![]() PART I.

PART I.

Towards a Common Language: Critically Exploring Key Concepts![]()

Chapter 1

Globalisation: Trends, Limits, and Controversies

MIN-HYUNG KIM and JAMES CAPORASO

CONTENTS

1. Introduction

2. Conceptualisation of Globalisation

3. Degrees and Patterns of Globalisation

3.1 Trade Flows

3.2 Capital Flows

3.3 MNC Activities

4. Critical Issues

4.1 Global and Regional (European) Imbalances

4.2 Openness vs Protectionism

4.3 Regional and Country-Based Financial Crises

4.4 Global Governance

5. Globalisation and Europe

5.1 Globalisation and European Integration

5.2 Globalisation and the Eurozone Crisis

6. Conclusion

Test Questions

Further Reading

Web Links

SUMMARY

This chapter briefly addresses the ongoing debate of globalisation and provides its conceptualisation in three major dimensions (economic, political, and cultural). Then, it explores the driving forces of globalisation and assesses the degrees and patterns of globalisation on the basis of some key indicators (that is, trade flows, capital flows, and MNCs activities). Finally, after examining the critical issues of globalisation (that is, global and regional imbalances, openness vs protectionism, country-based and regional financial crises, and global governance), the chapter concludes with some comments on the implications of globalisation for multilateralism.

1. INTRODUCTION

Over the last two decades, the term ‘globalisation’ has become a buzzword among social scientists, regardless of their specific positions. Numerous books and articles have been published with different interpretations of its causes, consequences, and implications. While the debate is intensifying and will not be concluded in the foreseeable future, most agree that the globalisation of trade and finance is transforming the global economic landscape, global welfare, inter-firm and interstate relations, and ultimately world politics. Indeed, there is strong evidence for a globalised marketplace, such as ever-expanding international trade and investment and the contagion effects of financial crises in the world economy.

Nonetheless, it is worth noting that no single account of globalisation has obtained the status of orthodoxy. Competing perspectives are hardening their positions as the globalisation process deepens, but neither the globalist nor the sceptical thesis exhausts its complexity. In fact, even within each position there are considerable differences of emphasis regarding the interpretation of its historical development and normative stance (Held and McGrew 2000: 2).

To begin with, globalists point to the ‘historically unprecedented scale and magnitude of contemporary global economic interaction’ and ‘the ways in which national governments are having to adjust constantly to the push and pull of global market conditions and forces’ (Held and McGrew 2000: 23). They argue that the deepening process of globalisation is transforming State power and authority, because social and economic processes operate predominantly at the global level, making the nation-state as the primary unit obsolete (Ohmae 1995; Dicken 1998; Friedman 2007). Generally accepting the thesis of ‘triumphs of the market over the state’, globalists stress ‘a conception of global change involving a significant reordering of the organizing principles of social life and world order’ (Held and McGrew 2000: 7) and downplay the costs associated with global integration.

Sceptics of globalisation (Hirst 1997; Samuelson 2004; Drezner 2007), on the other hand, view it as a primarily ideological construction or a necessary myth, through which States discipline their citizens to meet the requirements of a global free market. They argue that the discourse of globalisation legitimises the consolidation of Anglo-American capitalism represented by the so-called Washington Consensus (Held and McGrew 2000: 5). Contrary to globalists, sceptics contend that States are as powerful as before and national governments remain central to the governance of the global economy (Drezner 2007). Even in the case of the European Union (EU) where national sovereignty has most significantly been compromised, globalists maintain that States ‘effectively pool sovereignty in order to enhance, through collective action, their control over external forces’ (Held and McGrew 2000: 22). In general, anti-globalists assert that the costs of globalisation far exceed its benefits.

BOX 1.1 THE WASHINGTON CONSENSUS

The Washington Consensus refers to a set of neoliberal policies that emphasises free trade and capital mobility, such as trade liberalisation, privatisation, deregulation, fiscal discipline, banking reform, flexibilisation of labour markets, and cutting back of trade union rights, etc.

