- 170 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Cognitive Aging and the Role of Strategy is the English Language edition of 'Vieillissement cognitif et variations stratégiques', oriiginally published in French . Lemaire is a well-respected professor and text-book author of Cognitive Psychology in France and his English language edition will have updated content on theories of cognitive aging to provide a broad view of adult development and the aging process. This title will be of interest to students of specialist psychology courses at both undergraduate and postgraduate level.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Cognitive Aging by Patrick Lemaire in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Developmental Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

COGNITIVE AGING: A BRIEF OVERVIEW

Chapter outline

The goals of the psychology of cognitive aging

Overall changes in intellectual abilities with aging

Cognitive aging and task constraints

Individual differences in cognitive aging

Conclusions

Between the ages of 20 and 60, we can lose up to 40% of our cognitive abilities. Twenty years later, we have lost a further 20%. These figures describe normal aging. That is, what we can experience if we are not suffering from neurodegenerative disease or other aging-related mental or physical health problems. Research on cognitive aging has made major progress over the last three decades. Whereas aging was once seen as an inevitable process of homogeneous cognitive decline, today we have a much more nuanced understanding. We now know that cognitive aging involves a mosaic of phenomena, of which the deterioration of certain intellectual abilities is just one facet, while the maintenance—and even the improvement—of certain other abilities is another. The general idea defended in this book is that the best way to improve our understanding of cognitive aging is to take a strategy approach. This consists of studying age-related differences and changes in strategic variations (i.e., the repertoire, distribution, execution, and selection of strategies) and using methods which are suitable for assessing these variations. Most of this book will focus on showing how this strategy perspective enhances our understanding of cognitive aging. First, this chapter presents a brief overview of the main age-related effects on human cognition (for more detailed and exhaustive presentations, see Craik & Salthouse, 2008; Lemaire & Bherer, 2005, and Salthouse, 2010b). We will then go on to see how the strategy perspective can shed light on these phenomena, as well as uncovering others which would otherwise go entirely unrecognized. The next section begins by reviewing the main goals of the psychology of cognitive aging. The section that follows presents the overall trends in how cognitive performance changes with age, before looking at how various factors modulate these trends. The fourth section discusses observed individual differences in cognitive aging, and the fifth and final section concludes this brief overview.

The goals of the psychology of cognitive aging

The overarching goal of research in the psychology of cognitive aging is to understand how our intellectual abilities change with age during adulthood. This change can result from “normal” aging (i.e., in any individual who does not suffer from dementia or any other age-related neurodegenerative pathology) or from “pathological” aging (i.e., in case of disease). Normal cognitive aging will be the focus of this book.

Researchers pursue a number of objectives in parallel in order to attain this general goal. First, they describe in detail how our cognitive performance changes with age in various domains, from the most basic levels of cognition (such as perception and pattern recognition) to its most highly integrated levels (such as reasoning and decision making). The question in this context is whether certain cognitive functions are more affected by aging than others. Among the affected functions, how much does each one decline? Do certain functions deteriorate more and earlier than others? Do the speed and range of decline vary from one function to another? What kind of involution does each function go through over time? For a given function, does performance on one task decrease more than performance on another task, which assesses a different component of that function? Are some preserved? Does change over time in different functions interact with task constraints? In other words, regardless of the domain of cognition that is studied, the task is to describe what changes (i.e., deteriorates or improves) and what remains stable across ages.

