![]()

1

Introduction to Formative Assessment

Overview

In Chapter 1, we present the case that carefully applied formative assessment can promote student learning, achievement, and academic self-regulation. We introduce the three guiding questions related to formative assessment—Where are we going? Where are we now? Where to next?—and illustrate them with an example from a middle school classroom. A brief overview of how formative feedback, in particular, influences learning and self-regulation stresses the fact that good assessment is something done by and for students as well as teachers.

This is a concise book, so we will get right to the point: There is convincing evidence that carefully applied classroom assessments can actually promote student learning and academic self-regulation. These assessments include, but are not limited to, everything from conversations with students, to diagnostic test items, to co-creating rubrics with students that they then use to guide feedback for themselves and their peers. Even traditional multiple-choice tests can be used to deepen learning, rather than simply documenting it.

While classroom assessment has always been an important tool for teachers and learners, its significance is increased in the current context of implementing college and career readiness standards (CCRS). Heightened expectations for all students are reflected in the CCRS, which anticipate deeper learning of core disciplinary ideas and practices. Acquiring deep learning is not analogous to a car that moves from 0–60 miles per hour in 3.2 seconds. Deep learning involves students grappling with important ideas, principles, and practices so they can ultimately transfer their learning to novel situations. Teachers need to understand how student learning is developing so that they can respond to their students’ current learning status along the way to deeper learning, ensuring that students remain on track and achieve intended goals. Essentially, teachers need substantive insights about student learning during the course of its development so their pedagogy can be consistently matched to their students’ immediate learning needs.

Readiness for college and careers not only involves developing deep knowledge within and across disciplines, applying that knowledge to novel situations, and engaging in creative and critical approaches to problem solving; it also involves acquiring learning competencies such as the ability to communicate, collaborate, and manage one’s own learning (National Research Council, 2012). Classroom assessment is a key practice for both teachers and students to support deeper learning and the development of learning competencies.

While both major types of assessment—summative and formative—are important for enhancing student learning, research suggests that formative assessment is especially effective. Summative classroom assessment, including grading, is usually done by the teacher for the purposes of certifying and reporting learning. Formative classroom assessment is the practice of using evidence of student learning to make adjustments that advance learning (Wiliam, 2010). Reviews of research suggest that, when implemented well, formative assessment can have powerful, positive effects on learning (Bennett, 2011; Black, Harrison, Lee, Marshall, & Wiliam, 2003; Black & Wiliam, 1998; Kingston & Nash, 2011). When any high-quality classroom assessment is used for formative purposes, it provides feedback to teachers that can inform adjustments to instruction, as well as feedback to students that supports their learning.

As we will demonstrate throughout this book, feedback is the core element of formative assessment (Hattie & Timperley, 2007; Sadler, 1989). Teachers receive feedback about their teaching and their students’ learning from evidence they obtain while learning is taking place, and students receive feedback from their teachers, peers, and their own self-assessment during the course of learning. In formative assessment, the purpose of generating feedback from these different sources is to help students take action to move forward in their learning.

This book is about how to leverage the power of formative assessment in the service of good teaching, deep learning, and self-regulated learning. We will summarize what we know about how formative assessment influences learning and self-regulation. We will then introduce actionable principles, and illustrate how those principles have been successfully implemented in K–12 classrooms.

The purpose of the book is to make it possible for educators in every discipline and grade level to amplify the instructional influence of a ubiquitous but typically under-powered process—formative assessment. Doing so is likely to help students become more willing to critique and revise their thought processes and their work. As a result, they will learn more and obtain higher grades and test scores.

You might notice that the last sentence above contains a relatively bold claim—especially the part about higher test scores. We stand by that claim because of what we know from our own teaching, as well as from research on what happens when assessment is used to provide feedback to both students and teachers. When we think about assessment as feedback, instead of just measurement, claims about improvements to teaching and learning make sense. For a content-free demonstration of how assessment as feedback can promote learning and motivation, please see the video on formative assessment produced by the Arts Achieve project in New York City: www.artsachieve.org/formative-assessment#chapter1; scroll to 8:56 on the timeline.

What About Grading?

Unlike formative feedback, summative assessment has gained a reputation for having unintended, often destructive consequences for both learning and motivation. For example, research showing that grades are negatively associated with performance, self-efficacy, and motivation implies that grades can trigger counterproductive learning processes (Butler, 1987; Butler & Nisan, 1986; Lipnevich & Smith, 2008), especially for low-achieving students. Because our grade-obsessed society is unlikely to abandon grades any time soon, the best we can do is attempt to minimize the negative influence of grades and scores on students. Formative feedback can help us do that.

