- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Ending Hunger Worldwide

About this book

Why does hunger persist in a world of plenty? Ending Hunger Worldwide challenges the naive notion that everyone wants hunger to end, arguing that the powerful care - but not enough to make a difference. George Kent argues that the central focus in overcoming hunger should be on building stronger communities. It is these communities which can provide mutual support to ensure that people don't go hungry. Kent demonstrates that there is not a shortage of food but of what Amartya Sen terms 'opportunities', and that developing tight-knit communities will lead to more opportunities for the hungry and undernourished. Ending Hunger Worldwide challenges dominant market-led solutions, and will be essential reading for activists, NGO workers and development students looking for a fresh perspective.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

NUTRITION PROBLEMS

Numbers and Definitions

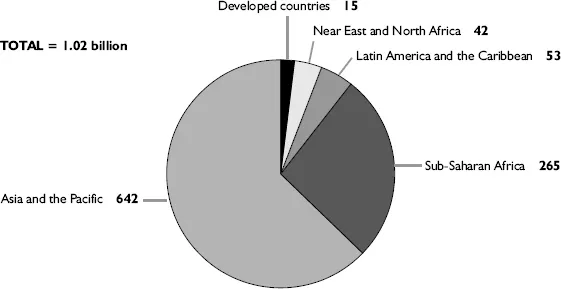

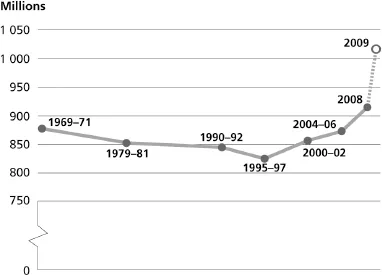

The number of undernourished people in the world has been more than 800 million for decades (FAO 2006), and in recent years it has been getting worse (see Figure 1.1). In June 2009 the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) reported, “For the first time in human history, more than one billion people are undernourished worldwide. This is about 100 million more than last year and around one-sixth of all humanity” (FAO 2009a; FAO 2009c, 4; Blas 2009a).

The number of undernourished people steadily increased beginning in the mid-1990s, spiking sharply upward during the global food price crisis of 2006–2008 and the global economic crisis that followed (see Figure 1.2).

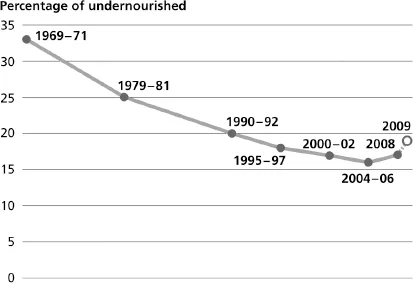

The proportion of hungry people (as distinguished from the number) went down steadily until 2004–2006, to about 17 percent of the population in developing countries (see Figure 1.3), but it started rising again after that (FAO 2009c, 11, Fig. 6).

The reasons for this pattern are not known with certainty. The long, slow decline in both the number and the proportion of hungry people undoubtedly was due largely to economic growth in many countries. The slowness of the decline might be attributed to the fact that economic growth generally tends to favor those who are already well off. The upturn early in the twenty-first century is surely linked to the weakening of the entire global economy.

Figure 1.1 Undernourishment in 2009, by region (millions)

Source: FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations) 2009c. The State oƒ Food Insecurity in the Worl. Rome: FAO. http://www.fao.org/docrep/012/i0876e/i0876e00.htm, Figure 4.

Data on the food security situation in different countries may be found at http://www.fao.org/faostat/foodsecurity/index_en.htm and also in the Technical Annexes of the FAO’s annual reports on The State of Food Insecurity in the World (FAO 2009c).

The widely accepted definition is, “Food security exists when all people, at all times, have physical, social, and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs for an active and healthy life” (FAO 2009c, 8). Its major elements are availability, access, and utilization:

Food availability in a country, region, or local area means that food is physically present because it has been grown, processed, manufactured, and/or imported.

Food access refers to the way in which different people obtain available food. Normally, food is accessed through a combination of means. This may include: home production, use of left-over stocks, purchase, barter, borrowing, sharing, gifts from relatives, and provisions by welfare systems or food aid.

Food utilization is the way in which people use food. It is dependent upon a number of interrelated factors: the quality of the food and its method of preparation, storage facilities, and the nutritional knowledge and health status of the individual consuming the food. (International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies 2007)

Figure 1.2 Number of undernourished people over time

Source: FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations) 2009c. The State of Food Insecurity in the World. Rome: FAO. http://www.fao.org/docrep/012/i0876e/i0876e00.htm, Figure 5.

Figure 1.3 Proportion of undernourished people over time

Source: FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations) 2009c. The State oƒ Food Insecurity in the World. Rome: FAO. http://www.fao.org/docrep/012/i0876e/i0876e00.htm, Figure 6.

