Matters of Race, Culture, and Respect: An Introduction

Royalty routinely visit the White House in America, but how often do kings bring a guitar named Lucille to the president’s home? The King of the Blues, Riley “B. B.” King, performed for President Bill Clinton and First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton on July 28, 1999, as part of a millennial celebration of American culture. King reigned as the featured performer among four other internationally recognized American artists: John Cephas and Phil Wiggins, Marcia Ball, and Johnny Lang. Later that year, the show was broadcast nationally on public television as “The Blues: In Performance at the White House.” According to PBS, the series was designed “to showcase the rich fabric of American culture in the setting of the nation’s most famous home.”1

For African American performers like King and Cephas, the significance of the White House performance cannot be minimized. B. B. King and John Cephas began performing blues for Black audiences in the era of legalized racial segregation, which limited access to audiences in White social arenas. Webs of inequitable laws and unjust customs enforced racial division in the United States constructed around a binary: Whiteness in opposition to Blackness.2 The blues grew from longstanding African American oral traditions shaped since the 1870s by working people, itinerant musicians, and urban migrants in Black social settings. The influential music has informed the sounds and lyrics of jazz, vaudeville, Tin Pan Alley pop, gospel, rhythm and blues, rock and roll, country, musicals, art music, and hip hop within and without the United States—not to mention poetry, literature, and the visual arts. Throughout the music’s history, acknowledgment of the cultural value of Black vernacular music has been relatively rare in White social arenas, which routinely have diminished Black cultural contributions to “American” arts.

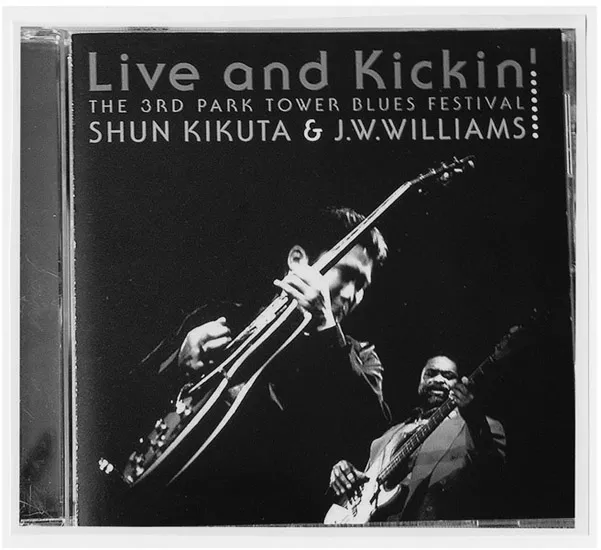

The broadcast of “The Blues: In Performance at the White House” acclaims the cultural value of this African American music in the United States. It pays respect to the fact that Black artists have spread appreciation for African American traditions to audiences of varied cultural backgrounds within and without the United States (Figure 1.1). Although racial barriers restricted the music’s flow beyond Black American community settings through the 1950s,3 the participation of White American performers Marcia Ball and Johnny Lang illustrates the interracial appeal of blues that has grown in the United States. At the time of the White House performance, White fans dominated the national blues audience, while African American performers remained prominent among those widely recognized as creative leaders of the blues.

Figure 1.1 The recording project Live and Kickin’ (BS-002) by Shunsuke “Shun” Kikuta and J. W. Williams evokes the international and transcultural dynamics of contemporary blues scenes. The 1999 release documents the collaboration of Kikuta, who hails from Japan, and Williams, a Chicagoan, with other American and Japanese artists at Tokyo’s third annual Park Tower Blues Festival. Kikuta and Williams played regularly in Chicago’s internationally recognized, top-level blues scene.

The broadcast provides a glimpse of the blues in America in the late 1990s. B. B. King delivered three songs in his characteristic style flavored by Memphis rhythm-and-blues bands, including his signature tune “The Thrill Is Gone” (1969) and his “Paying the Cost to Be the Boss” (1968). The acoustic guitar/harmonica duo of John Cephas and Phil Wiggins showcased the eastern Piedmont regional style of the early twentieth century by performing two songs popularized after World War II. Pianist Marcia Ball, who honed her blend of early New Orleans rhythm and blues in the musical confluence of Austin, Texas, in the 1970s, presented her “St. Gabriel.” The young crossover guitarist Johnny Lang began with a song by blues-rocker Tinsley Ellis, showing the close relationship of blues and rock, a link which continues to appeal strongly to a predominantly White blues audience. Sharing the small, well-lit stage in a closing finale, the artists collectively demonstrated the centrality of Black cultural approaches to performance.4

In many ways the broadcast projected an intergenerational, interracial moment of partially shared culture in a symbolic, national institution. In the political contexts of the twilight of the Clinton administration, we also could read the performance as an immediate comment on the scandals and impeachment hearings of the late 1990s. (Perhaps the lyrics of King’s “Paying the Cost to Be the Boss” and “The Thrill Is Gone” spoke to Bill and Hillary Clinton.)5

But the varied musical repertoire and styles of the performance, as well as the long history of the blues in Black American communities, encourage a more multilayered and polyvocal interpretation. We can more fully understand blues in its contemporary inter-racial and transcultural settings when we analyze it in light of the music’s larger cultural context. From this perspective, analysis considers the values that people have used over time to perform and interpret blues music. Experiences of performers and audiences reflect some of these legacies.

