![]()

Introduction

Pami Aalto and Kirsten Westphal

Oil is such a vital commodity for western Europe that any evidence which suggests some uncertainty or threat over its continuing supply will obviously be investigated very carefully. And when a threat looks real enough, and seems to be unavoidable, every country in Europe will naturally start examining its future energy options – just in case. Above all, answers to a lot of difficult questions will be needed.1

Europe Threatened by Energy Problems

The vitality of oil for European countries that Gordon Goodman notes in the quote above has not really changed much since he originally put forth the remark in 1981. Oil simply continues to be vital. But alongside oil there are increasing concerns for the supply of natural gas, as well as for other forms of energy. This means that today, we are speaking of a wide array of questions pertaining to European energy policy. Some of these questions are evident in the energy related problems and crises that have been witnessed during the new millennium.

The considerable oil price hikes since 2001–2 reproduced the European and global concerns for oil prices and supplies that arose with the 1970s oil crises. This time the price hikes were a consequence of several factors: the politicized struggle over the control of the Yukos oil giant in Russia during 2003–5, political unrest in oil producers Nigeria and Venezuela, unusually potent storms disrupting oil drilling and production along the US coast in 2005, and perhaps most importantly, the continuation of the US led war in oil rich Iraq since 2003. Oil prices had already been climbing for a few years from their lows of only 10–15 US dollars a barrel in 1998, but these events inched prices at over 70 US dollars in summer 2006.

At the turn of 2005 and 2006, the vital gas deliveries to the European Union (EU) from Russia, also for a while seemed to be endangered. Around 78 per cent of the gas deliveries to EU territory go through pipelines crossing Ukraine.2 The state-dominated Russian gas giant Gazprom and Ukraine were wrangling over gas prices for Russia’s deliveries to the country, and transit fees for Russian gas on its way to the wider European markets. For a few days Gazprom’s customers in western and central Europe reported reduced pressure levels in their gas pipes, sparking the question of the sufficiency of gas reserves, and, ultimately, alternative sources and supply routes.

Electricity supply blackouts emerged in the beginning of the new millennium in locations ranging from California across the Atlantic to Finland in northern Europe, Germany and Russia, due to failures in power supply line systems, dry summer and the consequent reduction in hydropower generated electricity supplies, and heavy snowfall in winter-time. At the same time electricity prices were climbing for instance in the Nordic electricity market Nordpool from 30 euros per megawatt in 2005 to over 50 euros in early 2006. Nuclear energy, which for years had looked politically a too sensitive mode of energy production after the explosion of the Chernobyl reactor in the then Soviet Ukraine in 1986, became a catchword for European energy policy makers again regardless of long-standing popular resistance to it and environmental concerns of the safety of storing nuclear waste.

In short, in the new millennium, energy issues have re-entered the global, and by implication, European policy agenda, and look set to stay there. However, two and half decades after Goodman’s remarks on oil shortages in Western Europe, European countries are situated in an entirely different context in which to respond to policy making problems. This follows from the emergence of the EU as Europe’s main economic integration machine and an all-European political process that has in many senses rendered Goodman’s term ‘western European countries’ politically incorrect. Efforts of responding to energy policy concerns at the EU level and in that way building a European energy policy were evident for example during Austria’s EU presidency in the first half of 2006, when an Energy Community secretariat was established in Vienna, seeking to create a joint energy market between the Union and the Balkans. The following Finnish presidency also took up energy as a key item on its agenda, as did Germany in spring 2007. But regardless of this infiltration of the agenda of EU presidencies by energy issues, it is the contention of this volume that most likely, we have not yet seen the real peak of European energy debates.

