that belongs to the study of performance, whereas grammaticalness belongs to the study of competences… . Like acceptability, grammaticalness is, no doubt, a matter of degree … but the scales of grammaticalness and acceptability do not coincide. Grammaticalness is only one of many factors that interact to determine acceptability. Correspondingly, although one might propose various operational tests for acceptability, it is unlikely that a necessary and sufficient operational criterion might be invented for the much more abstract and far more important notion of grammaticalness. The unacceptable grammatical sentences often cannot be used, for reasons having to do not with grammar, but rather with memory limitations, intonational and stylistic factors, “iconic” elements of discourse.

(pp. 10–11)

Thus, grammaticality is an abstract notion and cannot be observed or tested directly. A judgment of acceptability, on the other hand, is an act of performance, and judgment tests of the kind used in linguistics as well as second language research are subject to the same needs for experimental rigor as any other experimental task. The term grammaticality judgment is, therefore, misleading in that there is no test of grammaticality. What there is, instead, is a test of acceptability from which one infers grammaticality. Put differently, researchers use one (acceptability) to infer the other (grammaticality).

However, in the linguistics literature as well as the second language literature, these two terms are often used without a careful consideration of their differences. This is the case even for those who, as Myers (2009a) notes, “should know better” (p. 412). For instance, Schütze succumbs to this temptation in his classic 1996 book on this topic. “Perhaps more accurate terms for grammaticality judgments would be grammaticality sensations and linguistic reactions. Nonetheless, for the sake of familiarity I shall continue using traditional terminology, on the understanding that it must not be taken literally” (p. 52). Nearly 20 years after Schütze’s important book on the topic, Schütze and Sprouse (2013) acknowledge the inappropriateness of the term grammaticality judgment:

Speakers’ reactions to sentences have traditionally been referred to as grammaticality judgments, but this term is misleading. Since a grammar is a mental construct not accessible to conscious awareness, speakers cannot have any impressions about the status of a sentence with respect to that grammar; rather, in Chomsky's (1965) terms, one should say their reactions concern acceptability, that is, the extent to which the sentence sounds “good” or “bad” to them. Acceptability judgments (as we refer to them henceforth) involve explicitly asking speakers to “judge” (i.e. report their spontaneous reaction concerning) whether a particular string of words is a possible utterance of their language, with an intended interpretation either implied or explicitly stated.

(pp. 27–28)

Similarly, Ionin and Zyzik (2014), citing work by Cowart (1997), opt for the term acceptability judgment task in their review article, even though many of the studies they discuss use the term grammaticality judgment task.

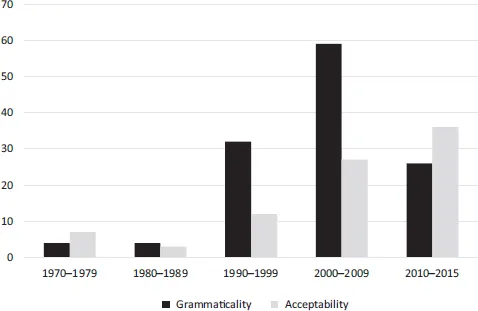

Myers (2009a) presented data based on a survey from Linguistics and Language Behavior Abstracts (LLBA) of linguistic studies mentioning grammaticality or acceptability judgments over a period from 1973 to 2007. The search input was “syntactic judgment experiments and grammaticality” and “syntactic judgment experiments and acceptability.” It is interesting to note the preponderance of the term grammaticality judgment particularly in the early years, although in more recent studies, there appears to be a switch to the more appropriate term acceptability judgment. In Figure 1.1, we present an expansion of those data to cover the period of 1972–2015. In Chapter 2, we present a comparable chart for second language research.

What do acceptability judgments reflect? Schütze and Sprouse (2013) describe acceptability judgments as perceptions of acceptability (p. 28). They point out that they are “not intrinsically less informative than, say, reaction time measures—in fact, many linguists would argue that they are more informative for the purposes of investigating the grammatical system” (p. 28). In other words, they are a useful tool for some purposes (namely understanding the grammatical system of a language), although they may be less useful for others.

We have struggled with which term to use in this book, very much wanting to use the theoretically correct term acceptability judgment, but also wishing to reflect reality in the use of these terms. We finally decided to use the term acceptability judgments throughout this book. We came to this decision in part to be theoretically consistent and in part as a way of ensuring that the field of L2 research as a whole adopts appropriate terminological usage and in so doing has a deeper understanding of the construct of judgment data. We also frequently resort to the phrase judgment task or judgment data to reflect a more encompassing view of types of judgment tasks.

Figure 1.1 Syntactic judgment experiments, 1972–2015 (Linguistics)

1.2.2. Usefulness of Judgment Data

Despite the fact that opinions on acceptability judgments are often strong, and sometimes strongly negative (see Schütze, 1996; Marantz, 2005; Myers, 2009a, 2009b; Cowart, 1997), they remain a common method for data elicitation in both linguistics and second language research. Sprouse, Schütze, and Almeida (2013), in a survey of articles that appeared in Linguistic Inquiry from 2001–2010, estimate that data from approximately 77% of those articles came from some form of acceptability judgment task. Why are these data needed? We will deal with this topic in greater detail when we turn to discussions of second language data, but at this point we refer to early uses of judgment data.

In general, within the field of linguistics, judgment data collection has been informal. This has been the case where linguists are conducting field work in an attempt to document the grammar of an unknown language, or where they use their own intuitions about possible and impossible sentences in a language to make particular theoretical claims, or when they use the “Hey Sally” method, where a colleague down the hall is called upon for a judgment (Ferreira, 2005, p. 372). In linguistics, fieldwork has occupied an important place, particularly in documenting languages where there may be little written information. For example, consider the situation when a linguist is interested in understanding the grammar of a language that has no written documentation. One way of determining the grammar of that language is to transcribe all of the spoken data over a period of time; this would be not only time-consuming but also inefficient. Of course, in today’s research world, corpora can give a wide range of sentences and utterances, but there are languages where corpora are not available or where they are limited. And, even where corpora are readily available, one is often left with the question of why x has not been heard. Is it because of happenstance, or is it because x is truly impossible in that language? It is in this sense that written or spoken data are insufficient; they simply do not capture the full range of grammatical sentences, and they provide insufficient information about what is outside the grammar of a language. The alternative is to probe the acceptability (or potential lack thereof) of certain possible sentences, attempting to determine whether they are or are not part of the possible sentences of that language. To do so, one typically asks native speakers of a language for their judgments about certain sentences.

Using judgment data allows linguists to “peel off” unwanted data, such as slips of the tongue that have gone uncorrected in spoken discourse, for example, when someone says He wanted to know if she teached yesterday. The speaker perhaps realized right away that he wanted to know if she taught yesterday was what he should have said, but in order to keep the flow of the conversation going, or for any number of reasons, the speaker does not make the change. If someone were doing field work on this “exotic” language, the conclusion would be that the first sentence was acceptable in English.

1.2.3. Reliability

A common informal use of judgment data has been the “ivory tower” use, wher...