Giving students grades is not formative feedback. For feedback to be formative, it occurs while students are in the process of learning, whereas grades provide a summative judgment, an evaluation of the learning that has been achieved. Unlike feedback, grades do not provide students with the information they need to take the necessary action to close the gap between their current learning status and desired goals (Sadler, 1989). Grades and scores stop the action in a classroom: Feedback keeps it moving forward.

Three Guiding Questions

Sadler (1989) and Hattie and Timperley (2007) characterize formative assessment in terms of three questions to be asked by teachers and students: Where are we going? Where are we now? Where to next? Each question elicits information and feedback that can be used to advance learning. As you will see throughout this book, these questions are the foundation for effective formative assessment; we will return to them again and again.

To illustrate how these questions are operationalized in practice, consider the following example from a visual arts unit that uses formative assessment. Notice how assessment is seamlessly integrated into the lessons in a way that enables actionable feedback for everyone at work in the room—teachers and students alike (Andrade, Hefferen, & Palma, 2014).

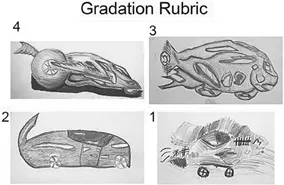

Jason Rondinelli and Emily Maddy teach art in a middle school in Brooklyn, New York. They engaged their students in a long-term biomorphic car project focused on, among other things, observational drawing, contour line drawing, and gradation value studies. As students worked on their car drawings, Emily and Jason noted that many of them needed additional instruction about gradation. This observation of student work led them to make adjustments to their instruction. After reviewing the concept of gradation and how it could be used in the project, they involved students in the formative assessment process, beginning with sharing a visual gradation rubric (Figure 1.1; see Andrade, Palma, & Hefferen, 2014, for the color version) created from other, anonymous student artwork.

Figure 1.1 Visual Gradation Rubric

In order to get students thinking about the nature of gradation—a key learning goal—Jason and Emily asked them to use the visual rubric to write a narrative gradation rubric. A rubric is typically a document that lists criteria and describes varying levels of quality, from excellent to poor, for a specific assignment. Although the format of a rubric can vary, all true rubrics have two features in common: (1) a list of criteria, or what counts in a project or assignment; and (2) gradations of quality, or descriptions of strong, middling, and problematic student work (Andrade, 2000; Brookhart, 2013). A checklist is simply a list of criteria, without descriptions of levels of quality. Jason and Emily presented the visual rubric in Figure 1.1 in order to engage their students in thinking about the nature of gradation while creating a written rubric.

In small groups, students defined a level of the rubric (4, 3, 2, or 1) by comparing their assigned rubric level to the level above or below it, describing the positive and negative uses of gradation in each of the examples, and listing descriptions of gradation at their rubric level. They were asked to describe only gradation, not other aspects of the car such as shape, color, design, or use of detail. By writing the narrative rubric, students were building disciplinary vocabulary, constructing an understanding of an important artistic concept, and answering the question, “Where are we going?”

Once the students defined and described the level assigned to their group, they combined their ideas into the rubric, illustrated in Table 1.1. The teachers then asked them to engage in formative self-assessment of the use of gradation in their drawings of cars by writing their answers to the following questions:

- Based on the gradation rubric, what is the level of your car?

- What will you do to improve the gradation of your car?

In this way, students were addressing the questions, “Where am I now?” and “Where to next?”

Their rubric was helpful in answering the “where to next?” question because it was descriptive. If it only used evaluative language such as “excellent gradation/good gradation/poor gradation,” it would not have been at all helpful to students as they revised and improved their work. Good rubrics describe rather than evaluate (Brookhart, 2013), and thereby serve the purposes of learning as well as (or even instead of) grading.

Table 1.1 Narrative Gradation Rubric

| 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

|

| + | + | + | + |

| • It has a cast shadow. • It has gradation on the bottom. • It has a light source. • It goes from light to dark very clearly. • Light colors blend in with dark. • The way the artist colored the car showed where the light source was coming from. - • It has an outline. • Cast shadow is too dark. • Doesn’t go from light to dark, doesn’t have enough gradation. • Outlined some body parts. • Cast shadow is really straight. | • It has shine marks. • Artist shows good use of dark and light values. • The picture shows gradual shades in the car. • He used light values which helped the car the way he used the shadows. - • Needs more gradual value. • Give wheels lighter gradation or darker shade. • The direction of the light is not perfectly directed. • The artists basically outlined the car. • He had more dark value than light values. • The wheels were too light . | • There is gradation on the bottom of the door. - • The car is outlined. • There is no shadow. • It’s not shaded from light to dark. • There are no details. • The windows have no shine marks. • The wheels do not look 3-D. | • The rims are shaded... |