- 233 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Ancient Egypt in Africa

About this book

Geographically, Egypt is clearly on the African continent, yet Ancient Egypt is routinely regarded as a non-African cultural form. The significance of Ancient Egypt for the rest of Africa is a hotly debated issue with complex ramifications. This book considers how Ancient Egypt was dislocated from Africa, drawing on a wide range of sources. It examines key issues such as the evidence for actual contacts between Egypt and other early African cultures, and how influential, or not, Egypt was on them. Some scholars argue that to its north Egypt's influence on Mediterranean civilization was downplayed by western scholarship. Further a field, on the African continent perceptions of Ancient Egypt were colored by biblical sources, emphasizing the persecution of the Israelites. An extensive selection of fresh insights are provided, several focusing on cultural interactions between Egypt and Nubia from 1000 BCE to 500 CE, developing a nuanced picture of these interactions and describing the limitations of an 'Egyptological' approach to them.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ancient Egypt in Africa by David O'Connor, Andrew Reid, David O'Connor,Andrew Reid in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction - Locating Ancient Egypt in Africa: Modern Theories, Past Realities

David O’Connor and Andrew Reid

This book moves the theme of Ancient Egypt in Africa back to where it belongs, amongst the leading challenges and opportunities facing the historians and archaeologists of Africa today. By the end of the 20th century most researchers had lost interest in a once much discussed issue – whether there had been significant interaction between Ancient Egypt and the rest of Africa – because expanding archaeological knowledge was revealing how important independent internal dynamics had been in the shaping of Africa’s varied cultures and civilizations. The chapters in this book comprise a major contribution to the intellectual history of archaeology by demonstrating in detail how earlier theories about Ancient Egypt in Africa were shaped and distorted by racial prejudice, colonial and imperial interests and now out-moded scholarly ideas. But these same chapters re-affirm that at the heart of the debate were questions of genuinely great interest and significance, which deserve to be the focus of renewed and detailed research.

To state these questions in an extreme, almost simplistic form: was Ancient Egypt to some, or even much, of Africa the source of sophisticated culture as Greece was to much of Europe, or, did Egyptian civilization incorporate fundamental African concepts markedly different from those dominant in the ancient Near East and the Mediterranean lands? In the course of this volume contributors note that there is material, both recovered and recoverable, that could well provide answers to these questions.

Re-opening the debate about Ancient Egypt in Africa in ways embracing all Africanists, instead of already committed groups of scholars such as the Afrocentrists, would also be a powerful contribution to lessening the parochialism affecting the study of early Africa. North Africa is typically studied with little reference to sub-Saharan Africa, and vice versa; within the former, Egypt is typically discussed with little reference to other North African cultures, including those with contacts extending deep into the Sahara and beyond, while within sub-Saharan Africa there is a natural tendency to focus on the demanding study of specific (often in themselves vast) regions without reference to ‘commonalities’ in thought, symbol and action that might link them together. However, as Rowlands (Chapter 4) and others show, much can be done along these lines.

This book is also an absorbing sociological study in documenting the widely ranging attitudes modern Africans have to Ancient Egypt. Interest is strong in some communities, but many African Christians and Muslims consider Ancient Egypt in very negative terms; in the Bible and the Quran “Egypt of the pharaohs” is the epitome of tyranny and obdurate paganism. In contrast, empathy with the Israelites, and similar early Near Eastern societies, can be strong for reasons well beyond religious affiliation. As Bennett (Chapter 8: 109) wryly observes, southern African peoples “recognized in the world of the early Old Testament a pastoral society more familiar and comprehensible to them than to the missionaries” who had introduced them to it in the first place!

In order to provide an introduction to the common fundamental themes that underlie the extraordinarily rich and diverse chapters comprising the book, the co-editors have divided this introduction into two. The first section explores the ideological, political and economic dimensions of the debates about Ancient Egypt in Africa carried on by European, American and African scholars and others in the 19th and 20th centuries, and shows how they were very much a part of the modern history of Africa itself. This demonstrates that the many archaeologies of Africa today are independent ones, reflecting the internal ideological and societal dynamics of the varied cultures that produced them; but that the question of contacts with and perhaps influence from Ancient Egypt is one that should remain open and challenging.

The second section focuses upon what we know about Egypt’s early contacts and influence in other parts of Africa; the potential for further research; and the extent to which one can characterize Egyptian civilization itself as in some significant way African.

