- 269 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Ancient Perspectives on Egypt

About this book

The allure of Egypt is not exclusive to the modern world. Egypt also held a fascination and attraction for people of the past. In this book, academics from a wide range of disciplines assess the significance of Egypt within the settings of its past. The chronological span is from later prehistory, through to the earliest literate eras of interaction with Mesopotamia and the Levant, the Aegean, Greece and Rome. Ancient Perspectives on Egypt includes both archaeological and documented evidence, which ranges from the earliest writing attested in Egypt and Mesopotamia in the late fourth millennium BC, to graffiti from Abydos that demonstrate pilgrimages from all over the Mediterranean world, to the views of Roman poets on the nature of Egypt. This book presents, for the first time in a single volume, a multi-faceted but coherent collection of images of Egypt from, and of, the past.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION: THE WORLDS OF ANCIENT EGYPT - ASPECTS, SOURCES, INTERACTIONS

Through the millennia of its history, Ancient Egypt was viewed from a variety of perspectives by the peoples and states with whom it came into contact. And any given state or people could itself experience an almost limitless range of perspectives on Egypt through time, and also through its social strata, as its relationships with Egypt evolved. In this book we present a sample of those perspectives on Egypt from the ancient past, in order that we may appreciate as fully as possible the cultural, social and political contexts within which Egypt was situated. Broadly speaking, the chapters make use of two major categories of primary source, occasionally both: archaeology and written texts. A chronological dividing line between the two types of source occurs at roughly 1500 BC, so that chapters dealing with pre-1500 BC are essentially, but not exclusively, non-textual archaeological, while those dealing with periods from 1500 BC onwards rely more intensively on written sources. Any such dichotomy is at the same time a reflection of research choices leading to apparently differing availability of the sources, part of a trend whereby archaeologists have expended much of their efforts on earlier periods, electing not to invest energies in the excavation of later settlement sites, such as those of the Roman period, where rich textual sources are present.

The potential for historical archaeology in Egypt has yet to be fully realized (Funari et al. 1999). There exists great scope for the generation and application of approaches that tightly combine historical and archaeological theories and methods. The kinds of statements and interpretations that can be generated on the basis of the patchy and complex archaeological evidence are very different from, but often complementary to, those based on written sources, and it is important to ensure that interpretations based on one type of source are not judged by the criteria applied to another.

For the centuries after 800 BC, there is written evidence that allows different and sometimes ‘closer’ perspectives on Egypt. Authors from Greece and Rome reflected on Egypt and wrote down what impressed or appalled them. Their legacy has influenced the image of Egypt in ways that are different from the picture deriving from the archaeological sources alone. O’Connor (2003: 160) makes the point that 1000 BC marks a major change in the status of Ancient Egypt, with increasing dominance in subsequent centuries by external powers, including Nubians, Assyrians, Persians, Macedonians and Romans. The fact of this dominance from outside opens up a range of sources for historians and archaeologists, many found within Egypt, that can be exploited in explorations of the nature of encounters with Egypt, and that is largely the approach employed by the authors in the second half of this volume.

In this opening chapter we explore some broad issues relating to the position of Ancient Egypt within its cultural and social worlds. In keeping with the structure of the book, the first part considers principally archaeological issues relating to ancient perspectives on Egypt, while more textual and historical issues are the focus of the second part.

Archaeological (and textual) perspectives on Ancient Egypt

The perspectives discussed throughout this book, and indeed the book’s title itself, are presented as ancient perspectives on Egypt. First and foremost, however, they are not ancient perspectives at all, but rather modern constructed archaeological and historical perspectives on how Egypt might have been viewed by a selection of its contemporaries. They are perspectives refracted through the lens of the evidence, and above all through the lens of how archaeologists and historians decide to recover, construct and examine that evidence. In this light, it becomes important to establish the nature of the lens itself, to determine how it is constructed, how powerful it is, what resolution of detail it might afford, and what distortions it might generate, as the past is examined through the looking glass. We need to consider how archaeology has approached the past of Egypt, and what perspectives it has generated, permitted and excluded through time.

The birth of Egyptian archaeology is conventionally ascribed to the Napoleonic expedition of 1798–1802 (see several chapters in Jeffreys 2003a). The discovery of the Rosetta Stone and subsequent decipherment of the Egyptian hieroglyphic script ensured that from its inception Egyptology was biased towards documentary sources. The divide between those who read texts and those who conduct archaeological investigations still characterizes Egyptology today, although there are increasingly bold attempts to transcend this artificial divide. Early Egyptology, like its sister disciplines across south-west Asia and much of the modern world, involved the unsystematic looting of rich archaeological sites, especially temples and tombs, with the aim of recovering spectacular objects and written texts that could adorn the museums of western Europe. A walk through the galleries of the British Museum in London, the Louvre Museum in Paris or the Berlin Aegyptisches Museum immediately gives some idea of the sorts of objects sought and obtained during the decades of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Weeks (1997: 68) has nicely caught the atmosphere of those pioneering, destructive expeditions:

It was an exciting time: excavators plundered tombs, dynamited temples, committed piracy, and shot their competitors in order to assemble great collections.

