- 284 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Identities, Boundaries and Social Ties

About this book

Identities, Boundaries and Social Ties offers a distinctive, coherent account of social processes and individuals' connections to their larger social and political worlds. It is novel in demonstrating the connections between inequality and de-democratization, between identities and social inequality, and between citizenship and identities. The book treats interpersonal transactions as the basic elements of larger social processes. Tilly shows how personal interactions compound into identities, create and transform social boundaries, and accumulate into durable social ties. He also shows how individual and group dispositions result from interpersonal transactions. Resisting the focus on deliberated individual action, the book repeatedly gives attention to incremental effects, indirect effects, environmental effects, feedback, mistakes, repairs, and unanticipated consequences. Social life is complicated. But, the book shows, it becomes comprehensible once you know how to look at it.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Identities, Boundaries and Social Ties by Charles Tilly in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Introduction

Chapter 1

Ties That Bind … and Bound

LIAH GREENFELD HAS NAILED UP FIVE CHALLENGING THESES about the social sciences on the highly visible virtual doors—the websites—of Boston University. Theses 2 and 3 castigate the social sciences for taking physics as their scientific model, and for organizing disciplines around political and ideological concerns. The remaining theses read as follows:

1. Even though the human sciences were meant to study humanity, they focus on social structures, which, far from being distinctively human, are essential in the lives of all animals, hence are best addressed by biology. What separates humanity from the rest of the animal kingdom is not society or social structures, but the transmission of social order via symbolic means, i.e., culture, rather than by genes. Symbolic or cultural processes take place primarily in people’s minds. Instead of being unconscious subdisciplines of biology, the social sciences should be sciences of culture and the mind.

4. Quantification and mathematical modeling, applied to the study of social “structures,” tended to treat them as if they evolved mechanically. Mental reality, in turn—i.e., the meaning that people assign to their actions—was postulated to be a mere reflection of these structural processes, and therefore was grossly under-researched.

5. The problems of this paradigm are seen in the failure of social-scientific predictions, and the inability of social science to provide useful solutions to social problems. It is also reflected in the fact that, while sophomores in physics have left Newton far behind, the writings of Weber, Durkheim, even Plato and Aristotle, often seem more adequate than many contemporary social-scientific studies for understanding the world in which we live (Friedman 2004: 144–45; see also BU 2004).

Greenfeld’s five theses propose culturally informed phenomenology as the proper alternative to the mechanical representations that have, in her view, held back the social sciences.

In terms that will appear repeatedly through the rest of this book, Greenfeld is fostering dispositional explanations of social processes in opposition to their chief alternative: transactional explanations. (As chapter 2 declares, social theorists have historically given plenty of attention to a third alternative—explanation by reference to self-sustaining social systems—which currently attracts few supporters, and which in any case Greenfeld also rejects.) But within dispositional accounts, she is also rejecting those views of human consciousness that treat it as rationally calculating and/or closely bound to physiology. She calls for social scientists to center their attention on the pursuit of meaning by cultured minds. Thesis 4 states the point explicitly: mental reality consists of “the meaning that people assign to their actions.”

In her own research, Greenfeld follows the creed. Greenfeld’s explanations center on transformations of culturally informed consciousness. Her first book laid out a comparative history of nationalism centering on the birth and diffusion of a peculiar but potent set of beliefs (Greenfeld 1992). Her more recent Spirit of Capitalism assembles comparative histories of England, the Netherlands, France, Germany, Japan, and the United States to expand her previous claims (Greenfeld 2003). Nationalism, for Greenfeld, exists when people subject to a common political authority share consciousness of belonging to a distinctive sovereign community. In the earlier book, the timing and form of nationalism, thus defined, accounted for distinctive subsequent political orientations in England, France, Russia, Germany, and the United States.

In her more recent book, Greenfeld proposes an aggressively dispositional explanation. She argues that similar changes in consciousness caused people to overturn millennia of suspicion as they committed themselves to a belief in economic growth as desirable and natural. They did so because identification with the nation promoted a shared sense of dignity, efficacy, and relative equality among the nation’s members, hence a new willingness to undertake economic effort whose outcome depended on the efforts of distant others. Changed beliefs, according to the argument, then caused sustained economic growth to occur, country by country.

Greenfeld prudently denies that nationalism causes reorientation to economic growth wherever it occurs. She also allows that the capabilities assigned center stage in most economists’ accounts of economic growth affect how and how fast growth occurs. She accordingly distinguishes between economists’ stories of how and her—motivational—story of why. Greenfeld’s story self-consciously pits nationalism against Weber’s Protestant Ethic, while retaining Weber’s general causal logic: new cultural forms generate new forms of consciousness, which in turn shape economic activity.