It is hoped that the net effect of this introductory chapter is to persuade readers, and especially those developing careers in both Egyptology and African archaeology, anthropology and history, that the topic of Ancient Egypt in Africa provides opportunities for exciting and innovative research in the field, library and laboratory. This book (excepting biological issues) is the most comprehensive introduction to Ancient Egypt in Africa that can be provided today; 25 years from now, a book on the same topic should belong to an unbelievably richer world of both knowledge and theory.

Modern theories

In addressing the issue of Ancient Egypt in Africa this book has adopted what may seem a rather unusual structure of first tackling 19th and 20th century production of knowledge before examining the actual evidence for ancient Egyptian presence. This structure emphasizes the manner in which preconception and assumption have consistently led evidence towards particular conclusions. The concern of this book is essentially to consider the location of Ancient Egypt within broader cultural worlds. On the face of it this appears to be a rather simple issue to resolve: geographically Egypt is indisputably situated in Africa. Yet this statement immediately throws up the question, What exactly is Africa? and the logical corollary, What is African? The geographical division of the world into continents is a consequence of European geographical traditions and its fixation with categorization. Mazrui (1986) for instance presents a provocative case for redrawing the continent’s boundaries to include the Arabian peninsula. On the other hand many people, from Africa and beyond, consider Africa properly to equate with ‘black’ or sub-Saharan Africa. Not surprisingly, the definition of what is African, and what it is to be African, is still more complex. As Mudimbe (1988) has discussed at length, these are constructs which have been generated by European discourse and their definition serves the function of helping to define European worlds in contradistinction to Africa and the other continents. ‘African’ has been important in western terminology because it helps to define the opposite of ‘European’, with implicit notions of civilization and sophistication equally important to this definition. This dichotomy will be seen to have been central to the very different issues of locating Ancient Egypt and of locating Africa (see Wengrow, Chapter 9). Hence, the dominant perception of Ancient Egypt, particularly in western thought, has long been ‘in Africa, but not of Africa’. In this volume, unless otherwise stated, the term ‘African’ will be used to refer to people and objects directly from the African continent (as conventionally defined) with Egypt forming the north-eastern border.

Popular interest in Ancient Egypt’s relationship with Africa has grown since the late 1980s, and is particularly associated with the growth of Afrocentrism in the USA. This growth was in part related to the publishing of Bernal’s Black Athena (1987; and see Chapter 2), which further encouraged scholars in a number of disciplines to reconsider the academic production of knowledge as an element of western imperialism. African archaeologists, especially those working outside the north-eastern corner of the continent, have been reluctant to re-awaken interest in Ancient Egypt. This is largely because the topic, as many of the chapters of this book demonstrate, has an embarrassing history of supposition and invention which African archaeologists, rather ironically, considered to be safely buried, having been suitably dealt with in the past. In this volume re-excavation and examination of these old theories has been a difficult but ultimately enlightening experience.

Almost no archaeological evidence is currently considered to indicate ancient Egyptian contact with the rest of the African continent, excepting the Middle Nile. This rather bald statement does not mean that researchers should not try to look for shared features or ‘commonalities’ between Ancient Egypt and the rest of Africa; as this introduction and Rowlands (Chapter 4) encouragingly show, there are ways in which links may be seen. Potential connections are unlikely to be represented in material culture, but rather may be looked for in shared ideas and beliefs. Before moving on to such innovations, it is first important to discuss why the notion of ancient Egyptian contacts with the rest of Africa proved so popular in the past, despite the lack of material evidence. Ultimately, in the absence of solid evidence, ideology, or more correctly, ideologies, have served to provide the mortar which holds many of these theories together. Ideologies, it should be noted, can be positive as well as negative and Rowlands calls for the adoption of positive ideologies in generating dialogues towards meaningful contemporary African development, an outcome upon which all of the contributors can readily agree.

Locating Ancient Egypt has therefore been an exercise in ideological definition, for the most part serving less to understand Ancient Egypt itself and more to define the position of the commentator. It is in this very important context that Bernal’s and North’s contributions (Chapters 2 and 3), which may at first glance seem unrelated to the theme of Ancient Egypt in Africa, become central to the rest of the book. These chapters ably demonstrate that in defining Ancient Egypt’s cultural location in relation to European civilization, via Ancient Greece, an implicit assumption was being made regarding Ancient Egypt’s relationship with the rest of Africa. These purported relationships therefore served, and indeed in contemporary ideologies continue to serve, the purpose of constructing and ordering the world. Hence, for Europeans colonizing the African continent, locating Ancient Egypt somewhere in the Near East ordered their own relationship with Africans. Equally for Afrocentrists, locating Ancient Egypt firmly within Africa cements their belief in the significance of the African continent.