At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, developments in the archaeology of Egypt were largely the result of the innovative work of Flinders Petrie, whose controlled excavations of cemetery and settlement sites were coupled with highly detailed analysis of excavated artefacts, especially pottery. Petrie’s excavation and analysis by ceramic seriation of hundreds of graves from the predynastic Naqada period established a basic chronology for the fourth millennium BC that overall holds good to this day (Midant-Reynes 2000). An associated perspective that no longer finds adherents, by contrast, was his interpretation that the Naqada tombs represented evidence for a “New Race” or “Dynastic Race” of Asiatic conquerors who brought with them from outside Egypt the notion of pharaonic statehood.

Alongside Petrie’s innovative and careful work, the first half of the 20th century saw a continuation of poorly executed and badly recorded explorations of tombs and temples, conducted within the 19th century paradigm of collecting for European museums. The development of contextual stratigraphic excavation, already well developed in Mesopotamia by German archaeologists in the first decade of the 20th century, took much longer to appear within Egyptian archaeology, partly as a result of the types of site being excavated. Deeply stratified, multi-period, mud-brick settlements such as Babylon and Assur in Iraq could be meaningfully explored only through the careful application of stratigraphic excavation and recording. While such sites did exist in Egypt, they were not the main target of excavators. A legacy of the early failure to develop contextual stratigraphic excavation in Egypt lingers on in the methodologically unsound practice of excavating in arbitrary spits, still employed on certain field projects in Egypt (Warburton 2000a: 1,734).

Changes in Egyptian archaeology came with the Nubian Salvage Campaign of the 1960s (but see Jeffreys 2003b: 6). An international appeal by Egypt and Unesco for participation in the salvage excavation of sites affected by the Aswan High Dam brought a host of new archaeologists into the country from Europe, North America and elsewhere. Egyptian archaeology was enlivened by the introduction of some new approaches to survey, excavation and analysis, rooted in the intellectual contexts of anthropological and ecological studies. Some of these proponents elected to stay on and run new projects elsewhere in Egypt. Current long-term, problem-oriented projects, such as excavations at Tell el-Amarna (Kemp 1989) and Tell ed-Dab’a (Bietak 1995), epitomize modern approaches.

Many perspectives on Ancient Egypt have undoubtedly been shaped by the particular history of the discipline sketched above. In terms of the excavated and published evidence, upon which interpretations must depend, there is naturally a bias towards tombs, temples and hieroglyphs, particularly in Upper Egypt. Baines (1988: 204) has written that “Egypt appears like an estate focused on the king and his burial, and only marginally like an urban society”. But this appearance is very much the result of Egyptological focus on the elite elements of Egyptian society, the tiny minority of at most a few thousand males who attempted to impose an ideology on their own peoples, an ideology that still holds us in its power through our fascination with its surviving physical manifestations. Most of our recovered sources relate to these small elite groups, while by contrast great swathes of the population have stayed in the dark, silent spaces of history. If we excavated more settlements and private houses, explored more of how lower-class individuals, peasants, women, children, artisans and servants interacted with elite ideologies, as detectable in their material culture, we would undoubtedly find ways to see beyond the appearance of an estate devoted to the pharaoh and his mode of burial. We could at least delineate and amplify the nuances and variations in this conventional image of Egypt through space and time. More recent approaches in Egyptian archaeology, such as Kemp’s excavations of the Workmen’s Village at Tell el-Amarna, have started to provide some substance in this regard, for example by revealing that workers in the village continued to build shrines in their homes to the traditional Egyptian gods despite living in the new capital of Akhenaten whose sun-worship was officially viewed as the state’s exclusive religion (Kemp 1989: 304; Meskell 2002: 11). Here, alongside their superficial allegiance to an elite ideology, as manifest at least in their enforced participation in the physical construction of its monuments, the workers of Amarna were at the same time sustaining and reifying, for us to discover if we look in the right places, their own side of a subtle discourse of power.

