- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Female Economic Strategies in the Modern World

About this book

This collection of essays looks at the various ways in which women have coped financially in a male-dominated world. Chapters focus on Europe and Latin America, and cover the whole of the modern period.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Female Economic Strategies in the Modern World by Beatrice Moring in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Economic Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 WIDOWS, FAMILY AND POOR RELIEF IN ENGLAND FROM THE SIXTEENTH TO THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

Introduction

In 1789 Mary Chilcott from Aff Piddle in the county of Dorset, a widow with four children, the eldest of whom was nineteen, was spending six shillings and six pence a week on bread and flour.1 This represented 89 per cent of all her expenditure on food and 69 per cent of all her expenditure. Apart from bread and flour the only other food purchases were 4 pence on bacon, 6 pence on tea, sugar, butter and cream and I penny on yeast.

Just over a century later in York, another household consisting of a widow aged sixty-three and a daughter aged twenty spent 22 per cent of their income on meat and 16 per cent on bread. For these two women we also know what they ate at every meal in the first week of March in 1901. For example, on Monday 5 March 1901, their breakfast consisted of bread, butter and coffee, dinner (taken in the middle of the day) of meat, potatoes, bread and tea and a tea (evening meal) of bread, butter and tea. Indeed, breakfast was always limited to bread and butter and either tea or coffee, except on Saturday. Nor did tea vary greatly, involving usually just bread, butter and tea. Dripping was added on Wednesday and Thursday and on Friday the bread was toasted. Supper was only eaten on Saturday and Sunday. Five of the seven dinners included meat as did one of the suppers. However, monotonous this diet (no vegetables other than potatoes and onions) and no fruit were purchased during the week), the variety of food was greater than the widow in Aff Piddle had available at the end of the eighteenth century. Mother and daughter in this York household were also eating meat much more frequently than almost all the widows who headed households in the working-class district of St George in the East in East London in 1845. Only 4 per cent of such households ate meat more than five times a week. Nearly half had meat just once a week.2

Detailed evidence on the diet of a somewhat more prosperous widow can be found in the study by M. F. Davies of households in Corsley, Wiltshire.3 This ‘aged’ widow of a small farmer in Corsley, Wiltshire, was supported by her children and according to Davies she experienced neither primary nor secondary poverty in that her income was not only sufficient for her needs but provided an adequate surplus. Analysis of the budget suggests bread was only 8 per cent of the total (given and bought) while meat was 61 per cent.4 Her meals on Monday 14 January 1906 were for breakfast at 9am, bread, butter and tea, for dinner (taken at 1pm), fried bacon and potatoes, tea at 4pm, buttered toast and tea), and supper at 8:30pm, bread and cheese and a glass of beer. During the fortnight that a record of her meals was kept, bacon featured in half of the breakfasts, bacon, ham and pork in thirteen of the fourteen dinners and cheese or meat and a glass of beer at all fourteen suppers.

Such detailed budgets provide fascinating details on the standard of living of particular widows but with so few budgets available for study the evidence that they provide has to be used cautiously. It would, for example, be unwise to rely on this evidence alone to infer how the standard of living of widows may have varied either from place to place or over time. Davies was certainly of the opinion that the living standards of the poor had improved significantly in the later nineteenth century. Cottagers, she remarked, would around 1880, have bought one ounce of tea or coffee and one pound of sugar to last them the whole week. Fifteen years later the same families would purchase every week a quarter pound of tea and three pounds of sugar.5 From other information provided by Davies, it appears that the diet of the poor in Corsley was more nourishing than the diet of the poor in York in that in Corsley garden produce provided a large proportion of the food with even the poorest households consuming onions, greens and other vegetables in addition to potatoes. Green vegetables featured in the meals of the two widow headed households in Corsley whose purchases of food are recorded but were rarely part of the meals of the two widow headed households in Rowntree s study of York.6

As well as recording the expenditure patterns of widow-headed households, information is required concerning their sources of income. The households of the three widows whose economic circumstances were detailed above were supported in different ways. Only one, the household of the widow in Aff Piddle, received any support from the Poor Law and the majority of the income of even this household (70 per cent) was derived from the earnings of the widows children. The widows household in York was entirely supported by what the widow and her adult, but delicate, daughter were able to earn. In the four-week period covered by the budget, the widow was the principal earner providing 60 per cent of the income.7 The third widow, from Corsley, lived alone but was entirely supported by relatives. A daughter paid her rent and sent bacon, butter, potatoes and wood if her own supply did not last out. Other children assisted occasionally. A niece, living near, provided care.

