- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

International Operations Management: Lessons in Global Business uses a fascinating selection of case studies researched during the 'International Operations Management Project', sponsored by the European Commission, to produce a valuable view of businesses in Western and Eastern traditions. Ranging from China Post and Flextronics International (Singapore) to Electrolux, Ford, and GlaxoSmithKline, the studies link conceptual and practical approaches in five areas: international operations management strategy, sourcing and manufacturing, new product development, logistics, and networked organisations. Throughout, the authors compare the Western and Eastern approaches to business, and introduce theory to clarify the comparison and the real consequences of internationalisation. With its balance of theoretical and applied content, this volume, created from an exciting collaboration between universities and schools of management in Europe and China, serves as both a primary and supplementary source for higher level students and educators, and as a worthwhile read for interested practitioners.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access International Operations Management by Alberto F. De Toni in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

International Operations Strategy

CHAPTER 1

The Pacorini Case Study: Deliberate and Emergent Strategy

The business model as an interpretative tool for strategic evolution

1.1 Theory

1.1.1 APPROACHES FOR STUDYING COMPANIES’ STRATEGIES

The field of strategic management is rich with theoretical contributions which, unfortunately, are often difficult to categorise. One reason for this difficulty is the duality between theory and practice and the need to meet the often conflicting expectations of stakeholders who are interested in these subjects (Pettigrew et al., 2002). Second, the field’s current stage of development exists in a constantly changing context; contemporary strategic management is only 40 years old, during which time its practitioners have focused on laying down disciplinary foundations and building a reasonably consistent intellectual language in an attempt to establish some basic patterns in what is and is not known about strategic issues (Pettigrew et al., 2002). We can count several models and tools developed by business schools, universities and consulting companies, each of which captures only few strategic issues at a time because competition in business environments has multiple, interrelated facets (Mintzberg et al., 1998). Thus we believe it is only possible to talk about different approaches when interpreting the strategic choices of a company in terms of its own history.

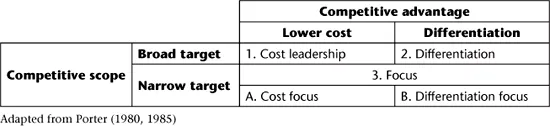

The first aim of this case study is to underline the point that different approaches can be adopted simultaneously when analysing certain firms’ strategic moves in a given industry. For example, Porter’s (1980, 1985) three generic competitive strategies and Miles and Snow’s (1978) four strategic typologies are well-recognised ways of interpreting and classifying companies’ strategies. The second purpose of this case study is to propose a new way of interpreting those strategic moves. We call this the business model approach, and we believe it is effective in catching the real drivers of strategic actions when studying companies’ evolution over time. We will dedicate the following paragraphs to describing and explaining these approaches. The Pacorini Group’s case study will be analysed subsequently.

1.1.2 THREE GENERIC COMPETITIVE STRATEGIES

Generally speaking, we can say that competitive strategies represent a set of guidelines aimed at creating a sustainable competitive position within a certain industry and thus realising a economic superior result, on average, to that of competitors. The fundamental basis of such above-average performance in the long term lies in a company’s sustainable competitive advantage. Though a firm can have lots of strengths and weaknesses with respect to its competitors, Porter (1980, 1985) recognises two fundamental types of competitive advantages: low cost and differentiation. These two basic competitive advantages, combined with the variety of activities through which a company seeks to achieve them, lead to three generic competitive strategies that companies may pursue (Porter, 1980, 1985):

1. global cost leadership,

2. product differentiation,

3. focus.

In theory, a company could follow more than one strategy successfully at a time, but this is uncommon because each of these strategies requires a certain level of commitment and organisational effort, without which the chosen strategy would be weakened. Thus, the notion underlying the concept of generic strategies is that competitive advantage is at the heart of every strategy and achieving competitive advantage requires a company to make a set of choices.