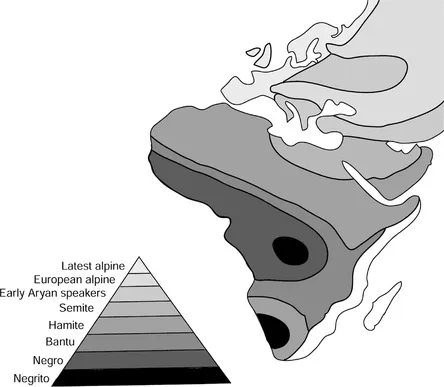

For obvious reasons, European perceptions of Ancient Egypt have had a profound influence on the African continent. As several of the chapters in this book demonstrate (Reid, Chapter 5; Folorunso, Chapter 6; Bennett, Chapter 8; Wengrow, Chapter 9), European explorers, missionaries and administrators across the length and breadth of the continent used Ancient Egypt as a counterpoint to African societies in rationalizing and legitimizing their own position of dominance. This ideological perspective was not honed in the heat of colonial expansion, but was founded on centuries of European exploitation of African slaves. Whilst Christian-based perspectives, reliant on the single human origin laid out in the Book of Genesis, saw Africans as peoples who had strayed and lost their belief in God, suffering as a direct result, secular opinions developed during the 18th century increasingly argued for separate human origins, effectively making African populations sub-human or non-human (Sanders 1969). This dichotomy helps to explain some of the differences in opinion expressed by secular and religious European observers in the late 19th century. In particular, Bennett (Chapter 8) has noted Livingstone’s persistent recognition of African intellectual capabilities. Unfortunately, such views were very much in the minority. Instead most writers held viewpoints based on the subdivision of the world’s populations into races and the social evolutionary ranking of these races into an order of sophistication. This is graphically depicted in Figure 1:1, an early 20th century manifestation of these ideas.

These ideologies helped to rationalize the European acquisition of the African continent. Europeans felt that they had a moral imperative to take control of populations who were believed to be incapable of improvement by themselves. Evidence of this was found in archaeological material across the continent. In late 19th century Africa, the vast majority of Europeans simply could not believe that Africans were capable of socio-political and cultural innovation, and drew support for this from the various archaeological manifestations they encountered on the African continent, which ‘proved’ the presence of non-African civilizations and emphasized the deterioration in society since these civilizations passed into the hands of Africans: at Great Zimbabwe, the proposed later African phase was referred to as “Bantu degeneracy” and “the Age of Decadence” (Hall 1905). These theories of past non-African civilizations were equally important in generating precedents for colonialism on the African continent, most infamously prosecuted in the case of Great Zimbabwe in what was then Rhodesia (Garlake 1982; Hall 1990, 1995; Mahachi and Ndoro 1997).

Figure 1:1 Detail of Taylor s racial stratification based on physical anthropology and environment (after Taylor 1927: 211).

It is important to understand the nature of the early contacts between Europeans and Africans and their ideological underpinnings because they frame much of the subsequent development of ideas. In these encounters Ancient Egypt was by no means the only ‘non-African’ civilization which was pictured developing colonies on the African continent, rather it was seen as one of several Mediterranean and Near Eastern societies which had left their imprint. However, the significant developments and discoveries of Egyptology, made in the 19th century, together with its direct biblical connections, served to make Ancient Egypt a popular and well-known reference point for European writers. Although archaeologists realized at an early stage that there was virtually no evidence for Ancient Egypt in the greater part of the African continent, popular ideas persevered and Ancient Egypt continued to dominate academic understanding of the archaeological record. Archaeologists interpreted their material in relation to Ancient Egypt and other non-African civilizations, their interpretations clearly dominated by Egypt’s presence. Thus, long after it was recognized that there was no evidence of direct contact with Ancient Egypt, it was still thought that most elements of innovation, such as pottery, metallurgy, domesticated plants and animals and systems of kingship, had spread up the Nile Valley (see Reid, Chapter 5 and Folorunso, Chapter 6). Diffusion was of course an extremely important explanation in late 19th and early 20th century archaeology and in broader thought. In the absence of evidence for migrations, diffusion was to many the obvious means by which Africa had been encultured. In Europe, much of the dating prior to the advent of the radiocarbon dating technique was ultimately reliant on proving claims of cultural connections to Egypt with its pharaonic chronologies. Diffusion can often become a much less precise concept than migration and evidence for diffusion can concomitantly be more ambiguous.

