eBook - ePub

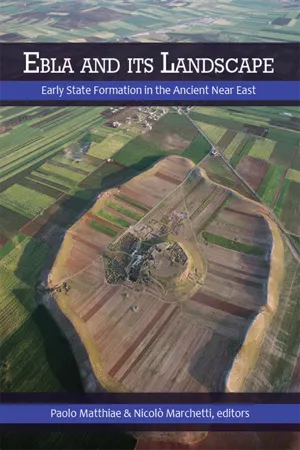

Ebla and its Landscape

Early State Formation in the Ancient Near East

- 563 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Ebla and its Landscape

Early State Formation in the Ancient Near East

About this book

The discovery of 17,000 tablets at the mid-third millennium BC site of Ebla in Syria has revolutionized the study of the ancient Near East. This is the first major English-language volume describing the multidisciplinary archaeological research at Ebla. Using an innovative regional landscape approach, the 29 contributions to this expansive volume examine Ebla in its regional context through lenses of archaeological, textual, archaeobiological, archaeometric, geomorphological, and remote sensing analysis. In doing so, they are able to provide us with a detailed picture of the constituent elements and trajectories of early state development at Ebla, essential to those studying the ancient Near East and to other archaeologists, historians, anthropologists, and linguists. This work was made possible by an IDEAS grant from the European Research Council.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ebla and its Landscape by Paolo Matthiae, Nicoló Marchetti, Paolo Matthiae,Nicoló Marchetti in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART 1

Town Archaeology

CHAPTER 1

A LONG JOURNEY

Fifty Years of Research on the Bronze Age at Tell Mardikh/Ebla

The archaeological exploration of Tell Mardikh began in 1964 using a critical perspective characterized by the most advanced and mature techniques of Oriental archaeology set within a historical setting.1 It aimed at throwing some light on a number of problems of historical interpretation, begun in 1955 with the publication of the final report on the excavations at Tell Atchana, ancient Alalakh, by C.L. Woolley, which drew the scientific world’s attention in a totally different way to the possibility that the culture of Western Syria in the Aleppo region had played a primary role in the historical development of the ancient Near East as shown from the results of excavations for the phases of Middle Bronze I-II (ca. 2000–1600 B.C.) and Late Bronze I-II (ca. 1600–1200 B.C.). In particular, themes for new researches and interpretations were opened, to be verified by means of following excavations:

1. The existence of an autonomous culture of Western Syria during the first half of the second millennium B.C., independent from the Mesopotamian and Anatolian worlds;

2. Its originality and importance in the architectural, figurative, and material cultures during the whole second millennium B.C.;

3. The continuity of this culture between MB I-II, Iron Age I (ca. 1200–900 B.C.), and IA-II (ca. 900–720 B.C.);

4. The possibility of tracing back the roots of this culture in the different phases of Early Bronze I-IV (ca. 3000–2000 B.C.), and especially in the second half of the third millennium B.C.

These debates about the existence of an autonomous culture of inner Syria—from east to west between the Euphrates and the mountains extending to the north into the chains of Lebanon and anti-Lebanon, and from north to south between the Taurus Mountains and the Syro-Arabic desert south of Homs—led, between 1954 and 1962, to the publication of some articles about the figurative culture of glyptics (particularly by Strommenger and Moortgat-Correns), about architectural culture (by Frankfort), and an essay about artistic traditions (by Matthiae). On the basis of these appraisals, the term Old Syrian was adopted, with a deliberate and evident parallelism with the term Old Babylonian for southern Mesopotamia, in order to define the culture of the western Syrian world of the MB I-II and make a clear statement about the autonomy and originality of that culture. This definition was adopted also in different, albeit synthetic, contributions by Porada and Kantor, with particular regard to glyptics.

From the ambitious perspective of studying in depth not only one or the other problem just mentioned, but rather all of them, the site of Tell Mardikh looked quite interesting and extremely promising. The site (Figure 1.1) is located nearly 55 km south of Aleppo and was quite ignored until 1962, when Matthiae visited it. It had been previously visited a few times by Ingholt in 1936 and by Moortgat and Hrouda in 1955, among others. Albright stopped nearby but was unable to visit it during a trip from Jerusalem to Baghdad in 1926, after which he wrongly presumed he could identify Ebla with Tell Bia, which is really ancient Tuttul, and correctly identified Tell Hariri with Mari. The reasons this site looked interesting and promising are three: it is very large, nearly 56 ha in area, which pointed to an urban centre particularly important from the political point of view; its main occupation phases, on the basis of the surface pottery, ran approximately between the mid-third and the mid-second millennium B.C.; and a basalt basin carved on three faces was discovered on its surface around 1955—which I could later date to the nineteenth century B.C., the full MB I period—and was carried to the Aleppo Museum.

These three reasons seemed to guarantee that Tell Mardikh might effectively yield final proof of the existence of an autonomous original Old Syrian culture, first identified at Alalakh; that it might lead to the recovery of elements allowing the reconstruction of a continuity with the later phases of the history of Syria; and, most of all, that it might reveal basic evidence of the roots of Old Syrian culture in the second half of the third millennium B.C. When the systematic excavation of Tell Mardikh began, in 1968 (Figure 1.2) a basalt statue fragment was discovered bearing a royal cuneiform inscription of a certain Ibbit-Lim, king of Ebla, dating from the twentieth century B.C., which allowed us to identify the site with ancient Ebla (Figure 1.3). So much information has come from the site since 1975 that Matthiae was able to propose calling the period of EB I-IV “Early Syrian,” to confirm the designation of Old Syrian for the period of MB I-II, and to introduce the terms “Middle Syrian” and “Late Syrian” for the LBI-II and IA I-II respectively.

