![]()

Part I

Understanding the resource nexus

Setting scenes

![]()

1

The Resource Nexus

Preface and introduction to the Routledge Handbook

Raimund Bleischwitz, Holger Hoff, Catalina Spataru, Ester van der Voet and Stacy D. VanDeveer

Preface

Demand for natural resources has grown rapidly for decades, and is expected to continue growing. These trends lead to repercussions, risks, and threats for humans and ecosystems at different scales. The challenges of sustainable resource management and governance are on numerous agendas, ranging from the G7 and G20 summits to UNEP’s International Resource Panel, World Economic Forum, SDG implementation, and a growing community of international scholars. Research highlights the importance of accounting for the interdependencies of resource use and sustainability goals such as eliminating hunger, mitigating climate change, and expanding energy access. There is a need to understand interdependencies and the feasibility of more integrated approaches.

Debate is often framed in terms of a “nexus” between water, energy, and food (sometimes including other resources).1 The main aim of this handbook is to come to grips with what the nexus2 is about, provide a reference textbook with an overview, and a survey on emerging and cutting-edge research, and application of the concept.

This handbook is edited by five dedicated scholars, drawing on different schools of thought from different continents. Assembling a wide group of more than 50 authors across a host of disciplines and interdisciplinary fields, this volume rests on a thorough review of relevant literature and, in emerging with a distinct and original perspective, it conceptualizes the resource nexus as a heuristic for understanding critical interlinkages between uses of different natural resources for systems of provision such as water, energy, and food. The editors organized a symposium which took place in London in March 2015, debating various aspects of the resource nexus and refining the concept and defining the structure of the handbook. All chapters have been reviewed several times.

Many chapters seek to contribute to realization and implementation of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs, see Chapter 32, as well as Chapters 4, 19, 22, 26, 27, 28, 29), which endeavor to achieve greater opportunities and a better life for the world population as a whole and for our globe’s poorest citizens, in particular while reducing environmental pressures. These goals – especially SDG2 (food), SDG6 (water), SDG7 (energy), SDG12 (sustainable consumption and production), and SDG15 (sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems) – have extensive and enumerable links to natural resource use, underlining the need for integrative approaches. If implemented in ways that overlook critical interlinkages, the SDGs may well risk a further acceleration of natural resource demand and degradation, ensuing numerous knock-on effects on individuals, communities, businesses and societies – and the ecosystems on which all depend.

Similarly, we perceive this nexus handbook to be connected to topics such as resource efficiency, circular economy, and many others (Bleischwitz, Welfens, Zhang 2011) – all grappling with solutions aimed at more sustainable use of natural resources at different levels (micro, meso, and macro).

This handbook enables readers to understand (Part I), measure (Part II), assess and model (Part III), compare political economies (Part IV), learn from applications (Part V), and upscale solutions (Part VI). The handbook’s six parts and 32 chapters are carefully organized around these aims. As a whole, the handbook seeks to combine analytical rigor with attempts to be transformative – i.e. shaping transformations towards sustainability – in realms of research and knowledge-making, as well as practice and implementation.

Introduction

What is the nexus? An integrated approach

In the past, resource governance mostly focused on single resource categories such as water or energy along a supply chain that ran from primary natural resource, through processing, distribution, and final consumption and disposal. Some of these supply chains are global in scope, such as those for oil, while others are more commonly national or local, such as those for coal and water. Graedel and van der Voet (2010) emphasized the need for a more integrative approach, signaling the existing linkages between the different resources. The nexus concept has been formulated and has become widely used in analytical and practitioners communities at least since the Bonn Conference 2011 (Hoff, 2011) and work at the Transatlantic Academy in 2011–2012 (Andrews-Speed et al., 2012), in response to the predominant single-resource “silo” thinking, emphasizing critical interlinkages across resources, particularly synergies and trade-offs, in a more integrated manner.

Authors in this handbook define the resource nexus as a set of context-specific critical interlinkages between two or more natural resources used as inputs into systems providing essential services to humans, such as water, energy, and food.3 While a multitude of possible relationships, resources, and systems can be considered, we outline in this chapter a clearly defined five-node nexus for the systems of water, energy, food, land, and materials that seeks to provide consistency, focus, and adaptability to the respective scope and context of analysis and application. Advantages of this particular scope of a five-node nexus are detailed in the following section, with a focus on making robust choices across different contexts, linking with ecosystem services, and bringing in the dimensions of scale and the socio-economic metabolism.

