eBook - ePub

Trust in Virtual Teams

Organization, Strategies and Assurance for Successful Projects

- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

As projects become more complex and the project teams are more geographically and culturally dispersed, so strong, trusting relationships come to the fore. Trust provides the security that enables project teams to work together effectively, even when they face project-threatening problems and challenges. Because today's team members work virtually as much by choice as by geographic necessity, business leaders must understand how team relationships such as trust, cross-divisional projects, and how offshore team participation are all positively motivated by a solid quality assurance program. Offering real world solutions, Trust in Virtual Teams provides a clear view of how virtual projects can succeed, and how quality assurance compliments and promotes effective organizational design and project management to build solid trust relationships. Dr Wise combines the latest research in virtual team trust with simple and proven quality methods. He builds upon more than 20 years of experience in quality and project work to guide team managers in creating high performing project teams. Our understanding of the role human factors play in project performance and project resilience continues to grow. As it does, so does our need to address the behaviors and culture that enable good performance. Tom Wise's book is a thoughtful and pragmatic guide to help project teams and managers do just that.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Trust in Virtual Teams by Thomas P. Wise in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Quality Control in Engineering. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Understanding and Building Trust

Introduction

Why are communication and trust once again topping the list of your annual employee survey? Every year executives struggle to determine why their employees don’t trust the company, and why the employee survey consistently says communication is the biggest problem facing employees. Teams are formed each spring to address these very problems, and at the end of the year trust and communication once again top the list. Trust and communication are often one and the same, in the sense that they are mutually interdependent.

An individual’s awareness of trust grows in layers. Beginning in our early years, as our personality starts to form, we develop a sense of what trust means through our experiences. When expectations are met we learn to expect that those same expectations may be met in the future, and as we watch the world around us we build within us a sense of equity, of rightness or fairness. As we experience life as an employee we learn fairness and equity through our perception of company policy and the implementation of those policies, and as we develop as team members and group participants we discover information about our work life and peers.

Each of these layers of experience create our expectations, our values, and the basis on which we trust one another. We carry to the workplace our trustworthiness and an expectation of the trustworthiness of others, as well as an intuitive ability to measure and prescribe trust upon each other, and assess the balance of equity. In a 2003 study Sarker, Valacich, and Sarker described these layers of trust as personality based trust, institutional based trust, and cognitive based trust. Information (or sometimes the lack of it) affects our perception of trust and our judgment of corporate communications.

When we understand trust in the collective form, we can then understand trust as situational to the given conditions. Trust, when we are talking about personality based trust may be dependent upon the individual’s experiences from early childhood regarding the trustworthiness of specific stereotypical descriptions based on role, race, or ethnicity, or given conditions. This can be in part based on one’s personality traits such as suspiciousness regarding a belief in the inherent honesty of society. It is the discovery of information, and the development of effective communication strategies, that makes trust and communication come together to form a solid bond of connectedness that underpins an effective team and company culture (Halgin, 2009). A sense of family, or connectedness, provides for the expectation of a shared future in their membership, lowers the sense of vulnerability in the group, and opens channels for self-disclosure.

When we look at cognitive based trust, we are evaluating information that is discovered regarding the situation or persons involved in a specific situation, or perhaps forming conclusions regarding the trustworthiness of a group. A decision to trust or not trust is consciously evolved based on an analysis of the available information. As team members seek information, the degree to which reliable information can be discovered will hamper or enhance the degree to which team members may conclude that trust is worthy in the situation.

Institutional based trust describes the level of trust that team members may have in the degree to which corporate policies and procedures are fairly and honestly applied across the organization. As team members work in and with organizations and individuals, they will draw conclusions regarding the way in which management implements and manages the processes and policies governing their work and work lives. Perhaps the establishment of a well supported quality assurance function may provide the needed transparency in process reporting regarding adherence practices for institutional rules. The primary focus of Quality Assurance (QA) as an organizational process is the discovery and analysis of information, and the effective packaging and reporting of this information to make it easily discoverable.