2. CONCEPTUALISATION OF GLOBALISATION

Although the precise meaning of globalisation remains contested, its core concept denotes the entrenched and enduring patterns of worldwide interconnectedness, rather than mere random encounters (Held and McGrew 2000: 3). Beyond simple interdependence of States and societies, globalisation refers to interactions among various actors (for example individuals, firms, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), international organisation, States) in different regions of the world. While it certainly involves the intensification of interstate and interregional interconnectedness, globalisation implies neither homogenisation/universality nor equity (Keohane and Nye 2000: 106). Given its multi-layered and complex processes, it is useful to untangle globalisation in terms of three major dimensions: economic, political, and cultural.

Economic globalisation refers to growing interdependence and increasing integration of trade, finance, and investment among States and firms on a global scale. It points to the increasing openness of markets for goods, services, capital, and, to a lesser extent, labour. Among others, it pays close attention to the activities of MNCs, the reduction of protectionist trade barriers (for example tariffs, non-tariff barriers (NTBs)) among developed and developing countries, and a rapidly growing level of capital flows and financial market integration.

Political globalisation primarily concerns the impact of globalisation on the nature, role, and function of the State (Hebron and Stack 2009: 21), which regulates myriad activities of our contemporary social life, including issuing birth and death certificates, collecting taxes, providing security, education, and healthcare, and so on (Held and McGrew 2000: 8). Its main discourse revolves around the link between territory and State capacity/control in an increasingly interdependent world. It also pays attention to the rise of NGOs (for example Amnesty International, Green Peace, Doctors without Borders) as well as international organisations (for example the World Trade Organization [WTO], the EU, the ASEAN Regional Forum [ARF], the Arab League) and their impact on national policymaking authority.

Cultural globalisation refers to a rapidly increasing flow of cultural goods. It denotes the transfer of ideas, values, local cultures, religious beliefs, communication patterns, business and social practices, and so on. The deepening process of cultural globalisation may create a new sense of global belonging – that is, ‘a supposed universal homogeneous culture in which all ethnic, linguistic, racial, and religious distinctions and discords are washed away’ – and provide a modernised and rationalised global culture that promotes greater understanding (Hebron and Stack 2009: 23), but it can also threaten basic group (for example national) identities as well as loyalties to local communities. For example, in The Clash of Civilizations, Samuel Huntington argues that the modernising influences of Western civilisation produce a severe cultural backlash among peoples in different parts of the world, especially in the Middle East: ‘What is universalism to the West is imperialism to the rest’ (1996: 184).

As for the driving forces of globalisation, the technological revolution has been the primary engine of contemporary globalisation. It has been responsible for lowering transportation costs and facilitating higher levels of global production and commerce. In particular, the information revolution such as the creation of the Internet, Facebook, Twitter, international broadcasting networks, and so on has reduced communication costs and made possible the emergence of a global village by accelerating economic, social, and political interactions among people, firms, international institutions, and States across the world’s major regions.

3. DEGREES AND PATTERNS OF GLOBALISATION

3.1 Trade Flows

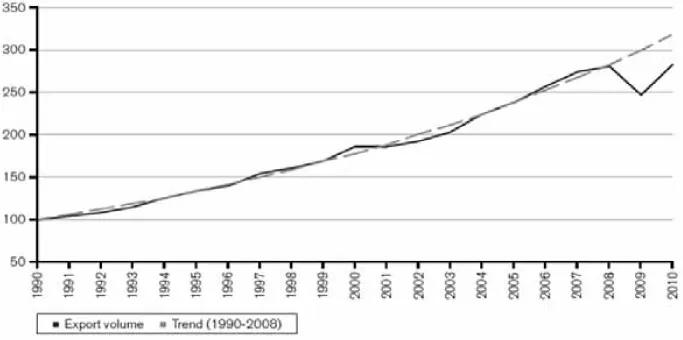

International trade is a crucial, but most heatedly debated, dimension of globalisation. Due to trade liberalisation, which was encouraged by the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and its successor the WTO, international trade since The Second World War has dramatically increased. Indeed, the index of trade integration (that is the difference between the growth rate in world trade and the growth rate in world gross domestic product) shows that international trade has become increasingly global over the last several decades. As Kegley and Blanton (2012–13: 357) notes, ‘since The Second World War, the world economy (as measured by gross domestic product, GDP) has expanded by a factor of six while global trade has increased twenty times’. And according to the WTO, world merchandise exports grew four times faster than world GDP in 2010 (WTO 2011b: 14). To be sure, international trade experienced a substantial decline in times of economic crises, but the general trend undoubtedly shows a consistent growth. This is demonstrated by the recent data on the world merchandise trade in Figure 1.1. It reveals that world merchandise trade has consistently grown since 1990, except for the periods of the Asian financial crisis of 1997–98 and the global financial crisis of 2007–08.