It is not always easy to draw clear conclusions on age-related changes of different functions. For a given function in a given domain (e.g., memory), often large performance differences are observed between young and older participants (e.g., in recall tasks assessing episodic memory); sometimes smaller differences are found (e.g., in episodic memory recognition tasks); and sometimes even no differences with age are observed (e.g., in implicit memory tasks). For example, in studies on implicit memory, some researchers have found no differences between young and older participants when probing implicit memory using word-fragment completion tasks, where participants are shown a group of letters and asked to add letters to this group in order to make a word (e.g., Clarys, Isingrini, & Haerty, 2000; Fay, Isingrini, & Clarys, 2005; for similar results with a motor task, see also Chauvel et al., 2012; Fleischman, Wilson, Gabrieli, Bienias, & Bennett, 2004), or an identification task where participants are shown pictures of objects and are asked to name them (e.g., Mitchell, 1989). In contrast, other researchers have found large differences between young and older participants when they have probed implicit memory using a task requiring participants to spell words aloud (e.g., Davis et al. 1990). On one task, trigram completion (i.e., participants are shown the first three letters of a word and have to complete it with the missing letters to form a word), certain studies have reported deleterious effects of age (e.g., Small, Hultsch, & Masson, 1995; Winocur, Moscovitch & Stuss, 1996), while others have reported no effects (e.g., Clarys et al., 2000; Fay et al., 2005; Nicolas, Ehrlich, & Facci, 1996).

The use of a wide range of tasks, techniques, and measures is required to produce convergent results that reveal the patterns underlying the diversity of findings. By studying differences between domains and tasks, as well as within tasks, psychologists aim at establishing the most detailed and precise possible cartography of how cognition changes with age. Their ambition is to uncover the general characteristics that distinguish cognitive functions and processes which change with aging from those that remain stable. One important general feature that characterizes age-related changes in many cognitive function is costs in processing resources. As we shall see in this book, across a wide range of cognitive domains, the more demanding in processing resources, the larger deleterious aging effects. In sum, the first objective of cognitive aging research is to as precisely and with as many details as possible determine what changes and what remains stable with aging in human cognition.

The next question is whether there are individual differences in how cognitive performance changes with aging. In other words, does aging affect everyone in the same way, or are there individuals whose performance does not decline at all with age, or individuals whose decline is less marked than others? Once these individual differences have been determined and documented with great details, the next task for psychologists is to determine what characterizes individuals who experience greater deficits with aging versus those undergoing much more successful aging. The extent of decline can be assessed both by the number of domains where deficits are observed and by the amount of decline in a given domain. Aging patterns can vary widely. An individual might experience smaller deficits in many domains, or, in contrast, very significant deficits in a smaller number of domains. Moreover, two comparable patterns of cognitive decline (in terms of magnitude and/or number of deficits) can result from different underlying realities (e.g., different cognitive mechanisms are affected). To determine the origins of these individual differences, psychologists study a wide range of variables: Cognitive (e.g., level of formal education), affective (e.g., emotional stability), and personal characteristics (e.g., intro-/extraverted personality, gender, physical health), as well as life history (e.g., profession, stress, trauma) and habits (e.g., diet, exercise, and socio-cultural activities). The study of these variables allows researchers not only to determine what characteristics underlie individual differences, but also to investigate the mechanisms that produce them. It can also yield highly general information on human cognition (e.g., what are the conditions for optimal cognitive plasticity? What conditions are needed to maintain, or even continuously develop, cognitive functioning over the lifespan? What are the limits of our cognitive capacities?).

The third objective of research on cognitive aging is to determine what mechanisms underlie observed changes (as well as stability) in cognitive performance during adulthood. Age, or the passage of time, is in no way the cause of cognitive aging. Instead, what psychologists of cognitive aging try to find out is what happens in our lives as time passes. This chain of events plays out at different levels of the cognitive system, from the molecular and cellular levels all the way up to the most integrated and functional levels of the central nervous system. Psychologists focus more on the functional and behavioral levels, although they increasingly work in close collaboration with researchers in other disciplines which study aging, such as neurosciences and biomedical sciences.

Finally, while the goal of basic research is not to produce immediate solutions to practical problems—given that the usefulness of fundamental discoveries, although very important, is often an unintentional and unpredictable result of the quest for understanding—one of the reasons to value research on aging is that it can lead to applications. There are many such applications, both in pathological aging (improved diagnosis and care for older patients, better support for care-takers) and in normal aging (to help each of us to undergo successful aging). In the case of normal aging, insofar as basic research tells us about the conditions required to age “successfully,” its discoveries offer the promise not necessarily of adding more years to life but, as a celebrated phrase puts it, of “adding more life to (years of) life.”