When QA is done properly, the focus of the QA program is aligned to the strategic plan, and the tactical goals of specific organizations. The process of QA enables effective discovery of information, makes transparent our expectations on compliance to company policy, and focuses the organization on what is important. Tracking and reporting on how well we are doing against our own policies builds solid institutional level trust, establishes the foundation for cognitive based trust, and capitalizes on our own personality based traits regarding expectations of trustworthiness. It does not do us any good to track and manage our business processes if we fail to share the results of this analysis. We want everyone to know how well we are doing with compliance. Ironically, poor compliance can build trust, just as effectively as good, but it is good compliance that builds strong bonds.

If we are collectively able to trust the information we receive as accurate and fair, then simple reports, auto-generated to tell everyone how well a project is complying with the stated lifecycle, are all that an effective organization requires. These reports can be held in a standard repository that everyone can access for all the projects and can use to get immediate feedback on the health of the business. This type of openness and ease of discovery can provide effective and immediate feedback to all employees as to the equitable implementation of company policies. When done well, it provides quantifiable evidence that we are equally entitled to and share a common set of practices no matter where we sit. Trust is supported by common norms and practices, and while very basic, the practices that define how work gets done are very important.

A key to effective reporting is to ensure the data collected and analyzed are designed to answer the questions that people are asking. All too often QA programs are maligned and eventually abandoned because the program collects data that is easy to collect rather than data that is necessary, and present the data in expensive, hard to maintain charts. Adding to the problem is the often used practice of presenting the data in a location to which many people cannot find, and making the charts hard to identify and locate. Before beginning any QA program, first ask yourself what questions need to be answered. What is the dilemma to be resolved, and what questions must management answer to resolve the dilemma. Next, identify specific research questions that will provide the data to answer the management questions. If the QA program begins with these simple points in mind, the data will be both useful and effective in providing information that is well designed, and will likely support the needs of the organization and the individual team member.

The goal here is to build a clear understanding that the policies and procedures of the organization are equally and fairly applied to all participants. By making public how the lifecycle is managed, and the degree to which participants in the lifecycle are expected to comply with the policies and procedures, all participants are able to gather the information to confirm an even playing field. But what happens if our publicly displayed information shows that the process is broken or that no one is following it?

1 Understanding Trust

Trust grows in layers, beginning in our early years. As our personality develops we develop a sense of what trust means through our experiences with trustworthiness. When expectations are met we learn to expect that those same expectations may be met in the future, and as we watched the world around us we built within us a sense of how it all works; of equity, or fairness. Each of these layers provides the basis on which we trust one another. This holds true for the trust between employees, teams, departments, and organizations. We carry to the work place our trustworthiness and an expectation of the trustworthiness of others, as well as an intuitive ability to measure and prescribe trust upon each other, and assess the balance of equity. In a 2003 study, Sarker et al. described the layers of trust as personality based trust, institutional based trust, and cognitive based trust.

Personality Based Trust

Our personality, I am told, is pretty much set by the time we reach the age of seven. It means that when it comes to personality based trust the company receives the employee’s personality as fully matured, and with limited opportunity for shaping. Personality develops as the result of experiences during the earliest times in our lives. The other kids were always more than willing to tell us who we should trust: don’t trust Jimmy (he’s a liar), and always trust Sara (she’s a friend). Trust in these circles was based on who knows who, and who follows through on their promises, or meets our expectation of trustworthiness. Thus the expectation of trust is pretty much established by the third grade.

