eBook - ePub

New Demographics New Workspace

Office Design for the Changing Workforce

- 164 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

New Demographics New Workspace

Office Design for the Changing Workforce

About this book

Offices shape the lives of millions of people. How we plan, design and equip them says a great deal about the culture of organisations, the mentality of managers and the motivations of staff. But getting the right balance between management efficiency and individual wellbeing is as elusive as ever. New Demographics New Workspace looks for answers in some new places. The authors address ways in which the office environment can be redesigned to offer greater levels of comfort, flexibility and fitness for purpose in the new age of the older knowledge worker. Based on the findings of the authors 'Welcoming Workplace' research project at the Royal College of Art Helen Hamlyn Centre, New Demographics New Workspace examines the impact of two of the most significant shifts in the workplace: the ageing of the workforce and the changing nature of work itself in the knowledge economy. By examining the movements and motivations of older knowledge workers in the UK, Japan and Australia, the authors have generated new conceptual approaches to office design that offer an alternative to the current outdated model derived from the factory floor. In particular they question the value of open-plan offices that favour collaboration over concentration and contemplation. Given the growing pensions crisis and anticipated knowledge gap in the workforce in many developed countries, this book has real political, economic and social resonance. If we are all going to have extended working lives in the 21st century, the places in which we work will need to flex and adapt to make us want to keep on working.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access New Demographics New Workspace by Jeremy Myerson,Jo-Anne Bichard in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

Reviewing the context

‘What has not sunk in is that a growing number of older people … will participate in the labour force in many new and different ways’

1

The change we face

An older and wiser workforce will steer the future economy

In the early years of the twenty-first century, the world of work in general, but office work in particular, stands on the brink of transformational change. The skills and qualifications of the workforce, the patterns of working, the technologies and systems in use, the design of places and spaces for work, and the rewards in retirement after work – all of these things are under review at a time of unforeseen instability in global financial markets.

Such dramatic shifts are not unprecedented. Exactly 100 years ago, the workplace was transformed by a series of new industrial technologies, among them the typewriter, telephone, elevator, electric light bulb and adding machine, which helped to create a new environment for working and shaped the template for office life in the twentieth century. Indeed the history of work has been driven by technological change from the spinning jenny to the silicon chip.

The change we face today once again has new technologies at its core – these are the information technologies of the Internet, which are forcing nearly all organisations to rethink and regroup, and accompanying digital devices which make remote and mobile working more feasible. But this time there are crucial differences that suggest social and demographic change rather than technological advance will be the dominant factor in comprehensively reshaping employment and the workplace.

This is because the average age of the twenty-first century workforce will be older than at any time in human history and because the nature of the work these employees will be doing in offices will be more closely related to the production and distribution of knowledge than the production and distribution of goods and services, therefore requiring more emphasis on the individual’s know-how, learning and expertise.

A different workplace

The combination of a changing age profile in the workforce and the changing nature of work tasks in the knowledge economy, demanding a higher level of skill and experience, leads the authors of this book to the view that a different type of workplace will be required to accommodate a changing workforce. In place of the paper-shifting office that emerged in the early twentieth century, modelled on the time-and-motion studies of factory floor and geared to the dominant economic model of Taylorism (after Frederick Taylor), one can foresee a new, digitally-driven type of workplace that is more flexible in use of time and space, more welcoming to its workforce, more tolerant of the frailties of ageing and more geared to the needs of knowledge interactions.

In formulating ideas and plans for this new workplace, it can be argued that the study of demographic trends, which can be predicted with a measure of accuracy and confidence, provides a more stable basis to plan for change than either technological trends, which tend to be uneven in their adoption by office-based organisations, or economic ones which currently baffle the brightest minds. It is instructive to recall how few economic commentators were able to predict the global banking crisis before autumn 2008.

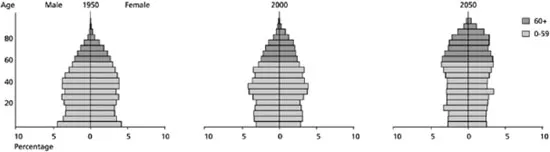

In contrast, demographics have a clear-cut, profound and entirely predictable impact on the workplace. We know that population ageing is a worldwide phenomenon due to falling fertility rates, better healthcare and nutrition, early childhood immunisation and improving survival rates from chronic diseases such as cancer. We know that the share of older people over 65 is increasing almost everywhere and that the pensions provision for those retiring from the workplace has been badly damaged by the effect of plummeting share prices on pension funds.

While we enjoy the prospect of longer lives, pushing the limits of human longevity ever upwards, we also know that the ratio of potential workers (aged 15–64) to the over-65s is declining rapidly. This leaves governments worldwide with a major headache in figuring out how to pay for the welfare costs of the elderly with a shrinking workforce in a fiercely competitive global economy. Japan and Europe have the fastest ageing populations – nearly one-third of Japanese citizens will be over 65 by 2030 while one in two European adults of working age will be over the age of 50 by 2020 – but other nations face the same frightening demographic curve.

