- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Archaeology of the Southwest

About this book

The long-awaited third edition of this well-known textbook continues to be the go-to text and reference for anyone interested in Southwest archaeology. It provides a comprehensive summary of the major themes and topics central to modern interpretation and practice. More concise, accessible, and student-friendly, the Third Edition offers students the latest in current research, debates, and topical syntheses as well as increased coverage of Paleoindian and Archaic periods and the Casas Grandes phenomenon. It remains the perfect text for courses on Southwest archaeology at the advanced undergraduate and graduate levels and is an ideal resource book for the Southwest researchers' bookshelf and for interested general readers.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Archaeology of the Southwest by Linda S Cordell,Maxine McBrinn,Maxine E. McBrinn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Place and Its Peoples

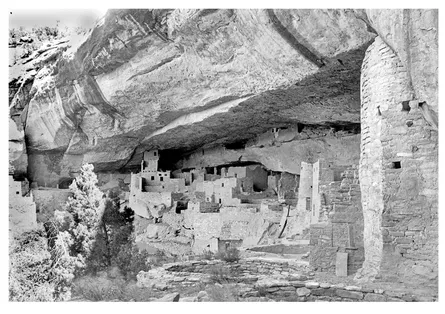

The American Southwest is a vast region of contrasts and diversity. Its physical landscapes include forested mountains, mesas (tablelands) dotted with sparse vegetation, and expanses of desert concealing lush streamside oases. Some mesas are made of layers of sandstone and shale. Weathering of the softer sandstones can create caves and rock-shelters in which some Native American ancestors built their homes, including the cliff dwellings of Mesa Verde, Colorado (Figure 1.1). Seeps may develop at the contact zone between softer sandstones and harder shale, providing water within the rock overhang. All of the Southwest is dry, its weather unpredictable, and water its most critical resource. Despite the harsh climate, Native peoples of the Southwest have been successful farmers for millennia, relying on crops indigenous to the Americas, principally corn, beans, and squash.

FIGURE 1.1. Cliff Palace, Mesa Verde, Colorado, was built by ancestors of modern Pueblo Indian peoples, in about 1200 CE, yet many of the walls are still standing. More than half a million people visit Mesa Verde National Park each year, and many of them have the opportunity to walk through rooms that were last occupied more than 800 years ago. (Courtesy of the University of Colorado Museum)

Within the contiguous United States, the Southwest is home to the largest number of Native peoples who continue to occupy their original homelands and retain their languages, customs, beliefs, and values while participating fully in twenty-first-century life. It is a tribute to them that despite incursions by Europeans, religious persecution, racial prejudice, and periods of forced acculturation, so much of their native culture remains intact. The deep history of people of the Southwest, their skill at wresting a living in a beautiful but inhospitable land, and the resilience of their ways of life through the centuries offer us opportunities to begin to understand some problems of concern to all peoples today—for example, how to sustain our food supply over the long term despite challenges of adverse weather and unpredictable climate, and how to preserve diversity within human society as a whole so that important reservoirs of traditional knowledge are not lost.

Different perspectives are available to understand any region. Appreciation and knowledge may derive from a regions art, botany, ecology, geology, history, hydrology, literature, and zoology. The American Southwest has been studied and portrayed in all of these ways. We explore the American Southwest through archaeology. Archaeology as it is practiced in the region today makes use of many other sources of information, such as those just listed. It also includes a variety of techniques and frames of reference that allow following processes of change—as well as stability—over the long term. Many of those special techniques were in fact developed in the American Southwest. For example, through the study of tree rings from living southwestern trees and timbers from ancient southwestern ruins, archaeologists learned ways to determine when, in calendar years, the roof timbers were cut and eventually to estimate how much rainfall occurred over the years—centuries ago—when the trees grew (see chapter 2). Other archaeological techniques that were developed though not invented in the Southwest are invalidating Euroamerican myths about indigenous social networks, exchange, and gender roles and therefore extending our understanding of traditional knowledge. For example, most people even today believe that, among the indigenous peoples of the Southwest, making pottery vessels was a household craft and that every woman made such containers for her family. In the 1930s, archaeologist Anna O. Shepard applied optical petrography (using a special microscope to identify the minerals inside the pottery fabric) to ancient southwestern pottery. She discovered that pottery assumed to have been made at the ancient village where it was eventually excavated had in fact been made elsewhere—in large quantities—and exchanged over very long distances well before there were European or American means of transport, such as horses and cars. Her discoveries suggested that at some times and places, southwestern potters produced much more pottery than they needed for their households and that social networks were much larger than had been thought (see chapter 3).