The generation of European historical knowledge of Africa was an important element in the construction and maintenance of European authority and power over Africa, processes which have also been noted in other parts of the world (e.g. Mudimbe 1988; Said 1978). As Zachernuk (1994: 430) puts it, “because Europeans claimed to understand the world they could claim the world”. However, as a number of the chapters in this volume demonstrate, there was not a single dominant European viewpoint, and there was also significant African development of the discourse, albeit contributions that were more often than not ignored by Europeans. Furthermore, there was not a simple European–African dichotomy, but there were European and African traditions which by no means necessarily related to conventional unitary notions of oppressor and oppressed. On the European side the difference in perspective between missionary and secular opinion on African origins has already been noted (see also Reid, Chapter 5 and Bennett, Chapter 8). A further example of discord was the intervention of the British Association for the Advancement of Science into the debate on the origins of Great Zimbabwe, sending first Randall-MacIver and then Caton-Thompson to investigate. Their research was a result of the general scepticism held in British academic circles of the southern African colonial insistence on the exotic origins of Great Zimbabwe. Both archaeologists argued for an African origin. Caton-Thompson’s public presentation in Pretoria in 1929, in which she concluded that Great Zimbabwe was quite clearly built entirely by Africans, ended in uproar; she was roundly denounced by public and academics alike. Raymond Dart, respected for his studious work on australopithecines, stormed from the room, having “delivered remarks in a tone of awe-inspiring violence” and “curiously unscientific indignation” (Cape Times, 3 August 1929, quoted by Hall 1990: 63). Despite Caton-Thompson’s conclusion, generally southern African colonists rejected the idea of the African origins of Great Zimbabwe (Hall 1995), a rejection which can still be found in Zimbabwe today (Mahachi and Ndoro 1997). These various positions indicate differences of opinion and demonstrate aspects of the gulf which rapidly developed between mother state and colony.

African responses to the notion of exotic origins varied. Whilst the contributors to this volume have generally been concerned to dismiss such ideas, African populations were clearly able to make positive use of exotic origins as an ideological tool. Within the relative confines of southern Nigerian history, Zachernuk (1994) has highlighted four separate initiatives in which the ‘Hamitic Hypothesis’ was positively used to advance group interests. Rather than colonial dupes, apeing their superiors, Zachernuk argues that these were groups pursuing their goals by using the available colonial and intellectual structures to further their own interests. For this Nigerian colonial intelligentsia, resorting to the concept of exotic origins was not only an effective means of disarming European cultural power, it was also an important means of establishing an elite history which strengthened their position as against other African actors, such as colonial chiefs.

A further example of the adoption of colonial ideologies has structured the conflict in Rwanda. The Tusi pastoralist minority, who were politically advantaged at the time of European takeover, were regarded as remnants of a Hamitic population which had migrated into the Great Lakes (see Reid 2001). Having dominated the precolonial system and with this purported link with superior migrant populations, colonial policies of indirect rule (German and Belgian) led to the isolation and non-inclusi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Series Editor's Foreword

- Contents

- Contributors

- List of Figures

- 1 Introduction - Locating Ancient Egypt in Africa: Modern Theories, Past Realities

- 2 Afrocentrism and Historical Models for the Foundation of Ancient Greece

- 3 Attributing Colour to the Ancient Egyptians: Reflections on Black Athena

- 4 The Unity of Africa

- 5 Ancient Egypt and the Source of the Nile

- 6 Views of Ancient Egypt from a West African Perspective

- 7 Cheikh Anta Diop arid Ancient Egypt in Africa

- 8 Ancient Egypt, Missionaries and Christianity in Southern Africa

- 9 Landscapes of Knowledge, Idioms of Power: The African Foundations of Ancient Egyptian Civilization Reconsidered

- 10 Ancient Egypt in the Sudanese Middle Nile: A Case of Mistaken Identity?

- 11 On the Priestly Origin of the Napatan Kings: The Adaptation, Demise and Resurrection of Ideas in Writing Nubian History

- 12 Pharaonic or Sudanic? Models for Meroitic Society and Change

- References

- Index