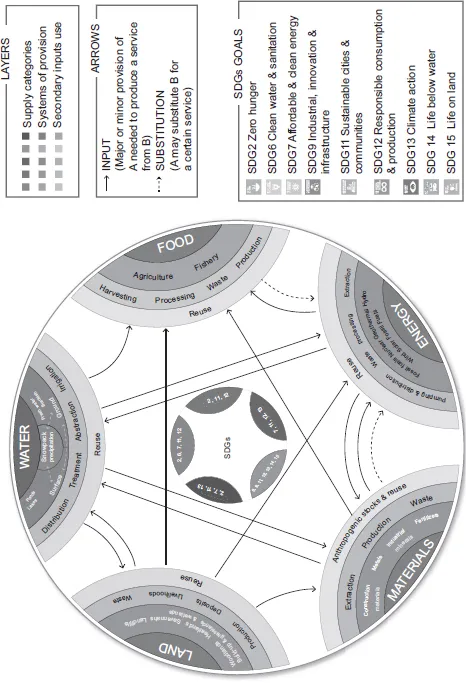

Systems thinking is key. In general terms, natural resources serve as direct or functional inputs for socio-economic systems of provision, either for the production of another input, for general production and consumption purposes, or for the built environment. Figure 1.1 illustrates the main resource interlinkages between five essential resources and how these provide a basis for societies and sustainable development. Looking at those interlinkages, some may be more obvious to many readers than others, such as the bi-directional connections between energy and water. Others become more critical during periods of rapid increase in the use when sticking to typical silo approaches without assessing the availability of core inputs from other resources, such as the materials needed for energy production.

Figure 1.1 also introduces three layers in order to illustrate the value chains from nature to consumers for each resource. The first layer gives categories for the primary production of the respective natural resource; the second layer adds the socio-economic supply systems based on such resources. The third layer adds the dimension of recycling and re-use and inputs from secondary resources – essential for enhanced resource use efficiencies, a circular economy, and a more sustainable use of resources in general. Critical interlinkages may occur between corresponding or different layers, as illustrated by energy needs for pumping water through distribution systems to end-users. We will discuss our proposed categories in the section on the scope of the nexus.

Figure 1.1 The resource nexus

The figure illustrates main interlinkages in a generic manner based on the many existing studies. Certainly more such interlinkages exist, and the figure looks at them from the perspective of resource inputs being transformed and providing essential services for humans. Nexus research should be quite explicit about those layers, their scales, and how critical interlinkages can be identified. As this figure is applied throughout the entire handbook, we seek to demonstrate the usefulness of a nexus approach. Systems thinking, however, suggests research and practitioners should start from a broader nexus understanding but may well focus on certain critical interlinkages across selected layers. Accordingly, the handbook also entails chapters on cases related to water–energy–food in China (23), metals and energy (24), unconventional fuels and the nexus (25), and energy and water in California (31).

The importance of natural resources for development was repeatedly identified at Earth Summits in 1992, 2002, and 2012, and in SDGs such as (renewable) energy (SDG7), (sustainable) food production (SDG2), and sustainable management of water (SDG6). As such, Figure 1.1 also illustrates some of the links between natural resources and relevant SDGs.

The nexus approach stresses the need to generate relevant information about critical interlinkages that enable decision-makers to plan for robust governance and management across resources and spatial scales – consistent with planning frameworks such as national development plans, sustainable development strategies, or energy or agricultural transitions. Planners ‘on the ground’ are probably a key target group of a nexus approach. While many previous nexus studies are limited to one particular scale, e.g. the national or regional levels, analyzing interlinkages helps to connect across scales, from small, local places to international trade and global cycles (Hoff, 2017, see also Chapter 3 and Chapter 28 on urban governance). In the future we expect more findings connecting to global scales such as the planetary boundaries approach (Steffen et al., 2015) which emphasizes interlinkages between different large-scale environmental processes. Likewise, the nexus approach should enable more consistency as critical interlinkages become part of mission-oriented strategies such as resource efficiency or a circular economy (Ellen MacArthur Foundation and McKinsey, 2014).

Building on diverse strands of expertise, a nexus approach generates improved knowledge of cross-resource needs and impacts for decision-making and management. As Wichelns (2017) points out, such multifunctional management approaches have a long tradition of being embedded in UN principles and legal frameworks, especially in forestry management and the Dublin principles on water management. Yet, integrated approaches are still an exception rather than the rule. If practitioners or scholars in one sector attempt to reach out to others, feedback from other sectors or policy implementation remains weak in integrated concepts such as integrated water resource management (IWRM). The nexus approach acknowledges that integration adds complexity and hence is difficult to implement, and that addressing all interlinkages is impossible. Yet it rests on the assumptions that (i) identification and assessment of critical interlinkages is essential, and (ii) managing and governing such interlinkages is a key to achieve the SDGs, clearly superior to managing single resources in silos (Le Blanc, 2015; UNEP, 2015). The nexus framework enables actors to identify risks of overuse, to exploit synergies (ancillary benefits, co-benefits, more sustainable investments, cost reduction in joint policy implementation, etc.), and to manage trade-offs and contradictions.