Against arguments locating the conditions of economic growth in proper market mechanisms, appropriate mixes of economic resources, technological innovations, and/or disciplined, achieving cultures in the style of Max Weber’s Protestants, Greenfeld’s analysis offers something new and intriguing: a stress on identifications with communities of fate as promoters of costly collective action. (This book’s chapter 4 takes up that very issue.) Like Margaret Levi’s analysis of popular compliance with state demands, Greenfeld’s treatment of nationalism draws our attention to the crucial importance for collective enterprises of arrangements that increase the probability—or at least the perception—that others will join the common effort, and that authorities will impose public obligations more or less uniformly (Levi 1988, 1997).

For such an argument to gain credibility, nevertheless, Greenfeld’s international comparisons must show that the sequence 1) nationalism 2) belief change 3) economic growth recurred both within countries and across them. The within-country component calls for a demonstration that national consciousness did, indeed, alter whole populations’ commitments to economic activity, and that altered commitments did, indeed, fuel sustained growth. The across-country component requires earlier nationalism in England than elsewhere, absence of sustained economic growth in Tokugawa Japan, and so on. It implies that both nationalism and economic commitment eventually transformed the United States even more profoundly than its predecessors. It also necessitates brushing off objections that economic growth in the Netherlands, China, or elsewhere either preceded or caused that of England.

Fully aware of these logical requirements, Greenfeld sets up the book as a series of single-country analyses in roughly chronological order. She precedes the country-by-country reviews with a pithy introduction and follows them with a thoughtful epilogue concerning the (very mixed) future of economic growth, especially in her native Russia. Readers should therefore ask three questions of the book: Do the treatments of individual countries adequately describe their experiences with nationalism, alteration of mentalities, and economic growth? Do within-country and cross-country sequences correspond to the argument’s logical requirements? Do the proposed causal processes hold up to empirical and logical scrutiny?

On the first count, Greenfeld concentrates so heavily on ideological transformation that historically informed readers will constantly find themselves calling up unmentioned and unanswered alternative explanations. In the case of England, for example, I could not suppress thoughts about how the 16th century shift from wool to cloth production signaled England’s integration into the continental economy, especially that of the Low Countries and northern France. On the second count, the dismissal of the early-developing Netherlands, although well informed, looks like special pleading: the nonnationalist Dutch Republic, Greenfeld tells us, poses no objection to the general thesis because its economy probably contracted during the later 17th century, a contraction that disqualifies it as a case of sustained economic growth. On the third count, the dual processes by which first awareness of a shared nation spreads and then that awareness motivates economic effort remain underspecified and mysterious.

Greenfeld’s linking of economic growth to nationalism has many virtues: boldness, serious engagement with history, systematic use of national comparisons, grappling with serious problems. If my line of argument holds, however, her adoption of a dispositional account dooms the effort to failure.

Later chapters present my own view of nationalism and offer different descriptions of several countries that Greenfeld takes up, notably England and France. What matters here, however, is the claim to explain. You can’t get there from here, I argue: however finely etched, the quickening awareness of whole peoples that they belong to a sovereign nation cannot explain their country’s takeoff into economic growth. In principle, any such explanation must account for realignment among the major factors of production: capital, labor, land, and technology. It is at best implausible that parallel shifts in national consciousness caused that realignment in country after country (Kohli 2004, Mokyr 2002, Pomeranz 2000). Even if that implausible effect occurred, we would still need to know how it produced realignments of capital, labor, land, and technology. Here the how is the why.

Greenfeld’s arguments provide a helpful specification of the position against which this book rebels from beginning to end: the claim that individual and collective dispositions explain social processes. The pages that follow do not deny that individuals have consequential dispositions, or that ambient culture informs those dispositions. Nor do they endorse physics as a model for the social sciences. They make the case, however, for interpersonal transactions as the basic stuff of social processes. They show how interpersonal transactions compound into identities, create and transform social boundaries, and accumulate into durable social ties. They claim that individual and collective dispositions result from interpersonal transactions.

Resisting the focus on deliberated individual action, furthermore, this book repeatedly gives attention to incremental effects, indirect effects, environmental effects, feedback, mistakes, repairs, and unanticipated consequences. Doing so, it heeds Mustafa Emirbayer’s call for a newly relational social science (Emirbayer 1997). But it also harks back to Robert Merton’s insistence on mechanism-based explanations of social processes (Merton 1968: 43–44).

