- 235 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

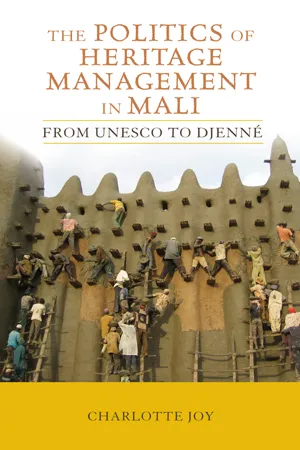

The UNESCO World Heritage Site of Djenné, in modern day Mali, is exalted as an enduring wonder of the ancient African world by archaeologists, anthropologists, state officials, architects and travel writers. In this revealing study, the author critically examines how the politics of heritage management, conservation, and authenticity play essential roles in the construction of Djenné's past and its appropriation for contemporary purposes. Despite its great renown, the majority of local residents remain desperately poor. And while most are proud of their cultural heritage, they are often troubled by the limitations it places on their day to day living conditions. Joy argues for a more critical understanding of this paradox and urges us all to reconsider the moral and philosophical questions surrounding the ways in which we use the past in the present.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Politics of Heritage Management in Mali by Charlotte L Joy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Putting Djenné on the Map

CHAPTER 1

Architecture and the “Creation” of Djenné in the West

Narrative about Africa is always a pretext for a comment about something else, some other place, some other people. More precisely expressed, Africa is the mediation that enables the West to accede to its own subconscious and give public account of its subjectivity (Mbembe, 2001: 3).

The historic encounter between Europe and West Africa has always been a two-way process, albeit one with a heavy power imbalance (Probst & Spittler, 2004). To understand current relationships between institutions and nation-states, such as that between UNESCO and Mali, one must document the historical precedents of such relationships: the series of past encounters that have cast agents into defined roles, some of which are very hard to move beyond.

Over the years, Europe apprehended Djenné in different ways. At first it did so through travel writing and exhibitions, part of broader imaginings about the enchantment of Africa (Hall, 2005; Leiris, 1934; Phillips & Steiner, 1999). The interest in its vernacular architecture grew from the time of the arrival in Europe of early photographs, postcards and colonial exhibitions (Gardi, 1994; Gardi et al., 1995; Morton, 2000; Prussin, 1986). These glimpses gave the impression of Djenné as a distant place, with winding streets and compact architecture. Today Djenné remains “enchanting,” because it promises to be so different from people’s places of origin (Hudgens & Trillo, 1999). The way in which Djenné (and its sister town of Timbuktu) has been represented by the West has to a large part been influenced by both the intellectual climate in Europe and the aims of Empire at the time.

At the end of the 18th and turn of the 19th centuries, the influential American anthropologist Lewis Henry Morgan and British anthropologist Edward Tylor postulated that culture, like nature, was subject to the power of evolution. Heavily influenced by Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859), Morgan argued that mankind used experimental knowledge to work its way up from savagery through barbarism to civilisation. Breaking down each stage, he includes “House Life and Architecture” as one of the milestones of civilisation:

house architecture, which connects itself with the form of the family and the plan of domestic life, affords a tolerably complete illustration of progress from savagery to civilization. Its growth can be traced from the hut of the savage through the communal houses of the barbarians to the house of the single family of civilized nations, with all the successive links by which one extreme is connected to the other. (Morgan, 1877, reprinted in McGee & Warms, 2004: 58)

Morgan put a strong emphasis on technological progress and the ownership of private property as markers of cultural progress. In common with Morgan, Tylor (1871) believed in the psychic unity of all of mankind, so that cultural sophistication was a continuum based on knowledge and education, with “primitive” societies representing the childhood of mankind. Architectural and technological sophistication became a key materialisation of this theory. These themes were later taken up and refuted by African intellectuals (for example, Mbembe, 2001). There remains, however, a complex interaction between the West’s perception of architectural sophistication and its correlation with social validation. As Mbembe states, narrative about Africa is almost always about something else: Africa is defined in opposition to the West, as, for example, by lacking the architectural sophistication of the West and therefore not being “fully human” (Mbembe, 2001: 2). However, as attitudes in the West are changed by fears of climate change and a desire for a more harmonious relationship with the natural environment, mud-brick architecture in Africa is coming to represent something new yet again: the promise of a sustainable future through low-carbon-impact technologies.1 This promise responds to Western concerns about the preservation of cultural and natural heritage. The relationship between Europe and Africa is therefore in a state of constant dynamic evolution.

Early Explorers

The “discovery” of West Africa by Europeans began with a number of amateur enthusiasts, spurred on by legendary tales of African cities of gold and unanswered questions about the geography of the continent. The Scottish explorer Mungo Park, encouraged by the British Association for Promoting the Discovery of the Interior Parts of Africa (the African Association), set off in 1795 to find the course of the River Niger (Park, 2002). His predecessor, Daniel Houghton, had died in the Sahara desert—early European expeditions to West Africa were poorly funded and inadequately prepared. Despite suffering from severe ill health, Park managed to reach the river Niger in 1796 at Ségou (the first known European to do so) and, having been assumed dead, triumphantly returned to Scotland in 1797.