As we write in 2011, a tremendous amount of archaeological work is being done in the Southwest—estimated at many millions of dollars annually—involving hundreds of professional and avocational archaeologists and using a variety of both low-tech (trowels and shovels) and high-tech (laser-enhanced imagery and isotope analyses) tools. New information is accumulating rapidly and changing our perspectives on the southwestern past. We believe that this effort provides all of us with an important example of human endeavor over the long term and clearer insight into one aspect of the trajectory of human history. The information that comes from archaeology however, is very different from that which comes from history—written or oral. Archaeology deals with tangible remains from the past—artifacts and the contexts in which they are found. These may yield specific information about some things, such as the particular mountain from which stone was taken to make a spear point, and no information at all about others, such as the name of the hunter who used the spear or what language she or he spoke. A great deal of archaeology is not so much about what we find, but how we use the artifacts and their associations to answer the questions we have. The questions archaeologists ask, as well as the answers, have changed over the years as archaeology has grown as a discipline.

In this chapter, we introduce the region, its indigenous peoples, and the names by which archaeologists refer to their ancestors. In chapter 2, we outline the natural environments of the Southwest and describe the tools with which archaeologists learn what those environments were like in the past. Chapter 3 describes the development of archaeological research in the Southwest. It focuses on the concepts archaeologists use to organize their observations. These include some essential tools of vocabulary and classification as well as discussion of how archaeology itself has grown and changed as a field of study. These three chapters together can be thought of as an introductory unit.

The subsequent chapters follow southwestern peoples over the course of about 14,000 years. Rather than presenting a simple chronicle of events and developments, we explore the dynamic behaviors that archaeologists infer from the tangible remains they study, and how those archaeological inferences are made.

