- 243 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Memorial sites, sites of "dark tourism," are vernacular spaces that are continuously negotiated, constructed, and reconstructed into meaningful places. Using the locale of the 9/11 tragedy, Joy Sather-Wagstaff explores the constructive role played by tourists in understanding social, political, and emotional impacts of a violent event that has ramifications far beyond the local population. Through in-depth interviews, photographs, graffiti, even souvenirs, she compares the 9/11 memorial with other hurtful sites—the Oklahoma City National Memorial, Vietnam Veteran's Memorial, and others—to show how tourists construct and disperse knowledge through performative activities, which make painful places salient and meaningful both individually and collectively.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Heritage That Hurts by Joy Sather-Wagstaff in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

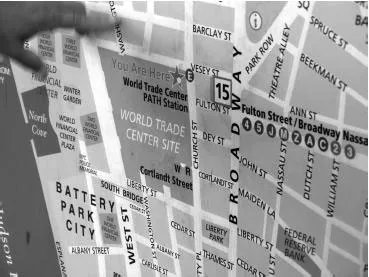

Figure 1.1 Manhattan map at the World Trade Center visitor’s kiosk (© Joy Sather-Wagstaff 2004)

“YOU ARE HERE”: CONSTRUCTING A HERITAGE THAT HURTS

Tragedy—human death and injury, the physical destruction of buildings and landscapes, and the psychological and social dissonance that results—is processually transformed into memory and historicity through the social production, construction, performance, and consumption of commemorative sites for what John Schofield, William Johnson, and Colleen Beck describe as “a heritage that hurts” (2002:1).1 Commemorative sites are not automatically sacred or otherwise historically important simply because a disastrous event occurred; they are spaces that are continuously negotiated, constructed, and reconstructed into meaningful places through ongoing human action. Although usually understood as static places of “official” cultural expressions of history and memory, particularly when fully formalized with museums, monuments, and memorial landscapes, these sites both generate and are informed by what John Bodnar defines as “public” and “vernacular” history and memory through polysensory human engagement with the places themselves (1992:75).

Public memory and history “emerge from the intersection between official [dogmatic, homogenous, and authorized] and vernacular [multiple, ambiguous, local, and heterogeneous] cultural expressions” (Bodnar 1992:13). Public memory also mediates between dominant, official (and usually national) narratives and local or individual narratives, and it is also a means of accepting, resisting, informing, or even significantly altering these official histories and memory. It is largely through tourism that commemorative and other historical sites act as places where these official, public, and vernacular histories and memories intersect and act in dialog. Visiting sites of tragedy and death is not only a way for people to question the “mythic underpinnings of society” (Kugelmass 1994:178); in the process people make the sites historically salient in official, public, and vernacular memory across communities of belonging, both imagined (Anderson 1991) and lived in the everyday.

The events of September 11, 2001, continue to endure in cultural memory for many as an unexpected, violent rupture in everyday life that forcefully marked the transition from the 20th to the 21st century. The events and aftermath of that day are the focus of my study, specifically as they are represented in the commemorative site-in-process that has been and will remain the shifting World Trade Center (WTC) landscape until the formal memorial landscape and museum are completed. In my research I focused on the on- and off-site experiences and memories of a broadly dispersed public as represented by tourists who visited New York City during 2002–2009 and their role in the making of the WTC commemorative site. To focus on tourists enables an understanding of how violent events of scale are culturally mediated through time and space, the generative, everyday relationships between collective and individual agents in the production of historical consciousness, and the socially constructive roles that visual and material culture and embodied experience play for memory-making in an age of mass production and consumption.

This ethnography goes a bit of the way to meeting anthropology’s ongoing challenge to “illuminate, inform and expand the possibilities of personal, social and political responses to 9/11” (Clarke 2004:10), representing only a very minute fraction of the many narratives of 9/11. These stories are continually unfolding histories-in-process, and although the events of and responses to 9/11 are perhaps the most documented of any disaster of scale in human history to date, the struggle and challenge to make sense of them continue. As a scholar in a largely interpretive social science subdiscipline, I join others across disciplines in a commitment to generate a much-needed “critical, humane discourse that creates sacred and spiritual spaces for persons and their moral communities, spaces where people can express and give meaning to the tragedy [of 9/11] and its aftermath … connecting the personal, the political, and the cultural” (Denzin and Lincoln 2003:xv). A wide range of valuable public and scholarly projects on 9/11 have already been undertaken. Through this book I add more stories, voices, and perspectives—both mine and my participants’—to this growing body of works.

This book’s contribution is built on the fact that (to my knowledge), no scholars have looked specifically at tourists as a primary, relevant population for study that focuses on 9/11 commemorative sites. In general, when tourists to the WTC site are mentioned in the media and by scholars, they are usually disparaged and criticized, framed as profaning the “sacred site” with their touristic activities. Yet tourists not only are directly and indirectly providing economic support for commemorative sites worldwide, they also are the population that geographically disperses knowledge of these sites through the narrative, performative, and visual culture of travel once off-site, post-visit. In the case of 9/11 they also represent what sociologist Kai Erikson identifies as the “hinterland” population of the United States and beyond, one that has been far less studied than persons in and around New York City yet who nonetheless “feel that they were witnesses to, victims of, even actors in” the event (2005:354). I therefore consider tourism to be a significant part of the cultural terrain through which tragic events past and present are apprehended, comprehended, and commemorated.