Cost leadership is perhaps the clearest of the three generic strategies. When a firm designs, produces and markets a product more efficiently than competitors, it has implemented a cost-leadership strategy (Allen et al., 2006). The cost reduction strategies, mass production and distribution for gaining economies of scale, design for operations, learning curve benefits, and the like (Beheshti, 2004; Freeman, 2003; Mintzberg et al., 1998), along with other factors such as possession of exclusive technologies, preferential access to supply and distribution channels, favourable plant locations and so on, will further help a firm to maintain a low cost base. Generally speaking, there are several sources of cost advantages and they usually depend on an industry’s structure (Porter, 1980, 1985). A low-cost producer will typically find and exploit all sources of cost advantage and sell a standard, no-frills product or service. A process that goes against cost minimisation should be outsourced to other organisations to maintain a low cost base (Akan et al. 2006). If a firm can achieve and sustain overall cost leadership, it will be an above-average performer in its industry, meaning that the company earns higher returns at equivalent or lower prices than its competitors (Porter, 1980, 1985). We want to remark here that the cost leader’s objective is not necessarily to sell products at lower prices than its rivals but to obtain a favourable cost structure. Lowering prices could be a necessary move to increase sales if clients do not perceive the company’s product positively relative to competitors. For relatively standardised products, which offer features acceptable to many customers, the lowest competitive price could be a competitive advantage, helping the company increase its market share (Porter 1979, 1986, 1987; Murray, 1988; Bauer and Colgan, 2001). However, low cost leadership often brings less customer loyalty (Vokurka and Davis, 2004) and relatively low prices may also result in customers’ undervaluation of the product’s quality (Priem, 2007). Such impressions may enhance a customer’s tendency to choose a higher-price product that projects an image of quality. This phenomenon means that a cost leader must not ignore the basis of differentiation, or it risks nullifying the benefits of its favourable cost position (Porter, 1980, 1985). Therefore, a cost leader must achieve proximity in terms of product differentiation relative to its rivals. Parity on the basis of differentiation allows a cost leader to translate its cost advantage directly into higher profits than its competitors (Porter, 1980, 1985).

In a differentiation strategy, a firm seeks to be unique in its industry along some dimensions that are of great importance to buyers. The company selects one or more attributes of this kind and uniquely positions itself in the industry to better meet buyers’ needs. The firm is then rewarded for its uniqueness with a premium price (Porter, 1980, 1985). The means for differentiation are peculiar to each industry. We can count among them product design, brand and image, technology, functional features, after-sales services, delivery systems, marketing and promotion and a wide range of other factors (Porter, 1980, 1985). A firm that can achieve and sustain differentiation will be an above-average performer in its industry if its premium price exceeds the extra costs incurred by being unique. Thus a differentiator must always seek ways of differentiating that lead to a premium price greater than the cost of differentiating. Nonetheless, such a firm cannot ignore its cost position because its premium prices can be nullified by a markedly inferior cost position. A firm must truly be unique in some regard, or be perceived as unique, if it expects to receive a premium price (Porter, 1980, 1985). At the same time, the company has to reach cost proximity relative to its competitors by reducing costs in all areas that do not affect differentiation.

The third generic strategy is focus. This strategy is quite different from the prior two because it entails the choice of a narrow competitive scope within an industry. The focuser selects a segment or group of segments within the industry and tailors its strategy towards serving them, to the exclusion of others. By optimising its strategy for the target segments, the focuser seeks to achieve a competitive advantage in its target segments even though it does not possess a competitive advantage overall. The focus strategy has two variants. In cost focus, a firm seeks a cost advantage in its target segment, whereas in differentiation focus, a firm searches for differentiation in its target segment. Both variants of the focus strategy rely on differences between a focuser’s target segments and other segments in the industry (Porter, 1980, 1985). Segmentation can be conducted according to client behaviours, product or geographical area. Cost focus exploits differences in cost behaviour in some segments, whereas differentiation focus exploits the special needs of buyers in certain niches. Such differences imply that these segments are poorly served by broadly targeted competitors who serve them at the same time that they serve others. Table 1.1 summarises these three generic competitive strategies.

Table 1.1 Three generic strategies

The three generic strategies are alternative approaches to dealing with competitive forces. If a firm attempts to achieve advantages on all fronts, it may achieve no advantage at all. For this reason, Porter (1980) argued that to be successful over the long term, a firm must select only one of these three generic strategies. Otherwise, firms that adopt more than one generic strategy will be ‘stuck in the middle’ and will not achieve a competitive advantage. A firm that is stuck in the middle will compete at a disadvantage because the cost leader, differentiators, or focusers will be better positioned to compete in any segment. Nevertheless, a stuck-in-the-middle company may earn attractive profits if the structure of its industry is highly favourable, or if it is lucky enough to compete with other stuck-in-the-middle companies. Nevertheless, Porter argued that firms able to succeed at multiple strategies often do so by creating separate business units for each strategy.