The scale of the economic challenge to national wealth and prosperity posed by population ageing is unprecedented and exacerbated by corporate early-retirement policies, which have culled a whole generation of older workers, and there are no prior employment models on which to lean. Labour supply shortfalls in previous eras were answered by admitting wider social groups into the workforce, either women or people from outside the nation state. Women are now an established part of the workforce and can no longer be seen as an untapped resource. Immigration meanwhile is still widely regarded as part of the economic answer to a shrinking workforce; within Europe, Spain has managed the highest levels of immigration to meet labour shortages head on. But more economic migrants must today show evidence of qualifications and training as governments calibrate immigration policy more tightly to the needs of the knowledge economy.

Knowledge to the fore

Why have knowledge and information come to the fore so strongly in thinking about the workplace? This is because the new workplace is set to run on creativity and brainpower, not engineering-led processes, and must take its organisational cues from that realisation. Much of the repetitive process work that once occupied large numbers of staff in offices within developed economies is today already handled by computers or sent offshore to lower-cost economies. More organisational time and effort is being spent on what is known as ‘knowledge work’. This type of work depends not so much on formula and process, working to a set script within a supervised hierarchy, but on independently applying formal knowledge and learning as part of a culture of collaboration, initiative and innovation.

Knowledge workers present new challenges to how work should be organised. Many sit outside the formal hierarchies of their organisations and work on projects to their own individual timetables, setting their own deadlines and targets. They tend to be self-motivated and reliant on their own experience and expertise to undertake special-assignment or consulting work for their own employers. Clocking on to nine-to-five regimes hold little meaning for them.

Research suggests that knowledge workers identify themselves more with their professional discipline and specialism and less with their employer or place of work. They expect to work in a variety of situations and for a number of employers over their working life. The constant is their knowledge, which they want to keep updated. They require a stronger element of trust and individual control in the workplace and take more personal responsibility for the results of their work. Many knowledge workers are also de facto older workers because they have acquired their knowledge and expertise over the course of a long career.

Here two trends collide. The classic, instinctive answer for governments facing a combination of a shrinking workforce and rising age-related welfare costs is to encourage a deferment of retirement – to engineer an extension to working lives in order to plug the knowledge gap with older workers who have gained and honed the necessary know-how over time. Employers who are dismayed to see the ‘corporate memory’ of the organisation drain away with every retirement party are supportive of such moves, because they are increasingly interested in retaining knowledge and experience within their businesses.

It is not difficult therefore to envisage, in the early decades of the twenty-first century, growing numbers of older office workers who will not retire at the expected age but will remain at work for longer, many of them on a consultancy, special-project or part-time basis. But to encourage such well-qualified, mature staff to choose to stay on after the normal retirement age requires the emergence of a different type of workplace – one in which the design of jobs, work processes, management structures and institutional attitudes to ageing are radically rethought.

Office design as a priority

Some of this is already underway, but it is an inescapable fact that none of the important cultural, contractual or human resource changes envisaged will really count unless a redesign of the physical office setting is given priority within organisational change as an obvious lever for transformation. One needs to consider a redesign of the office environment itself, especially as older knowledge workers are likely to be compromised in the work environment by the inevitable effects of ageing on vision, hearing, posture, memory, balance, muscular strength, dexterity and so on.

Here we reach the central theme this book aims to discuss. If an older and wiser workforce is set to steer the future economy, bridging the talent gap in key areas of knowledge work, what are the optimum workplace design considerations for this changing workforce to succeed? We know that the scientifically managed, one-size-fits-all office environment of the twentieth century neither fits the more unstructured, experiential demands of knowledge work, nor addresses the needs and aspirations of an ageing workforce. But we are struggling to give design shape and form to the new workplace that could replace it.

The picture is complex. It is now possible to walk into an office almost anywhere in the world and find up to four generations at their desks in one space. Any new solutions must therefore accommodate not just the baby boomers but younger colleagues too within an inclusive framework. In the following chapters we examine the contexts for ageing and for knowledge work. The scale of the change we face demands we start finding the right design solutions right now.

2

The greying workforce

Throw a stone in the workplace and you’ll hit a senior

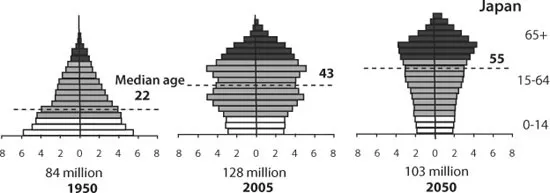

To see a workforce greying before your eyes, look east. Creaking under the weight of its own success in boosting longevity, Japan has the world’s fastest ageing population. A quarter of its citizens are now aged 65 and over. In less than one lifetime Japan has shifted from a country with a young population to the one with the highest proportion of older people. In 1950 the median age of the Japanese population was just 22 – by 2005 this had climbed to 43. In 2050 the average age will be 55. As a consequence, Japan expects its workforce to shrink by 16 per cent in the next 25 years. Little wonder that when a senior figure in Tokyo’s Building Research Institute presented his country’s demographic picture, he said simply: ‘If you throw a stone in Japan, it will hit a senior.’