Concepts and Boundaries

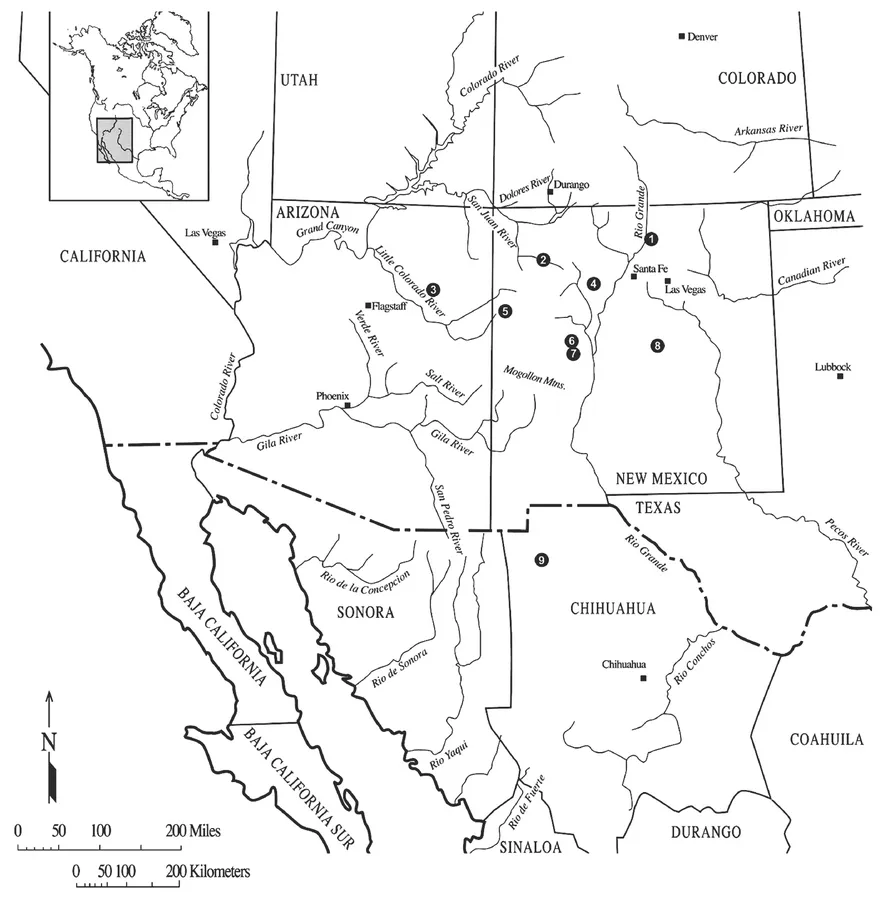

The North American Southwest is a culture area, a geographical region inhabited by Native peoples who shared similar ways of life by virtue of their histories of interaction with one another and their adaptation to the natural environment (Kroeber 1939). Precise boundaries for any culture area are usually difficult to specify, and they change over time. Archaeologist Erik Reed famously described the Southwest as extending from Durango, Mexico, to Durango, Colorado, and from Las Vegas, New Mexico, to Las Vegas, Nevada (Figure 1.2). Generally, the Southwest culture area includes all of Arizona, most of New Mexico, large parts of Colorado and Utah, and a small portion of Nevada in the United States, and all of the states of Chihuahua, Sonora, and Sinaloa in Mexico. The region really is southwest only as seen from the eastern United States. From the perspective of Mexico City, it is northwest. Because of this ambiguity, some researchers have proposed alternative names for the region, such as "Oasis America" and "Gran Chichimeca" (Braniff 2001; Daifuku 1952; Fowler 2000; Reed 1964), but so far none has caught on.

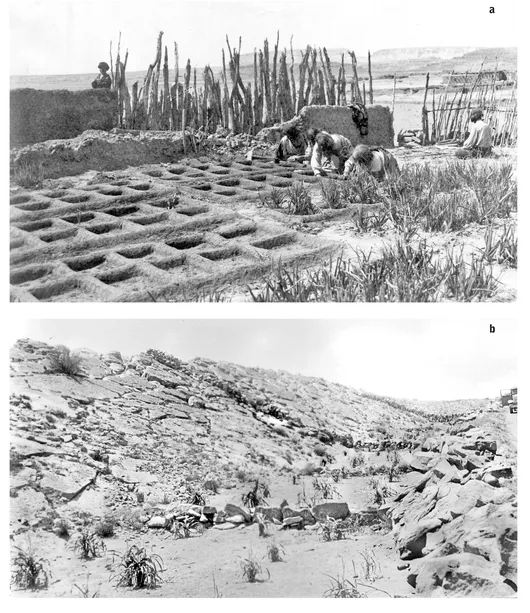

From about the beginning of the common era to the mid-sixteenth century, southwestern Native peoples lived by cultivating corn, beans, and squash, gathering wild plant foods, and hunting. Most of them lived in one place during all or most of the year, displaying the archaeological hallmarks of sedentary peoples: permanent architecture and ceramic containers for cooking and storage. They developed ingenious techniques for conserving moisture and cultivating the earth (Figure 1.3) and built some of the most enduring and spectacular architectural structures in North America. The cliff dwellings of Mesa Verde in Colorado and Canyon de Chelly, Arizona; the formal, multistory stone towns

FIGURE 1.2. The Southwest culture area, which includes portions of the United States and Mexico, with map showing locations of sites discussed in this chapter. (Map by David Underwood, inset by Charles M. Carrillo) LEGEND:

1. Taos

2. Chaco Canyon

3. Hopi

4. Jemez

5. Zuni

6. Laguna

7. Acoma

8. Bosque Redondo (Fort Sumner)

9. Casas Grandes (Paquimé)

FIGURE 1.3. Gardens such as these are among the many ingenious techniques Native southwestern peoples use to conserve moisture for agriculture. (a) Waffle garden, Zuni Pueblo, New Mexico. (Photo by Jesse Nusbaum, ca. 1910. Courtesy of the Museum of New Mexico). (b) Hopi garden with check dams, planted in corn. (1931 photo, Courtesy of the University of Colorado Museum of Natural History)

of Chaco Canyon, New Mexico; and the massive adobe buildings, effigy mounds, and ball courts of Casas Grandes (also called Paquimé) in Chihuahua are treasures of world heritage today. These places are also respected footprints of the ancestors of contemporary Native peoples.

Topographically, the Southwest encompasses the low basins of the Sonoran Desert; the higher, sparsely wooded mesas of the Colorado Plateaus; and the still-higher, wooded and forested mountain masses of central Arizona, New Mexico, and Chihuahua. Elevations range from near sea level in the basins to just above 4,000 meters (13,000 feet) in the southern Rocky Mountains. Uniting all these diverse landscapes is the regions arid climate. Ephemeral streams and internal drainage characterize much of the land surface. The major rivers are the Colorado, San Juan, Rio Grande, and Pecos.