Thus, a nexus approach seeks a more efficient resource management that addresses multiple targets in a more integrated manner. This is why the solution-oriented concepts of resource efficiency and a circular economy are closely linked with the nexus; Part VI of this handbook is devoted to such solutions. Note that such integrated approaches could also be applied when one resource (e.g. a forest) is governed for multiple and often conflicting goals, such as protecting biodiversity and water resources, community livelihoods, and timber production.

The scope of the nexus

Little agreement exists in the literature as to what natural resources are included in the nexus. The most widely acknowledged nexus approach covers water–energy–food (WEF) (Hoff 2011; Bazilian et al., 2011; Lawford et al., 2013; Green et al., 2016). Other studies and some chapters of this handbook focus on:

- The water–energy nexus (Ackerman and Fisher, 2013; Howells and Rogner, 2014; Talati et al., 2016; see also Chapters 23, 25, and 31) inspired by the huge amounts of energy needed for water pumping or desalination and vice versa: the large amount of water needed in the energy sector, as illustrated by the impact a drought might have on electricity production;

- Water–energy–land (European Commission, 2012; Ringler et al., 2013; Senger and Spataru, 2015; Sharmina et al., 2016; Obersteiner et al., 2016; see also Chapters 16, 22 and 26) all pointing to the manifold ecosystem services provided by land and the intersections with water, biomass, biodiversity, and energy;

- Water–energy–mineral fertilizer (Mo and Zhang, 2013; see also Chapter 26) highlights the potential depletion of non-renewable natural resources (minerals), their relevance for food security, their complex supply chains with recycling and recovery opportunities from e.g. wastewater or agricultural residues, and the potential environmental risks from accumulation of these minerals via eutrophication;

- Water–energy–minerals (Giurco et al., 2014; Kleijn et al., 2011; see also Chapters 18, 19, 21, 24) as illustrated by the increasing intensity of water and energy use in mineral extraction processes with declining ore grades. The reverse interlinkage is an increasing demand for minerals including metals for energy infrastructures, renewable energy such as photovoltaics or wind power, batteries, and unconventional fuels.

More policy-oriented studies published by Chatham House (Lee et al., 2012) and authors at the Transatlantic Academy (Andrews-Speed et al., 2012, 2015) share a wider recognition of natural resources as manifold inputs into socio-economic processes and metabolism in line with Figure 1.1. A similar approach is taken in the analysis by the McKinsey Global Institute (Dobbs et al., 2011), which focuses on opportunities of a ‘resource revolution’ for steel and related industrial sectors.

In order to provide a meaningful scope, this handbook proposes a five-node nexus to address:

- Water

- Energy

- Food

- Land

- Materials

While food – like water and energy – has been an essential category of the nexus debate from the very beginning, one may discuss consistency by pointing at the need to produce food rather than seeing it as a primary resource. Yet, our approach of including food points at its relevance as a system of provision (SDG2) with inputs needed from all other resources, manifold critical interlinkages, and resource-intensive value chains at all layers. Indeed, a life cycle approach is essential for systems thinking and for all categories of the nexus.

Inclusion of land in a resource nexus approach is necessary because of its many critical environmental functions, and as a prerequisite to relevant provisioning services and development. Figure 1.1 illustrates land as an input into all other categories, and its critical interlinkages with water.

This nexus handbook further includes materials in the resource nexus for at least four reasons. First, non-energy abiotic resources are essential for housing and shelter and account for about 50% of natural resource use in most industrialized countries measured in physical units according to material flow analysis (see Bringezu and Bleischwitz, 2009; Wiedmann et al., 2013). Second, base metals, critical minerals, and construction minerals have significant implications for energy production, storage, and distribution (SDG7); water provision and re-use (SDG6); and urbanization (SDGs9+11). Mineral fertilizers are also critical inputs for food production (SDG2). Third, costs associated with purchasing and processing materials in manufacturing industries are significant and have been estimated in the order of 40% of gross production costs throughout the 2000s (Wilting and Hanemaaijer, 2014). Lastly, base metals and nutrients cause particularly significant environmental impacts, including land and water resource degradation and GHG emissions (Hertwich et al., 2010). Nevertheless, int...