Japan’s response to this demographic shift has been to encourage older workers to stay in employment for longer. Previously its system of retirement or teinen (literally ‘prescribed year’) designated retirement at the age of 55. On reaching this age, many people (especially men) continued working, many with the company they had been with all their working life. However, in many cases teinen meant working at a lower level and with a resulting loss of status and income.

In the 1980s, in response to the growing ageing population, the Japanese Government raised the age of teinen to 60, and created ‘silver talent centres’ in major cities as places where older workers could find employment as well as help with financial concerns. Yet many of the seniors seeking work tended to be educated ‘white-collar’ workers who were considered overqualified for the menial jobs generally offered to older people, such as cleaning parks or guarding bicycles at train stations.

Today, as the economic position tightens further, Japan is looking to raise its pension payout age from 60 to 65. It may have the most rapidly ageing population but it is not the only nation taking action as a declining workforce puts a strain on public and corporate pensions. In the UK, there has been agitation to raise the official retirement age from 65 to 67 while defined benefit pension schemes are facing closure. A similar picture is emerging in the United States where there are plans to raise the social security retirement age.

Governments around the world have little choice but to consider such actions to avoid taking a massive financial hit in the context of population ageing. In 2008, according to the Stanford Longevity Center, average life expectancy at birth was 82 in Japan, 79 in the UK and 78 in the US. By 2050, it will be 87 in Japan, 84 in the UK and 83 in the US. Worldwide, life expectancy will rise from 67 in 2008 to 75 in 2050 and the percentage of over-60s in the global population will double from 11 per cent to 22 per cent. By 2050, Japan will have greyed to the extent of having 44 per cent of its population over 60, but the UK won’t be that far behind: 30 per cent will be over the age of 60.

United Nations population pyramids for the UK showing the projected population bulge in the over 60s (United Nations, 2002)

United Nations population pyramids for Japan showing rise in median age (United Nations Revised Stanford Longevity Centre, 2006)

Britain’s demographic change

Britain’s changing demographics are eye-catching. Pensioners now total 11.5 million, nearly a fifth of the UK population. We have just passed a milestone which means that, for the first time since records began, the number of people of pensionable age (60 for women and 65 for men) exceeds the number of children under 16. This landmark announcement made by the Office of National Statistics in August 2008 sent the media into an immediate flurry, searching for experts to explain what it all meant. Mervyn Kohler, Head of Public Affairs at charity Help the Aged, cogently explained in The Independent: ‘The days of assuming older people are dependants must now come to an end. These figures clearly show the economic harm that will be caused to UK plc by continuing to exclude older people from the active workforce.’

In the same article, business leaders warned that an increase in life expectancy, coupled with the fact that 12 million Britons have not saved enough for retirement, means there is a need to ensure people work beyond the retirement age. Neil Carberry, Head of Employment Policy at the Confederation of British Industry, said: ‘As the baby-boom generation retires we are likely to see significant increases in the ratio of retired people in the workforce. We are going to see many people will choose to work longer.’

The age-balance of Britain’s workforce has in fact been changing for some time, as the first batch of baby boomers reach retirement age. In some highly skilled areas such as aerospace and defence, up to 40 per cent of the workforce could be leaving in the next five years in line with international trends, according to The Economist, taking a lifetime of expertise with them. Professional body City & Guilds has also predicted that from 2010, the number of young people reaching working age will fall by 60,000 every year.

Further predictions estimate that between 2010 and 2020, the UK will need more than two million new workforce entrants. It is now widely acknowledged that this demand can only be met through a combination of most adults extending their working life and enticing many more to re-enter the labour market. Whilst the scales have already been tipped in the UK with pensioners now outnumbering children, in the next decade it is predicted that there will be more people aged over 40 than under 40.

Advances in medical care and greater awareness of health and diet have made a key impact, so much so that the fastest growing age group in Britain are the over-80s who now number 2.7 million, more than five per cent of the population. In line with a falling mortality rate and increased life expectancy, there has also been a significant drop in fertility rates to 1.73 births per woman, which is below the general population replacement level of 2.1 births per woman.

All of this has resulted in what researchers call a ‘deteriorating dependency ratio’ where there is a higher percentage of people who are economically inactive yet are supported by a workforce that is both shrinking and ageing. A ‘demographic time bomb’ of this t...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- About the Authors

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- Part One Reviewing the context

- Part Two Rethinking the culture

- Part Three Redesigning the environment

- References

- Index