There are some important developments in international trade that are worth mentioning. First, the rapid increase and spread of preferential trading agreements (PTAs) since the 1990s is noteworthy. For instance, the number of PTAs was about 70 in 1990. In 2010, however, the number in force reached about 300. In fact, except Mongolia, all WTO members currently belong to at least one PTA. Also important to note is that about 50 per cent of the PTAs currently in force are not strictly ‘regional’ and the proliferation of cross-regional PTAs has been a major trend of the last decade. At the same time, bilateral trade arrangements across regions (not just bilateral free trade agreements but also plurilateral agreements such as a PTA between MERCOSUR and the Andean Community) have increased substantially, resulting in a further fragmentation of trade relations, with countries belonging to multiple and sometimes overlapping PTAs1 (WTO a 2011: 6). While PTAs generate significant benefits such as the promotion of technology, knowledge transfers, and domestic reforms, they also cause some negative effects due to their nature of trade liberalisation outside the multilateral (that is the WTO) arena: ‘the distortion in trade patterns between “insiders” and “outsiders” which undermine the welfare gains arising from expanded trade’, ‘incentives for inefficient resource allocation’, and ‘the “spaghetti bowl” effect of multiple agreements with separate rules of origin’ (Higgott 2009: 22).

Figure 1.1 Volume of world merchandise trade, 1990–2010 (Indices, 1990=100)

Source: WTO’s World Trade Report 2011

Another important development is the deepening of regional ties in trade in the past two decades. In particular, intraregional trade in Europe, Asia, and North America has significantly increased since the 1990s. In the case of Europe, the share of intraregional trade in Europe’s total exports remained roughly at about 73 per cent between 1990 and 2009. During the same period, Asia’s intraregional trade share in total exports increased from 42 per cent to 52 per cent. North America’s intraregional trade share also increased from 41 per cent to 56 per cent between 1990 and 2000, although it decreased to 48 per cent in 2009 (WTO a 2011: 7) due to the global financial crisis of 2007–08 which originated in the US. Indeed, the recent WTO’s World Trade Developments report reveals that more trade flows are taking place within regions than between regions. For instance, in 2010, 71 per cent of Europe’s exports went to the European region, whereas 53 per cent of Asian trade was directed to Asian countries and about 50 per cent of North America’s exports were headed to the members of the North American Free Treaty Agreement (NAFTA) (WTO b: 12–13).

3.2 Capital Flows

The integration of international financial markets, especially since the early 1990s, has generated a massive increase of global capital flows. Between 1971 and 2006, for example, total annual outflows of FDI rose from about $12 billion to $1.2 trillion (Spero and Hart 2010: 135). Although the amount of global FDI flows substantially decreased in 2008–09 (after its peak in 2007) due to the global financial crisis, the general trend indicates that it is recovering, albeit slowly (UNCTAD 2011).

What is important to note here is that while global capital flows were traditionally North-North rather than North-South, an emerging pattern is that the developing countries in the Global South steadily increased their share of both inflows and outflows. In fact, many LDCs have recently adopted the neoliberal policies of Washington Consensus to facilitate FDI inflows, because they are critical for their job creation and economic development. Thus, challenging the dominance of Western MNCs, many LDCs like BRICs (that is Brazil, Russia, India, and China) have become significant hosts and homes of global FDI (Balaam and Dillman 2011: 441–2). This changing pattern of global FDI inflows is illustrated by following figures. Figure 1.2 reveals the trend of global FDI inflows from 1980 to 2010. While FDI inflows to developed and transition economies reduced in 2010, those to developing economies increased and together with transition economies exceeded 50 per cent of global FDI flows for the first time.

Figure 1.3 shows that in 2010 BRICs were among the top 14 economies of global FDI inflows (that is the rankings of China, Brazil, Russia, and India were...