However, several commentators (Miller, 1992; Baden-Fuller and Stopford, 1992) have questioned the use of generic strategies, claiming they lack specificity and flexibility: a single generic strategy is not always the best one because customers often seek multiple dimensions of satisfaction within the same product, such as a combination of quality, style, convenience and price. Strategic specialisation may leave serious gaps or weaknesses in product offerings, ignore important customer needs or be easy for competitors to counter or imitate; in the end, this strategy can cause inflexibility and narrow an organisation’s vision. In other words, pursuing a unique generic competitive strategy could mean ignoring new opportunities. Therefore, other authors’ attention is given to the fact that successful strategies do not always need to follow strictly the three directions indicated by Porter. Instead, strategies may also be a mixture of choices that do not necessarily focus on a single competitive advantage but, on the contrary, enhance a set of unique skills and capabilities, avoiding the risk of losing resiliency and adaptability that goes along with concentrating on a single strength.

1.1.3 FOUR STRATEGIC TYPOLOGIES

Miles and Snow (1978) adopt a different perspective: instead of concentrating on the choice of competitive advantage and the right strategy to achieve it, they noticed that, within a single industry, patterns of behaviours are recurrent. In particular, four main archetypes of organisations are identifiable:

1. defenders

2. prospectors

3. analysers, and

4. reactors.

Defenders are organisations that have narrow product-market domains and usually do not tend to search outside of those domains for new opportunities. Because of this narrow focus, these organisations seldom need to make major adjustments in their technology, structure or methods of operation. In contrast, they primarily devote their attention to improving the efficiency of their existing operations (Miles and Snow, 1978). Thus defenders typically direct their products or services to a limited segment of the total potential market, and the segment chosen is frequently one of the healthiest of the entire market. By building strong and stable relationships with their clients, these companies are able to stabilise their operations with increasing efficiency. Consequently, defenders do well in competing based on either price or quality.

Prospectors are organisations that almost continually search for market opportunities, and they constantly experiment with potential responses to emerging environmental trends. Thus these companies are often the creators of change and uncertainty to which their competitors must respond. For these types of organisations, maintaining a reputation as an innovator in product and market development may be as important as, and perhaps even more important than, high profitability. In contrast, due to their strong concern for product and market innovation, these firms usually do not show high levels of efficiency (Miles and Snow, 1978). The prospectors’ domain is generally broad and in a constant state of development: the systematic addition of new products or markets, frequently combined with retrenchment in other parts of the domain, requires that these companies be flexible and adaptive.

Analysers are organisations that operate in two types of product-market domains, one that is relatively stable and the other one changing. In their stable areas, these companies operate routinely and efficiently using formalised structures and processes. In their more turbulent areas, top managers closely observe their competitors to come up with new ideas and then rapidly adopt those that appear to be the most profitable (Miles and Snow, 1978). Thus, the analyser is a unique combination of the prospector and defender types. A true analyser is an organisation that minimises risk while maximising opportunities for profit through an adaptive approach where the key word is balance. The analyser’s domain is therefore a mixture of products and markets, some of which are stable and established while others are changing and evolving. With the stable portion of its domain reasonably well protected, the analyser is free to imitate the best of the products and markets developed by prospectors. This practice is successfully achieved through extensive marketing surveillance mechanisms. Whereas the prospector is a creator of change in the industry, the analyser is an avid follower, aiming to exploit the most promising innovations without carrying the costs of extensive research and development (Miles and Snow, 1978).

Reactors are organisations in which top managers frequently perceive change and uncertainty occurring in their organisational environments but are unable to respond effectively. Because this type of organisation lacks a consistent strategy–structure relationship, it seldom makes adjustments of any sort until forced to do so by environmental pressures. A reactor exhibits a pattern of adjustment to its environment that is both inconsistent and unstable; this type of organisation lacks a set of response mechanisms that can be put into effect con...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- About the Editor

- About the Co-editors

- Introduction

- PART 1 INTERNATIONAL OPERATIONS STRATEGY

- PART 2 INTERNATIONAL NETWORKED ORGANIZATION STRATEGY

- PART 3 INTERNATIONAL NEW PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT

- PART 4 INTERNATIONAL SOURCING AND MANUFACTURING

- PART 5 INTERNATIONAL LOGISTICS

- Index