To help determine the extent of the poverty experienced by these and other widows, comparisons can be made with the income and expenditure patterns of other households that social investigators such as Rowntree and M. F. Davies classed as poor such as the households of labourers. It is more difficult given the scarcity of detailed budgets for female headed households to discover whether the expenditure patterns of these widows are representative of those of other widows at that time although some comparisons are possible with the budgets of a few other female headed households at the end of the eighteenth century and for Corsley in the early twentieth century8 Information about the sources of income of widow headed households in different periods can also be obtained by analysing the various surveys of the poor that detail both their earnings and the payments of out relief authorized by the Overseers of the Poor.9 Even in the absence of information on the earnings of specific individuals, some inferences are possible about the relative contribution of earnings and poor relief to the household budgets of both widows and male headed households by comparing average wage levels of men and women in a given area with the amounts paid out by the Overseers in the form of out relief.10

Widows Receiving Out Relief

There are many gradations of poverty. Steven King when examining the incidence of poverty in four English parishes in the later eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, listed in addition to persons receiving out relief from the Overseers of the Poor, persons in receipt of charity, paying a low rent, those whose goods had been sequestered, were late in paying poor and other rates, or excused payment of taxes.11 In both periods, persons receiving out relief constituted less than a fifth of all those identified as poor and just over 10 per cent of the total population.12

Calculations on similar lines can be made for widows. For example, analysis of the census of Cardington, Bedfordshire, that was taken in 1782 suggests that 82 per cent of all the widows in the parish could be classed as poor as their late husbands had been either labourers or craftsmen. However, only 55 per cent of these widows were receiving poor relief when the census was taken. In the Dorset parish of Corfe Castle which comprised both a small market town and rural districts, a higher proportion of poor widows in Corfe Castle than in Cardington were receiving out relief (71 per cent).13 However, fewer widows were identified as poor in Corfe Castle than Cardington in that only 55 per cent were recorded in that they were either wage earners or in receipt of poor relief. Two conclusions are clear: first not all widows were poor, and secondly, of those widows who were considered poor by their contemporaries, a considerable minority did not receive out relief.14

As King has noted,15 there are a number of reasons why it is often difficult to calculate precisely both the number of persons who were poor and those dependent on out relief. Major problems are that dependants of persons receiving poor relief might not be included in the lists of recipients and that, given the rarity of local censuses, it is often necessary to estimate the total population of a parish.16 Counts of the number of widows in poverty in Cardington and Corfe Castle avoid these particular problems as the total population is known, as is the number of widows in or out of poverty, as indeed is the number of their dependants. The problems that remain are that the population of poor widows is not defined in exactly the same way (although it appears to be broadly compatible) and the Overseers of the Poor may have differed in their assessment of the degree of poverty that merited the granting of out relief. Nevertheless it is clear by referring back to Kings estimates of the proportion of the total population in poverty or receiving out relief, that higher proportions of widows than of the overall population were poor and that higher proportions of those who were poor were awarded out relief.

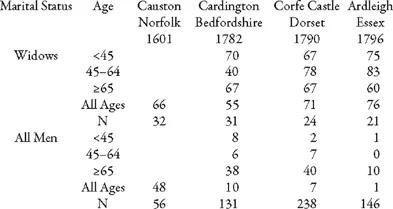

Further details on the proportions of poor widows who received assistance from the poor Law in the form of out relief are set out in Table 1.1. The populations included in addition to Cardington and Corfe Castle are Causton in Norfolk and Ardleigh in Essex for which information is available on the numbers of poor and those receiving out relief in 1601 and 1796 respectively.17

Two particular issues are considered: first, a comparison of the proportions of poor widows and poor men awarded out relief, and, secondly, examination of the variation by age in the proportions receiving relief. In all four communities, out relief was granted to more than half of the widows deemed to be poor but awarded to 10 per cent or less of poor men in Cardington, Corfe Castle and Ardleigh. Only in Causton in 1601 were appreciable numbers of poor men assisted by the Poor Law through out relief.

Table 1.1: Widows and men in receipt of outdoor poor relief as a percentage of the population at risk of poverty in four English parishes.1

1 Population at risk of poverty has been defined as follows:

Causton:...

Causton:...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Contributors

- List of Tables

- Introduction

- 1 Widows, Family and Poor Relief in England from the Sixteenth to the Twentieth Century

- 2 Survival Strategies of Poor Women in Two Localities in Guipuzcoa (Northern Spain) in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries

- 3 Women, Work and Survival Strategies in Urban Northern Europe before the First World War

- 4 Women, Households and Independence under the Old English Poor Laws

- 5 The Economic Strategies of Widows in Switzerland from the mid-Nineteenth to the mid-Twentieth Century

- 6 Mexico: Women and Poverty (1994–2004): Progresa-Oportunidades Conditional Cash Transfer Programme

- 7 Gender and Migration in the Pyrenees in the Nineteenth Century: Gender-Differentiated Patterns and Destinies

- 8 Women and Property in Eighteenth-Century Austria: Separate Property, Usufruct and Ownership in Different Family Configurations

- Notes

- Index