What we have seen in Europe during the new millennium, is increasing awareness of the centrality of energy for sustaining economic, political and social life, as well as awareness of its scarcity. This is taking place in a situation where none of the environmental concerns related to energy production and transportation have disappeared, but rather have become amplified with global warming associated with the use of hydrocarbons like oil, natural gas and coal, and the spectre of further oil transportation catastrophes in the seas after events such as the large-scale oil spills from the wreckage of the Prestige tanker in the Spanish coast in November 2002. Moreover, the EU has been caught as still struggling to establish itself if not a leading, then at least a coordinating position at the face of its western, eastern, northern and southern member states often in the first place looking to secure their own supplies by bilateral agreements with energy producers. We suggest in this volume that greater unity is needed in order to solve what essentially are shared energy problems resulting from the unequal distribution of energy resources across the wider European area, and hence, interdependence between producers and consumers in the energy market. This can effectively be read as a call for a pan-European energy policy3 geared at avoiding the problem of the commons and promoting collectively good solutions.

The Challenge of the EU–Russia Energy Relations

A central policy axis regarding our call for a pan-European energy policy is the EU–Russia energy relationship. In October 2000 the EU–Russia energy dialogue was launched to develop it further. In this volume we will focus on its implications for dealing with energy policy problems in Europe and the wider pan-European area.

What we so far know about the EU–Russia energy dialogue comes mostly in the form of empirically informative articles and reports with a descriptive approach, often coupled with a policy analytical ambition. One approach concentrates on EU–Russia energy diplomacy, and discusses how it highlights the problems and prospects of economic integration in the Eurasian continent whilst simultaneously giving some new political impetus for EU–Russia relations in the political sphere.4Geopolitics and energy security approaches situate the EU–Russia energy dialogue into the context of global geopolitics, interstate and interregional competition, and sometimes raise the spectre of proliferating resource conflicts and even wars.5 In some cases the geopolitical approach is linked to the widespread research on energy economics and trade.6 Energy diplomacy, geopolitics and energy economics and trade are also approaches that characterise energy policy research on the whole. Within this wider context, a further commonplace approach focuses on energy and the environment.7

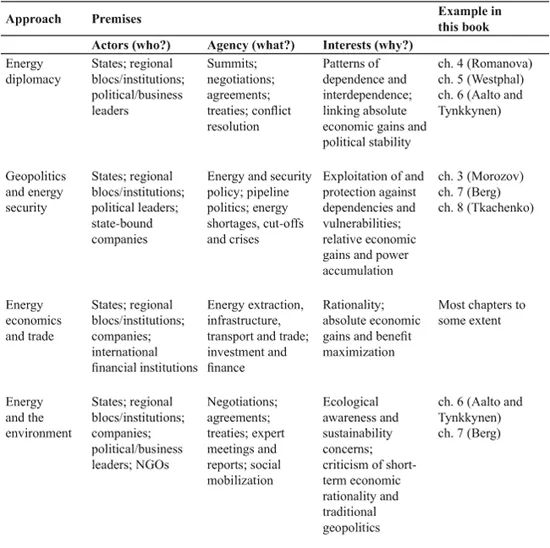

We think that energy diplomacy, geopolitical and energy economics approaches have an important place in the field, and in this book, we make conscious overtures towards these research directions. But the first instance where we wish to look for new directions is to delve deeper into the wider ramifications of energy issues as witnessed in the EU–Russia energy dialogue. In this case, these pertain not only to how the dialogue spills over from economic and technical issues to the more explicitly political and often security political realms, as well as to the environmental sector. At issue are also questions on what the EU’s and Russia’s activities in this sphere tell us about the role of energy in the past, present and future of European integration; and what role energy plays in Russia’s economic and political transformation prospects. By opening this line of enquiry that can be called the political sociology of energy, we trust to make some new openings into the policy debates on the merits and shortcomings of the energy dialogue, and outline some new ideas for its further development. The second instance where we will probe some new terrain is by covering not only the EU and Russia as monolithically understood entities, but also selected EU member states, various bureaucratic actors within them, and their links with energy companies and other interest groups. This approach can be called the bureaucratic politics of energy. Towards the end of the book we will open up a further perspective into the diversity of actors and their mutual relations by several case studies on the northern European regional interface of the energy dialogue, including regional actors in Russia. The regional politics of energy is the third instance where we wish to open up some new perspectives (Table 1.1).