This book presents a deeper understanding of the social, political, and emotional effects and consequences of violent events that reverberate far beyond the physical sites where they occurred and in the process reveal the constructive roles that tourists play in making the diverse and often contested meanings accorded to historical commemorative sites. Although my primary focus was on 9/11 sites, my study is contextualized within a range of contemporary commemorative sites that have been formalized or, like the WTC site, are still in process. The Oklahoma City National Memorial plays a significant comparative role as a formalized site, as does the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. Both sites have greatly influenced the cultural templates for the formal WTC memorial landscape and museum, other 9/11 memorial landscapes, and the various commemorative practices performed by locals and tourists at the WTC and other sites of disaster, tragedy, and death. Like the WTC, both sites are also tourist destinations, and the Oklahoma City site is one that depends heavily on tourism for its existence, both economically and as a site that continues to develop its historical saliency as one of the most devastating occurrences of terrorism on U.S. soil.

“WE’VE BEEN ATTACKED …”

On the morning of September 11, 2001, millions of people saw or heard what transpired as it happened. Many in Manhattan and the surrounding areas witnessed the events at the WTC firsthand—some never survived to tell us what they saw. Those of us at a geographical distance from the disastrous events occurring in New York, Pennsylvania, and Washington, D.C. were second-hand witnesses, watching in shock as the events unfolded on television and were replayed over and over on nonstop news broadcasts. American Airlines Flight 11 from Boston, the first of four airplanes highjacked by members of Al-Qaeda, an Islamic extremist organization, crashed into the north tower of the WTC at 8:45 A.M. Eastern Standard Time. Eighteen minutes later, United Airlines Flight 175, also from Boston, crashed into the south tower. By 9:21, with both towers burning, flames and smoke visible from miles around, all New York and New Jersey airports had been shut down and all bridges and tunnels in the area closed to further ground traffic.

Twenty minutes later, all United States airports’ flight operations were stopped and all inbound trans-Atlantic flights rerouted to Canada. American Airlines Flight 77 crashed into the Pentagon at 9:43—it originated at Washington, D.C.’s Dulles International Airport only a few miles away—and the White House was immediately evacuated. At 10:05 millions watched in stunned horror as the south tower of the WTC collapsed. Five minutes later, United Airlines Flight 93 from Newark, New Jersey, crashed near rural Shanksville in Somerset County, Pennsylvania. The north tower of the WTC collapsed at 10:28. It was noon before American Airlines and United Airlines confirmed the loss of all four of the highjacked flights. At 5:20 Building 7 of the WTC collapsed after sustained fires and debris from the fall of the north tower had weakened the structure.

In all, four of the seven WTC buildings (1, 2, 3, and 7) were nearly or completely destroyed in a matter of hours, and the remaining three (4, 5, and 6) were so badly damaged that they were later demolished.2 Thousands of local and nonlocal professional rescue workers and volunteers worked feverishly at the WTC site through September in the hopes of finding survivors, yet very few were found. Fires at the site burned until December, and clearing the debris took over nine months as recovery workers checked and rechecked for victims’ remains amid tons of steel and concrete. On May 30, 2002, debris recovery was officially completed, and a somber ceremony including the removal of the last steel column marked this occasion. During 2006 and 2007, as rebuilding construction increased, human remains were found in several underground locations and atop nearby buildings, spurring yet more new searches of the area for recoverable and possibly identifiable remains. As of May 2007, 2,750 death certificates had been issued including those for victims who died on 9/11 at the WTC as well as rescue and recovery workers who died from conditions resulting from their work at the site.

Since September 2001 the repercussions of the 9/11 attacks have affected millions on a global scale, resulting in even more victims of violence to be memorialized. The “War on Terrorism” began in earnest, starting with the almost immediate invasion of Afghanistan by the United States in October 2001. The second war in Iraq began in March 2003—as of 2010, the death toll for coalition troops is almost 5,000, and civilian deaths are estimated to be in the hundreds of thousands. Other terrorist attacks by Islamic extremists have since occurred outside the United States, killing a total of 452 persons and injuring over 3,000 in the March 11, 2004, train bombings in Madrid; the July 7, 2005, bombing of trains and a bus in London; and the July 11, 2006, bombing of trains in Mumbai. Commemorative sites have been established in Madrid, London, and at the Pentagon, with the Shanksville 9/11 memorial under construction. At the WTC site proper, a complex combination of politics, economics, shifting plans for rebuilding, contests over commemoration, and reconstruction have been in process since the attacks.