In another sense, in the context of Baines’ characterization of Egypt as an estate focused on the pharaoh and his burial, Malek (2000: 111) has pointed out that such a position doubtless was the theoretical or ideological state of affairs but that produce grown, husbanded and offered to the pharaoh, his temples, and his shrines, in practice would be used to feed most of the Egyptian population. In this perspective, Egyptian non-elite elements will have been fully aware of the potential benefits to themselves of at least superficial adherence to an elite ideology, however that allegiance may have been formally expressed through rites and rituals.

The standards of survey and excavation employed, as much as the choice of site or region in which to work, have materially affected the quality and quantity of recovered sources. In connection with the failure of survey to discover evidence of Nubian Nile Valley settlements dating to the Egyptian predynastic and early dynastic periods, Baines has argued that Egyptian oppression of the local population “depressed the inhabitants’ material culture below the archaeological ‘threshold’ for the methods of recovery used up to the 1960s” (Baines 1988: 205). We might then envisage a local Nubian population, perhaps aceramic, transhumant, and living in small dwellings built of perishable materials, whose archaeological traces will be recovered only, if at all, by appropriately nuanced, meticulous methods.

Another, broader issue of Egyptian archaeology that has been shaped by the history of the discipline is the way in which Ancient Egypt has been regarded as culturally sui generis. In the words of Savage (2001: 104):

Egypt was viewed as a peculiar place, whose cultural history was perhaps so unique that it shed little new light on large theoretical issues.

Principally for this reason the study of Ancient Egypt has often stood outside the currents of theoretical developments that have swept through many other branches of the social sciences in recent decades (Champion 2003: 179–184; Jeffreys 2003b). If Egypt was unique, how could it inform on the development of civilization in the rest of the Old World and beyond? A bolder approach in recent years has at last brought Egypt into the arena of grand comparative studies, with results that are highly illuminating both for Ancient Egypt and for its selected comparanda (Baines and Yoffee 1998; Trigger 1993; Wenke 1989).

Finally, the potentials for interdisciplinary, innovative research in the field of Ancient Egypt were well stated almost 15 years ago by Wenke (1989: 132):

If archaeological explanations can ever usefully incorporate social theory, Egypt would seem to be the ideal case to demonstrate this: its techno-environmental determinants are relatively simple, and its early evolution of a written language and elaborate material culture provide us with a long, rich record of ancient ideology. Thus, if current theoretical trends in archaeology continue, Egypt may once again become a primary data base for attempts to explain and understand cultural complexity.

The strengths of the ancient Egyptian archaeological and historical record are being exploited in increasingly holistic and interdisciplinary ways, as exemplified in the pioneering mix of textual, iconographic, archaeological and anthropological approaches employed in Meskell’s (2002) study of private life in New Kingdom Egypt.

Keeping in mind these shifting archaeological perspectives, which constitute the lens through which we look at the past, how might we approach the issue of ancient perspectives on Egypt today? The remainder of this part of the introduction examines selected episodes in the early history of Egypt’s encounters with external peoples and states, attempting to learn something of those encounters and perspectives themselves, while at the same time appreciating how the archaeological lens has shaped our visions.

Contact: earliest encounters and the fourth millennium BC

Apart from palaeolithic encounters with Egypt, certainly as a route for migration from east Africa into the Levant and beyond (Hendrickx and Vermeersch 2000), the first major episode of external contact attested in the archaeological evidence is the adoption or introduction of agricultural practices in the later sixth millennium BC, including the husbanding of sheep and goats, and the raising of wheat and barley, at sites such as Merimda Beni Salama (Hassan 1995). The independent domestication of cattle in the Sahara region, however, indicates a strong local element in the adoption of farming and it may be too simplistic to see the introduction of farming into Egypt in the form of a complete package arriving wholesale from the Levant. In the light of the rather sparse archaeological information pertaining to this important period in Egypt, Wenke’s (1989: 138) suggestion that substantial sedentary communities appear only after the adoption of agriculture, in contrast to the sequence in south-west Asia, may be a reflection of the fact that pre- and proto-neolithic settlements of Lower Egypt have been permanently eroded or, more probably, smothered in Holocene deposits from the Nile. Only carefully targeted future work can hope to address this issue of possible contacts between Egypt and south-west Asia in the Neolithic.