We suggest that each approach has its own premises with regard to what the main actors are, what they do and how, and why they do so. Whilst the approaches can in this manner be analytically separated, in individual research efforts we frequently derive from several approaches due to the numerous issue linkages and multifaceted nature of energy policy in general (Table 1.1). Before proceeding to what we will argue in the individual contributions by making use of these approaches, we will first probe in more detail into what we mean by our central concerns of ‘European energy policy’ and ‘pan-European energy policy’.

Table 1.1 Approaches to energy policy

Questions of European Energy Policy

This volume’s aim of contributing to European energy debates necessarily raises the wider question of the extent to which there today is a European energy policy; or preferably, as we would rather frame it, the extent to which there is, or should be, a pan -European energy policy. Answers to these questions naturally depend on what is meant by the term policy. Deriving from James Anderson, Marvin Soroos defines policy as:

… a purposeful course of action designed and implemented with the objective of shaping future outcomes in ways that will be more desirable than would otherwise be expected. Discrete actions, in and of themselves, are normally not considered policies. On the contrary, a policy establishes criteria for deciding on an entire series of actions.8

Another way of putting this would be to say that a policy requires a degree of direction, purpose and stability of politics in a given realm such as energy.9 Of course, this definition of the term policy does not imply the presence of a monolithic policy shaper and implementing body. In practice what we call policies are often formed in murky conditions defined by bureaucratic struggles, mutually conflicting problem definitions and internal contradictions as suggested by the bureaucratic politics approach (Table 1.1).10 Added to this is the environment where policies need to be created, often characterized by uncertainty, complexity and conflicting voices among stakeholders and other groups affected by the policy.11

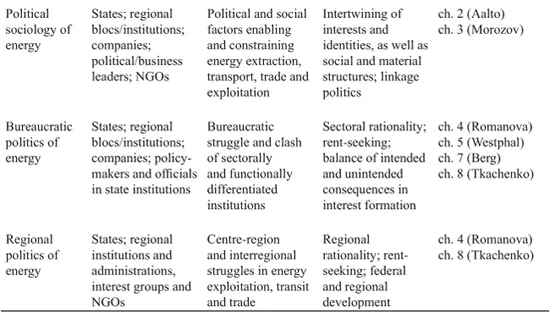

There definitely is a relatively long-standing aim of building the required direction and purpose amounting to thus understood ‘policy’ that would provide for collectively good outcomes in European energy politics. The main source of this drive is the process of European integration, despite of the fact that the results attained in the energy sphere since the end of the Cold War have not been as impressive as many have wished, and as has been seen in many other spheres of European integration. But apart from the problems of internal EU integration and the level of EU regulation, the EU needs to pay attention to its relations with its most important energy suppliers, first and foremost Russia, followed by Norway, Algeria and Saudi Arabia (Table 1.2). Another issue the Union needs to keep on the table comprises important energy transit countries in the EU–Russian borderlands, most notably Belarus and Ukraine, whilst also paying attention to transit issues within its own territory.

In other words, when speaking of European energy policy one evidently encounters the issue of management of external energy supplies to the EU area. This is why we prefer to treat questions of European energy policy as only raising new questions of the possibility of a pan-European energy policy. This naturally is quite a different challenge from devising a national or governmental policy within a member state. It is also different from a foreign policy of a given member state, i.e., something that is directed beyond its own jurisdiction. Hence, what we are faced with is perhaps best understood as a call for an energy policy within the wider European area.12

Table 1.2 EU’s external energy supplies

The creation of a wider European policy of this kind requires support from governmental policies that in Europe still represent the main source of energy policy decision-making as will be explained below. Simultaneous support is needed from the foreign policies of individual EU member states and the Union’s partners, most notably Russia, but also energy transit countries like Ukraine and Belarus. ...