The configuration of the site of Tell Mardikh is quite typical of the great fortified urban settlements of the Bronze Age, but not common in inner Syria. It is characterized by an acropolis, located approximately in the middle, marked by a low hill slightly higher than the rest of the tell, surrounded by a large ring-shaped lower town on every side and by a marked peripheral rise, which, looking like a continuous ridge with a strong, nearly continuous, elevation around the whole town, separates it from the surrounding country. These three topographical sectors, still very clearly visible on the terrain, correspond to the fortified citadel, including the large royal public buildings; to the Lower Town, including most of the other public and cult public buildings and the quarters of domestic units; and to the huge rampart city walls surrounding the whole urban centre in the great town of the classical Old Syrian period, which was finally destroyed in the years around 1600 B.C.

When in 1964 the Italian Archaeological Expedition to Syria started the excavations at Tell Mardikh, during the first year the first soundings were made, by means of limited trenches, on the west side of the acropolis (Area D), in two regions of the Lower Town southwest, close to each other (Areas B and C), and on the slope of the most marked opening to the southwest in the high ramparts surrounding the urban centre, which, as it seems quite likely, might be a city gate (Area A). Since the second year, some important monuments of the great town of the beginning of the second millennium B.C. were brought to light with these soundings, including the Temple of Ishtar on the Citadel (Area D) (Figure 1.4), the Temple of Rashap (Area B) in the Lower Town southwest, and Damascus Gate (Area A). The excavations were carried out in yearly campaigns, and during the first decade, up to 1973, they identified and brought to light, sometimes only in part, several other very important buildings of the same archaic (MB I) and classical (MB II) Old Syrian periods, between 2000 and 1600 B.C., like the Temple of Shamash (Area N) in the Lower Town north, the Sanctuary of Royal Ancestors (sector B South), and, most importantly, the Royal Palace E (Area E), albeit for a small part, and the Fortress (Area M) on the southeast side of the town walls.

The second decade of excavation activities started in 1974 with the identification on the southwestern slopes of the acropolis of Royal Palace G (Area G), of the high Early Syrian period (EB IVA), between 2400 and 2300 B.C. (Figure 0.6) This period is marked by the crucial discovery in 1975 of the famous State Archives (Figures 1.5, 1.6), whose excavation was completed in 1976. During the same decade, while different sectors of the great complex of the Early Syrian Royal Palace G were being explored, including the Administrative Quarter, the Southern Quarter, and the South and West Units of the Central Complex, the systematic exploration of the later classical Old Syrian Ebla started in the Lower Town west, with the identification and excavation of the extended Western Palace (Area Q) and of three important tombs, partially violated, of the Royal Necropolis stretching below it.

During the third decade of systematic exploration, most of the important Old Syrian monuments of the Lower Town were brought to light, including the Northern Palace (sector P North), Sacred Area of Ishtar with Temple P2 (sector P Centre), the Cultic Terrace (sector P South), and the Archaic Palace (sector P North) founded in the late Early Syrian period (EB IVB), an antecedent of the Northern Palace from MB II (Figure 1.7). At the same time, on the acropolis the site of at least one royal tomb was identified, dating to the Archives period, but completely sacked or never employed (Area G West). In 1984, a limited sector of Building G2 (Area G South) of the archaic Early Syrian period (EB III, around the mid-third millennium B.C.) was also brought to light.

During the fourth decade of excavations, the greatest attention was given to the rampart fortifications of the archaic and classical Old Syrian town, with the exploration of the Western Fort (Area V), the Northern Fort (Area AA), the Euphrates Gate (Area BB), Aleppo Gate (Area DD), the peripheral residential quarters (Area Z), and the quarters close to the citadel (sector B East). The research activities in the Lower Town, which mark the fifth decade until 2008, yielded some important complements to the excavation of Royal Palace G, but also allowed the discovery of the Southern Palace (Area FF) (Figure 1.8), the recovery of a complete quarter of private houses of the classical Old Syrian period quite well preserved (sector B East), and, most of all, starting in 2004, the identification, in the Lower Town southeast, of the great Temple of the Rock (Area HH), of the high Early Syrian period (Plate 4:1), with the first well-preserved remains of the late Early Syrian town of the last centuries of the third millennium B.C. Research on the Acropolis was resumed during the second half of the fifth decade, until 2010, and produced a very important result with the identification of the high Early Syrian Red Temple (Area D) in the western region of the central hill. The same period was marked by the beginning of the systematic exploration of Royal Palace E of the Old Syrian period, reemployed during the early Middle Syrian period (LB I). Due to ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

- INTRODUCTION. Representing the Chora of Ebla

- PART 1. TOWN ARCHAEOLOGY

- PART 2. REGIONAL ARCHAEOLOGY

- PART 3. TEXTUAL EVIDENCE

- PART 4. GEOMORPHOLOGY AND REMOTE SENSING

- PART 5. ARCHAEOMETRY AND BIOARCHAEOLOGY

- CONCLUSIONS. In Search of an Explanatory Model for the Early Syrian State of Ebla

- ABBREVIATIONS

- REFERENCES

- INDEX

- ABOUT THE AUTHORS

- COLOUR PLATES