Strictly speaking, we observe transactions, not relations. Transactions between social sites transfer energy from one to another, however microscopically. From a series of transactions we infer a relation between the sites: a friendship, a rivalry, an alliance, or something else. (Without being too rigid about it, in general, I will call those connections “ties” when referring to their durable characteristics, and “relations” when talking about their dynamic interactions.) Cumulatively, such transactions create memories, shared understandings, recognizable routines, and alterations in the sites themselves. In the pages that follow, I will sometimes speak of transactional perspectives but of relational mechanisms. Most of the time, however, I will save words by lumping the two together as “relational.”

Relational mechanisms figure prominently throughout the book. Some chapters simply pit them against dispositional explanations, as in my imagined debate with Liah Greenfeld. Others place them ontologically, claiming that transactions and relations provide a firmer ground for analysis than do social systems or disposition-propelled actors. Still other discussions concentrate on the logic of explanation as such; they distinguish covering law accounts, specifications of necessary and sufficient conditions, variable-based searches for correlations, location of elements within systems, imputations of dispositions, and explanations involving mechanisms and processes (see Stinchcombe 2005). In the latter case, transactional mechanisms and processes typically combine with their environmental and cognitive counterparts.

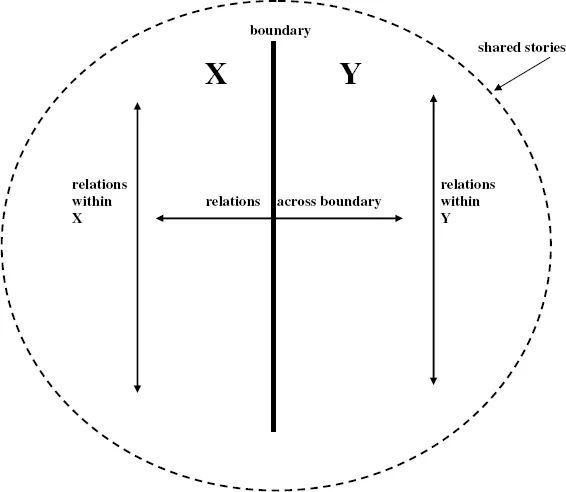

Figure 1-1 provides a sample of the reasoning you will encounter repeatedly in later chapters. Overall, it analyzes the transformation of collective identities: shared answers to the questions “Who are you?” “Who are we?” or “Who are they?” Such identities, it indicates, center on boundaries separating us from them. On either side of the boundary, people maintain relations with each other: relations within X and relations within Y. They also carry on relations across the boundary: relations linking X to Y. Finally, they create collective stories about the boundary, about relations within X and Y, and relations between X and Y. Those stories usually differ from one side of the boundary to another, and often influence each other. Together, boundary, cross-boundary relations, within-boundary relations, and stories make up collective identities. Changes in any of the elements, however they occur, affect all the others. The existence of collective identities, furthermore, shapes individual experiences, for example, by providing templates for us Croats and distinguishing us from those Serbs.

Figure 1-1. Boundaries, Ties, and Identities

Here we face an important choice, the same choice posed by Liah Greenfeld’s work. We can, like most analysts, treat identities as characteristics of individual consciousness: how you think of yourself. Or, with relational analysts, we can observe that:

• identities reside in relations with others: you-me and us-them

• strictly speaking, every individual, group, or social site has as many identities as it has relations with other individuals, groups, or social sites

• the same individuals, groups, and social sites shift from identity to identity as they shift relations

• every political process includes assertions of identity, including definitions of relevant us-them boundaries

• such assertions almost always involve claims about inequality—our superiority, our subordination, their unjust advantages, and so on

• nevertheless, profound social processes affect which identities become salient, which ones remain subordinate, and how frequently different identities come into play

• political institutions incorporate certain identities (for example, “citizen” or “woman”) and reinforce the relations on which those identities build

• struggles over and within political institutions therefore regularly involve conflicting claims over what political identities have public standing, who has rights or obligations to assert those identities, and what rights or obligations attach to any particular identity

• of course, all such processes have phenomenological components and effects, but give and take among individuals, groups, and social sites—including political contention—create the regularities in identity expression that prevail in any particular population

Identities, Boundaries, and Social Ties unpacks these arguments in detail. Parts 4 and 5 of the book (“Boundaries” and “Political Boundaries”) deal most extensively with these identity processes. But they underlie the book’s reasoning from beginning to end.

Part 2 (“Relational Mechanisms”) focuses on political processes: collective violence, democratization, and sacrifice for collective causes. Within those processes, however, it seeks out recurrent causal mechanisms that produce alterations in connections among social sites: relational mechanisms. Without denying the significance of other sorts of mechanisms—cogn...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Preface

- Introduction

- Relational Mechanisms

- Inequality

- Boundaries

- Political Boundaries

- References

- Index

- Credits

- About the Author