The availability of food refers to the overall quantities and types of foods in any particular place, while accessibility refers to the ability of individuals to obtain that food. Some people may be too poor and too powerless to get the food that is available. Many famines have occurred in places where overall food supplies have been more than adequate. For example, at the end of the twentieth century India had more than 200 million malnourished people—more than any other country in the world—while at the same time the government was holding some 60 million metric tons of grains in storage (Kent 2005, 143).

Where food is available and accessible, it still may be utilized badly, perhaps through unwise choices of food items or unskilled preparation. In some cases poor utilization of the food that is obtained may be due to problems with digestion. Inadequate hygiene can lead to intestinal infections and parasites, diminishing the benefits obtained from the food that is eaten (Latham 2008). Other difficulties in processing the intake can occur, as in certain metabolic abnormalities such as celiac disease and lactose intolerance.

While availability, access, and utilization have long been recognized as key elements of food security, stability has now been added to the list (FAO 2009d, Note 1).

Food Security versus Nutrition Security

The FAO also added to its definition of food security the point that, “The nutritional dimension is integral to the concept of food security” (FAO 2009d, Note 1). This implicitly acknowledges that there is more to nutrition than just the energy (calories) that food provides.

The FAO uses the terms hunger and undernourishment interchangeably. It says, “Undernourishment exists when caloric intake is below the minimum dietary energy requirement” (FAO 2009c, 8). FAO estimates the extent of undernourishment by analyzing the supply of food and relating that to the energy needs of the population.

In a more clinical approach, the medical journal The Lancet says a good indicator of chronic undernutrition is low weight in relation to height. Using a standard formula based on weight and height, a body mass index below 18.5 is generally agreed to mean that the individual is underweight. An index of less than 16 indicates severe undernutrition (The Lancet 2009).

Although energy is important, our bodies also need protein and various vitamins, minerals, and other micronutrients. Most people obtain these nutrients from a diverse diet, but in some cases they might be obtained through various forms of food supplements. The major micronutrient deficiencies worldwide are vitamin A, iron, iodine, and by some counts, zinc. Micronutrient deficiencies are sometimes described as causing “hidden hunger” (Micronutrient Initiative 2010).

Thus we need to be concerned not only with undernutrition (too few calories), but also with malnutrition in all its forms. Malnutrition may occur when a person becomes vulnerable to deterioration in health because of problems relating to food supplies. According to the World Health Organization (WHO):

Nutrition disorders can be caused by an insufficient intake of food or of certain nutrients, by an inability of the body to absorb and use nutrients, or by overconsumption of certain foods. Examples include obesity caused by excess energy intake, anemia caused by insufficient intake of iron, and impaired sight because of inadequate intake of vitamin A.

Nutrition disorders can be particularly serious in children, since they interfere with growth and development, and may predispose to many health problems, such as infection and chronic disease. (World Health Organization 2008a)

Being overweight and, in its more extreme form, obesity, are now increasingly recognized as major problems of malnutrition. Some observers interpret this simply as a sign of overeating (“overnutrition”), but the evidence suggests that overweight really is due more to changes in the quality of the diet rather than the quantity, together with shifts toward more sedentary lifestyles. The rapid increase in overweight in recent years, among the poor as well as among the rich, is largely due to the shift to processed foods, especially highly sweetened drinks.

Many common forms of malnutrition are due to inadequate overall food intake, specific micronutrient deficiencies, and imbalances in food supply that lead to overweight. This is the food-centered perspective. The fact that other factors, apart from food, also have major effects on people’s nutrition status should be acknowledged. In the conceptual framework advanced by UNICEF, good nutrition depends not only on good food but also on good health services and good care practices (Pelletier 2002). Nutrition security can be defined as the “appropriate quantity and combination of inputs such as food, nutrition and health services, and caretaker’s time needed to ensure an active and healthy life” (Haddad, Kennedy, and Sullivan 1994). As described by the Millennium Development Project, “Chronic undernourishment is caused by a constant or recurrent lack of access to food of sufficient quality and quantity, good healthcare, and necessary caring practices” (United Nations Millennium Project 2005, 2).

FAO estimated that the number of people who are hungry (or food insecure or undernourished) as having passed the one billion mark in 2009 based on its focus on undernutrition, meaning energy (calorie) deficiency. However, malnutrition includes not only undernutrition but also micronutrient deficiencies of various kinds. Some estimates say this would add a second billion to the number of malnourished people in the world. Also, perhaps a billion are overweight, though some of these are people who also suffer from micronutrient deficiencies. If we add those whose nutrition status is poor because they do not receive the health and care services they need, the number would be still higher. Certainly a third, and perhaps as much as half, of the world’s population is malnourished to the extent that it results in some deterioration of their health.

We do not have exact figures on the number of people in the world who are seriously malnourished, but we know it is a very large number. The challenge is not simply to ensure that enough food is produced, but to ensure that everyone is well nourished. Attention needs to be given not only to overall food supplies but also to issues such as affordability, eating habits, and child feeding practices. To be well nourished, people need not only food but also appropriate health and care services. Programs of action should be designed to ensure that all people are well nourished under all conditions.