Agriculture sets the Native peoples of the Southwest apart from the gathering-hunting-fishing peoples of California and the Great Basin, on the west, and from the bison hunters of the Great Plains, on the east. The southern boundary of the Southwest is more difficult to define, because precolumbian peoples of Mesoamerica farmed essentially the same crops as their northern neighbors. Anthropologists set the Southwest and Mesoamerica apart largely because, over time, the peoples within each of these regions interacted more intensively with one another than they did with those in other regions. Throughout Native American history, boundaries between the Southwest and its neighboring culture areas were defined more clearly at some times than at others. There were periods when some southwestern peoples hunted bison on the southern Plains, lived by foraging rather than farming, and traded with, visited, and perhaps fought for or against Mesoamerican states.

Yet a core of ways of doing things, recorded by historians and ethnographers and inferred by archaeologists from patterns of material culture, set the peoples of the Southwest apart. These generally include maize agriculture; the use of digging sticks, flat metates (grinding stones), manos (hand stones) (see Figure 6.1, Chapter 6), and finely made pottery; and the construction of compact, multiroom villages (pueblos) in some places and dispersed settlements (rancheíras) in others. At times, groups developed social institutions that united several villages or communities and constructed elaborate centers with unique forms of public architecture—though without systems of writing or densely inhabited urban areas like those characterizing the Mayan and Mexíca societies of Mesoamerica. A central concern in southwestern archaeology and in this book is that of exploring archaeological evidence for the changing social networks of interaction that define the Southwest over time.

The Southwest’s Spanish Colonial History

Understanding the Southwest today requires knowledge of its sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Spanish colonial history. Even before English colonists founded Jamestown in eastern North America in 1607, Spain began to explore and colonize the Southwest, sending out its first expeditions from what is now Mexico in 1539 and 1540 (Table 1.1). For three centuries, the Spanish language and Spanish customs prevailed in the Southwest, where they continue to be influential today. Indigenous peoples were described not from an English perspective but from an Iberian viewpoint influenced by Spaniards' experiences with Native peoples in central Mexico and the Caribbean.

Spaniards expanded into the Southwest from two directions, at different times. Initially, exploration and colonization were launched from central Mexico into present-day central New Mexico. The secular impetus for this invasion was Spain's desire for mineral wealth and the colonists' desire for land and Na

Table 1.1. Key dates in the history of the Southwest heartland

| 1539 | Fray Marco de Niza expedition to Zuni, where the Moorish slave Esteban de Durantes was killed |

| 1540-1542 | Francisco Vásquez de Coronado expedition to Zuni, the Tiguex pueblos, Pecos, Taos, and the Great Plains; Battle of Hawikku; Pedro de Tovar to the Hopi pueblos |

| 1581 | Fray Augustín Rodriguez and Captain Francisco Chamuscado expedition up the Rio Grande to the Rio Grande pueblos, to Zuni, the Galisteo Basin, and the Plains |

| 1582 | Antonio de Espejo expedition to Piro pueblos, Acoma, and Querecho |

| 1590 | Gaspar Castaño de Sosa expedition to Pecos, Picuris, and Santo Domingo |

| 1598-1599 | Juan de Oñate’s conquest of New Mexico |

| 1598 | First Spanish colony at San Gabriel del Yunque (near Ohkay Owingeh); New Mexico declared a missionary province of the Franciscan order; rebell... |

Table of contents

- Cover

- Original Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- LIST OF TABLES AND ILLUSTRATION

- PREFACE

- CHAPTER I. THE PLACE AND ITS PEOPLES

- CHAPTER 2. NATURAL ENVIRONMENTS OF THE CULTURAL SOUTHWEST

- CHAPTER 3. TOOLS FOR DIGGING INTO THE PAST

- CHAPTER 4. THE FIRST SOUTHWESTERNERS—PALEOINDIAN AND EARLY ARCHAIC ARCHAEOLOGY

- CHAPTER 5. TRANSITIONS TO AGRICULTURE, 2100 BCE-200 CE

- CHAPTER 6. SETTLEMENTS, FARMING, AND INCREASING DIVERSITY, 200-900 CE

- CHAPTER 7. SOCIAL AND POLITICAL ORGANIZATION, 900-1250 CE

- CHAPTER 8. MOVEMENT AND CHANGE DURING TURBULENT TIMES, 1150-1400 CE

- CHAPTER 9. COMING TOGETHER, MAKING COMMUNITIES, 1275-1490 CE

- CHAPTER 10. TRANSITIONS, RESISTANCE, ACCOMMODATIONS, AND LESSONS, 1500-1900 CE

- CHAPTER 11. LOOKING TO THE FUTURE

- REFERENCES

- INDEX

- ABOUT THE AUTHORS