As we grow, and our experiences branch out to include school and work, consistent behaviors begin to breed new levels of trust. We can trust in behaviors that are consistent, even when those behaviors are consistently threatening, because the consistency provides a backdrop for trust to develop. As we grew we all knew kids that the other kids and parents would tell us we should stay away from, and which kids we could approach. Kids know they can trust that a bully will always behave like a bully, even when at times they appeared to want to be friends. The bully could always be trusted to be the bully in the end. Thus, for most of us, inconsistent behavior amongst friends is far more confusing and, indeed, threatening, than the consistently threatening behavior of the bully. Our expectations and desire for consistency and strong relationships become key to personality based trust at the corporate level.

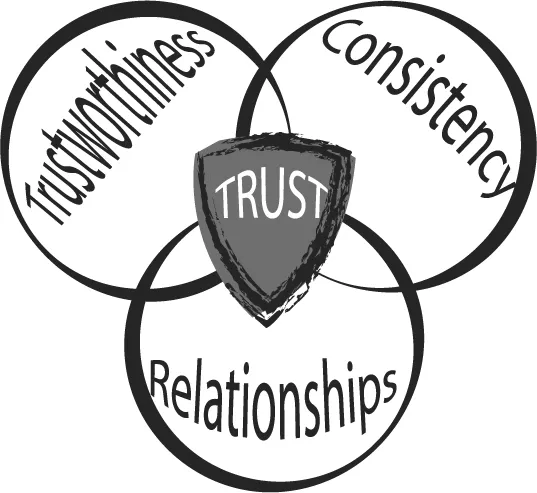

Figure 1.1 Framework of personality based trust

These experiences will often define our expectation of the work place and affect how we see our co-workers, employees, bosses, and team mates. In each of us there lies a propensity to trust, or not, which affects how we perceive the trustworthiness of others. In us we carry the expectations of what is trustworthy, as we also develop a sense of our own trustworthiness. Personality based trust, as Figure 1.1 depicts, can be said to be a juncture of perceived trustworthiness, the consistency with which the person acts as expected, and the relationship with the trusted person. When the three points of trust come together, personality based trust may be prescribed upon the trusted person. At times this may seem odd, but the bully may be trusted; at the very least, trusted to be a bully.

Cognitive Based Trust

We learned to watch out for the bully, and we learned who our friends really are in a pinch. Learning creates an understanding of the world around us. Cognitive trust is a trust that we choose to place in a person, group, or program based on information that we have gleaned from our past. This may include information learned during our years of education and learning; perhaps through experiences we have encountered in similar situations with people or programs. As we take our past learning for use in current or similar situations to decide if trust is a reasonable response to the situations we face, the learning is often enhanced if we have a solid belief that we may also have a future relationship with the individual or group (Mizrachi, Drori & Anspach, 2007). The expectation of future relationships with a good experience have a way of strengthening that relationship, because when we expect that a trusted condition or relationship will remain, it will cause reliance upon that condition or relationship to grow.

As we grow, our experiences in the past become our expectations for the future in terms of situations or behaviors of the people around us, and we don’t need to look further for evidence to decide to trust. Remember the saying, “familiarity breeds contempt?” This may have some truth to it. Familiarity, according to Lewis and Weigert (1985) is a precondition to prescribing or withholding trust. I often remember how, when I was told not to trust another kid, I would wait and watch, wondering what they might do. As I learned more about that person, then I would learn to trust that he or she would act in a certain way, in a given type of situation. As a kid I played a lot of sports. Growing up in a military family in the US the expectation was that all the guys played organized baseball, football, and basketball, depending on the time of the year. Often one of the dads coached the team. The first day of practice we would all gather at the field watching as each of the kids showed up. One at a time each of us would emerge from their car with a parent, and the rest of us would watch, waiting to see who would approach carrying a rucksack filled with sports equipment. As the designated dad-coach showed himself we would keep a close eye watching for some clue as to how to build our expectations for the season.