In assessing food security worldwide based on estimates of energy intake, the FAO provides a very useful service. However, we must recognize that any single measure of malnutrition assesses only one particular dimension and does not provide a comprehensive view of all concerns related to nutrition. Malnutrition takes many forms, and work on one of them (such as stunting in young children) might have little relevance to others (such as preparing for future disasters). When people propose answers to nutrition problems, it is important to find out what question they are asking.

Although the technical definitions are important and interesting, this book does not deal with the clinical aspects of malnutrition. It addresses the social forces that sustain it and the social policies that might contain it. It is concerned mainly with those aspects of malnutrition that are associated with poverty, identified here broadly as the problem of hunger.

Other Perspectives

The preceding account presents the conventional mainstream understanding of hunger worldwide. However, different ways of explaining hunger and different objectives lead to different views of what needs to be done.

In the conventional view, major categories of malnutrition exist, and large numbers of people are affected by them. Malnutrition is usually seen as resulting from deficits of some kind, such as missing nutrients or inadequate income, land, water, skills, markets, health services, or information of some kind. It follows that the task is to somehow fill in those deficiencies.

We like to say, “Give a person a fish and he eats for today, but teach a person to fish and he eats for a lifetime.” We want to teach the poor and powerless how to grow food, plan families, and become entrepreneurs and democrats. We might not notice that the fish have been taken by others or destroyed by pollution and that the fishing waters have been fenced off. We might not notice that the peasant already knows how to farm, but doesn’t have a bit of land to call his own. There is a tendency to assume that individuals and countries everywhere are surrounded by abundant opportunities, and only need to be clever enough to take advantage of them. Sometimes the rich even provide a bit of start-up capital. Even so, most of the poor stay poor, and their ranks are steadily replenished.

In many places, the most serious problem at the local level is the lack of opportunities to do meaningful, productive work. Too many people with far greater potential are spending their days working unproductive farms, pulling carts, fetching water, or doing mind-numbing physical work on assembly lines. At the global level, the steadily widening gap between rich and poor is not likely to be sustainable. Those who are at the top end have not given much thought to the problems the widening gap might produce.

International agencies might recognize that people are embedded in social systems that limit their possibilities, but they tend to emphasize the failures of the individual rather than of the social context. Not only individuals, but countries too, are embedded in social systems that systematically keep the poor and powerless in their sorry condition.

The global marketplace is not an equal-opportunity marketplace. Many countries stay on the bottom no matter how much outsiders try to help them. To some extent that is due to forces within the country such as armed conflicts, rapid population growth, and corrupt leaders. To some extent it is the result of international political and economic forces that keep them down. For example, massive subsidies of agricultural products in richer countries result in their dumping large quantities of these products in poorer countries, undermining those countries’ agricultural sectors. Sometimes poor countries cannot get access to the markets of rich countries to sell their export products, and then they can do that only if they sell at rock-bottom prices. Not only individuals but also entire countries have, in effect, become unemployed, totally marginalized by the global economic system. Many people who are employed work on unfavorable terms, which gives them little prospect of ever catching up. Chronic malnutrition is a concrete manifestation of disparities in power. Hunger results from having too few choices and being subject to choices made by others.

Of course poor countries ought to take responsibility and try to pull themselves up. However, with the playing field tilted sharply against them, it becomes a Sisyphean struggle. They climb a bit and then some natural disaster or, more predictably, inflation, overtakes them and pushes them back. The global economic system favors the powerful.

Seeing hunger as a matter of deficits among its victims means seeing it as mainly a technical problem, not a political problem. It is a blame-the-victim approach that deflects attention away from the role of the larger social system in which the victim is embedded (Kent 2003a). It supports the cold view that the problem belongs to those other people, not to all of us together. It is like saying that a brother’s illness is that brother’s problem, not the family’s problem.

The rhetoric at global summits on food and nutrition suggests that we are all eager to end these problems. If everyone really wanted hunger to end, surely it could be ended. The fact that it has not ended should lead us to suspect that there is a political dimension to the issue, in the sense that there are different people with different interests pulling in different directions. Indeed, when we look at the concrete actions that are taken or not taken in relation to hunger, often we see that the action does not match the talk. As shown in Chapter 11 of this book, the declarations from the global summits on food and nutrition follow that pattern.

Some national governments do very little about food and nutrition problems (Action Aid 2009). Some, such as India and the United States, do offer many large-scale food and nutrition programs for their own people. But still the problems persist. Why?

Part of the explanation is that the programs don’t reach all who...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- 1. Nutrition Problems

- 2. Widening Gaps

- 3. Food Trade

- 4. Rights-Based Social Systems

- 5. The Human Right to Adequate Food

- 6. Global Obligations

- 7. Nutritional Safety Nets

- 8. Household Food Production

- 9. Community-Based Nutrition Security

- 10. Food/Nutrition Policy Councils

- 11. Diagnosing Global Approaches

- 12. Multi-Level Strategic Planning

- Appendix: American Samoa Executive Order

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Ending Hunger Worldwide by George Kent in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.