Park had failed in his aim of reaching the legendary city of Timbuktu and managed only to follow the river Niger as far as Silla, therefore falling short of both Djenné and Timbuktu. In 1805 he once again set off on an expedition to the Niger, this time as the head of a Government expedition. Of the forty Europeans accompanying him, only a handful lived to reach the Niger, and they all gradually succumbed to fever and dysentery. Park and his party regularly turned their guns on assailants, and it is clear from his account that they “killed a great number of men” (ibid: 394). Based on the testimony of one surviving expedition member (a porter), after multiple attacks by hostile parties from the riverbanks, Park lost his life in December 1805 (from Adami Fatoumi’s journal, reprinted in Park, 2002) after sailing past, but never entering, Djenné (recorded as Ginne) and Timbuktu.

The story of Mungo Park’s adventures, and the subsequent narrative of his travels published in 1815, captured the popular imagination in Britain and across Europe. In 1824 the French Geographical Society (Société de Géographie) offered a cash prize of 10,000 francs to the first person to come back alive from Timbuktu. An early contender for the prize was Alexander Gordon Laing (Kryza, 2006), a Scottish Captain in the Royal African Colonial Corps. Also encouraged by the African Association, Laing was the first European to reach Timbuktu in August 1826, but he was murdered shortly after leaving the city in September of the same year.

The first European to return alive from Timbuktu was René Caillié, a Frenchman of humble birth, orphaned while still a young child, who had long dreamed of travelling to Africa (Berque, 1996). In the account of his travels, Caillié explains his motivation: as a child, “People lent me geography books and maps: those [maps] of Africa, where I could only see desert countries or countries labeled ‘unknown,’ excited my attention more than any other” (Caillié, 1996: 42, my translation). In another passage, he states: “The town of Timbuktu became the continual object of all my thoughts, the aim of all my efforts; I resolved to reach it or to die” (Caillié, 1996: 41, my translation).

After a first failed expedition to Senegal in 1818 accompanying British troops who continually came under violent attack, he returned to Senegal in 1824 determined to reach Timbuktu. His innovative approach was to disguise himself as a North African Muslim traveller by first spending a long preparatory time learning Arabic and the customs of Islam in Senegal. After working for a time in Sierra Leone, he finally set off for Timbuktu in 1827, on the pretext that he was an Egyptian trying to regain his homeland. In March 1828, after a prolonged illness and numerous setbacks, he reached Djenné, where he spent two weeks. He finally reached Timbuktu on April 20, 1828.

On his return to France, Caillié was awarded the 10,000 francs prize, and accounts of his travels were published to great acclaim. Perhaps unusually, given his position, Caillié did not attempt to describe Timbuktu in romantic terms and instead painted a picture of a desert town: “Timbuktu, although one of the biggest towns I have seen in Africa, has as its only resource its trade in salt, its land being too barren for agriculture. It is from Djenné that it gets everything that is necessary for its survival: millet, rice, vegetable oil, honey, cotton, Sudanese cloth, manufactured goods, candles, soap, chillies, onions, dried fish, pistachios, etc….” (Caillié, 1996: 2, my translation). Djenné and Timbuktu therefore entered popular French culture as twin towns of the trans-Saharan trade route. Although Timbuktu may not have lived up to the hopes of the enthusiasts of the African Association and the French Geographic Society, its name had forever entered into folklore, linked with adventure and hardship and the quest for unattainable riches.

Caillié’s detailed description of Djenné as a thriving cosmopolitan trade centre has also had a long-term effect on the West’s perception of the town. His careful attention to people’s beliefs and practices, together with the recording of details including prices, hairstyles, and culinary preferences, provides a rich ethnographic account of Djenné seen through the eyes of a Frenchman in 1828.

The motivations behind Park and Caillié’s journeys were both personal and economic. The French and British governments had vested interests in exploring the potential for trade and exploitation of raw materials in West Africa, and an understanding of the geography and political landscape of the territory was essential for planning further incursions. It is clear through their writings that Park and Caillié were very much aware of these concerns and sought to bring back as much information as possible for the advancement of these aims. At the same time, it is hard to adequately stress the hardship, terror, and physical discomfort suffered by both men in their quest for knowledge about the region, and what therefore must have been the depths of their personal motivation.

Park and Caillié’s accounts of their adventures are considered today to be very problematic orientalist constructions (Grosz-Ngaté, 1988; Said, 2003), written within the language and prejudices of the time. They were written upon the travellers’ return and, in the case of Park, with a large amount of input from a second author, Bryan Edwards, the Secretary of the African Association at the time. Caillié’s account was heavily edited and based on scribbled and badly damaged notes that he secretly kept throughout his journey.

It would perhaps be easy to discount these early accounts on the basis of these limitations alone. However, despite their flaws, accounts written by the early explorers in West Africa set a particular tone for Europe’s perception of towns such as Timbuktu and Djenné. The headlines of the travellers’ exploits in Europe were heroic and triumphant, and to this day, travel companies advertising trips to Mali use a language of exploration and adventure in their promotional literature.

The early travel accounts are also important in two other ways. First, as will be shown, the problematic “power to represent” (Grosz-Ngaté, 1988) found in Park’s and Caillié’s writing is not unique to their time and continues to this day, starting with the early colonial writers and moving through the architects, archaeologists, anthropologists, heritage officials, tour guides, and filmmakers who followed. Inescapably, this book is a continuation of this tradition of the outsider looking in, albeit written within a new reflective practice ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Series Editor’s Foreword Critical Perspectives on Cultural Heritage

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I Putting Djenné on the Map

- Part II Life in Djenné

- Appendices

- Notes

- References

- Index

- About the Author