Overall changes in intellectual abilities with aging

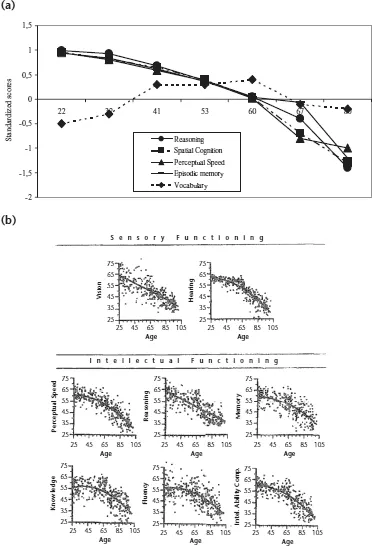

To study age-related differences in our intellectual abilities, researchers administer various tasks to young adults (between the ages of 20 and 40) and older adults (aged 65 and older). These tasks either assess overall intellectual functions or specifically target certain functions and/or processes. The overall tests include, for example, the famous IQ (intelligence quotient) tests, and offer a general assessment of intellectual abilities and how these abilities change with age. Many studies have used these types of tests and either compared the performance of young and older people (in cross-sectional designs) or else followed the same cohort of participants over many years (longitudinal designs). The results of such studies are illustrated in Figure 1.1. For example, Figure 1.1a shows data from the Seattle Longitudinal Study. These data show the performance of over 1,300 adults tested by Schaie and collaborators (Schaie, 1996) with the Primary Mental Abilities Test assessing reasoning, spatial cognition, perceptual speed, episodic memory, and vocabulary. As can be easily seen, apart from vocabulary, age leads to decreased intellectual performance. Figure 1.1b presents another example, the data from the Berlin Aging Study, in which Baltes and Lindenberger (1997) studied the sensory and intellectual functions of more than 300 participants between the ages of 20 and 103. At the sensory level, they tested visual and auditory acuity. At the intellectual level, they tested information-processing speed, reasoning, memory, knowledge, and verbal fluency. As the data in Figure 1.1b show, aging is accompanied by a steady and continuous decline in all of our sensory and cognitive abilities.

FIGURE 1.1 Changes in intellectual abilities with age: (a) standardized scores on the Primary Mental Abilities Test (following Schaie, 2005); (b) scores on different sensory and cognitive measures from the Berlin Aging Study. (Data from Baltes, P. & Lindenberger, U. (1997). Emergence of a powerful connection between sensory and cognitive functions across the adult lifespan: A new window to the study of cognitive aging. Psychology and Aging, 12, 12–21, APA, reprinted with permission.)

Note that similar patterns of change in cognitive performance with age have been observed in longitudinal and cross-sectional studies. The decline with age seems to be (artificially) smaller in longitudinal studies, due to a simple test–retest effect. That is, performing the same tests a number of times, even at intervals of some years, attenuates the decrease in performance with age (Salthouse, 2010a, 2014). As interesting, informative, and valid as these data from psychometric studies on aging are, they are also limited in some ways. The most important of these, regarding what deteriorates and what remains stable with age in human cognition, is that these data suggest that all sensory and intellectual functions (except for vocabulary and knowledge) decline with age, beginning very early and going on steadily and continuously thereafter. And yet, when researchers began to take a cognitive perspective and started to analyze cognition in terms of information-processing operations, they observed that patterns of cognitive change can vary widely according to the domains tested and the tasks used. By breaking down broad intellectual functions into basic processes, researchers arrived at a picture of aging that was much richer and more interesting than the one that had pre...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Cognitive Aging

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Cognitive Aging: A Brief Overview

- 2 Cognitive Strategies

- 3 Aging and Strategy Repertoire

- 4 Aging and Strategy Distribution

- 5 Aging and Strategy Execution

- 6 Aging and Strategy Selection

- 7 Conclusions

- References

- Author index

- Subject index