Informal, “makeshift” memorials emerged in public spaces around New York City, and talk of a permanent memorial and replacing the lost buildings began immediately following the attacks. Owing to the complexity of the WTC land ownership, building ownership, existing lease contracts, and the need for both a memorial and office buildings, Governor George Pataki formed the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation (LMDC) in December 2001. The LMDC, overseen by New York State’s economic development agency, has been overseeing the planning process, choosing Daniel Libeskind’s Memory Foundations in 2003 as the WTC site’s master rebuilding plan. Libeskind’s plan included five office towers, a transit hub, retail space, a cultural center, a memorial museum, and a memorial landscape. In January 2004 Michael Arad and Peter Walker’s Reflecting Absence design was chosen for the memorial landscape to be included in the master plan.3 Processes of both planning and rebuilding have been extremely controversial, generating a number of detailed works (for example, Beauregard 2004; Rosenthal 2004; Sorkin 2003; Sturken 2004; Young 2006) outlining and critically evaluating these processes, tensions, and controversies.

CURRENT STATE OF THE WTC SITE

At the time of this writing, the National September 11 Memorial is slated for completion in September 2011, the 10-year anniversary of the attacks. The reconstruction of the area has been fraught with controversy, competing claims for space, the dislocation of businesses and people, and skyrocketing costs.4 The site is a place where thousands of people died on 9/11, effectively becoming a graveyard endowed with a high level of contested symbolism. Construction on replacements for the major buildings that were destroyed has seemed to move at an interminably slow pace, slowed even further by constant changes in designs and alterations in building locations. Although not a part of Daniel Libeskind’s Memory Foundations design for the WTC rebuilding, the first replacement building to be completed was 7 WTC, begun in 2002 and finished in 2006 at a cost of 700 million dollars. Indeed, much of Libeskind’s design has been changed, including the redesign of One World Trade Center, more commonly known as Freedom Tower, by David Childs.

The commemorative cornerstone5 for Freedom Tower was laid on July 4, 2004, only to be removed on June 22, 2006. When the original design and location were heavily altered to address security issues, the cornerstone no longer fell within the tower’s planned footprint, and it was removed with far less fanfare than occurred during its installation and dedication. In December 2006 installation of the foundation beams for Freedom Tower began with two of the columns ceremonially signed by victims’ family members and Libeskind. Ground was officially broken in March 2006 for Arad and Walker’s commemorative landscape and for the National September 11 Memorial Museum, designed by the firm Snøhetta. While research for this book was being done, construction waxed and waned across the site; informal and formal (both temporary and permanent) memorial landscape elements were established at and close to the site, resulting in shifting loci for commemoration across parts of the site’s perimeter and surrounding area over the years.

During 2001, after access to the area was available to the public, and for much of 2002, a locus for commemorative activity was at St. Paul’s chapel, located east of the WTC site but far enough from the debris-recovery process during this time to be accessible along Broadway Street. In December 2001, at the WTC site itself, a public viewing platform surrounded by plywood walls opened; this became a second locus for memorialization, as the plywood walls were quickly covered with commemorative assemblages of memorial posters, flowers, candles, messages, and other commemorative offerings. The platform was closed in the summer of 2002, and in the fall a memorial fence was erected along the west side of Church Street, overlooking what was sometimes called “The Pit” (Figure 1.2). This fence, officially called a “viewing wall” by the LMDC (evoking “The Wall,” the common shorthand name for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C.) opened to victims’ family members and other invited guests on September 11, 2001, and to the public on September 15, 2002. The wall lined the WTC site along Church Street and part of Liberty Street and was embellished with large plaques containing listings of victims’ names and a photographic and textual history of the WTC and the attacks of 9/11 in New York, Washington, D.C., and Pennsylvania. In 2004 the wall contents included the rebuilding plans for the site and over time contained other temporary visual installations. The temporary WTC Port Authority Trans-Hudson (PATH) transit station, a main hub for commuters from New Jersey, reopened in 2003, and access to the station has moved multiple times as construction has progressed. In 2007 the area outside the PATH station area became one of the primary loci for commemorative activities, since construction limited pedestrian access on the remainder of the site along Church Street. The entry has now been moved again, because the station is scheduled to be replaced with a much larger transit hub designed by architect Santiago Calatrava.

The Tribute Center, an interim memorial museum, opened in September 2006 on Liberty Street along the southeast edge of the site. The Tribute Center contains a memorial exhibit and offers guided tours of the WTC site. Victims’ family members work as many of the guides. And beyond the site proper, Fritz Koenig’s sculpture “The Sphere,” recovered from the WTC debris, was installed in Battery Park on March 11, 2002 (the six-month a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Chapter 2 Memory, Space/Place, Tourism: Paradigms and Problems

- Chapter 3 Unpacking “Dark” Tourism

- Chapter 4 Consumption, Meaning, Commemoration

- Chapter 5 Marking Memorial Spaces, Making Dialogic Memoryscapes

- Chapter 6 The Material Culture of Violence and Commemoration in Public Display

- Chapter 7 The Social Life of Things: Material and Visual Culture of Travel and Personal Historiography

- Chapter 8 Conclusion: The Contest of Meaning and Cultures of Commemoration

- Appendix

- Notes

- References

- Index

- About the Author