A historical perspective on blues reminds us that people have embraced, but also reinterpreted, Black traditions of blues according to values for music performed in varied cultural contexts inside and outside African American communities. From the inception of the blues in the late 1800s through the 1940s, the mass of Black America used blues music to voice, contemplate, and musically embody Black alternatives to White supremacy. Vaudevillian Maggie Jones sang, for example:

Goin’ where they don’t have no Jim Crow laws,

Goin’ where they don’t have no Jim Crow laws,

Don’t have to work here like in Arkansas.6

At this time and throughout much of the twentieth century, Jim Crow laws sanctioned the violently enforced denial of equitable work contracts, education, legal justice, and voting rights. Particularly in Black communities of agricultural and working-class laborers, blues performances commented on “the facts of life” outside the immediate domain of White social order. Even as the popularity of blues music has varied in Black communities, many African Americans have embraced blues as a metaphor for common political and cultural experiences of Blacks in the United States.

Race remains a structure of social stratification despite the dismantling of Jim Crow segregation. The development of scenes for blues performance outside Black community settings has required negotiations of values that navigate the tensions of racial dynamics in the United States. Black blues masters, like B. B. King and John Cephas, have used the entertainment industry to cross a historical Black–White social divide in America. Although this journey has created a route through which people of varied cultural identities have enjoyed, studied, performed, and produced blues music (Figure 1.1), the odyssey holds acute significance for African Americans who have experienced Eurocentric privilege as a disadvantage.

The subject of social race7 has continued to ignite debates over the significance of relationships between Blacks and Whites in the blues, which is both art and business. In this respect, the blues has remained close to views of “real life” in America. At the time of the White House performance in 1999, “people of color” disproportionately faced socioeconomic struggles of poverty, discrimination, and more limited access to social services. “Colorblind” perspectives, although often issued in opposition to racism, have failed to illuminate the continued significance of racial identity as a “fundamental axis of social organization” in the United States, even as individuals continue to challenge racial barriers.8

From a vantage point that recognizes cultural differences, as well as their harmonies, the White House performance holds multiple meanings that bear stern insights. Like the most incisive and ironic blues lyrics that call us, in the words of Ralph Ellison, to “finger [the] jagged grain”9 of the raw truth, this search for fuller understandings affords empowering outcomes. This essay traces the jagged grain of changes in American social conventions, cultural values, and economic practices that facilitated substantial transcultural participation in blues performances in the 1950s and 1960s. The system of segregation and its changing manifestations in law and custom pivotally shaped the routes through which this newer, largely White American audience base experienced African American blues music.

Monitoring Musical Commodities and Values

White supremacist segregation channeled American experiences into separate and unequal social and economic spheres, although Blacks and Whites clearly influenced one another. Conventional views of relationships between society and the individual expected that ethnic and racial heritage would determine many social behaviors. White America existed in social terms as a legally defined and customarily distinguished sector of people, who often claimed a “pure” European heritage and frequently distanced themselves from the reality of African cultural influences in American life. John Edward Philips argues that “our understanding of White American society is incomplete without an understanding of the Black, and African, impact on White America.”11 The racial codification of American society into Black and White arenas obscured the reality of a culturally pluralistic America, particularly for those Americans whose experiences failed to lead them to question Eurocentric social orders. Life under segregation, however, supported worldviews that placed Black and White societies in opposition.

Racial gatekeeping reflected both aesthetic and economic aims of segregation. Although African American bandleader W. C. Handy had proved the marketability of blues commodities with the success of notated arrangements of the blues songs he first composed in 1912, the music industry discouraged recordings of blues that featured Black vocalists and Black instrumentalists until 1920. Following the vein of minstrelsy, some White popular musicians adopted formal components of blues repertoire and singing style, as in the recordings of Sophie Tucker and the compositions of popular jazzman Hoagy Carmichael, for example.12 Actions of White managers, musicians, advertisers, and consumers converged to restrict Black musicians’ access to work and compensation. From the 1920s to the 1940s blues was at the height of its popularity in Black communities, and segregation restricted Black–White social interaction in theaters, dance halls, radio stations, and record stores, as well as in professions, neighborhoods, and schools. These restrictions were most codified in the southern region of the United States, where African Americans lived in the greatest concentration of population.

The expansion of White audiences for blues recorded by Black performers occurred gradually with regard to conventions of segregation that varied according to region and dynamics of urban–rural interchange. In the northern urban centers with l...