As the dad-coach would emerge with the rucksack full of equipment the discussion would immediately begin. Questions would fly around the team gathered at the field. Has anyone ever been on his team in the past, someone would immediately ask? We would either hear excited responses from those with good past experiences, or groans and warnings from those with bad past experiences. From the stories, the first set of inputs in everyone’s decision to trust or not to trust was the past experiences from anyone with something to share. Team members would share stories from friends and past team mates about the coach’s reputation for fairness, and coaching style. We would all keep an eye on the coach to see who had joined the entourage as they all emerged from the car. Once again groans and moans or excitement and anticipation would pass among the crowd based on the company that the coach kept. The reputation of those accompanying the coach would have an immediate effect, either positive or negative, on our decisions to trust in our coach. If the coach’s kid was a solid athlete and had a reputation for hard work and fair play, that too would color the thoughts of everyone gathering information regarding the new coach. The next input was the first words from the coach’s mouth, and we all waited and watched as the coach approached the group. Often a coach would shout as they arrived for everyone to stand and begin running laps, letting us know immediately that who we were was not of the first importance. The coach that arrived with a vision for the season, a roster in hand showing that he had an interest in who we were and maybe some idea of what we had done in the past, and perhaps a schedule for the day and the rest of the season, would set a tone of consistency and planning. Each of these inputs provided answers to our information search, and data to our questions regarding the trust relationship.

All of this set in the minds of our team mates whether or not we should keep a wary eye, or trust the coach to take good care of us. School would bring the very same watch and wait attitude from each of us. We gathered in a class room watching for the teacher to arrive as we talked amongst ourselves about who the teacher was, who already knew them, and what our mutual expectations might be regarding timeliness of assignments, rewards, and consequences. In both sports and school we learned from experience whether we could or should trust, and then decided individually if we would choose to trust that the coach or teacher would perform the same in the future. The prescription of trust in the cognitive model works the same in our teams and groups in the work place. Trust is a choice based on data gathered from many sources. Our own experiences with the past behaviors we encounter, the current behavior, and whether or not we believe there may be a future in the relationship. As shown in Figure 1.2, a combination of experience, knowledge, and expectation of the future relationship are combined to aid the choice as to prescribe trust upon the person.

Figure 1.2 Framework of cognitive based trust

Institutional Based Trust

Institutional based trust is somewhat different. As we grow we come into contact with the administration of many different institutions. To keep with the youth sports analogy as my first experience in institutional trust, one of the first things any group seeks to identify is whether everyone is truly equal in the treatment and application of policies and practices. As the team would gather we would watch for clues as to whether the coach’s kid would be treated the same as every other kid on the team. Would the coach’s kid have to work as hard as the rest of us in order to get a starting spot in the game? The team would get an early indicator as practice began, whether or not the coach was going to play favorites based on whether his kid was automatically assigned one of the highly coveted positions on the team. If the coach’s kid began practices as the starting running back, or perhaps the lead pitcher, without having to compete for the spot the same as the rest of the team, it was a clear indicator that we would have to compete to be his friend rather than the better athlete.

As kids do, the team would begin working to figure out how hard we would have to work, and what type of goofing around would be tolerated. Practices would always begin with calisthenics. As the warm up began, team members would immediately be watching to see if the kids who slacked off during the exercise would be chastised for their weak participation. If they were ignored, then of course those with a lesser level of motivation would begin to slack off to bring their performance down to the least level of acceptable performance. All of the team members watched as the coach interacted with the players, assigned roles, and doled out chastisement and punishment. If weak performance or effort was not addressed or perhaps even rewarded, or perhaps rules were eased to aid favorite performers while at the same time strong effort was ignored, attitudes regarding fair treatment from the leaders would be adjusted.

Over time everyone would learn what was expected of us, and what we could expect from the dad-coach. The reaction to institutional equity, or fairness, is the same in the work place as it was in our experience on the childhood practice field. We make our decision regarding the trustworthiness of an organization based on...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- About the Author

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- Part I Understanding and Building Trust

- Introduction

- Part II Virtual Team Working

- Introduction

- Part III Quality Assurance, Trust and the Virtual Team

- Introduction

- Bibliography

- Index