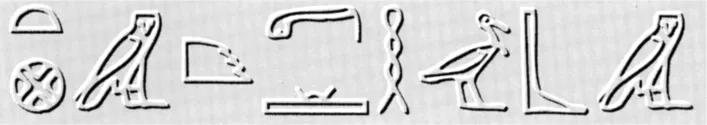

It is with the fourth millennium BC, particularly its latter part, that we are presented with a substantial body of archaeological evidence with which to consider the question of interactions between Egypt and one of its contemporaries, Mesopotamia. For a long time now there has been awareness of evidence for some form of contact between Mesopotamia and Egypt in the later fourth millennium BC (Frankfort 1941; Joffe 2000; Kantor 1992; Largacha 1993; Moorey 1987, 1998; Teissier 1987). The evidence takes the form of limited pottery parallels, a handful of cylinder seals from Egyptian tombs, a few shared artistic motifs, some rather tenuous architectural connections and, most impressively, large quantities of raw materials, such as lapis lazuli, that can only have reached Egypt through Mesopotamia from the Badakhshan region of Afghanistan. At a more structural level, it has also been argued that the idea of writing, but not the specifics, reached Egypt from Mesopotamia (Dalley 1998: 11), and that the notion of a 360-day year comprising 30-day months may also have reached Egypt from the sexagesimal Sumerians of Lower Mesopotamia (Warburton 2000b: 46).

Algaze’s (1993) studies of Mesopotamia in the later fourth millennium, the Late Uruk period, while situating the so-called Uruk expansion within its international context, fail to consider the significance of the Egyptian connection. It seems clear, however, that the evidence for these early contacts is best viewed within the perspective of expanding Mesopotamian horizons through the fourth millennium, coinciding with an independent development of statehood in Upper Egypt. Interpretations of the origins and early development of social complexity in both Egypt and Mesopotamia conventionally lay great stress on the importance of trade, and control over access to raw materials, as stimulants to statehood. The shared cultural features of predynastic Egypt and Mesopotamia, as listed above, can all be viewed as elements of the ‘high culture’ defined by Baines and Yoffee (1998: 235) as “the production and consumption of aesthetic items under the control, and for the benefit, of the inner elite of a civilization, including the ruler and the gods”.

The early development of statehood in Upper Egypt, later spreading to the north, coincided with the maximum diffusion of Mesopotamian influence, itself at least in part economically stimulated, and the assumption by the emerging Egyptian elite of the symbols and seals of a distant elite can be seen as a means, one amongst many, employed by that elite to underpin and expand its legitimacy, by importing and transforming elements of the high culture paraphernalia of a powerful but distant neighbour. The spread of Upper Egyptian complexity to Lower Egypt is likely to have been influenced by the elite’s desire to control access to the raw materials and commodities reaching the Delta from a range of sources. It seems most likely that Mesopotamian influences, however diluted, were reaching Egypt by a sea route from the northern Levant, connected across land to the south Mesopotamian ‘colonies’ on the Euphrates (Mark 1998).

In no case is there evidence for persistent, intimate, face-to-face contact between Uruk Mesopotamians and Late Predynastic Egyptians, and all the raw materials, artefacts, motifs and intellectual notions reaching Egypt from or via Mesopotamia are transmuted into specifically Egyptian forms and contexts before they reach the archaeological record. Pittman’s (1996) study of the Gebel el-Arak knife handle, with its imagery of a typical Uruk priest-king standing between two rearing lions, argues that motifs were adopted not so much for their specific Mesopotamian meanings but rather for the ways in which they operated as vehicles for the conveyance of meaning. Emergent Egyptian elites were thus adopting Mesopotamian high cultural traits, including the notion of writing, the administrative use of seals, high-status artistic motifs, and perhaps time-keeping, at structural and functional levels rather than as random pickings from the...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Series Editor’s Foreword

- Contributors

- List of Figures

- A note on transliteration from ancient Egyptian

- 1 Introduction: the Worlds of Ancient Egypt - Aspects, Sources, Interactions

- 2 South Levantine Encounters with Ancient Egypt at the Beginning of the Third Millennium

- 3 Egyptian Stone Vessels and the Politics of Exchange (2617-1070 BC)

- 4 Reconstructing the Role of Egyptian Culture in the Value Regimes of the Bronze Age Aegean: Stone Vessels and their Social Contexts

- 5 Love and War in the Late Bronze Age: Egypt and Hatti

- 6 Egypt and Mesopotamia in the Late Bronze and Iron Ages

- 7 Finding the Egyptian in Early Greek Art

- 8 Upside Down and Back to Front: Herodotus and the Greek Encounter with Egypt

- 9 Encounters with Ancient Egypt: The Hellenistic Greek Experience

- 10 Pilgrimage in Greco-Roman Egypt: New Perspectives on Graffiti from the Memnonion at Abydos

- 11 Carry-on at Canopus: the Nilotic mosaic from Palestrina and Roman Attitudes to Egypt

- 12 Roman Poets on Egypt

- References

- Index 1: place names

- Index 2: names of people, peoples and deities

- Index 3: topics

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Ancient Perspectives on Egypt by Roger Matthews,Cornelia Roemer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.